We’re on the highway from Samarkand to Tashkent. It’s 40c outside, but it doesn’t stop the driver from winding down his window to have a cigarette, while simultaneously checking his Facebook account and maybe keeping half an eye on the road ahead.

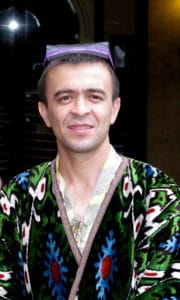

The ikat maker Aziz Murtazaev had generously taken time to show me around Uzbekistan’s ancient city, particularly it’s sumptuous suzani textiles and the idyllic village of Koni Gil. I’ve been impressed with how much care Aziz takes talking with our hosts, offering detailed advice on artistic and business matters. He seems a natural leader, so to take our minds off the scary driving, I ask Aziz about his background. It’s not what I was expecting.

Aziz was born in the Uzbek town of Margilan, in the fertile Fergana valley on the border with Tajikistan. His father was an engineer who encouraged his children to study and particularly to learn languages. Aziz studied English at school then university. He gave English classes to the elderly and provided services as a guide around Fergana valley. It was during this time that became familiar with the craft scene: “In Fergana valley, you don’t have many sights for tourists, but plenty of crafts.”

After university, Aziz worked in marketing for a silk factory in Margilan that had been established in 1958, during the Soviet Union. It had over 300 people and Aziz spent some time as an apprentice learning the binding process for silk threads.

After a year, Aziz went to study finance in Kyrgyzstan and took up a career in banking as a loan officer. “Maybe I was genetically favoured to be good at mathematics.” Much of the micro-financing involved craftspersons, which introduced him to the challenges of running a craft business.

After three years, Aziz went to England to improve his knowledge of both finance and English. He stayed there for two years until he was 28 years old when he received the fateful call from his father to return home and get married. They had found a wife for him, as is the tradition.

Back in Margilan, Aziz developed a business marketing silk ikat. In partnership with other masters, Aziz helped improve the quality of the craft products, which he took to Santa Fe between 2009 and 2016. His work met with great success and he was able to restore block printing, the finishing of fabrics with egg-white and develop new types of scarf with raw silk and natural dyes. This eventually led to the award of the UNESCO Seal of Excellence.

In 2016, he went into business on his own producing ikat. He focused on giving job opportunities to women from rural areas and specialised in dyeing. “The customer first likes the colour, then the motif, then the fabric. I try to product colour-fast according to European standards using natural dyes.”

Despite the allure of finance, Aziz decided to stay with this career. “After the UK, I had a lot of offers from banks to work with them. I had a feeling that just earning the money is not enough. You should do something for other people as well. The knowledge I got from working at the bank, gave me the idea to develop craftsmanship. The knowledge of finance helps me a lot to develop my craft.”

Along the way, Aizhan Bekkulova from Kazakhstan convinced him to join the World Crafts Council-Asia Pacific, with the support of Iran. He was one of the first artisans to join as a national entity. He is now working with the Ethical Fashion Institute in Switzerland on a project to enable poor communities to work with luxury brands, including Addidas and Chanel. “I never say I employ somebody, I say I work with them. They are independent artists collaborating with me.”

Aziz is pleased that his country has invested so much in this craft festival. “Other countries from Central Asia and beyond can see Uzbekistan as a model.”

Like all Uzbeks, Aziz belongs to a mahalla, the universal social unit of the nation. His is called Yangi bogh, which means “new park”. It is the largest mahalla of Margilan city, with over 550 families. Many of the families are artisans, including ikat makers, shoemakers and metalworkers.

But in the end, what Aziz values most is his family. “It is important to do everything with your family. They give inspiration and support. Your children will then be very interested in continuing. Already my sister, wife and mother are very good in making products.”

What’s striking to me about the life of Aziz is how it contrasts with the usual generational drift in crafts. Faced with the increased competition through globalisation and cheap imports, masters are often happy for their children to follow a career that would get them a comfortable and secure office job, such as accounting. The financialisation of the global economic system means that far greater profit can be had from moving money around than actually producing things. It’s assumed that once these children are used to the air-conditioned comfort and security of a fortnightly salary, they are unlikely to return to the rigours and precarity of their family’s craft workshop.

But a life spent in spreadsheets is not necessarily “a good life”. A recent article by Judy Frater draws on interviews with alumni of the academy who say that the independence of a craft career is more important than money.

It’s a testament to Uzbek culture that it has the strength to pull back someone like Aziz from a comfortable job in London. He is back home making a contribution to his country, his mahalla and his family. May there be more like him.