Miranda Hine is intrigued by the words cut by Ally McKay, which reflect the social disjunction of the pandemic.

(A message to the reader.)

The recent work of Meanjin/Brisbane-based artist, poet and educator Ally McKay positions language as a physical medium through embossing, laser cutting, and shadow.

For the last decade, Ally’s sculptural installations have explored vulnerability, support, connection, rules and isolation. In retrospect, it seems as though she was making work about the pandemic experience before the pandemic happened. It is no surprise, then, that I find these themes distilled further for her latest solo exhibition A P A R T, on display at Queensland College of Art’s Project Gallery, 7 – 23 April 2022.

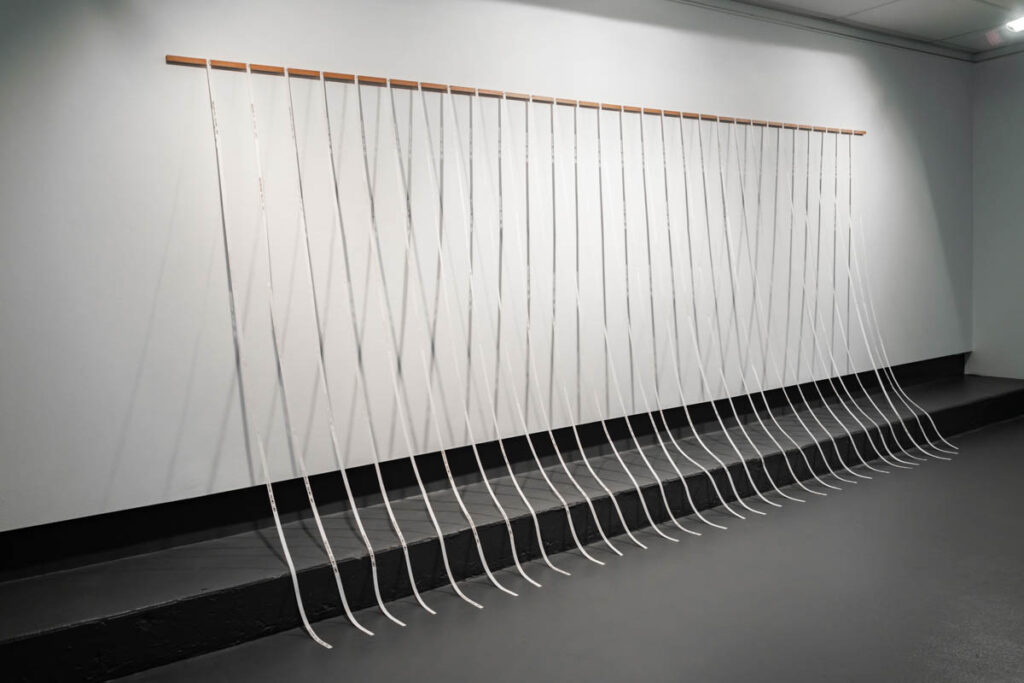

- Ally McKay, The Great Escape – Not Going Anywhere, 2022, wood and paper cut installation, 200 x 450cm, photo_ Louis Lim

