“The naming of the August blends points to a mood, an influence or a made-up world, and reflects the art director’s conviction that blending can be an art form.” From August Uncommon Tea

Ben Lignel interviews tea-blender Gina Zupsich about the gustatory and imaginary anchor points that underpin a powerful tea experience.

(A message to the reader in French.)

(A message to the reader in English.)

You sometimes receive a gift from dinner guests, who thus generously respond pre-emptively to the meal they are about to receive. And so, on the 15th September 2022, around 20:15, did tea entrepreneur and art director Gina Zupsich delicately drop a small pouch of “Low Country” and another of “Silent Night” in my lap, together with a tea-tasting booklet. “If you feel like it”, she said, “take note of what you taste”. The conversation that ensued over dinner hopscotched between news of the friend who’d put us in touch, and our shared interest in hospitality. But it most often veered towards the sensory world-creation that she has been engaging in for the past eight years, as art director of L.A.-based tea company August Uncommon Tea. Gina’s nomadic childhood, her fascination with both French culture and cuisine, her research into perfume, and a PhD in French Literature make her uniquely disposed to create unique blends, but also to reflect on tea’s changing cultural fortunes. In the following interview, conducted in January 2023, Gina talks about scents, flavors and moods, the engineered demise of tea within American public consciousness, and the work of understanding and celebrating tea’s infinite gustative range against the grain of popular perception.

The craft advocate that you are, dear reader, will recognize in Gina Zupsich’s aspirations aspects of craft advocacy that you are familiar with: in particular the push to bestow upon an immemorial, everyday, domestic practice the legitimacy of “art.” In craft as in tea blending, this ambition is caught up in a project of re-evaluating existing practices, and acquiring the language to describe their newfound meaningfulness. Gina’s work requires that she put moods, memories and tastes into words—words that expose others to the complexity of her creative ambitions, but also train them to taste how she does. The simple task of naming one’s practice has been challenging me from the day I started making jewelry, and is newly interesting as I train myself to make pots. To return to Gina, and perhaps contradict myself: I see in language a means to exit the semantic clutch of artspeak and imagine words and qualities that do justice to what is unique about one’s practice. Ezra Shales, the American scholar, did just this one day in class when he spoke about a Cherokee basket’s huggability.

✿

Ben: How did you learn to appreciate tea?

Gina: I first had tea and would have it regularly when I was a kid. No one made a big deal about it in my family because my mother drank a particular kind of tea called Constant Comment. I remember that smell. And I remember associating it with her sitting down taking some time to herself, and not when she was sick. It’s just something subtle. It was a black tea, and it had a very strong aroma…So I remember that. And then my paternal grandmother was ethnically Austrian. She grew up in the Austro-Hungarian empire and then became Slovenian, and then Yugoslavian. I don’t remember much coffee drinking happening in my grandparents’ house. All of their meals were very much about quality, enjoyment, pleasure, good taste. And my grandmother always made this apple tea, a black apple-flavored tea. She always served with those Danish butter cookies: I can picture the blue tin right now. I remember her saying, “Oh, would you like some tea?” There was no pressure; there was no fancy ritual. And you know, maybe we would chat, maybe we wouldn’t. That’s pretty much how I came to tea: it was just very normal.

Going to Paris, when I was 16, was an absolute culinary revelation to me. I was introduced to things I realized I enjoyed, things that I never thought I did. Like duck. And I realized it wasn’t what it was that made me like it. It was how it was cooked, it was how it was presented. I was allowed and invited to drink and eat everything. Coffee was offered, tea was offered, wine was offered. Cognac was offered. Of course, I took everything…I was like, great! At 16 I was sneaking cigarettes behind my parents’ back. And with my French host family, I was invited to have a cigarette on the leather couch, you know, with my espresso in the morning. It was fantastic.

And on one of my many trips to Paris, I had a friend who said, “Oh, have you been to Mariage Frères?” And I was like, “what’s that?” And she said, “Oh, you have to: you love perfume and you love food”. So we went to the rue du Bourg-Tibourg and entered the little apothecary there and I walked in and I remember just being like, wow, what is this place? It was like a temple of pleasure. I had never seen tea treated in this way. Like a precious commodity. Like an essential ritual. it was seductive to be in this environment when as soon as you walk into the room, you smell tons of tea.

