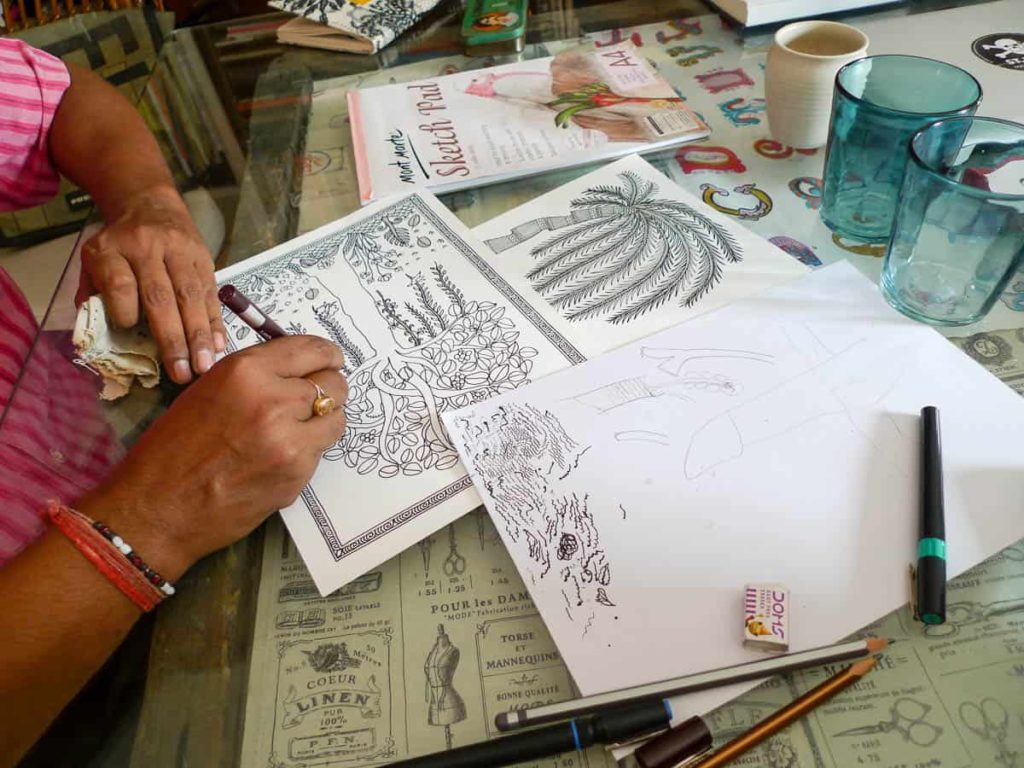

- Mandy & Pushpa reviewing drawings early in the process.

- Pradyumna, Pushpa, Minhazz and Ishan discuss an image.

- Ishan showing an antique German carpet beater collected in Australia that resembled an item from Mandy’s photo archive

- Pushpa, Pradyumna and Ishan absorbed in their drawings

- Godh: in the lap of nature 3 panels, 2016, Eco-ink, coated cotton. 188x107cm each panel, an installation image of the panels in OED Gallery, photo: Kochi Atul Dube, Moonlight Pictures

- Detail, Godh: in the lap of nature 3 panels, 2016, Eco-ink, coated cotton. 188x107cm each panel, an installation image of the panels in OED Gallery, photo: Kochi Atul Dube, Moonlight Pictures

- Pushpa creating individual drawings early in the collaboration

- Installation image at OED Gallery, with Indian artists Simrin Mehra-Agarwal and Vibha Galholtra enjoying the work.

In late 2016 I travelled to Delhi India to undertake an Asialink residency with the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative. It was a rare opportunity to research the work and achievements of an extraordinary organisation that will inform my own work over coming years. Delhi itself provided me with endless opportunities to enjoy rich cultural experiences on a daily basis. I found myself in all sorts of shared spaces; engaging with others in homes, businesses, workshops, yoga classes, art talks, performances, beauty parlours, cars, auto-rickshaws, galleries, at heritage sites and on the street. These engagements were often uplifting, sometimes confronting and always interesting, however, for an artist perhaps the most satisfying way to share space is in the creation of work.

An invitation to exhibit in Kochi at the time of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (in Common Ground: The Serendipitous Happenstance Project, curated by Helen Rayment) presented a chance to focus on a long-held interest in drawing and build on existing networks to initiate a new collaboration with three Delhi-based creative artists. It also proved to be a fertile laboratory for exploring a central aspect of my work, the possibilities art allows for meaningful connection or relationship between individuals of different cultural identity.

Earlier that year at QAGOMA I had enjoyed seeing artworks by Pushpa Kumari and Pradyumna Kumar in the Asia Pacific Triennial 8 presented in Kalpa Vriksha: Contemporary Indigenous and Vernacular Art of India co-curated by Minhazz Majumdar. Among a range of works from a number of traditions, Warli, Gond, Mithila, Kaligat paintings and Rajwar sculpture it was their detailed line work, intricate pattern and bold compositions of the works that caught my eye. Little did I imagine that in less than six months I would meet the artists, no less be working with them. In some respects, this is the magic of India, and it must be said, social media, that may both inform and allow for an ease of conversation and connection. Shortly after arriving in Delhi, I found myself enjoying warm hospitality at the home studio of Minhazz, being introduced to Pushpa and Pradyumna and starting a collaborative dialogue. Minhazz has continued to be a staunch supporter of the project, which she hoped would present new opportunities for the artists to extend their practice.

