Charly Blackburn brings earth and metal together in an alchemic practice that reflects the violence of mining. We ask how, where and why.

(“When Salt becomes King”, a poem by Charly Blackburn.)

Charly Blackburn’s work was profiled by the Royal College of Art, London

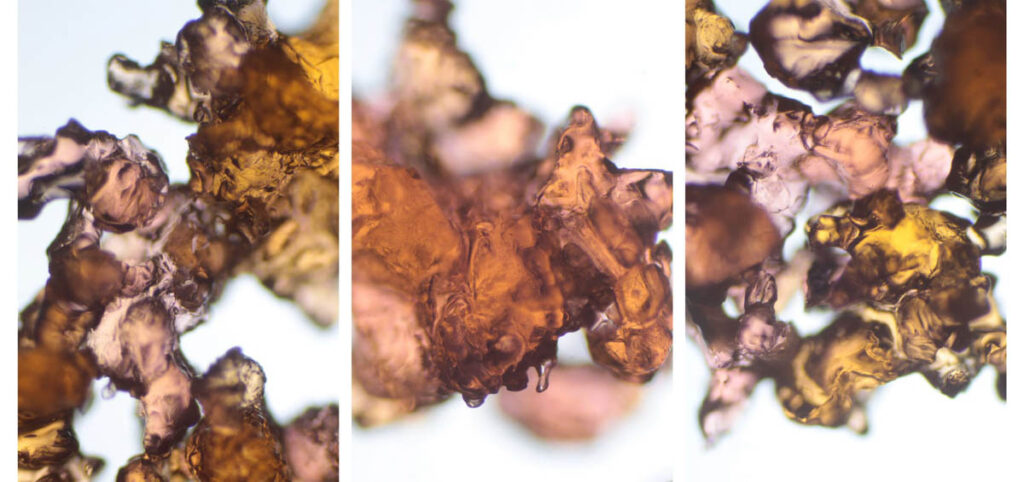

By firing clay alongside other raw materials found within the Earth’s surface, Blackburn aims to discover new behaviours and chemical reactions which mirror the societal and ecological brutality of present and future mining practices.

We thought this was worth a closer look.

✿ Your work requires a complex understanding of mineral sciences. From where do you draw your knowledge?

My interests are broad. Whilst I’m fascinated by materials and minerals, it’s the politics behind them and the stories they imbue which also drive my research. Currently, I’m obsessed with deep-sea mining and the ways in which this remote and mammoth resource could be controlled, and ecosystems lost forever. I try to bring observations and concepts together from the fields of chemistry, biology and craft, creating a tangible perspective. As a voyeur, I look to the worlds of material science and industrial production for ideas. Scientific specialisms can sometimes be limiting. For a thinker/maker, craft offers up a freedom for communication that perhaps science cannot.

Materials are complex, craft processes are complex. It takes time and dedication in order to understand how they behave and how to work with them, hands on. I’ve learnt the most through experimenting with clay, minerals, glass and metals and a variety of making processes. When creating recipes, my technique is both intuitive and scientific, gaining knowledge and modifying processes with each experiment. I forge some form of relationship with the mineral: it’s a dialogue. Clay is a perfect example. It begs you to understand its behaviour, its sensitivities and changes in structure. It’s desperate to be understood, for you to know why it distorts and cracks. It’s why people get hooked. It’s a responsive medium to have great conversations with.

Once you build this kind of relationship, a curious mind wants to know the mineral’s roots, its origin and its material lineage. I imagine minerals like copper, cobalt, lithium and manganese with a life force, a back story and imbued with power. I’m eager to understand how they’ve been used, engineered, exploited and in what way humans get entangled in the hellish exploitation of resource control.

✿ What is the natural home for your work? Is it an art gallery?

The materials have already been extracted from their natural habitat, the ground, and displaced. I wonder if returning them would have the same impact as an art gallery, geological institution, faux chemistry lab, or climate activist intervention could. I’d be excited to work within either of those. Exhibiting to a variety of audiences could teach me a lot about the communication of ideas.

One ambition of mine is to make collaborative work directly from a mining site, whose polluted grounds are rich in heavy metals. Using the raw source material and firing on-site communally, may create strong connections from ground to fired object. With basic processing of ingredients, we could turn toxic waste into colourful ceramic sculptures, illustrating the composition and complexity of the land whilst learning from each other, and hopefully engaging local and global audiences.

Whilst my work really needs to be “seen” in the flesh for full understanding, images and online platforms are perfect to tell stories and reach wider audiences. Often the art gallery feels too subdued. Maybe ceramicists’ voices should be much louder or perhaps there’s a powerful resistance in the quieter offerings. The scary thing with deep-sea mining is that it’s all happening below the surface and in secret. I’ve started to connect with scientists and environmental protection organisations in the hope of illuminating the wider implications.

✿ While reflecting the violence of mining, your work itself is quite beautiful. How do you resolve this contradiction?

It’s not a contradiction, art is often beautiful. It’s kinda the point. It can be beautiful but also violent. I want to spark a curiosity, a wonder, a material ambiguity. If I’m trying to forge connections between mineral and object and demonstrate the essence of this “beautiful” mineral that we want to protect, then it first needs seduce. The fantastical crystalline glazes, for example, do just this. Most uses of cobalt are disguised within batteries or devices, I’m trying to unlock its alternative material potentials that have no practical application.

Simulating the temperatures of the inside of a volcano, in a gas-fired furnace bin, to me, elicits violence. I choose this very hands-on firing approach for specific works, adjusting the temperatures intuitively whilst the gas torch roars. Peering into the vent hole, molten wares glow orange like the earth’s magma core. The making process is just as important as the materials used within the work, the processes carry with them an energy, a force, inevitably becoming embedded within the object.

