Frida Kahlo, “Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States,” 1932, oil on metal, collection Maria Rodriguez de Reyero

When making a creative statement, visual artists often engage the imagination but also try to bring into focus the real-world references and advocacy behind the art. One important reference point (since the beginning of the millennium) is what some activists and scholars call transmigration, the back-and-forth tug of physical, mental and emotional migration between places, as with Latin Americans who have migrated to the northern areas of North America or el norte. Amongst the first twentieth-century Mexican artists to attempt to capture visually the experience and topographical mien of transmigration was Frida Kahlo.

A 2008 New York Times article by Arthur Lurow, After Frida (Después de Frida), surveyed the state of Latin American art at the time, focusing on outspoken Houston-based curator Mari Carmen Ramirez and her goal of expanding general knowledge of Latin American art. Lurow wrote that Ramirez objected to “the phenomenon of Frida Kahlo and the way it obscures Latin American art” and the presentation of Kahlo to the public “as an emblem for entire continents.” Ramirez believed that Kahlo was not a technically good painter and argued that it was important to recognize other artistic movements across Latin America, in particular, late modern South American art widely manifested in the early 1950s around the time of Kahlo’s death.

It’s now 2018 and the world has changed. The current U.S. Administration has enacted policies to limit immigration and is bullying immigrant populations. They want a literal physical wall along the México/U.S. border to keep Mexicans and others away, destroying a human and natural ecosystem that has existed since before 1848, when the U.S. Southwest was Mexican territory. But who is being kept out, and why now? It’s time for a re-look at Ramirez’s critique of Kahlo, an artist who embarked on an early manifestation of transmigrant creativity. Today, Kahlo’s artwork and life experiences can elucidate another aspect of the México/United States “border problem.”

Three years before Lurow’s article, the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico presented an exhibit titled Frida Kahlo: y Sus Mundos/and Her Worlds. The exhibition catalogue essay by art historian Andrea Kettenmann began with Kahlo’s 1932 painting, Autoretrato en la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos (Self-Portrait on the Border between México and the United States). It was painted at a time when Kahlo was periodically accompanying her muralist husband, Diego Rivera, to the United States. Kettenmann described Kahlo’s 1932 self-portrait: “In an elegant pink gown and holding a Mexican flag in her left hand, she rises like a statue on a pedestal before a world divided in two: the Mexican world, pregnant with history under the sway of powers of nature and life cycle, and the world of the United States, dominated by technique.” (Fig. 1)

Ramirez missed the fact that Kahlo, with this painting and others, visualized a transmigrant experience of constant travels between two countries, an artistic feat that was pioneering and thought-provoking for both Mexicans in exile and non-European migrants in search of the “American Dream.”

Almost a century after Kahlo produced that portrait, the borderlands is still a place of inspiration, mystique, danger and political disorder not just for artists, but for border town families, governments, international businesses and nacro-trafficking. Superseding Kahlo’s artistic legacy, more and more artists have been drawn to depict their own experiences travelling through, being an exile or living near the border.

Since the Chicano (Mexican American) civil rights movement or El Movimiento of the 1960s-1970s, hundreds of important Chicana/o (Chicana and Chicano) and Mexican artists like David Avalos, Rupert Garcia, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Graciela Iturbide, Yolanda López, Adolfo Patiño, etc. have assembled pioneering 1970s-1980s bodies of work focused on the border. Like Kahlo and these aforementioned artists, significant artists of the now modern era have brought to their production the “human aspect,” drawing on their own personal experiences as an integral part of their work.

Border studies scholarship can speak of “closed borders”, “open borders” or “porous borders”, but in terms of artistic expression, one may also speak of “border poetics” explored by Mexican and U.S. artists illustrating the borderlands and or the migratory experience. Chicana/o and Mexican artists Celia Álvarez-Muñoz, Minerva Cuevas, César Damián, Maria de Los Angeles, Delilah Montoya and myself have worked with this topic (for some of these artists it has been close to 30 years of cultural production). Their approach distinguishes them from many other Chicana/o and Mexican artists by their conceptual frameworks for advocacy, involving new media as well as social media, which positions their work onto broader audiences. This essay surveys significant border-themed works from their cultural production from the start of the millennia to now.