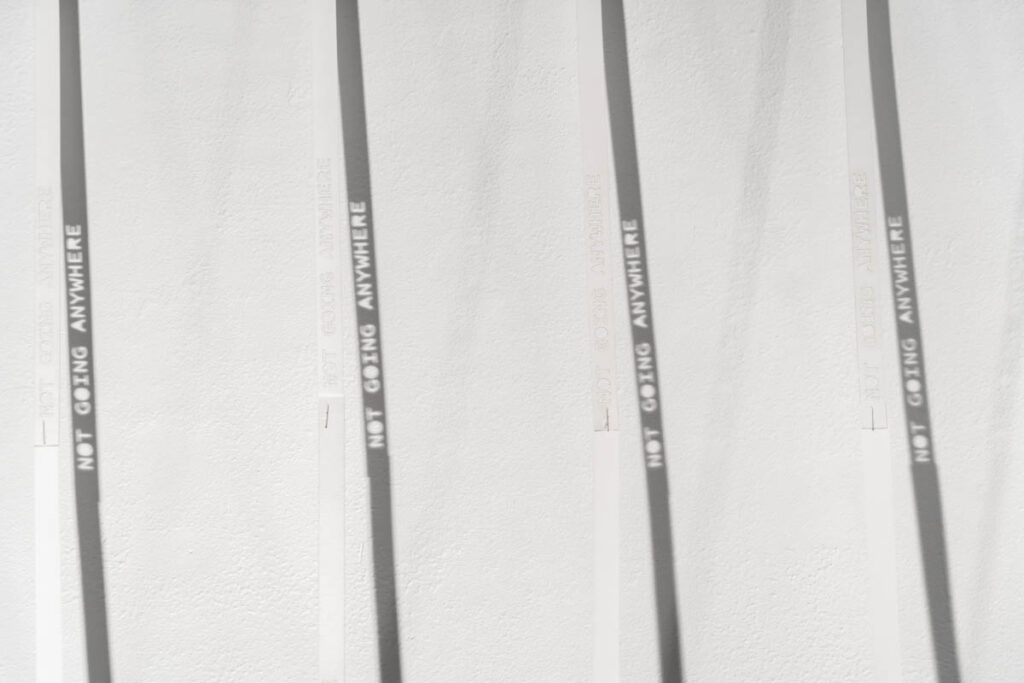

Seven installations range in scale from 30 to 450 centimetres, each positioned on the gallery floor or wall. The largest, The Great Escape – Not Going Anywhere (2022), consists of 29 thin paper strips draping down the wall and onto the floor. Up close I can see each strip is actually smaller paper pieces precariously stapled together, each with the phrase “not going anywhere” cut out. The phrase is a direct reference to the lockdown experiences of the COVID pandemic, but has a dual suggestion of support, as in a phrase you might say to a friend who’s going through a difficult time. In keeping with Ally’s fascination with physical structures of support as stand-ins for emotional ones, this sentiment is echoed through the staple joins. If one join tears, the whole length is broken.

The most striking part of this work, however, is the shadow cast by the carefully directed lighting through the cut-out words, seeming to strengthen the paper strips by echoing their structure on the wall behind.

Paper and words have remained two constants in Ally’s practice, but the way she integrates them has evolved. Previously hand-cutting words out of paper, Ally has transitioned to laser-cutting as the technology has become more available to her. When I ask her about the transition, she is in two minds. Laser cutting allows for faster work, which means more tests and experimentation on the one hand. But she feels it also removes the artist’s hand from the process (not necessarily a bad thing, she admits) as well as the meditative aspect of cutting by hand. One clear benefit of the new technique, however, is the ability to play with new mediums.

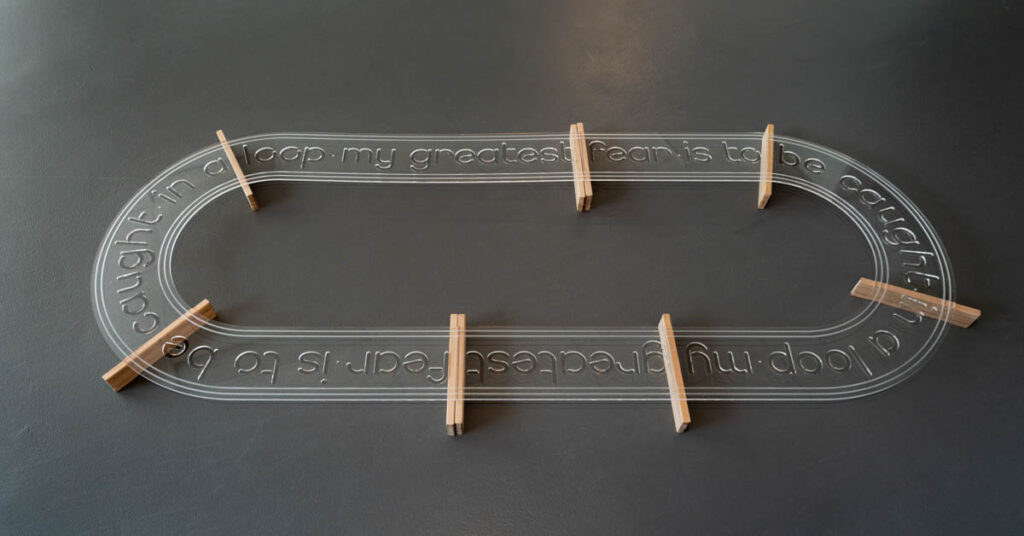

My Greatest Fear (2022) features a large oval sheet of acrylic balancing on low wood supports on the gallery floor. A continuous loop of the words “my greatest fear is to be caught in a loop my greatest fear is to be caught in a loop” have been removed by laser from the acrylic. This work signals Ally’s experimentation with harder materials, as the translucency of the acrylic attempts to replicate the tension between solid and fragile that the paper works so successfully evoke.

