- Eucalyptus and indigo dyed yarn warp threaded onto the loom ready for weaving. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Polyanthemos eucalyptus – also known as red box. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Weaving and indigo teachers. Image credit: Siri Hayes

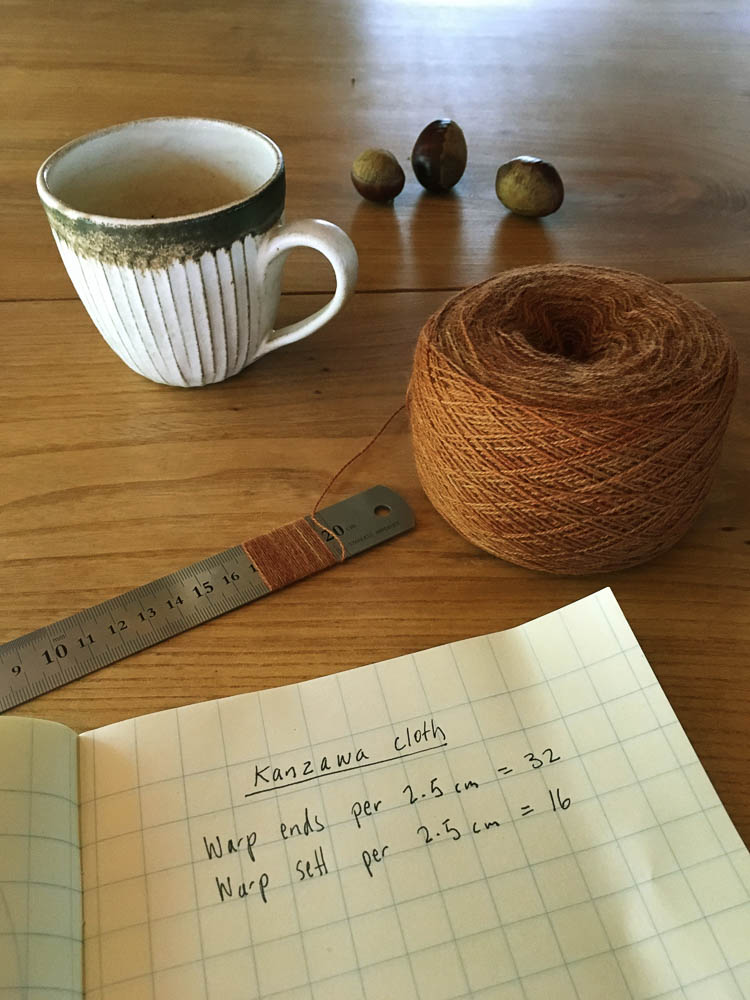

- Warp plan for the Kanazawa cloth weaving. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Calculating how many threads per inch for the warp. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Japanese swift used for winding skeins of yarn into balls. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Paul, Oli and Luella in a weaving workshop. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Kanazawa cloth on the loom. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- At one point a warp thread broke and weaving teacher carefully mended it. Image credit: Siri Hayes

