David Cheah works with the monks of the Lao temple Wat Siphoutthabaht to produce an outdoor installation for the festival of Boun Ok Phansa.

(A message to the reader.)

On my first visit to Luang Prabang 21 years ago, I remember flying in low over its highest point, Mount Phousi crowned by the gleaming golden spire of Wat That Chomsi. Some 30 trips later, I still find myself peering out the cabin window trying to get a glimpse beyond the cloud cover. My initial motivation to visit was its UNESCO World Heritage Site listing in 1995 for well-preserved architecture. I was drawn to the elegantly curving temple rooflines. Once within, I became intrigued by the intertwined stencilled patterns. I felt a sense of familiarity and connection as though I had seen variations of them before. It took me back to my childhood days of trying to unravel eternity knots.

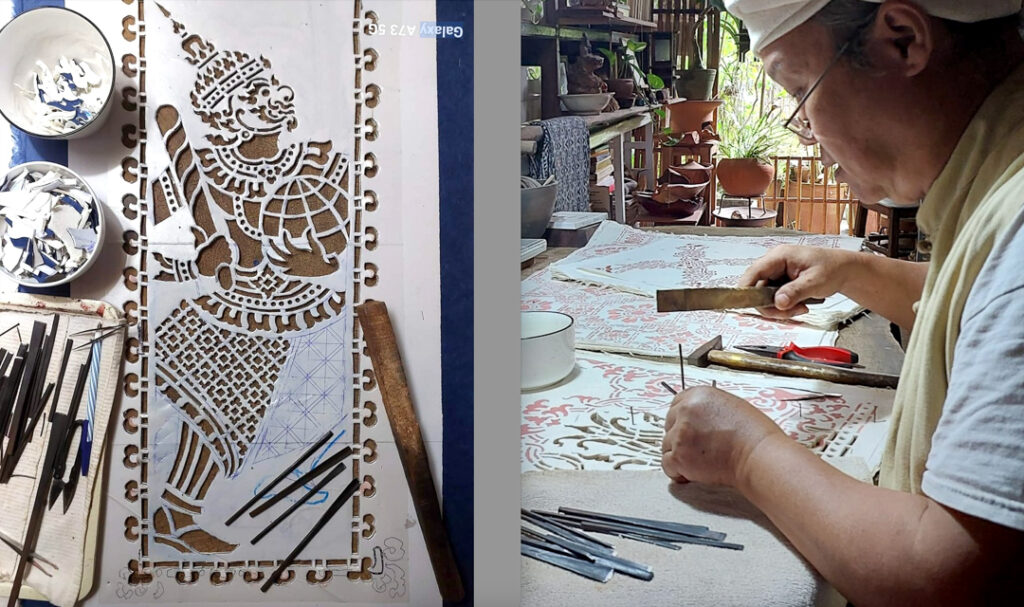

At a gathering of arty types, I met the Luang Prabang-born French artist Tiao David Nithakong Somsanith (aka Tiao Nith). Whilst internationally known for his gold embroidery and stencil art, he is also passionate about the preservation of traditional Luang Prabang art and culture. We share a common interest in the art of stencilling. He uses the traditional technique of cutting handmade mulberry saa paper.

My first temple stencilling experience came when I was invited by Tiao Nith to participate in the restoration of Wat Pak Khan Khammungkhun, at the mouth of the Nam Khan River. Originally stencilled with gold leaf but due to budget constraints, most of the stencilling in temples is now done with commercial metallic paint. I was nervous but excited at this opportunity to work on temple walls that have stood for nearly 300 years. I was relieved when Tiao Nith pointed out that there was no one correct way to stencil. I could see the variations left by different hands and felt a sense of belonging to the community in our merit-making contributions to the temple. For me, these intertwined patterns are like visual metaphors of life’s interwoven journey with the shared experiences and connections we make along the way.

The origins of this temple stencil art form are obscure. Intertwined patterns, sometimes incorporating religious motifs, are used on walls, columns and ceilings. Stencilling is also used in compositions that depict a story or parable.

Rather than using traditional patterns, he cut stencils depicting the life of the monks from the morning almsgiving to the daily chores

One of the fascinating developments I have observed is a group of monks becoming passionate about preserving this art form. A few years ago, Tiao Nith started training monks to stencil. When Wat Siphoutthabaht Thippharam was undergoing renovations, he took the opportunity to design a mural for the monks’ dining area. Rather than using traditional patterns, he cut stencils depicting the life of the monks from the morning almsgiving to the daily chores and even down to the detail of the dogs and cats living in the compound. The use of these everyday elements in the designs created an immediate connection with the monks who then enthusiastically stencilled the walls themselves.

This year, the same team of monks under the guidance of Sadhu Somkiet Siyangvongsar (aka Sadhu Obee) are working on the restoration of a temple patronised by Tiao Nith’s family, Wat That Luang Rasamahavihan. I was to have helped with the wall stencilling but they wanted to finish the windows and doors first. These were completed before the light festival hence it was an opportune time to share their achievements. They proceeded to make stencilled fabric duplicates for their archives and I was tasked with finding a way to display their work for the festival.