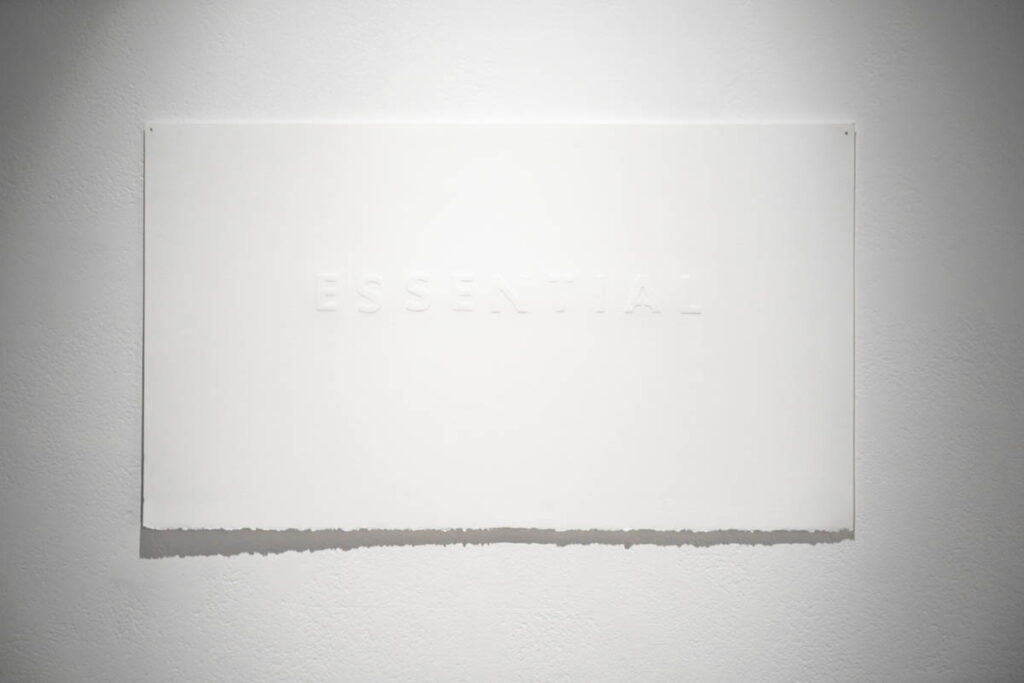

The sharp laser cuts contrast with more subtle lettering in the works ESSENTIAL (2022) and Border to Border (2022), which each use embossing to imprint these words into white paper. From afar, the text is barely distinguishable, and light and shadow again become important mediums in revealing it. Their physical ambiguity mirrors the constantly changing meaning of these words over the course of the pandemic. The word “essential”, which appears again and again in these works, was used during the pandemic to define certain professions and not others. In particular, Ally found herself being defined as “essential” as a teacher aide but not “essential” as an artist or maker. These definitions, which did not necessarily align with her own understanding of her different roles, inform Ally’s recent work as she attempts to navigate the arbitrary and external labelling of her worth. Through the repetition of these words, Ally asks us to consider their meaning and impact afresh.

Ally McKay, A P A R T II, 2022, wood and paper cut wall installation, 20 x 30 x 8cm, photo_ Louis Lim

The smallest work in the exhibition is the wall-mounted sculpture A P A R T II (2022), in which the letters A, P, A, R and T are individually cut from paper—this time in the positive rather than negative—and each attached to the wall with a single pin. They hang above a stack of 15 small wooden blocks supported by a slightly larger wooden length. Together, the wooden pieces are solid—they are all a part of something. But in their togetherness, they also become increasingly precarious, ready to tumble to the ground with a slight touch.

Ally’s works have perhaps never been more relatable. Through familiar words and cleverly balanced structures, they attempt to articulate the experiences of the past few years: navigating changing rules and systems, supporting others by being away from them, connection and isolation, shared experience and loneliness. Negative space and shadow become the medium, so what’s missing is just as important as what’s there. These works are quiet, reflective, and would perhaps each benefit from their own gallery space. The more space around them, the more intimate, isolated and essential they seem to be.

You can learn more about Ally’s practice at www.allymckay.net

About Miranda Hine

Miranda Hine is a curator, writer and artist from Meanjin/Brisbane. She is a settler Australian woman of European ancestry living and working on unceded Turrbal and Yuggera land. Her research revolves around the role of museums in constructing and perpetuating particular narratives, and how we can disrupt them. As an extension of her curating, writing and research practices, her art practice investigates our instinct to create stories and connections when objects, text and images are placed next to each other. Miranda has exhibited in multiple group exhibitions, curated exhibitions in museums, galleries and ARIs, and written for artists and publications around Australia.

Miranda Hine is a curator, writer and artist from Meanjin/Brisbane. She is a settler Australian woman of European ancestry living and working on unceded Turrbal and Yuggera land. Her research revolves around the role of museums in constructing and perpetuating particular narratives, and how we can disrupt them. As an extension of her curating, writing and research practices, her art practice investigates our instinct to create stories and connections when objects, text and images are placed next to each other. Miranda has exhibited in multiple group exhibitions, curated exhibitions in museums, galleries and ARIs, and written for artists and publications around Australia.