Celia Álvarez-Muñoz’s Fibra y Furia (Fiber and Fury): Exploitation is in Vogue (1996-2003) and Delilah Montoya’s Sed: The Trail of Thirst (2004-2008), come to mind. Both artists are of Mexican descent, born and residing close to the Chihuahua/Texas border. Álvarez-Muñoz’s Fibra y Furia (Fiber and Fury): Exploitation is in Vogue is amongst the first creative responses by activists and scholars to femicides—the abductions and murders of exploited Mexican women travelling to and from the borderland factories where they worked for foreign investors and international businesses.

In a 2006 essay, art historian, Asta M. Kuusinen points out the historical references that Álvarez-Muñoz’s work suggest upon her first viewing as “a mistake to think that this was something new, an unexpected upshot of the 1994 ratification of NAFTA”, a free trade agreement between Canada, and the U.S., Kuusinen is stressing that the series represents a “super-exploitation” of Mexican women labour going back to “the period of Spanish colonization, indigenous women” who were “raped and forced to work as servants in mining camps, missions, and military bases.”

- Celia Álvarez Muñoz’s Fibra y Furia (Fiber and Fury): Exploitation is in Vogue, detail of the “sequined crotch” work in its first 1999 exhibit installation at the Irving Art Center (Irving, U.S.A.). Photo credits: Celia Álvarez Muñoz. Courtesy of Celia Álvarez Muñoz.

- Celia Álvarez Muñoz’s Fibra y Furia (Fiber and Fury): Exploitation is in Vogue, an installation view of the “sequined crotch” works in its 1999 exhibit venue at the Irving Art Center (Irving, U.S.A.). Photo credits: Celia Álvarez Muñoz. Courtesy of Celia Álvarez Muñoz.

In the work, Álvarez-Muñoz referred to the missing and murdered women around the Ciudad Juarez area as the desaparecidas (disappeared ones). The Fibra y Furia (Fiber and Fury): Exploitation is in Vogue installation consisted of mixed-media photography alongside fibre structures, presented in variable sizes or mounted as installation projects within mostly gallery and museum settings. Since the late 1990s, Álvarez-Muñoz’s presentations have evolved into sexually-charged sculptural forms such as suspended hangings of embellished women’s clothing or “sequined crotch” as refer by Álvarez-Muñoz.

Delilah Montoya, Sed: Trail of Thirst-Humane Borders Water Station 2004, 2008, diebond mount, A/P, 18 inches x 45.5 inches, ink jet on E-Satin. Collection of the National Museum of Mexican Art. Courtesy of Delilah Montoya.

Montoya’s transmedia initiated and research-based Sed: The Trail of Thirst, completed in collaboration with activist/artist Orlando Lara, investigates the undocumented deaths of migrants attempting to cross the borderland desert in search of a better life. The digital photographic/video documentation focused on the Sonora/Arizona border. The imagery referenced the physical landscape and contrasted the humanitarians who set up fresh water stations to sustain travellers and the paramilitary-style groups that destroy the water repositories. Art critic Ken Johnson commented that: ”Without the works’ titles, you would not know that Delilah Montoya’s wide-angle landscape photographs depict stopping places” and added that Montoya turns “ugly subjects into beautiful pictures.” Montoya’s further evolution, production and research led to her awareness of the concerns belonging to the bordering Mexican/U.S. indigenous communities.

- Minerva Cuevas interacting with the physical environment of the Rio Bravo area, in creating a body of work entitled: Crossing the Rio Bravo (2010-2011) performance action, string, lime, water, brush, metallic bucket, pavement paint, rocks, compass, and flowers. Courtesy of Minerva Cuevas & kurimanzutto.

- Minerva Cuevas, Crossing the Rio Bravo, (2010-2011) performance action, string, lime, water, brush, metallic bucket, pavement paint, rocks, compass, and flowers. Courtesy of Minerva Cuevas & kurimanzutto

- Installation view of Crossing the Rio Bravo in the 2011 exhibit, Resisting the Present at Musée d’ art moderne de la Ville de Paris-ARC (Paris, France). Courtesy of Minerva Cuevas & kurimanzutto.

- Installation views of César Damián’s Memoria y Migración series. Photo credit: David Barbour. Courtesy of César Damián.