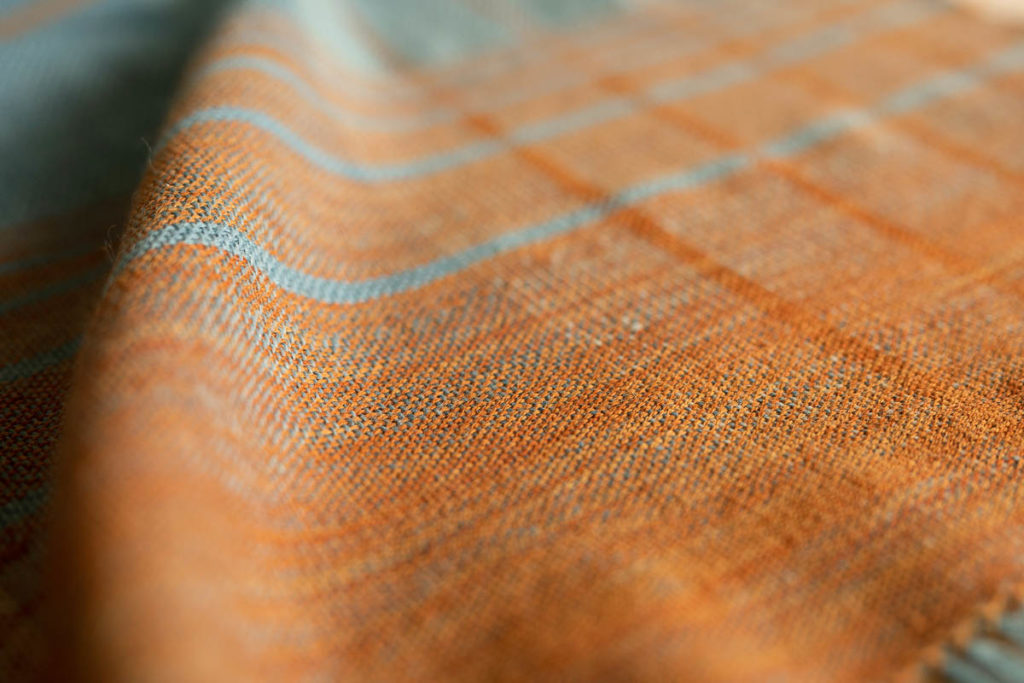

- Detail of the finished Kanazawa cloth weaving created with indigo and eucalyptus dyed yarn. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Detail of the finished Kanazawa cloth weaving created with indigo and eucalyptus dyed yarn. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Detail of the finished Kanazawa cloth weaving created with indigo and eucalyptus dyed yarn. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Siri and weaving teacher. Image credit: Luella Wood