- The outdoor installation Temple without walls, viewed from the front

- Under the light of a full moon, Sadhu Obee next to the kathin offering stencilwork

- Fabric hanging detail of the kathin offering ceremony

- Reflection and candle offering

My favourite time to visit Luang Prabang is during the light festival Boun Ok Phansa which is then followed by the fire boat parade festival, Boun Lai Heua Fai, which marks the end of a three-month rains retreat for monks. It is a magical experience because the temple grounds are lit up. More than a visual feast, for me it is like a little pilgrimage walking from temple to temple up side streets and cobbled laneways with the delicate scent of the tree jasmine adrift on the night breeze. At the temples, the air is suffused with the scent of beeswax from hundreds of candles and tealights while I am lulled by the evening chanting of monks.

I saw this installation as an opportunity to use the window and door designs metaphorically as openings inspiring insight and reflection on our lives. In a way, an invitation to open our minds to other possibilities beyond the confines of the walls that we know and have built.

Working off and on for about 10 days with a team of monks, I am full of admiration for them. They must juggle daily chores, monastic duties and studies including Sadhu Obee who is studying architecture. We chatted about architecture and influences found in the temple. One curiosity is carved door panels depicting European attired emissaries and another is Chinese figures in the wall murals. The murals themselves are based on the Phra Lak Phra Lam, a Lao adaptation of Indian Ramayana stories just like the window and door panels in the installation. Thus, the idea for the outdoor installation Temple without walls evolved from the history of intercultural openness and connection at Wat Siphoutthabaht.

- A monk stencilling a window panel at Wat That Luang

- A monk stencilling a fabric panel reconstruction of a window design

- Novice monks making lanterns

- A monk stencilling a window panel at Wat That Luang

- A window at Wat That Luang before and after restoration with a proud Tiao Nith

- Tiao Nith using traditional tools to cut stencils from mulberry paper

- Monks depicted on a stencilled lantern in their work area at Wat Siphoutthabaht

- European influence on doors carved with emissaries at Wat Siphoutthabaht

Referencing a temple layout, the stencilled fabric panel reconstructions of window and door designs were hung from bamboo structures in an arrangement similar to the originals at Wat That Luang. The setting up of the installation was a very hands-on affair with many elements made from scratch. Materials such as bamboo had to be procured at a time when it was in high demand for building parade boats. Sadhu Obee managed to chop some down at his mother’s home. Meanwhile, some novice monks worked on stencilling paper lanterns. Occasionally a rumble in the overcast autumn sky was followed by nervous laughs. Normally, the promise of rain on a scorching day would be a welcome blessing but not around the time of the light festival when most of the lanterns and boat structures were made of paper.

At the heart of the installation was a long hanging depicting the robes offering kathin ceremony that takes place during this Ok Phansa festival. Symbolically lit from within, it was a reflection on the temple, the community we build and ourselves as the vessel; vessels for passing the light on.

Each year there are friendly rivalries between temples to build bigger and fancier boats for the parade. We decided instead to turn the focus back to the importance of the individual and our humble intentions in reconnecting and reflecting on the divine that resides within each of us, no matter what colour or creed. Symbolically, this year we had four small boat-inspired elements situated to represent the corners of the world. Carved banana stalks were used to construct the boats and offering “altars”. This skill was taught to the monks by a Thai master who feared the art form would die out in his homeland. These were adorned with wax flowers and recycled wax candles which reference the old practice of wax offerings to monks for candle making before the advent of electricity. Volunteers including Australians, Thais and Lao contributed to this installation whilst people from all walks of life were invited to make and leave their candle offerings. This was an invitation to reflect on our place and our journeys.

Photos by Tiao Nith, Sadhu Obee and David Cheah

Further Reading

- https://www.luangprabangculture.com

- https://garlandmag.com/article/devotional-flower-offerings-of-luang-prabang/

- https://garlandmag.com/nithakhong/

About David Cheah

Based in Sydney, David is a Malaysian-born artist who has exhibited in group and solo shows in Kuala Lumpur, Luang Prabang, New York, Penang, Singapore, Sydney and Vientiane. With a creative journey from architecture to art spanning 30 years, his works blur the boundaries between art and design. Luang Prabang is his favourite go-to place. He finds inspiration in textiles, travels and intercultural connections. All the better if he can marry them into an enriching experience! Visit sites.google.com/view/david-cheah-artist

Based in Sydney, David is a Malaysian-born artist who has exhibited in group and solo shows in Kuala Lumpur, Luang Prabang, New York, Penang, Singapore, Sydney and Vientiane. With a creative journey from architecture to art spanning 30 years, his works blur the boundaries between art and design. Luang Prabang is his favourite go-to place. He finds inspiration in textiles, travels and intercultural connections. All the better if he can marry them into an enriching experience! Visit sites.google.com/view/david-cheah-artist

Comments

Thank you for this wonderful article David! I so enjoyed reading about the Light festival and the origins of this spectacular installation.