Mariage was a very, very important turning point for me. Learning about tea and then having tea in the tea rooms there and having them serve me tea that was not in a tea bag. That was another revelation. Then somewhere along the line, I met Aaron. And Aaron’s cultural touchstone was Japan. And so he would say “the Japanese do this…and the Japanese do that.” At some point during my graduate study in Berkeley, I lived in a house with three other people. One of our roommates was a woman named Toshiko. And she’s from Kyoto and was teaching tea ceremony in the Urasenke school. And she invited me to my first tea ceremony. She explained to me the reason why there are different kinds of tea in Japan and she said, “we drink tea every day but it’s sencha not matcha”. She invited me to a spring tea ceremony. I learned from her that matcha is only ever consumed in Japan in these formal settings when you have a very intentional moment. And she said, “it’s usually based on the season”. Her job was not just to brew the tea—you know, to whisk it—but it was to present to everyone why we were all there. I was just mesmerized. She was becoming a pastry chef. We talked about flavor all the time, all the time: what are flavor affinities? Although Toshiko was part of a formal, traditional tea school, she was extremely open-minded about flavor and texture elements: she was very inspirational to me in that way.

Ben: Can you describe the sort of perceptions of tea you had to contend with, when you started August, the company you co-own with your partner Aaron? I was really interested by the tasting booklet you give your clients, and what comes across as an effort to train their taste buds: how you are trying to change how people think about a product that they’ve known for all their life.

Gina: Not everyone has had tea. And the lack of knowledge and experience with tea in the US is real. I became very aware of this just before we started our brand August. It was so surprising that I wrote an essay on perceptions of tea in the United States called “Does America hate tea?” But I never published it because I was worried about how it might impact our brand.

As an academic and someone who was working as a professor for over a decade, I do think about the different perceptions of tea from one culture to another. The more I talked to Americans about tea, the more I began to see connections in education because tea is not well understood even by the people who drink it. Americans drink a lot of tea for medicinal reasons, or they drink very traditional teas like English Breakfast or Earl Grey or basic black or green teas from major grocery brands. It’s mostly commodity tea as opposed to fine tea. Most of the tea market in the United States is bottled grocery store iced tea. What I do with respect to the August brand has been informed by my understanding of being American from an outsider perspective that comes from living abroad. I’ve always been influenced by European tastes, specifically food… Thinking about food, pleasure, and tea production, I want to touch on our tea partners. We work with tea vendors in Germany. The reason why we chose Germany instead of going to local US suppliers is because of a sense of pleasure and beauty in tea. There are tea blenders in the United States and there are tea importers. But when we compared the quality and variety of teas and blending capability, we went with a German company because they have an emphasis on pleasure, quality, and beauty in flavor.

In Europe there is a practice and a relationship to food, to meals and to cooking that is very, very pleasure-oriented, and there’s greater access to quality food than in the United States. I believe that the Slow Food Movement was an evolution of traditional European ways of eating: going to the grocery store or markets every other day, and buying what is needed for one to two days. Our practice in the United States is to shop a lot once or twice a month. Farmers’ Markets only became more prevalent in the past 15-20 years. Meanwhile, if we consider what happens in a lot of privileged American communities, there is a strong culture of food morality. I think especially in LA, there’s so much morality, and that this is a product of unacknowledged privilege and disparity in access to good food.

So if we just bring it back to attitudes towards tea in the United States: tea is not so much about pleasure now, though it was about pleasure back in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. In the late 17th century, there were three types of imported beverages in this country that are sometimes referred to as “drug drinks” because they all have stimulating effects. Tea was exclusive to the rich. There was coffee, which was also not very well known at the time, and finally there was cocoa. And the reason that tea took over was because tea was a drink that could be enjoyed diluted, and still made caloric and satisfying with milk and sugar. It was more economical for daily drinking than coffee or cocoa.