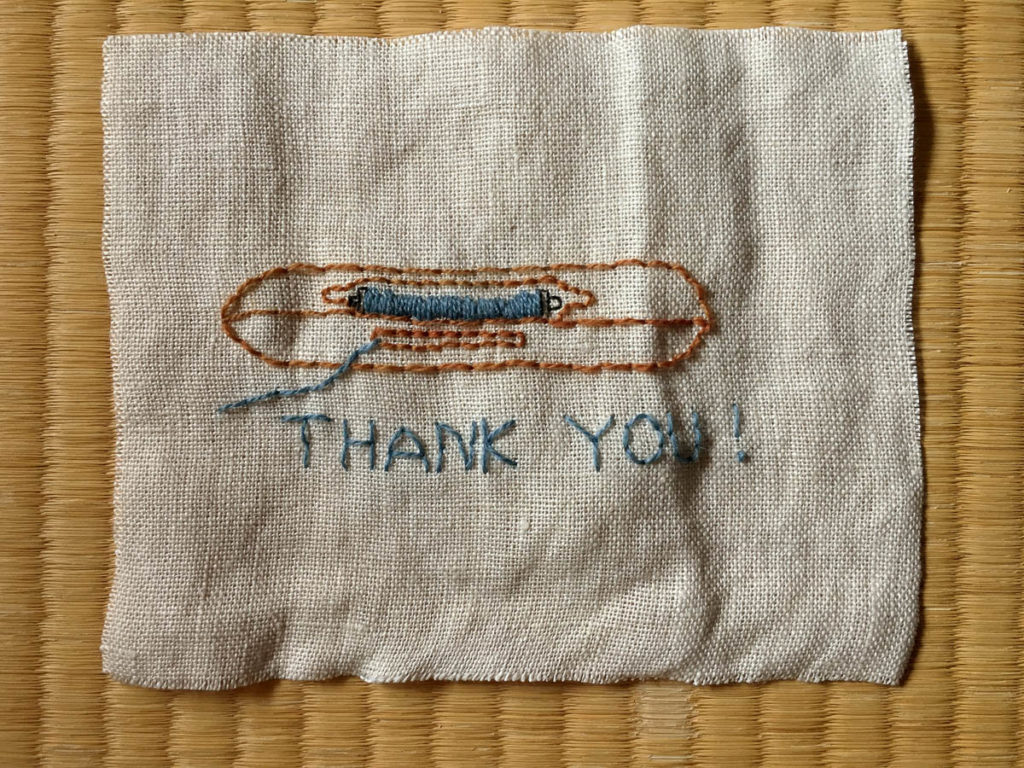

- A little embroidery made from leftover eucalyptus and indigo dyed yarn. Siri made one for each of the indigo and weaving studio staff. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Matcha and gold leaf for Luella type C photograph with the Kanazawa cloth used as a backdrop, 2018. Image credit: Siri Hayes

- Vanilla and gold leaf for Oli type C photograph with the Kanazawa cloth used as a backdrop, 2018. Image credit: Siri Hayes

Photographer Siri Hayes travelled to Kanazawa to combine Australia eucalypt-dyed threads with those in Japanese indigo. We were most curious to learn why a photographer decides to go to Japan and weave.

Welcome message

✿ What prompted you to make this trip to Japan?

In September and October this year, I travelled to the Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts And Culture in Japan to make some new artwork. I have travelled to Japan a couple of times with my husband Paul, who is a ceramic artist, before we had children. With our love of Studio Ghibli movies and Japanese food, they were as keen as us to go.

Over the last couple of years, I have also been involved in a casual craft group which is comprised mainly of Japanese women. At these crafternoons we have explored different craft areas such using kintsugi decorative gold techniques to repair ceramics, pulling apart old futons to make new zabuton floor cushions as well as using eucalyptus leaves for botanical dye.

Earlier this year I received a visual art award that required a research outcome. This gave me the opportunity and prompted me to pursue a few areas of interest in my art practice which I hadn’t prior to the award.

In my practice, I mainly work with photography. Over the past eight or nine years, I have also brought domestic crafts into my artwork as a method to investigate notions of place, family, intimacy and also to reiterate philosophical ideas around the photographic medium itself. I have been particularly interested in using botanical dye to record place in a similar indexical way that photographs contain the trace of light from the place it was recorded. Botanical dyes retain the trace of colour from the place. Both botanical dyes and photographs exist by being connected to the place they are extracted from. They are actual evidence of the place and retain traces of it.

During my time of experimenting with botanical dye, I have been particularly attracted to obtaining the indigo hue. There is a similar alchemical process to analogue black and white darkroom photography in which one can see things magically appear before their eyes. I never cease to be in wonder when watching an image appear in the developing tray in a darkroom. In much the same way, I find it magical to watch yellowy-green fibre turn to cosmic blue within seconds of coming into contact with oxygen when gently removed from an indigo vat. Indigotin is a dark blue compound that is the principal dye in indigo. It only becomes soluble and available as a dye when it is dissolved in a liquid in which the air has been removed. The traditional method for this is fermentation.

Indigotin is present in many different plants worldwide and I have been particularly keen on working with an Australian plant species called Indigofera Australis. As far as I know, Indigofera Australis has been used for pink dye by Aboriginal Australians using the usual simmering process for other botanical dyes, but not for achieving blue through fermentation. Japan has a strong tradition of using fermentation vats to produce indigo blue products. It has become a rare craft to master: though many still use the natural indigo powder, they include a toxic chemical to “reduce” their vats for dyeing.

I was very excited to come across the Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture for a few reasons. Firstly, because they have proper natural fermentation indigo vats that are completely natural and non-toxic. Secondly, the Centre is run by the Kanazawa City Council and they openly encourage the participation of children in the studios. This second point is important to me because my family are very much at the heart of my practice. I have been interested for many years in the idea my family as my “studio” in which I investigate notions of intimacy and photography through documenting the creations my children and husband make as well as the various intercultural ways we are woven together.

✿ Can you describe the weaving project?