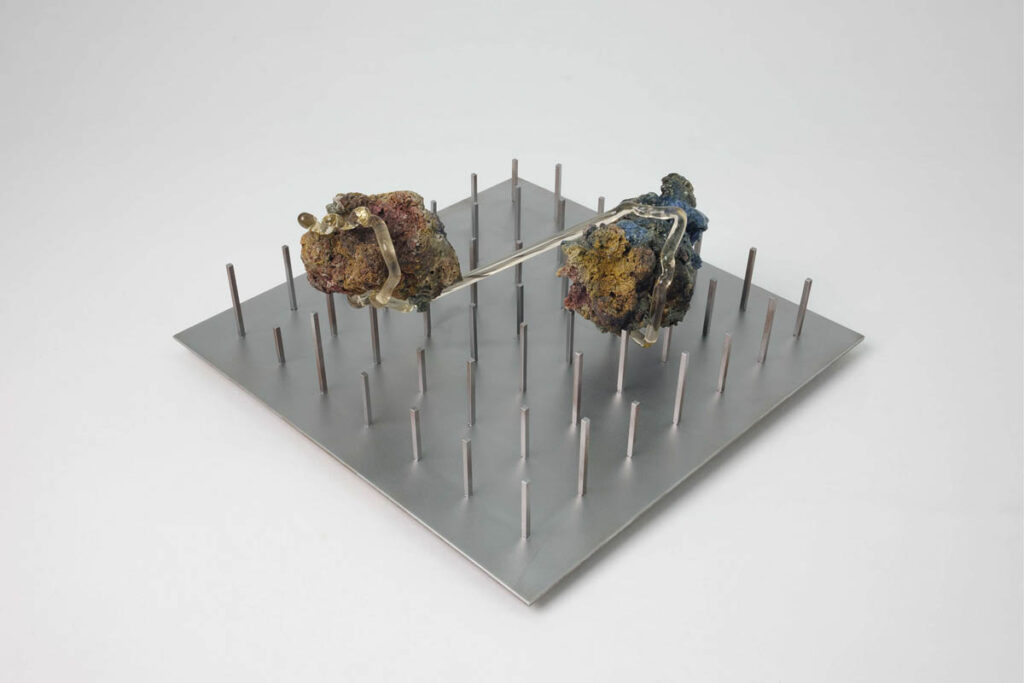

There is also a discomfort in some works, something unsettling, a conflict in form, whether it be dangerously fragile glass lampworked around molten nodules or uncomfortably seductive precision. There is usually some kind of tension or contrast.

✿ Would you support any particular kinds of mining practices?

I’m not opposed to mining minerals and using resources from the ground. I’d be a hypocrite if so. I’m yet to find a mining operation that doesn’t involve stealing land, ecological devastation, slavery or labour abuses. It’s horrid on every level. The power structures at play and modes of governance are not withdrawing, but using greenwashing strategies whilst increasing their speed of extraction.

I’m an advocate for limiting the amount of metal in circulation, rather than total depletion. Still baffled by the UK’s recycling system, I want to see recycling become as sophisticated as microchip engineering. Any mine, closed or in operation, has an obligation to remediate the land it destroyed. There are some exciting potentials happening in the fields of biomining and phytomining, not that they compare to the efficiency and scale of current extraction methods. We all have a role to play in shaping the future individually and collectively.

✿ The RCA website mentions that you were investigating faience. Does that still play a role in your work?

Faience was a pivotal discovery for me. Firstly, it doesn’t technically contain clay, which blew my tiny mind. Secondly, salts migrate during the drying process and the iconic turquoise glaze happens due to the chemical reaction on the surface of the piece, aka “the self-glazing ceramic”. When faced with an increasing amount of technological possibility, the ability to re-create a recipe from 6,000 years ago and have the same result was profound. Whilst ruminating over modernity and specialisation, that project was the catalyst to start thinking about our connection to land in a multidimensional way.

Gods and goddesses who reside in the flood plains of the Nile have been made into faience figures. In the 1970s, the Aswan dam was completed, which disrupts the annual flooding of the river Nile. The once-worshipped river with its fertile plains has since culminated in salinated soils, rendering parts of the land virtually incapable of agricultural cultivation.

Salts are underappreciated, magical and powerful. SALT will reign again. Not only can it penetrate and move through metals and rocks and destroy skyscrapers, but living things also depend on it. Too much salt is deadly, but without it, we’d die. In ceramics, salt has the ability to change the composition of the structures I create, migrating through forms and taking oxides with it, it diversifies melting temperatures. There is also something exciting happening at the chemical level during long periods of drying, but I’m yet to confirm exactly how the molecules are behaving.

About Charly Blackburn

Originally from The Fens, Charly Blackburn is a ceramicist and technician based in London. The Art Institute of Chicago features collaborative work between Blackburn and artist Himali Singh Soin in Soin’s project Static Range, Dec ’22 – May ’23. She is currently writing an article for Textura Magazine titled “A DeepWarning. Mining the ocean floor, craft and sentient materials”. Visit www.charlyblackburn.com and follow @churlyblurburn_

Originally from The Fens, Charly Blackburn is a ceramicist and technician based in London. The Art Institute of Chicago features collaborative work between Blackburn and artist Himali Singh Soin in Soin’s project Static Range, Dec ’22 – May ’23. She is currently writing an article for Textura Magazine titled “A DeepWarning. Mining the ocean floor, craft and sentient materials”. Visit www.charlyblackburn.com and follow @churlyblurburn_