There is a unique, politically motivated rejection of tea in the United States, which is linked to the history of US tea importation. The rise in sugar production is related to the rise in tea importation and consumption by both Britain and America in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Tea, while naturally bitter, was made very palatable and caloric with sugar. It became not only a part of meals, but sometimes the meal itself for the laboring classes. It is thanks to the interdependence of tea and sugar that the British developed their two main colonial imports simultaneously: tea from India and sugar from the Caribbean and South America.

Tea was originally a wealthy privilege, which is true everywhere, including China. Tea was the drink of the religious, political, and social elite. And when you look at a lot of American antiques you see the importance of tea in tea cabinets and chests that were locked, because servants were paid part of their wages in tea.

Then there was an event which disrupted tea drinking culture in the US: the Boston Tea Party. Rich Americans who had acquired a taste for sugary tea eventually revolted against the excessive taxation of tea by the British. The dumping of tea into the harbor symbolizes a rejection of ongoing British power over America. So what I’m suggesting is that perhaps there is a collective unconscious feeling—initiated by the Boston tea Party—that drinking tea is un-American.

I’ll support this with my experience in talking about tea, especially in marketing tea to Americans today. Often the first thing people tell me when I offer them tea is that they either are a tea drinker or they are not. And sometimes the non tea drinker will proudly add, “I’m a coffee drinker”. Drinking tea or coffee to this day is very much a part of one’s identity in the United States. For example, tea lovers will tell me that they love tea because of ties to a strong tea-drinking culture, Britain, Ireland, Iran, Korea, China, and so on. There is not a continuous tradition of tea drinking in the US outside of these other cultural ties. That’s because just when tea drinking was on the rise in early America, major importation virtually stopped, at least, legally. With only illegally smuggled tea to enjoy, thirsty Americans turned to coffee, the other available sugary warm drink. Coffee was easily imported from neighboring Caribbean colonies. So tea was effectively supplanted by coffee as the most popular American hot drink in the wake of the Boston Tea Party. The substitution of coffee for tea did not happen anywhere else in the world. So Americans today love their coffee, but they don’t realize it was by design to substitute coffee for tea.

Ben: When we come to the 20th century, what happens? What are the different imaginaries that get overlaid over tea? What do your customers associate tea with?

Gina: In this country, tea is associated with sickness and medicine. Often people will tell me, “I finally had this tea that you gave me. I didn’t drink it until I got sick. And so I think to myself, that’s disheartening . I’m thinking, “So now when your tastebuds and your olfactory system are compromised, now you’re going to taste the tea? Thank you. Thank you for telling me that you’ve chosen this inopportune moment to experience this.” There’s usually no hint of embarrassment when someone tells me this. It’s kind of an unspoken understanding that tea is used as medicine, and not enjoyed like wine or coffee.

Ben: And Americans neither embrace the sophistication of continental tea drinkers, nor the “tea for every occasion” attitude I associate with the British?

Gina: Fine tea is not the biggest source of tea revenue in the US, despite the availability of quality traditional teas from everywhere including Japan, Taiwan, China, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and more from smaller tea-producing countries like South Korea and Thailand. From a medical standpoint, coffee is described as an excitant, and tea is identified as a stimulant, because it has an amino acid in it that actually slows the absorption of caffeine into the bloodstream. There is a very clear dichotomy in the US—at least right now—between coffee as coffee as drug and tea as medicine. And I think drugs are very exciting to people, so selling coffee as a daily drink isn’t as challenging as selling tea.

Ben: Can we speak about the different position that growers and blenders hold within tea culture? Are they necessarily separated activities, and is there more legitimacy to one of the two positions?

Gina: Good question. It’s important to mention that there’s a stigma today, particularly in the US, regarding flavored tea as a low quality product. In this way, August is definitely confronting a stigma of flavored tea worldwide, where tea flavoring has historically been done to cover low quality, or bad taste in tea. Despite this attitude towards flavored tea, the practice of flavoring tea is as old as tea itself. The history of tea in China has always included tea combined with other things, either for medicine or for pleasure. So this tension between pleasure and health of tea has always been part of tea history. Tea’s value as either more medicinal or more pleasurable depended very much on who was ruling emperor. And there’s one emperor in particular in China who made a distinction: Huizong, in the Song Dynasty (1082 – 1135). Huizong took an aesthetic interest in blending and flavoring. And the social practice in turn changed, to use tea not only as medicine, but also in an artistic combination with other plants, which would impart flavor, right like orange or citrus peels, dried flowers as well, Jasmine, chrysanthemum. Osmanthus is one of my favorites. Have you ever smelled it? It smells of apricots.