Before leaving our home in Melbourne, Australia for Kanazawa, Japan I gathered leaves from a local council roadside polyanthemos eucalypt (also known as Red Box) tree pruning. Where we live in Eltham, there are many Red Box eucalypts that are endemic to the area and when simmered for many days produce a beautiful rusty orange-red dye. I dyed some finely spun wool with the intention of taking it to Kanazawa to weave with similar wool that I brought with me which I planned to dye in the indigo vats upon arrival at the Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture.

My intention was to make a weaving that wove together colour from the place my family and I come from with wool coloured by the place we were visiting to create an object that was literally about meeting and crossover. And that is what I did. Upon arrival at the Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture I promptly used the natural ferment indigo vats to colour wool in lighter and darker blue hues to use in the weaving project.

I also intended for the weaving to be used as a backdrop for individual portrait photographs. Initially, I thought it might be good to create photographic portraits of the people I met at the craft centre in Kanazawa along with portraits of my family. However, the project took a slightly different turn when I had an interesting idea to crossover some other elements into the photographs. I decided to make portraits of my children holding ice cream cones decorated with gold leaf. Kanazawa is the centre in Japan for gold leaf lacquer wares and a unique tourist attraction is the possibility of purchasing and eating a gold leaf ice cream. How could one resist such an experience particularly when next to the incredible Kenrokuen Gardens?

In the past, I have explored the idea of food in photographs with my children as a bribe and still life. This seemed a relevant extension of this theme. I asked the kids if they would be happy to sit for a portrait photograph holding a gold leaf ice cream with the promise of consuming it post the photograph. I am interested in how photography and parenting have similarly complex issues around power and control.

I hope the portrait photographs with their woven backdrop represent a blending of place, person, craft and experience.

✿ What kinds of facilities and people did you work with in Kanazawa?

The Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture has natural indigo fermentation vat, botanical dye, weaving, screen printing and woodblock printing studios as well as a gallery, education space and accommodation. Visitors are able to enrol in one hour to half day and full day directed workshops or hire the studios for personal projects. We did a combination of all the above. The directed workshops were ideal for learning how to use the indigo vats correctly and specifically for how they are operated in the Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture. I have done some master classes with Malian master indigo dyer Aboubarker Fofana and done some of my own experiments using fermentation and natural techniques, but there is so much to learn. The directed workshops were also great for introducing Paul and the kids to the possibilities of indigo dyeing. They also enrolled in weaving and screen printing workshops and produced some wonderful and impressive work which appears on tee shirts in some of the portraits I created.

The Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture has a central office and reception where we paid for our accommodation, studio access and workshops. They were wonderfully kind and polite staff who often gave the children little gifts. The director Mr Tadashi Ohura was particularly generous and welcoming. The central office liaised with each of the studios and we often had extended interactions as we stumbled through language barriers with lots of gesturing, concentration, polite laughter and Google Translate.

Each studio had staff who were responsible for its smooth running. For example, in the indigo studio, there were 2-3 part-time staff who rotated their roster so there was always someone there. We mainly worked with Ms Yamazaki Nahoko who is a young woman studying textile design at an art and design college in Kanazawa. Her knowledge and care for the indigo vats was deep. When she wasn’t running workshops she was keeping the indigo vats happy, fed and warm. This involves churning the vat and checking its health by smell, feel and sometimes taste. Testing for the right pH level and adjusting using wood ash lye with bran or sake means the bacteria are happy and keep the indigotin in its soluble form. She would weigh our fibre to make sure we would not overwork and exhaust the vats on any given day. These vats are living organisms and possibly comparable to beehives. Outside the indigo studio, they grow persicaria tinctorial or Japanese indigo. It is a small patch for show and education. The Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture sources its indigo from the Tokushima prefecture further south where indigo flourishes in the warmer climate.

