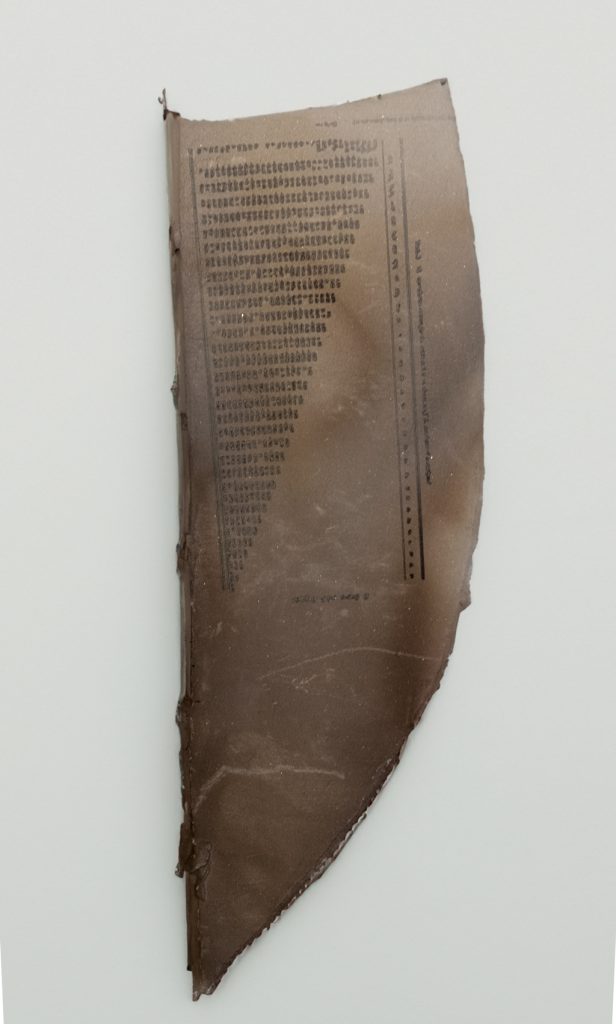

- Guillaume Slizewicz, Fragmented memories, 2025, clay and aluminum

Using data visualisation, Guillaume Slizewicz re-embodies archaeology back into clay fragments.

In the medieval hall of Holland College in Leuven, ceramic tiles hang suspended from aluminium frames. Visitors pause, their expressions shifting as they place these objects in time. Ancient fragments? Contemporary art? Scientific diagrams?

These tiles exist at the intersection of time periods. Their surfaces bear patterns inscribed by robotic arms following algorithmic instructions, yet fired using techniques perfected millennia ago

The Archaeology of Knowledge

“Fragmented Memories” began with an encounter with Professor Patrick Degryse’s archaeological research through the Parallax exhibition at KU Leuven. Particularly, his Caribbean ceramics research. Through geochemical analysis, he traces how indigenous pottery traditions responded to European colonization in the Dominican Republic. For instance, he lays out evidence that indigenous potters continued using traditional clay sources and techniques even after colonial contact. We could see that as a form of quiet resistance preserved in the minerals of their vessels. But his work captivated me not for its scientific conclusions, but for its visual language. The images in his papers possess a strange beauty entirely separate from their scientific purpose. Micrographs showing crystalline structures, spectroscopic analyses, and composition charts become increasingly abstract as one moves deeper into specialized visualization. Cross-sections of simple pottery fragments, viewed under polarized light, transform into something cosmic, mineral constellations trapped in clay.

Approaching scientific papers from outside the discipline brings a particular kind of attention. Without training in archaeometry, certain aspects remain at the periphery of comprehension. This partial understanding provides a different perspective and reveals patterns and connections perhaps invisible to specialists immersed in their methodologies. There is a certain pleasure in this liminal position, this standing at the threshold of knowledge domains. It recalls the archaeologist’s position when encountering artifacts whose purposes can only be partially reconstructed. By transferring scientific diagrams onto clay, questions emerge about knowledge itself. How does understanding persist through materials? What survives when cultures clash? Which forms of knowing exist outside of written records?

Ceramics

- Guillaume Slizewicz, Fragmented memories, 2025, clay and aluminum

The question of technological displacement arises frequently in discussions of contemporary craft. This framing often seems insufficient. In the studio, machines function not as replacements but as extensions of human intention, as a continuation of a dialogue between maker and material that has persisted for millennia. When a robotic arm inscribes patterns on clay, it explores how new tools might become part of ancient material practices rather than rejecting tradition. Working with ceramics places one within one of humanity’s oldest continuous technological traditions. The transformation of clay through fire has persisted for at least twenty millennia, thus predating agriculture. Any contribution to this lineage remains necessarily modest.

