Nadège Desgenétez guides us through the alchemic journey of her work in glass, reflecting a deep connectedness to the world beyond the screen.

The TV screen lights up. An array of yellows, greens, pinks and blues … kaleidoscopic colours morphing trees, flowers, water and bodies into one another, all to the sulphury cover of the 60’s pop song This strange effect…

The strange effect is alluring, slick, bodily, trippy, psychedelic.

The TV show is a drama about a well-being retreat set in a large house on the North Coast of New South Wales. I’m watching it as collector friends had thought my sculpture Passage 2 might be best placed in their majestic bathroom, where a large resting tree trunk connects the Australian bush to the minimalist intimacy of their everyday. I think my sculpture was installed in the entrance hall in the end, where it could greet new and returning guests with the intrigue of shifting reflection. Two years later they mentioned a TV drama was going to be shot on location, and that the screenwriters may contact me for the right to film scenes reflected in my work. They chose not to do this, but now, as I watch the screen, I see.

Unfolding in a pristine and dramatic landscape, the fictional mini-series proposes that altered perceptions of reality can allow for an opening of the senses, a receptive alertness to the experiences of others, and their stories, in connection with the natural world.

It is this experience of togetherness and entanglement that inspires my work. In the words of the late philosopher Bruno Latour, “the absence of a common world we can share is driving us crazy” (Latour 2017, p2). In this statement, he refers to the self-destroying character of the dominant anthropocentric—and largely western—worldview. Since the 90s humans have increasingly concentrated their profiting from the earth’s resources towards a dominant elite, while diminishing their accountability towards others, whether humans or non-human living beings, and driving a systematic disavowing of the Terrestrial crisis (p78). Latour advocates for a reinvention of our systems of engagement, inviting us to consider a “[System of engendering] …based on the idea of cultivating attachments, operations that are all the more difficult because animate beings are not limited by frontiers and are constantly overlapping, embedding themselves within one another.” (p83)

My work draws on the ways in which making connects me to the places I dwell in, and people I dwell with, to interrogate ideas of connection, interrelation, and empathy, in a time when experiences of migrations, possessions and futures must be shared. Born and trained in France, I moved to several European countries, the USA and Australia to pursue a career as a glass blower, an educator, and an artist. Whilst privileged, my experience of displacement echoes that of many.

Place for me refers to the location in which my body experiences and hosts the continuum of my life, but also the lifeworld that affects and is affected by me. It is the place in which I stand, the local where land, trees and skies echo the forms, surfaces, and movements of my body. It is also the Terrestrial, the Critical Zone where all animate and inanimate objects share in a complex and uninterrupted becoming.

Nadège Desgenétez, Passage 2 (foreground), in this body here. ANU Drill Hall Gallery 2017. Photography Greg Piper

I am a glass blower. To blow glass, one enters a vexed space, a hot shop, which condenses the problematics of modern times. This is where heavy equipment, largely powered by fossil fuels, and skilled humans, transform raw materials mined from the earth into alluring transparent, hard, fragile glass membranes. These membranes are born from a glob of molten glass, gathered at the end of a hollow metal rod called pipe, from a crucible nestle in the belly of an 1150-degree furnace. The glob is the start. The glob is the precious material in becoming.

- Nadege Desgenetez marvering hot glass, ANU, 2021. Photography Jody Thompson.

- Hot shop, ANU glass workshop, School of Art and Design. Photography Nadege Desgenetez.

When I blow glass, I know I mirror the movements of glass blowers who worked 2000 years ago. This is an anachronistic and elemental pursuit. Yet today is different, as I am a woman in the Anthropocene. Women did not blow glass at the furnace until the late 1960s and until recently they were few who became experts. We know we are at a tipping point. Today, I work with large teams, across many processes (blowing, mirroring, cutting, polishing, sanding, fabricating) to create large mixed-media sculptures.

I can see, feel and also smell the predisposition of the material, as wood, wax, paper, cork and steel come into contact with the outer surface of my gathers.