Some people make a distinction between scenting tea and flavoring tea. Smoking tea or adding naturally flavored ingredients like dried fruits, fruits, herbs, spices, etc, to impart flavor on the tea leaves is called “scenting”. It is a kind of infusion: tea blended with other plants. “Flavoring” tea is different because it is more like perfume: you are adding extractions or oils that are either natural or synthetic. Flavoring tea today is absolutely a European specialty. For example, Earl Grey is one of the best known flavored teas, which was created in England. Thinking about food, pleasure, and tea production, I want to talk about on our tea partners who are in Germany. The reason why we chose Germany instead of going to local US suppliers is because of a sense of pleasure and beauty in tea. We could have worked with US-based blenders and importers. But when we compared the quality and variety of teas and blending capability, we went with a German company because they have an emphasis on quality, modern flavoring, and aesthetics. .

Although blenders and tea producers do not have to be separate, they tend to be. I think it has everything to do with cultural preference. North Africans with French colonial influence drink more flavored teas. Russians also love flavored teas and scented teas.

Ben: What is your blending style? And what makes it so distinctive?

Gina: I always loved food and drink. I worked as a bartender for a long time. I’ve always been a good cook, and I’ve always learned from better cooks, including some professional chefs. I also happen to have a very strong scent memory. So when I began creating tea blends I learned that I have the ability to take flavor, or scent and make new blends like a picture. I can imagine them and combine flavors and scents like artists would use in painting: Tea blending for me is very much an artistic creative expression. I wanted to do something with tea that I saw happening with other culinary products, like with ice cream or cocktails, for example. And I only learned that I could do it by making a bunch of things, and then getting them actually produced. This is how I realized I’m like the “art director” for our tea.

Once Aaron said he would really like to have a tea that’s like a walk through a damp forest.

Let’s see if I can give you a good example…Once Aaron said he would really like to have a tea that’s like a walk through a damp forest. I thought what an interesting challenge. I was working with this base tea, which was really intense. And I thought, maybe this would do well in Russia or the Middle East, but I don’t think Americans would enjoy this. I wanted to do something very different… I don’t blend the things in my house but I do tinker with flavors. It is very chaotic and intuitive. The way it works is usually that I ask our team in Germany to actually produce samples based on my concept. I would tell them “put this and this ingredient or I want it to taste like this”. Sometimes I wouldn’t specify ingredients at all and instead I would say try to get to this flavor with a description, like the forest. And then we refine the blend together until it’s perfect.

Ben: Hold on… when you say “I want it to taste like this.” What are the words that you’re using? Are you describing an emotion? Are you describing an actual taste?

Gina: So, because I speak other languages, I know that we need to be very, very specific and tell our German vendors what type of “forest things” we want to taste. So I did add “truffle” in there. And I said, okay, we want it to taste very peaty, the opposite of muddy or earthy in which case they might choose a dirty-smelling fermented tea like puerh. We ended up with a tea that is black tea with some lapsang souchong and olive leaf, which has a truffle-like flavor, and then a lovely grilled banana to balance the earthy notes.

I learned about flavor vocabulary by doing it, but also just by eating and drinking: by going to restaurants and hearing them talk about the different tasting notes and going to wine schools in the Bordeaux region and in California, and taking notes on their elaborate descriptions with a great deal of nuance. I learned a lot about tea from the wine vocabulary: because, unlike coffee, but like wine, tea has so much more range.

Ben: Let’s go back to your blending style: can you point to some elements that make it distinctive?

Gina: I think we are one of the only tea companies to actually focus on the way tea feels in your mouth, the “mouthfeel”. This term is used a lot in the cocktail and wine world. Different teas have different sorts of feeling in your mouth. Some are more tannic and biting. Some are smoother and rounder, or more viscous. We use barley malt a lot, much to the chagrin of our gluten-intolerant customers. That’s because it has just the most amazing feel in the mouth. It’s silky. It’s rich. It’s wonderful. And you can imagine the Germans, making so much great beer and bread, are very good at sourcing good barley.

