Gary Warner revisits the “musical playground” created by two French brothers to orchestrate industrial steel for human enjoyment.

Inspiring Japanese musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto experienced the Baschet Sound Sculptures at the 1970 World Expo in Osaka when he was 18. Having been interested in unusual approaches to music and sound creation since my teen years (in the 1970s), I was surprised and thrilled to encounter three of these unique inventions, restored and exhibited at Osaka’s Expo ’70 Commemorative Park in 2017. Succinct interpretation panels for each instrument include photos of their original installation.

The Baschet brothers were French siblings born in the early twentieth century who both lived into their 90s. François wanted to be a sculptor, and Bernard studied engineering. In the 1950s, they combined their knowledge, skills and interests to develop a unique methodology of musical instrument production and sonic generation. They wanted to create new sounds for a new world, sounds of joyful strangeness emanating from innovative instruments that anyone could play without instruction. In later life, they focussed on adapting their signature instruments for education contexts, especially for disadvantaged children.

The Baschets were invited to be part of the 1970 World Expo by avant-garde composer Toru Takemitsu who had been involved in the beginnings of Fluxus and was an influential creative figure in Japan. Through 1969 François, architect Alain Villeminot and assistants designed and built 17 new instruments in Osaka, each named for one of the Japanese workers.

Their orchestra of unique sonorous sculptures was displayed in the spacious foyer of the Japanese Steel Federation Pavilion, which commissioned and generously funded the works. The pavilion’s theme was ‘Song of Steel’, thus the invitation to the Baschets who had developed an international reputation for their unique ideas and work.

François and his team crafted various forms of industrial steel—sheet, rod, ingot, fixings—into formidable, wilfully avant-garde sonic constructions. All Baschet Sound Sculptures were designed to be acoustic, their sounds being locally amplified by plate membranes, resonator cones and sympathetic vibration. They require no electrical power, but some of the sounds they generate are very similar to sounds made by electronic synthesis.

An essential aspect of the original Expo installation was that visitors could freely interact with the sculpture-instruments to generate and experience their unusual, fascinating sounds. François described it as “The world’s first and biggest musical playground.”

In the pavilion’s 1,000-seat ‘Space Theatre’, Toru Takemitsu presented his new compositions and ‘Free Music’ performances with the Baschet instruments as part of daily programmes. The purpose-built auditorium was fitted with a mobile stage and 1,300 loudspeakers amplifying 12 sound systems to create what must have been exhilarating surround-sound experiences. The theatre still exists but when I visited in 2017 was a silent museum artefact.

After the World Expo ‘70 wound up, the gates were locked, the instruments were dismantled and stored, and many of the buildings were demolished over time. Remarkably, when the site was reactivated in 2009, before the 40th anniversary of the event, the instruments were rediscovered. A series of them have been gradually restored, beginning with Ikedaphone in 2009. When the site became a public park and tourism attraction in 2010, it was reinstated in the extant Japanese Steel Federation Pavilion, now the Expo ’70 museum.

