- Ilkhom Bobomurokov with his son Mehroj.

- Ilkhom Bobomurokov making a dragon to welcome guests to the Handcrafters Festival in Kokand.

- Works from the studio of Ilkhom Bobomurokov

- Ilkhom Bobomurokov demonstrating in Kazakhstan.

- The back of the cearmics studio.

- The stream runs through Koni Gil

The ancient Silk Road was not only an extensive thoroughfare, linking trade and traffic from far West to far East. It was also a platform for this trust on which trade was possible.

According to Uzbeks, well before electronic banking, it was possible for an order to be made in China and payment made further down the road in Uzbekistan. This was thanks to the fastajah system that flourished in the Islamic world, which involve promissory notes or cheques (derived from the Persian word sakk, transmitted to the West as an Arabic loanword).

While the Silk Road has today been replaced by the much more formal financial system underpinning Belt and Road, there is still a system of knowledge exchange that supports craft development across the region. This is evident in the story of a ceramics studio in Koni Gil.

Koni Gil is a village of Samarkand nearby the Mausoleum of Daniel, a Jewish prophet who is revered in Islam. This idyllic village is famous for the ancient paper mill and the ceramics studio of Ilkhom Bobomurokov and his son, Mehroj.

Like his compatriot Aziz Murtazaev, Mehroj returned to craft after a detour in finance. But his trajectory was particularly facilitated by the exchanges that still occur across the old Silk Road.

Initially, Mehroj studied finance. After a year at the bank college, he joined the regional Samarkand tax office. This opened his eyes to the business issues he father faced and nurtured the dream to build a proper workshop for his father.

When President Shavkat Mirziyoyev took office, he made a decree to establish sixty new craft centres around Uzbekistan. This prompted Mehroj to apply for authority to obtain land for the new workshop, and he eventually quit his tax job to focus full-time on the ceramics business.

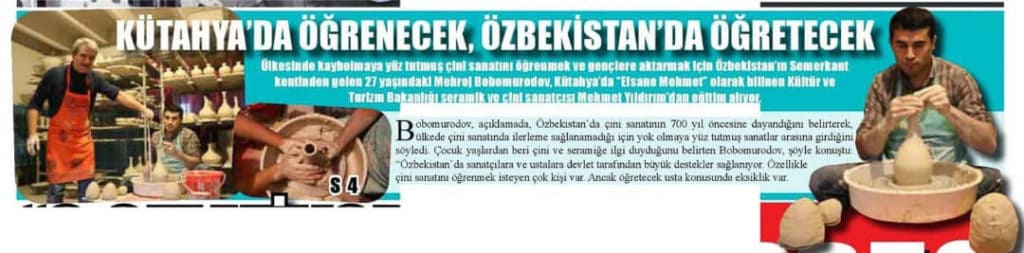

- Press coverage of the residency of Mehroj in the workshop of Mehmet Gildirim

Artistically, the focus was on reviving Afriasab, an ancient technique using white clay and inspired by Chinese ceramics. While participating in a Tashkent fair, Mehroj met the Turkish ambassador, whom he asked to help with finding a master to teach him how to work with white clay. The following year, the master Mehmet Yildirim was invited from Turkey. In Uzbekistan, he gave master classes at the workshop for young students, demonstrating how to work with white clay. In return, Mehroj was invited to Kütahya, a city in western Turkey, where he stayed for 20 days, gathering all the recipes for clay and glazes. “The master was very kind and generous in offering advice.”

While in Turkey, Mehroj discovered that working with a foot wheel is important to artistic expression. The result was a vessel out of white clay that was much taller than would have been possible with ordinary clay.

Since then, Mehroj has been disseminating the technique he himself had learnt. A recent workshop in Astana, Kazakhstan, demonstrated the use of the wheel to students of lesser abilities.

The story of Koni Gil ceramics illustrates both the importance of family in growing local production, but also the very productive exchanges that are possible with the hospitality that is characteristic of the region. One proposal emerging from Garland’s focus on Central Asia is to develop a network of these workshops, open to exchange. Crafts along the Silk Road will continue to flourish.