Ben: Do you see yourself as someone who influences the tastes of other people?

Gina: There are teas that people tell us have changed their lives or that they don’t taste like anything else. And that they are devoted to certain blends that they cannot imagine living without…People actually talk about our teas in those terms. And I love that. So those are our customers. They’re ready to get passionate about the way tea tastes and makes them feel. I am thrilled to know that I’m making things for people who are willing to take that leap into an unknown flavor, which is just an awesome sign of trust for me. I mean: I make these whimsical or wild things and for people to put in their bodies. It’s not like looking at a painting!

Ben: Let me clarify my question a bit. You remember when Henri Gault and Christian Millau introduced Nouvelle Cuisine in the 70s? They had very specific reasons for doing that. They were fighting against a practice of heavy creams and heavy overlays of flavors, and advocating for more discerning tastes. Does that match your own position within the tea culture?

Gina: I definitely do think there’s something there. The way that I want to influence people, first and foremost is to dissociate everything that they think, every reason why they like tea and like to drink it. I want people to let go of expectations and existing associations in order to just experience each tea in that moment. I want it to be an immediate experience. I do try to make a range of mild or simple to complex flavors. And undeniably, there are teas that I make that I personally do not like to drink, but I make them because I know that there’s a place for people to really be passionate about that flavor. My bias is in unexpected combinations.

Ben: Would you ever do a tea that wasn’t premised on the connection between memory and pleasure…a tea that was trying to be futuristic in the strict sense of the word?

Gina: Yeah, I mean, that brings a couple of things to mind. I have done a couple of teas that they’re not necessarily futuristic, but they’re fantasy oriented. One of them is called “Cocteau”. And a lot of Americans have no idea who Cocteau is but it’s also referring to the Cocteau Twins, and more Americans know who they are. At least Gen Xers do. It’s one of my favorite stories about a blend that we have. Aaron had made a spreadsheet, which horrifies me because I don’t like to constrain myself. But he said “okay, you have to specify all of the ingredients and the tea directions”. So what I wrote was earthy rooibos with honey, vanilla, peppermint, and grapefruit…I specified every single ingredient and they were about five And when I was finished Aaron looked at it, and he said, “Whoa there’s way too many ingredients in here”. And I said, “Excuse me, I’m the one who’s directing the flavor here”. And he said, “Well, I just think it’d be a waste of time because it’s not going to taste good”. And I said, “Okay, well, you know what, let’s just have them make a sample and see what it tastes like when we get a sample”.

And it was absolutely divine. And as I was drinking, I realized that in each sip, it takes on a new new flavor. One sip, it will taste more earthy, next it will be more grapefruit, the next it will be more vanilla, the next will be more mint. And they’re sort of interchanging and that’s why I named it Cocteau. Both for the Cocteau Twins, and for Cocteau himself, because there was this sort of beautiful swirling and fuzziness to it where some ingredients would pop out and then go good back into the background. Both Jean Cocteau and the Cocteau Twins broke aesthetic rules. The singer even sang in a made up language. And this flavor really felt like what people in the cocktail world describe as “structured”: there was a place for each thing. And there was a dynamic to the flavor itself, which I loved. It’s definitely not one of our best selling teas. But to me that was really pushing into more of a fringe sort of taste preference.

Ben: Do your customers ever request pure teas?

Gina: I think there’s a movement in the coffee world, to be very focused on the source, very focused on a farm. And then the processing of coffee will “finish it” in different ways. People don’t source tea and then finish the tea leaves themselves away from the tea estates, as they do with coffee beans and roasting.

Ben: I think it is super interesting: while coffee lends itself to sort of adulation of provenance, and then a sort of fascination with the ritual of brewing, perhaps tea doesn’t lend itself to that and therefore generates a different sort of expertise…that goes in different direction?

Gina: Yeah, one of the things that I have noticed when we do a tasting with cafe owners who specialize in third wave coffee, is that they may enjoy the flavors of tea that we produce… But they will always start asking us questions about pure teas. And pure teas are wonderful…but they require a level of education and sophistication of the palate to even taste those subtle flavors. Based on the average American diet, and general preference for extreme flavors, most Americans are not going to be able to appreciate a fine Darjeeling or, you know, like different flushes and different mountain elevations of oolongs, etcera.