Upstairs from the botanical dye studio is the weaving studio where I worked with three kind and patient weaving staff as well as half a room full of local weavers who hire looms for their personal projects. I have done freeform weaving since I was a child, however I have only recently begun weaving on traditional looms with between four and eight shafts and the many staged warping process. I encountered familiar and different tools. For example, I have used Western style swifts which are used to wind skeins of yarn into balls but I absolutely loved the vertical Japanese-style swift that reminds me of a Ferris wheel and which I found much easier to use. There was a threading tool I also really liked using. As my Australian weaving teacher Amanda Ho predicted before I left, all the looms were in beautiful working condition.

✿ How was the experience different from what you anticipated?

I didn’t really know what to expect upon arrival at the Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture. There is one English pdf on their website and, as a non-Japanese speaking person, the English translation of the page on Google Chrome was still a bit tricky to interpret. However, I always find that it doesn’t really matter how much description one has of a place before arriving at it for the first time, it is always different to what one expects.

I wasn’t anticipating the centre being situated on such a steep large piece of lush and wild land. Sitting on a perch overhanging the long, steep and winding driveway up to the centre were two small handmade totoros. They added to the magical wildness of the place along with buzzing cicadas and crickets.

When we arrived at the centre we were greeted by the kind Mr Yamazaki Akio. He showed us up to the beautifully clean and generous tatami mat room we were staying in with an exquisitely shibori-dyed noren (half door height curtain hanging from the door frame) at its entrance. Our room was called ‘Ai’ (the Japanese word for indigo). We were the only people staying in the accommodation at which there were three similar large size rooms (all named after different botanical dyes used at the centre) and one smaller single western bedroom the whole time we were there.

I had no idea Nahoko, the indigo teacher, would be so young and relaxed but also knowledgeable and happy to wait for us to understand why, for example, we could only dye a smaller amount of fabric than perhaps we had initially wanted to. She was patient and also trusting enough, once we did understand, to leave us on our own to work.

Upstairs in the weaving room, I absolutely loved working with the staff. One woman has a great sense of humour and I loved that she teased me into laughing over my anxiety about my project. Another staff member, when I was really struggling with my technique, simply sat down and showed me the most gentle gesture of working with the loom that I will never forget and be able to properly express in words. I can definitely confirm that the lightness of the cloth I ended up creating was something completely unexpected and most certainly attributable to her demonstration.

Finally, I generally begin creating any artwork with a kind of “vision” of what it might end up being or looking like, but always excited and tense round knowing that it probably won’t be anything like it. I find keeping a creative project on track requires a gentle overarching guiding hand that is equally alert to a sort of all-senses-open-to-contingent-incidents-happening balance. Having the overall vision with an openness to the contingent is the fine balancing act for me in creating artwork that has some zing.

This kind of concentration is quite exhausting and making artwork in a completely new place can be quite challenging for these reasons. However, there is a calmness at the Kanazawa Yuwaku Sousaku no Mori Centre for Crafts and Culture that I think meant it was possible to have the important contemplative creative space to be able to achieve what I set-out to do with all the contingent happenings only adding layers of interest to the final outcomes.

Author

Siri Hayes is a Melbourne based Australian visual artist who predominately works with photography, video and domestic crafts to explore notions of place, family and intimacy. She regularly exhibits work in exhibitions at venues such as the National Portrait Gallery, National Gallery of Victoria and Heide Museum of Modern Art amongst many other gallery spaces. She is currently working on a project exploring her family history during the 1970’s around environmental politics at Westernport Bay near Melbourne for an exhibition at the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery that will form part of the 2019 Climarte Festival

Siri Hayes is a Melbourne based Australian visual artist who predominately works with photography, video and domestic crafts to explore notions of place, family and intimacy. She regularly exhibits work in exhibitions at venues such as the National Portrait Gallery, National Gallery of Victoria and Heide Museum of Modern Art amongst many other gallery spaces. She is currently working on a project exploring her family history during the 1970’s around environmental politics at Westernport Bay near Melbourne for an exhibition at the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery that will form part of the 2019 Climarte Festival