Internationally renowned Mexico City-based artist, Minerva Cuevas has once explored the topic of the borderlands. In 2010, Cuevas made a thoughtful performance, Crossing the Rio Bravo (2010-2011). In a rock-strewn, shallow portion of the river, she painted white lines on the river rocks to physically mark a border crossing between México’s Chihuahuan desert and Texas. Her work subverts the subcultural narrative of border violence constructed by U.S. media culture, “fake news” and the human confrontation with the bordering landscape. The execution of this action-based performance (documented digitally) morphed into installation works with collected objects and digital photographs referencing the Rio Bravo’s historical timeline.

- Celia Álvarez Muñoz. Fury/Furia, 1999, lambda photo print, 60 in. x 40 in.; photo: Celia Álvarez Muñoz. Courtesy of Celia Álvarez Muñoz.

- Detail of César Damián’s Memoria y Migración series. Courtesy of César Damián.

Then during an artist residency in Canada, Michoacan-based artist César Damián realised a project titled Memoria y Migración (Memory and Migration), which documents his obsession with the topic of migration. A Mexican who has no migrant family in the U.S., he sought to experience transmigration and being treated as an undocumented person. He started to create site-specific installations of portraits placed in lighted glass jars set in swing-animated motion, creating darkened gallery rooms of hanging, moving glowing structures. In a statement, he claimed to be presenting a “fantasy” of “the American Dream, which at the same time is the cultural mirage” for “entire groups of people.” This particular body of work has been presented in varied formats, all involved new media technology in Canada, U.S. and in México.

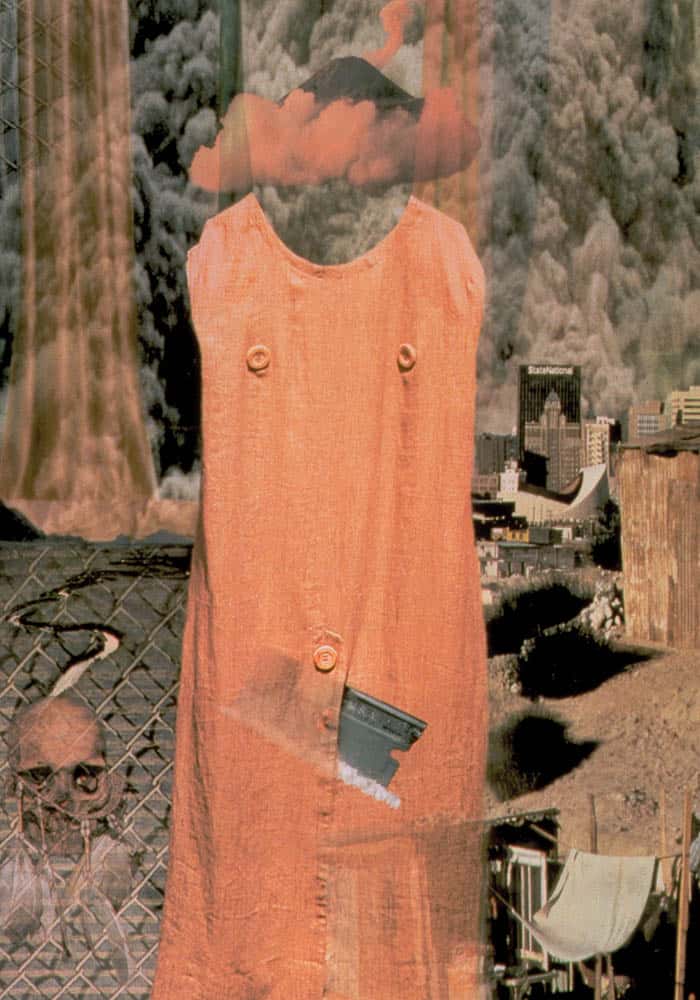

Jesús Macarena-Ávila, Callejera (Streetwalker), digital photograph, clothes, 48 inches x 36 inches, ink jet on photo paper, 2009. Courtesy of Jesús Macarena-Ávila.

From a U.S. Midwestern perspective, my 2008-2010 digital documentation uses material culture such as clothes to discuss border issues, from transmigration to recent family detention camps in the Texan border towns. Digital works such as Callejera (Streetwalker) interrogate a transmigrant journey, visualizing what one does or takes on this journey. Then in 2017, my series, Mi Madre/My Mother: Ordinary Women/Extraordinary Stories (2017-2018) consisted of portraits of immigrant mothers and their offspring (Latin American and other country origins) with superimposed quotes to suggest internet memes. These portraits function as a community-engaged statement on the importance of keeping families together.