Working with ceramic artist Lena Babinet, we transferred Patrick Degryse’s visualizations onto clay using ancient techniques: sigilée (extremely fine clay slip) and sgraffito (incising through coloured layers). For the final firing, a small ritual was performed: burning the actual academic papers to generate smoke for the ceramic firing. The scholarly work, with all its careful analysis, became carbon traces embedded in the clay. During the exhibition dialogue, Professor Degryse remarked on the ritual dimension of knowledge transmission: “There is a difference between the functional and the ritual… what humans do strictly for functional purposes versus the ritual, the learning, the master-apprentice relationship and how human knowledge evolves.” His observation illuminates the central question underlying his Caribbean ceramic research: how certain techniques persisted after colonial contact, not merely as functional choices but as embodied cultural knowledge. The rituals of making carried memory in the absence of written records.

The Persistence of Ritual and Material Memory

In “Fragmented Memories,” the burning of academic papers to generate smoke for ceramic firing transforms specialized knowledge into sensory experience. The academic texts, which are the product of empirical methodology and analytical thought, become elemental components absorbed into the clay body. Knowledge completes a circuit from matter to abstraction and back to matter.

These ceramic works don’t reject digital processes but rather ground them, bringing algorithms into conversation with five thousand years of material tradition.

As our digital world accelerates and information grows increasingly ephemeral, working with clay feels almost rebellious. It remains one of humanity’s oldest and most durable recording media; ceramic tablets from ancient Mesopotamia are perfectly legible while files from ten years ago languish on unreadable disks. These ceramic works don’t reject digital processes but rather ground them, bringing algorithms into conversation with five thousand years of material tradition. These objects exist in multiple time frames at once and connect prehistoric standing stones with neural networks, indigenous pottery traditions with data visualization, and academic papers with smoke-fired clay. The tiles in “Fragmented Memories,” with their machine-inscribed patterns and traces of burnt academic papers, suggest a continuity rather than a rupture, where algorithm and artifact, science and ritual aren’t opposites but complementary aspects of human creativity. They quietly ask which of our knowledge will actually endure, and which will vanish without a trace.

About Guillaume Slizewicz

Graduating in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics from the University of Kent and later in Production Technology at Copenhagen’s School of Design and Technology, Guillaume founded his studio in 2021 to explore these relationships through digital arts and collectible design. His works often blend physical materials—metal, wood, and clay—with digital processes like algorithms, artificial intelligence, and computer-aided manufacturing. Guillaume’s artistic inquiry extends beyond materials to his collaborative and experimental methodology. His works, often developed within collectives and with other designers, connect the past with the future, linking craftsmanship with computational processes. His work has been presented by institutions like MAD(Brussels), Impakt (Utrecht), Design Museum (Ghent), Le Pavillon (Namur), BioArt Labs (Eindhoven), Fake/Authentic (Milan) by universities in Brussels, Leuven, Basel, Trier and Hong Kong, as well as in grassroots venues deep in the local urban fabric such Biestebroekbis, La Maison du Livre St Gilles and Constant in Brussels. Recent exhibitions include Glazed Grandeur in the framework of “Art Nouveau as a new EUtopia in Darvas House, Oradea, Romania”, starting the 8th of June 2025- “Duo en Résonance”, Maison Hannon, Brussels, starting on the 7th of June 2025, and “Crossing Wires — Arts, AI & Robotics” 26-28 May 2025.

Graduating in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics from the University of Kent and later in Production Technology at Copenhagen’s School of Design and Technology, Guillaume founded his studio in 2021 to explore these relationships through digital arts and collectible design. His works often blend physical materials—metal, wood, and clay—with digital processes like algorithms, artificial intelligence, and computer-aided manufacturing. Guillaume’s artistic inquiry extends beyond materials to his collaborative and experimental methodology. His works, often developed within collectives and with other designers, connect the past with the future, linking craftsmanship with computational processes. His work has been presented by institutions like MAD(Brussels), Impakt (Utrecht), Design Museum (Ghent), Le Pavillon (Namur), BioArt Labs (Eindhoven), Fake/Authentic (Milan) by universities in Brussels, Leuven, Basel, Trier and Hong Kong, as well as in grassroots venues deep in the local urban fabric such Biestebroekbis, La Maison du Livre St Gilles and Constant in Brussels. Recent exhibitions include Glazed Grandeur in the framework of “Art Nouveau as a new EUtopia in Darvas House, Oradea, Romania”, starting the 8th of June 2025- “Duo en Résonance”, Maison Hannon, Brussels, starting on the 7th of June 2025, and “Crossing Wires — Arts, AI & Robotics” 26-28 May 2025.