The process is deeply embodied, present, grounding. Let me try and describe moments in the making of a work. To begin, my body leans into the heat of the furnace. My fingers rotate the pipe to gather the liquid glass. I turn to the metal table (we call it a “marver”) to cool and shape, this time pressing the material at the end of the pipe onto the steel with gentle and even rotations. My lips meet the mouthpiece of the pipe and I exhale, breath extending into the glob, becoming trapped in the expanding mass as my thumb swiftly caps the end of the turning pipe. A bubble appears. Three decades of glass blowing inform my movements and I don’t have to think. I sense how fast to turn based on the resistance of the glass in the crucible, on the way it stretches as I change the angle of my pipe to the ground. I can see, feel and also smell the predisposition of the material, as wood, wax, paper, cork and steel come into contact with the outer surface of my gathers. Mediating my interaction with the glass, all signal the next step, if I am present enough to feel, hear, smell, and follow.

I now overlay a small amount of steel blue onto the clear bubble. My assistant has collected a small fragment of glass saturated with metallic oxides at the end of a long metal rod called a punty. She gradually shapes and reheats it. She presents me with the glowing mass, rotating the punty above her shoulder height so the colour stands above my bubble, waiting. I take hold of the punty with the metal shears in my right hand. I stand at the bench, the pipe held vertically with my left hand, so the bubble points to the ceiling. The colour falls evenly, a perfect oversized raindrop lands on my bubble. I free it from the rod, cutting through its stretching umbilical cord, fingers gyrating the pipe—half a turn left, half a turn right—as I cut, countering the effect of gravity. A mushroom cap. I sit and gently place the pipe on the rails that frame the space of the bench, perpendicular to my seat. I centre the cap, rotating the pipe forward and back along the rails, pressing down with my whole left hand stretched forward as if shaping dough with a rolling pin with one hand.

Every step that follows builds a crescendo of interrelated actions unique to this time and place, a going-along. If glass blowing is a dance, as it is often referred to, our collective experience is more like a tango than a ballet. The material leads and responds, both music and agent, our actions and responses embodied in the work. We are corresponding with the world. (Ingold, 2021, p9)

- Glass team making a body form at Furnace Simone Cenedese, Murano Italy. Nadege Desgenetez, Benjamin Cobb, Thomas Pearson, Catherine Newton and the Cenedese team. Glass Art Society Conference 2018. Photography Catherine Newton and Ann Jackle.

- Glass team making a body form at Furnace Simone Cenedese, Murano Italy. Nadege Desgenetez, Benjamin Cobb, Thomas Pearson, Catherine Newton and the Cenedese team. Glass Art Society Conference 2018. Photography Catherine Newton and Ann Jackle.

- Glass team making a body form at Furnace Simone Cenedese, Murano Italy. Nadege Desgenetez, Benjamin Cobb, Thomas Pearson, Catherine Newton and the Cenedese team. Glass Art Society Conference 2018. Photography Catherine Newton and Ann Jackle.

- Glass team making a body form at Furnace Simone Cenedese, Murano Italy. Nadege Desgenetez, Benjamin Cobb, Thomas Pearson, Catherine Newton and the Cenedese team. Glass Art Society Conference 2018. Photography Catherine Newton and Ann Jackle.

As glass is gathered again, and again, three, four, five times, each layer is coaxed into unison with heat. The work is now heavy, ten kilos of writhing lava. I sit to shape the elongated bubble with a folded wet paper in my right hand. My body stretches to its limits, left foot tucked under the rail located below my body. My torso leans almost horizontally towards the glass, so I can reach and shape what will look like the bottom half of an abstracted forearm. I brace my core, engage my bicep to counteract the effect of gravity while applying deliberate pressure with the pad nestled in my hand. Too much and the form will buckle. I often must stand to sculpt the form more freely, my assistant holding the pipe down. Thin cork paddles separate me from the 1000-degree glass skin.