- In Notre Dame, Indiana, Mi Madre/My Mother: Ordinary Women/Extraordinary Stories opened at the Galería América on the University of Notre Dame campus and was on display from October 2017 until January 2018. Courtesy of Jesús Macarena-Ávila.

- Jesús Macarena-Ávila, Babyjails, digital collage, 25 inches x 20.5 inches, ink jet on photo paper, 2017-2018. Courtesy of Jesús Macarena-Ávila.

The series was displayed in several Midwest venues including the Galería América located on the University of Notre Dame campus with an essay by noted Chicano art historian, Víctor A. Sorell. He states in the exhibit’s brochure that these community portraits cut “deeply into our collective consciousness with a sharp sociological edge” and its “subjects are redolent with the fragrant bouquet of a triumphant motherhood against the rot of a despotic immigration agenda.” One digital collage interconnected with this series, Babyjails (2017-2018), juxtaposes a Google Maps image of a U.S. detention camp for undocumented youth with the super-imposed word “Babyjails”, a term used by activists and lawyers in defending detained and separated families.

The last surveyed artist, Maria de Los Angeles, a recent MFA graduate from Yale University has been presently an advocate on the U.S.’s Eastern coast and on social media for immigration rights, since she is a DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program, initiated by the prior U.S. administration) recipient. In a recent interview, de Los Angeles states that the work originates from her “experience and knowledge about the border that came… from friends, family and the news.” She, as a child migrated to northern California from the borderlands of Baja California Norte/Sonora/California in 2000.

- Maria de Los Angeles standing in the center of her work, Citizen Installation (2016-2017) at El Museo del Barrio (New York City, U.S.A.) that resulted from the museum’s Be Back in 5 Minutes Residency. Photo credit: Cheyenne Coleman. Courtesy of Maria de Los Angeles.

- Detail of Citizen Installation (2016-2017) by Maria de Los Angeles. Courtesy of Maria de Los Angeles.

Her artistic practice has been influenced by similar storytelling traditions that Kahlo used. As seen with her installation work, Citizen Installation (2016-2017) which incorporates naive-styled imagery (within a room of 300 drawings on paper and including imagery drawn onto dresses, modelled by free-standing mannequins). Its fictional and personal narratives illustrate childhood memories leading to young adult experiences of living by the borders and now, living in between the states of New Jersey and New York. She states that the paper dresses are “meant to represent an iconic or idealized Mexican self… it does reference Frida but also Mesoamerican culture and Spanish culture.” The references of paper suggest an “identity… as a Mexican who grew up in the states without ability to travel to Mexico.”

Confronting the border complex in contemporary Mexican and U.S. artistic expressions remains vitally important. Kahlo’s Autoretrato en la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos stands in a long trajectory of artists on both sides of the border reminding us that human factors are tied to México/United States borderland issues. Border-themed art reaches out, expressing compassion about transmigrant experiences and examining, melting and shrinking national borders, now within a digital matrix full of hypertext, filtered selfies, Youtube videos and pixelated lives.

For further reading and border-themed art

Border Angels: The Power of One, 2015

Culture Across Borders: Mexican Immigration and Popular Culture, 1998

Frida Kahlo and Her Worlds; Y Sus Mundos, 2005

Música Sin Fronteras: Ensayos Sobre Migración, Música e Identidad, 2009

Minerva Cuevas’s border performance

César Damián’s Memoria y Migración (Memory and Migration) project

Celia Álvarez-Muñoz recommends artist Teresa Margoles

Delilah Montoya recommends artists: Alex Rivera and Margarita Cabrera

Maria de Los Angeles recommends artists: Felipe Baeza, Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio and Joiri Minaya

Jesús Macarena-Ávila recommends artists: Jose Guerrero, Diane Kahlo and Fabio Rodriguez

Author

Macarena-Ávila, a visual artist working in Chicago, Illinois as a “community engager” under the moniker, Instituto de Nuestra Cultura (INC.) since 2008. In Australia, he has given talks/presented exhibits at the Centre for Cross-Cultural Research at the Australian National University, Footscray Community Arts Centre, Victoria College for the Arts, Victoria University with both a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA from Norwich University.