Ben: Still, you could have decided to do go in that direction.

Gina: We could have, but it would not have been as exciting for me as an artist. It would not have been the same. Because I would really be curating, I would say, “Okay, I prefer the taste of this particular tea”. There’s a problem with consistency and availability, too, because like any agricultural product, there is a lot of room for variation from crop to crop. The creative force there is nature. The creativity would happen for someone else growing, harvesting, and finishing the tea. And I would love to be able to showcase these beautiful teas, but to date, they have never sold well for Americans. I think it takes a particular interest to develop your palate. For any type of drink, or food, you really have to train your senses. The cool thing is that it’s absolutely possible to train your nose and your palate…

Ben: Speaking about training… you’ve been in business for nine years now: Do you find that your clients now have learned a “tea language”? Do they now enjoy your teas differently?

I like to give people anchors for flavor and feeling

Gina: Yeah, I think so. There are a lot of different forces at work, but exposure is a kind of education. So simply by presenting people with teas with different ingredients. I create tasting notes, but I also create mood notes that are printed on the package of each tea blend. Because I think that these descriptions appeal to different kinds of people in different ways. I’ll give you an example of a tea that’s about to be released, and I’m actually very excited about this. And my hope is that people will respond in the way that I did. it’s a coffee-alternative tea. So there’s no coffee in it, and it’s caffeine free. It’s mainly a grain and root tea. There’s chicory and barley. And there’s some cacao and some reishi mushroom. When I first brewed it I was in love with the smell. It smells like walking into a county fair with the smell of fresh hot kettle corn wafting into the warm summer air. And so I write these notes down, and I say okay, kettle corn and hot butter. And I like to give people anchors for flavor and feeling. But for me, there’s a kind of synesthesia that happens with flavor. And I think that more people feel this than they can articulate or they are conscious of. When I tell people this tea “tastes like hot buttered popcorn”… they’ll say “okay, that’s kind of weird”. And maybe they’re thinking of a movie theater from their childhood or something. But if I say it, “it’s going to make you feel like you’re walking into the county fair, and it’s a hot summer day”. And all of a sudden, there’s so much more emotion and immediate connection. And a lot of things are potentially happening at once. Maybe someone is imagining the smell of barnyard animals, or who knows what other county fair smells, and also them smell of hot popcorn and hot roasted corn and cotton candy.

I do give people sensory anchors because I don’t want to tell anyone what to taste. At the same time, I want to tell them what I taste and what they can look for. It’s up to them to notice their own taste and feeling. I love seeing all of the reviews of our teas published because it is such honest feedback about what people feel and what they taste. And I think it’s very hard to separate what someone tastes and how the taste makes them feel. I think it’s very hard.

Ben: I can see different ways in which you’re laying the ground for people to think about their tea experience in a certain way. You’re using imaginaries that are very varied, some of which are highly sophisticated, others are pop-cultural. You think about teas in the same way that a chef would think about creating a meal or creating a dish: as a multi–tiered cultural construction.

Gina: I sometimes feel like people think that they need to be practicing Buddhists to enjoy certain types of tea. For me, that’s not necessary. If I’m trying to educate anyone in any way, it’s to free themselves to have an immediate flavor experience with something: to really just close their eyes and not worry about the steps in the proper tea tasting, or having to use certain China or do you use milk first or do you use the tea first? Or do you use milk at all?

I don’t think these things are as important as the immediate experience of something that can simply create a feeling for you, you know, a feeling of pleasure….