The bodies of my assistants are at times my body, eight hands turning, griping, squeezing, smoke and hissing amidst sweat and excitement. Our goal is one and the same and a blown glass form is completed, set to rest and cool slowly in the kiln we call an annealer.

Social scientist Erin O’Connor writes that in the heat of the hot shop, glass blowers experience an inter and intra-corporeal exchange. Locale, equipment, materials and bodies are a symbiotic assemblage throughout the making of a work.

- Works in progress, cooled in the annealer. ANU glass workshop, 2019. Photography Nadege Desgenetez.

- Plume in progress, silvered. SevenHills Glass NSW, 2019. Photography Nadege Desgenetez.

Weeks later, in the industrial backroom of a mirroring factory, silver gives the transparent form presence. It becomes a mercurial shapeshifter, an agent of mirror affect (Albu, 2016, p23). By reflecting space and viewers, the work will remain active, mediate encounters, as both object and subject in the space of the exhibition. Adding layers and hours, I seal the fragile silver with a varnish, to protect the mica-like deposit now coating the internal space of the form. Pristine and space-age like today, I know it might weather, show signs of oxidation with time.

- Yusuke Takemura polishing Appear, ANU glass workshop, 2019. Photography Nadege Desgenetez.

- Nadege Desgenetez, Passage 2, background. ANU Drill Hall Gallery 2017. Photography Greg Piper.

Now in the cold working space, laid out like an operating theatre, the slow process of honing the sculpture can begin. Steel tables, saws and rotating abrasive machinery, humans in plastic aprons and protective equipment. My fingers and eyes run over the surface of Passage, conducting a diagnosis of sorts, taking in volumes and voids to find the areas I must sharpen. We use hand-held air tools and diamond-impregnated disks designed for the stone carving industry. The work is loud, wet, slow, and cold. I carve the outline I see emerging from the softness of the curves, sharpening lines, smoothing planes, and creating cliffs to direct the gaze and suggest fragmentation. The better-tuned skills of expert assistants exponentially extend my reach. Pressure is necessary as they spend countless more hours refining my carving and bringing the forms back to a highly reflective polish.

The work finds its anchor with a reclaimed industrial beam.

Passage 2 is of my body. I had scanned my forearm to create the first CNC-routed foam model. It is also of the furnace, of the assistants that support me, of the land, waters and transient skies that abrade, enable, appear, and recede as I shape the piece. It is now of the place held in its reflections, of the people it greets, in its new home, in New South Wales, continuing to correspond with the contexts it is part of.

With my new works, I continue to hone the ways in which I can share these fluid experiences of connection with the world. They are informed by making, always in becoming.

- Nadege Desgenetez, Speculative seeing device, Pilchuck Glass School, Stanwood USA 2019. Photography Nadege Desgenetez and Amie McNeel.

- Nadege Desgenetez, Speculative seeing device, Pilchuck Glass School, Stanwood USA 2019. Photography Nadege Desgenetez and Amie McNeel.

Further readings

Hodder, I 2012, Entangled: An Archeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., Chichester UK.

Ingold, T 2021, Correspondences, Polity Press, Cambridge UK; Medford MA.

Latour, B 2018, Down to Earth, Politics of the New Climatic Regime, Polity Press, Cambridge UK; Medford MA.

O’Connor, E 2015, ‘Inter‐ to Intracorporeality: The haptic hot shop heat of a glass blowing studio’, Studio Studies: Operations, Topologies and Displacements, Routledge, New York, pp 105‐119.

About Nadège Desgenétez

Nadège Desgenétez is an artist and an educator. Glass is her primary material. She has been a lecturer at the School of Art and Design at the Australian National University Canberra since 2005. Her work is represented by Heller Gallery, NY USA; Traver Gallery Seattle USA; Galerie Mouvements Modernes, Paris France and The Something Machine Bellport USA, where she will hold her next solo exhibition, in October 2023.