I was aware of Ishan Khosla through his work with Sangam: the Australia India Design Platform, a project that evolved from conversations between designers and craftspeople in Australia and India and had hoped to meet him during the time I would be in Delhi. Fortuitously, the opportunity came very early in my stay as he was presenting a talk, “Work in Progress for a better tomorrow” at the Gujral Foundation that outlined his approach to working as a contemporary designer within the complexity and richness of an Indian context. From our first official meeting at a café we developed an easy rapport. Most of the commissioned artworks I have undertaken required I work closely with a designer, so it seemed entirely natural to invite Delhi-based Ishan to join the collaboration.

In preparing this text, I went back to voice memos recorded on my phone at an early visit to Minhazz’s studio and then at the first meeting of the working group at Ishan’s studio. Sitting on my deck in autumnal Brisbane, I was transported back eight months to Delhi locations hearing voices both Hindi and English, overlaid by sounds from the distant street. Listening again, I was struck how the warmth, gentle humour and richness of our conversations were suffused by goodwill. These early conversations set a loose framework for how to proceed, not as a process of merely commissioning traditional artists to interpret an idea, but as a truly collaborative undertaking. It was to start with line, observe the personality of each person’s mark making and consider the ways to synthesise our very different approaches. Our drawing project took a cue from the title of the larger exhibition and sought to create a shared space developed from the shared memories of the landscapes of our childhoods.

We commenced weekly drawing workshops, initially depicting flora and fauna. My experience of being in and surrounded by the natural world was significant and shared by the others. There were conversations in both Hindi and English as the group spoke of the diverse terrains of Bihar and Kochi in India and rural Gippsland in Australia recalling plant forms, domestic pets, other animals and open spaces. A full day stretched over lunch when we were joined by the designers and staff from Ishan’s studio. There were endless cups of tea provided by the ever-smiling Suresh, much goodwill and laughter with discussion around the differing techniques and styles that each individual’s training have fostered.

Pushpa was a student of her grandmother, renowned Madhubani painter Maha Sundari Devi, one of a group of artists who responded to a government initiative in the 1960’s to work on paper. As Minhazz explained, “Until that time the paintings, typical of the Madhubani region of Bihar, North India, had been created as ceremonial paintings on walls and floors, depicting religious and social themes. These paintings were means of visual education, a way of passing down stories, myths and social values from one generation to another.” Pushpa’s brother-in-law Pradyumna came to art later in life after completing an MA in Geography and a career as a land surveyor, his years of experience in the field providing a wealth of knowledge of trees and natural forms.

What was astounding to me was the way Pushpa and Pradyumna would work. Their training has required faithfulness to the techniques of their ancestors thus ensuring a mastery of technique, rather than valuing inventiveness. As mature artists, each has pushed the boundaries of the art form to incorporate ideas and treatments that reflect their individual interests and concerns. This mastery meant that after some brief discussion about the day’s work, they could rule up a border around a page and launch into the creation of meticulous imagery drawn from an intuitive inner archive. This was completely contrary to my 1980’s art school training that required drawing to be at best from life or at least from adequate photographic reference.

Another point of difference was my reticence to make marks on the work of another artist; it seemed a somewhat transgressive act. However, this most intimate of actions was the entry point for solving the quandary of our very different drawing styles. After many years of working together, Pushpa and Pradyumna were quite comfortable with the notion of commenting or even contributing to the creation of work. Thus the synthesising of our work progressed such that eventually a drawing was crafted with multiple artists working on the one image, to our great mutual delight!

A resolved artwork was developed from the collective archive of drawings for an exhibition at OED Gallery in Kochi, opening 10 December 2016. Ishan transformed the results of several months of weekly drawing workshops and discussions into files for large format prints on cotton using eco-solvent ink. The selection of a coated cotton material for the image support has a paper-like quality that reflects the original genesis of the project’s drawn imagery.

The panels created something of a dream landscape of our collective memories, oversized plant forms seeming to dwarf figures of children and animals. There was a great response to the work with viewers being both charmed with the subject matter, concept and freshness of the work, capturing a sense of being a truly collaborative undertaking.

The panels were hung in a more restrained presentation to work as part of a group exhibition in this idiosyncratic space. It will be good to have an opportunity to explore presenting the work as a solo installation in subsequent venues. We are currently developing a further extension of the suite in collaboration with a master screen printer in Delhi and are experimenting with embroidery that extends the interpretation of the original drawings.

The project is deceptively simple and teases out many ideas around ways of art making from divergent cultural traditions. I have been astounded at the ease with which we developed a shared understanding of our process and look forward to extending the work into a new domain. It was an unexpected but truly amazing opportunity for which I am extremely grateful.

Further reading

Bernal.A. 2015 “Kalpa Vriksha: Contemporary Indigenous and Vernacular Art of India” TAASA Review Vol 24 No 3 September. Page 7

Author

Melbourne-born Mandy Ridley now lives and works in Brisbane. Her work includes exhibitions and permanently installed public commissions that draw from material culture research, using colour, pattern and craft to explore points of resonance between people of differing cultural experience. In 2016 she undertook an Asialink Residency with the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative in Delhi, supported by Arts Queensland. This year Mandy is back in her studio creating work in response to her research and experiences. She is eager to pursue the opportunities that have arisen for ongoing collaborations in India. Website: mandyridley.com

Melbourne-born Mandy Ridley now lives and works in Brisbane. Her work includes exhibitions and permanently installed public commissions that draw from material culture research, using colour, pattern and craft to explore points of resonance between people of differing cultural experience. In 2016 she undertook an Asialink Residency with the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative in Delhi, supported by Arts Queensland. This year Mandy is back in her studio creating work in response to her research and experiences. She is eager to pursue the opportunities that have arisen for ongoing collaborations in India. Website: mandyridley.com