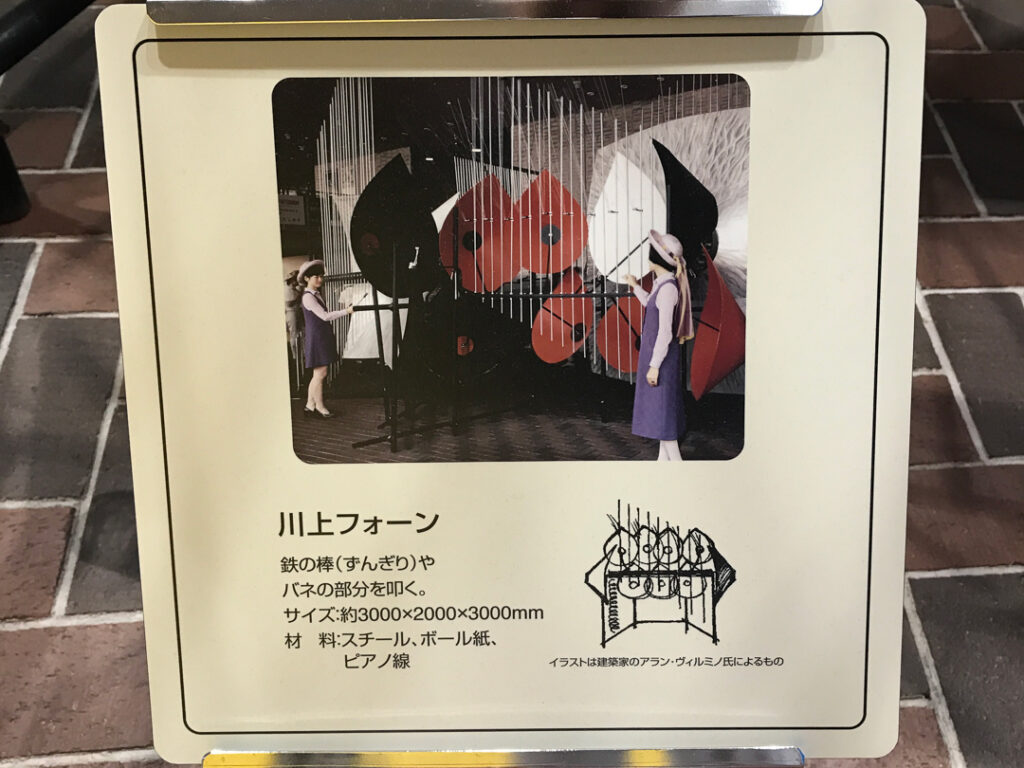

Masatoshi Kawakami, an assistant on the original team, restored Kawakamiphone and Sekinephone in 2013. Watanabephone and Katsuraphone were resurrected by the Kyoto Art Center and Kyoto City University of Arts in 2015. The Tokyo University of the Arts restored Katsuharaphone in 2017 as part of the Baschet Restoration Project, in collaboration with the Baschet Association of Japan and Dr Martí Ruids who leads the Baschet Soundsculpture Workshop at Barcelona University, Spain. It was Ikedaphone, Sekinephone and Kawakamiphone I was fortunate to encounter on a rainy day in Osaka in 2017.

Les Sculptures Sonores – as the brothers named their instrument family – are a peculiar combination of minimal aesthetics and evident function. The materials are unashamedly industrial, more redolent of an engineering workshop than a luthier’s studio, including long lengths of threaded rod and wire, springs, nut and bolt fixings, panel-beaten metal sheets, fibreglass and cardboard. The most exotic material is probably the varying length glass rods of their ‘Cristal Baschet’ family of instruments. For Expo ’70, a restricted colour palette of black, white and red was used, perhaps to emphasise a connection to constructivism and other revolutionary art movements. Perhaps in reference to the fine black and red urushi lacquer finishes of many traditional Japanese crafts. Probably a little of both.

Even though the Expo ’70 Baschet Sound Sculptures are imposing, wrapping above and around their players, each extends an invitation to anyone to actively make complex sounds, to play, explore and discover through engaging multiple senses and deeply listening. Some, like the Ikedaphone, require dynamic physical movement, while some, like the Sekinephone, respond to delicate touch.

Ikedaphone being played by Kathryn Bird (l), Sekinephone, a type of ‘Cristal Baschet’ (r), Expo ’70 Museum, Osaka. 2017. photo: Gary Warner

Since the rediscovery of the mothballed Expo ’70 Baschet instruments, a resurgence of interest has resulted in their collaborative restoration by the Baschet Association of Japan, Association Structures Sonores Baschet in France, and the University of Barcelona’s Baschet Soundsculpture Workshop led by Dr Marti Ruids. The Japanese Baschet instruments aren’t locked up silenced artefacts. They are frequently used by contemporary artists, performers and musicians for concerts and by exhibition visitors in supervised encounters.

The 50th anniversary of the Osaka Expo and the 100th anniversary of François’ birth was 2020. Unfortunately, restrictions surrounding the COVID pandemic meant that many planned events were cancelled or reduced. One significant project that did go ahead was a stunning exhibition at the Kyoto City University of the Arts Gallery. Comprehensive photographic and video documentation can be viewed at the link below in Further Reading.

Installation view of Baschet Sound Sculptures, Kyoto City University of Arts. 2020. photo: Tokeru Koroda, KCUA website

While working on the development of ‘async’, one of his last album releases before sadly passing in early 2023, Ryuichi Sakamoto spent a sweltering summer’s day at Kyoto City University of Arts, alone, playing and recording some of the restored Baschet Sound Sculpture instruments that had made such an impression on him as a teenager in 1970, with his remarkable creative life ahead of him.

Baschet Instrumentarium in the exhibition Baschet Sound Sculptures, Kyoto City University of Arts. 2020. photo: Tokeru Koroda, KCUA website

In the 1980s, Bernard developed the Baschet Instrumentarium, a set of 14 miniaturised instruments designed for childhood learning environments where kids can play together without needing skill or mastery, discovering sounds together. There are now over 500 of these in use worldwide, introducing new generations to the wonders of acoustic sound generation with unusual materials, creating multisensory experiences to continue inspiring young imaginations.

Further reading, viewing and listening

Baschet Sound Sculptures exhibition at the Kyoto City University of Arts 2020

Sachiko Nagata and Martí Ruids play restored Baschet Sound Sculptures from Osaka Expo’70

Association Structures Sonores Baschet – France

Dr Marti Ruids, University of Barcelona – Baschet blog

Hideyuki Doi plays the Ikedaphone after its restoration, 2009.

François Baschet recollections, translated from French to English