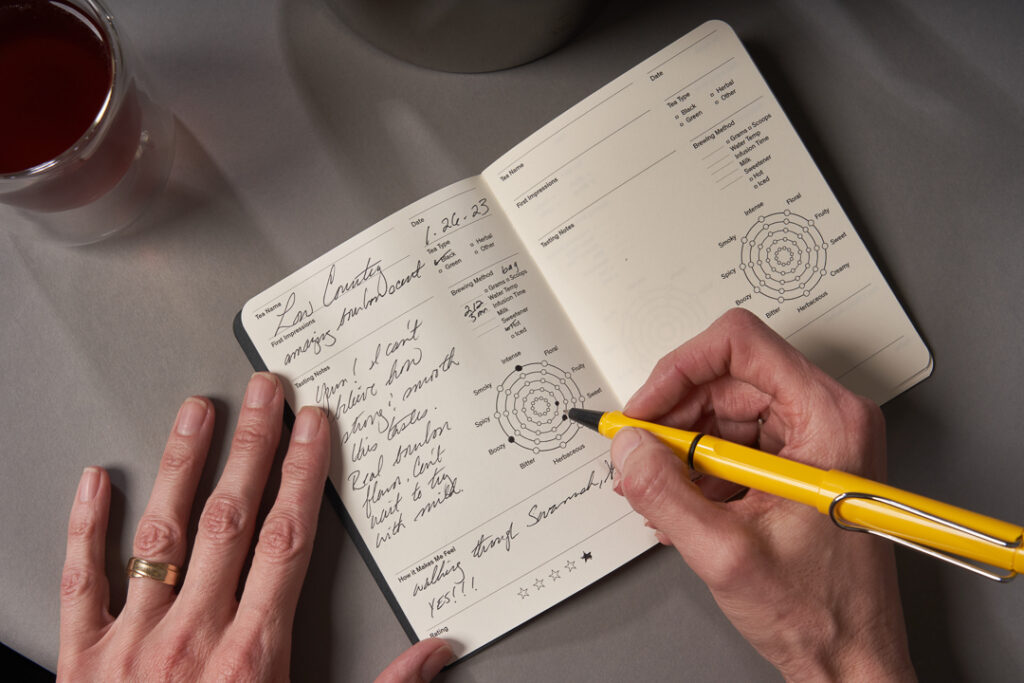

The tasting booklet that accompanies August’s teas encourages customers to train their palate, and develop a language around their experience of tea; photo: Aaron Shinn

Ben: We haven’t spoken so much about the making of things or the trying things out. Is there a moment in that process where you try things out?

Gina: Earlier I talked about this particular forest floor tea that Aaron really wanted to have. It’s a very abstract way of crafting flavor. But we got a sample and as I mentioned, it tasted too savory to me. I didn’t think that this was something that Americans would enjoy. So here we had this savory, foresty tea that had a little bit of smoke tea, and another black tea and olive leaf which is very sort of sharp and high frequency and its flavor. And I wanted to find that last perfect harmonizing note, and I couldn’t figure it out. And I said, Okay, it’s got to be a counterpoint. It probably should be sweet -not too sweet, but a little bit sweet. So I actually had the base tea blend, and we had versions of it that had more smoked tea or less smoke tea, or more olive leaf or less. I was playing with these variations. And I chose the one that I liked the best. I had it in my hand and I was just in my kitchen, “How can I go about doing this without wasting another several weeks?” And I thought all right, it has to be a deep, sweet flavor. I had some like cocoa powder and pick that up. And I was like, Okay… maybe dark cocoa or cocoa nibs could be good because they’re kind of sweet. But there is a round bitterness to the cacao nib itself. And then I don’t know…I’m not a big fan of banana at all, but I have found banana to be really awesome with tea because it’s a natural ingredient that imparts beautiful flavor and sweetness naturally, and the thing I love the most about bananas is their floral quality. They’re much more complex than anyone would think. I happened to have some banana chips around, and I kept smelling back and forth like “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, banana. Okay, let’s try this.” So we sent out and I asked for cacao, and then I asked for banana and I was like, I don’t know, maybe the banana will work, maybe it won’t. So we got it back and Aaron and I tasted all … looking for that last perfect tea and we both agree like “It’s banana!” Banana creates a perfect balance. These woodsy piney flavors, with the olive leaf and a smoky banana. It became our smoky banana tea and it’s called “the Black Lodge” named in part after Twin Peaks. People went crazy for that. It’s definitely a cult classic and it has when you brew it, it’s actually quite mild because there’s a lot of non-tea in it. But then the banana really makes it sing: it ends up tasting a little bit like a kind of a percolator coffee, like a weak percolator coffee, which is very nice.