Nadège Desgenétez is an artist and an educator. Glass is her primary material. She has been a lecturer at the School of Art and Design at the Australian National University Canberra since 2005. Her work is represented by Heller Gallery, NY USA; Traver Gallery Seattle USA; Galerie Mouvements Modernes, Paris France and The Something Machine Bellport USA, where she will hold her next solo exhibition, in October 2023.

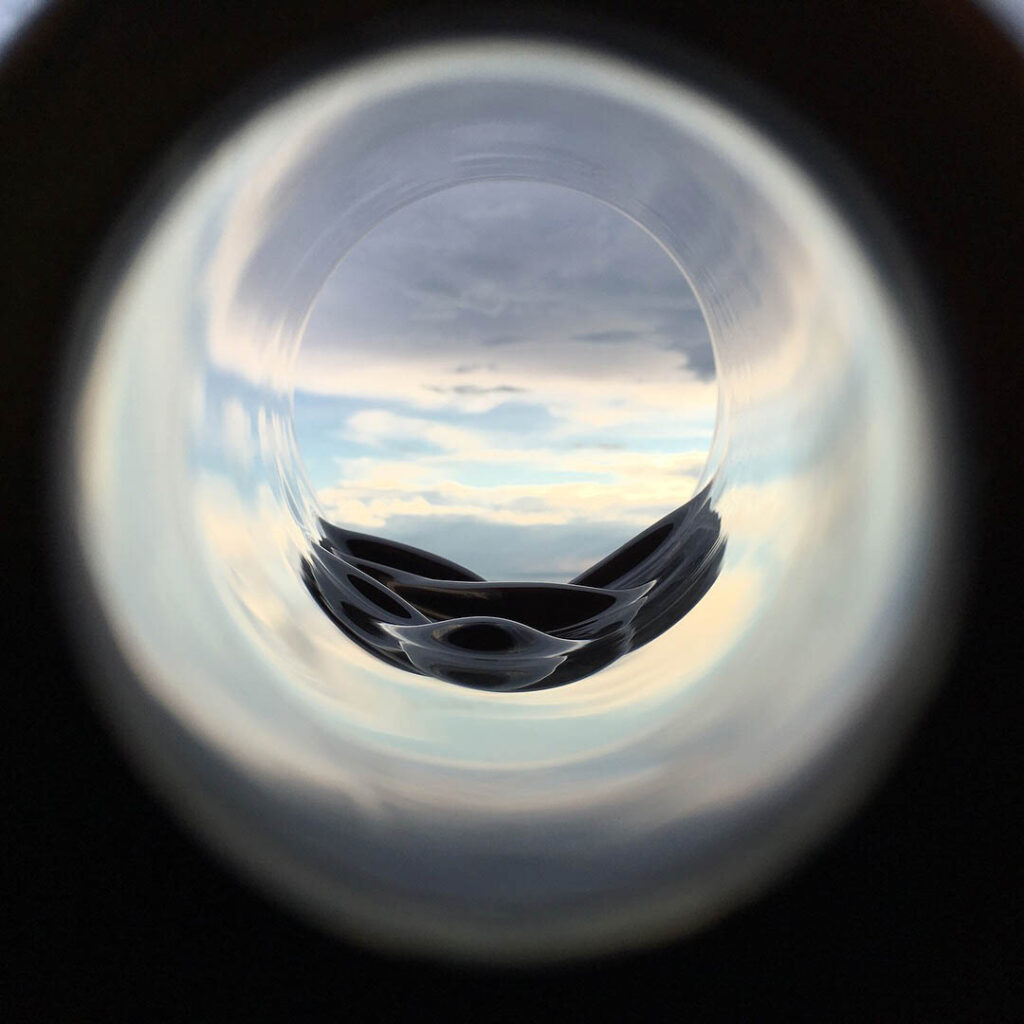

Portrait in Oculus, 2019; photo: Greg Piper.

Comments

An amazing story, thanks for sharing !