Ben: In our conversation, although we have often discussed “the French” or The Americans”, you really are most at home making up very granular and layered imaginaries: Can you speak about that tension?”

Gina: Well, it has to do with my experience with both cultures: I grew up moving all around the United States. As far as flavor I am very inspired by both France and the United States. All of what I eat during my travels or at home inspires me.

But I think what happens for me—and I think what happens with August customers—is that it is actually liberation of flavor from cultural ties. So while I will create a cultural touchpoint with a description or name or mood, it’s only an anchor. I have to go back to “Low Country” tea for a moment: The Lowcountry is along the coast of Georgia, and a little bit of South Carolina, and I have been delighted to have people say “I’m from the Lowcountry and this reminds me of home because of these flavors”. It’s evocative because there are buckwheat flavors. And there are different sorts of roots like chicory and richness that offset the high-pitched sharpness of bourbon, which is not made in Georgia, but really close by…So I’m not always literal. I just want to be playful about it. For me, it’s much more an adventure of travel: being evocative is much more interesting to me than actually making cultural distinctions and saying, well as, as a person from this community, you would appreciate this. Using cultural references whether geographic or musical or artistic, for me, is another way to articulate things that people may or may not relate to.

Ben: I’m interested in how the making and the selling of tea is a venture that traditionally needs to position its target audience at a remove from the place where things are produced, as the British have in relation to Indian tea, by exoticizing the place of production. You’re not doing that: instead you are creating evocative blends which in some cases are mixed to the point where it can’t be from one place. Similarly, there’s very little in your package that speaks about harvesting. Nor are you promoting your German suppliers. Instead, your narrative is all about the imaginary that you put together, as a dish or a painting, to use your own metaphors.

Gina: Yeah, I mean, I think flavor is very emotional. And a lot of people don’t realize that it is emotional. When we crave something there’s usually an emotion behind it. And I think that there is emotion created when we eat things, also. To go back to the book that you mentioned: our tea tasting guide is really about attunement to your senses. And about pointing out the different sensual encounters or points of encounter that you have with tea from looking at the package, reading the name, reading the mood notes, opening the tea, looking at the leaves, smelling the dry leaf, and then brewing the tea, appreciating the aroma of the tea brewing, or anticipation that creates and then finally there is the flavor. Take one or two sips. Next do you add milk? What happens then? Do you ice it? What happens then? I would like everything to be very accessible. But truly, it’s just an invitation to an experience that hopefully is very pleasurable and exciting.

It’s funny, even using the word pleasure …We haven’t emphasized that word very much in our brand because pleasure to most Americans reads as sexual or erotic, and it’s very much not okay in marketing to the general public. So I tried to emphasize adventure, because I do think that there’s a lot of possibility for excitement that can be pleasurable without, you know potentially, triggering people.

Ben: Is there a question that I didn’t ask you that I should have asked? Something that should be known which hasn’t been discussed today?

Gina: That’s a good question. Is there something that should be known? The entire world is very caught up in tea as a tradition. I really do think that tea itself is something that really struggles to be brought into modern culinary realms. It sits in the annals of history as something that is part of a tradition, that has always been there, and that we can’t touch …maybe it is taboo to do something to tea. And one of the things that I have been trying to do with August is to liberate tea as something that can be just playful. It’s just another area that we can explore as an art form, or as a fun activity.

About Ben Lignel

Ben Lignel is a craft thinker, educator, and maker living in Montreuil, the town of which Paris is the suburb. He works in flameware and porcelain, and makes objects for cooking and hosting with. They will be on show at the upcoming Paris Ceramic Festival, 14-16 April 2023. His experiments with steam, stews and stirs can be seen on @benlignel. Portrait photo by Baptiste Lignel / Otra Vista.

Ben Lignel is a craft thinker, educator, and maker living in Montreuil, the town of which Paris is the suburb. He works in flameware and porcelain, and makes objects for cooking and hosting with. They will be on show at the upcoming Paris Ceramic Festival, 14-16 April 2023. His experiments with steam, stews and stirs can be seen on @benlignel. Portrait photo by Baptiste Lignel / Otra Vista.