“Only through associations of many people assisting each other, where each provides another with some share of that which is necessary for survival may a person attain that level of perfection to which he is destined by his nature.”

Central Asian philosopher Al-Farabi in the tenth century

It’s a warm summer night and the town square of Tashkent is glittering with neon light decorations. Families and friends stroll around to enjoy the many diversions. A Turkish ice-cream seller is entertaining customers by dexterously pretending to drop their cone just before handing it over. Meanwhile, the main stage is hosting a free concert with local Uzbek pop stars. But something is different here. Projected behind the singer is a video of ikat weaving. Indeed, the whole concert is accompanied by a video backdrop of craft processes. Someone has obviously been thinking about how the young generation could take a greater interest in crafts.

One positive benefit of the nationalism that is spreading throughout the globe is increased value given to local crafts. This is particularly evident in Uzbekistan, which has an ambitious policy to promote its crafts both at home and internationally. Along with funding for 60 craft centres, artisans are deemed exempt from taxes.

You can see this already in the biennial Handcrafters Festival of Kokand, which is a personal project of the President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and involves all 33 government ministries (even the Minister of Transport ensures that the roads are smooth for foreign guests). Kokand lies in the fertile Ferghana Valley, which is a treasury of Intangible Cultural Heritage, including the lapar and yallah tongue-twisting songs recognised by UNESCO. Its magnificent nineteenth-century palace is a legacy of the Khanate, which brought specialist artisans from across the region.

- Performance to welcome guests at Kokand craft festival

- Kokand’s ritual offering of bread and halva to guests.

- Kokand music, dance and ikat

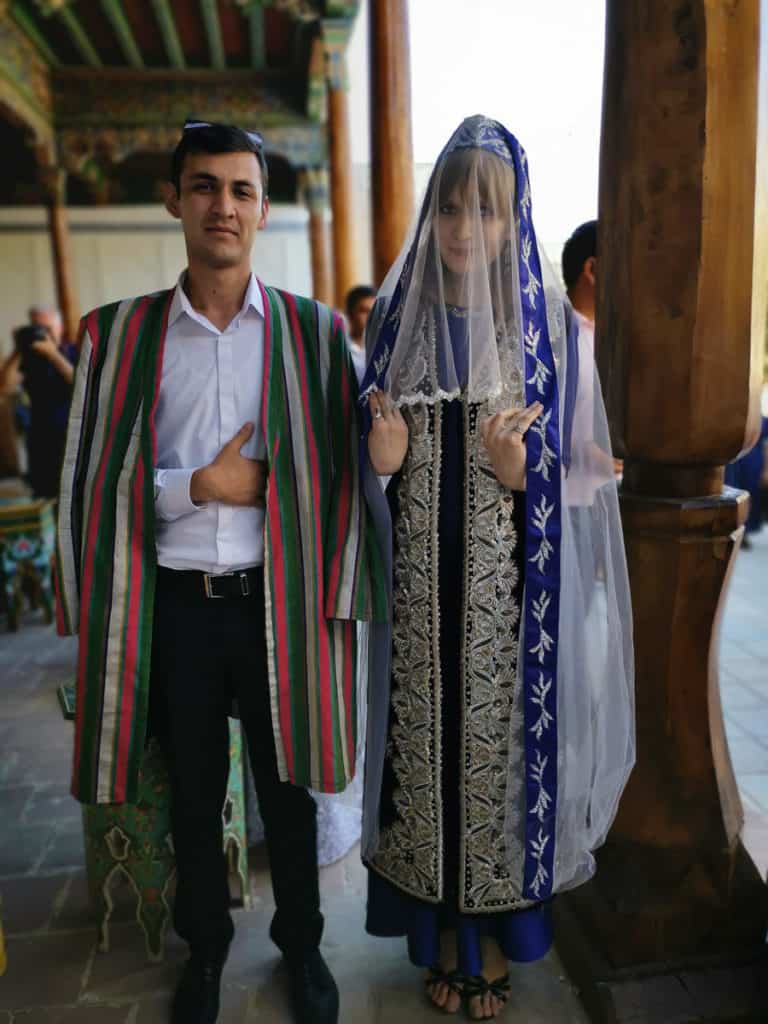

- A couple dressed as traditional bride and groom.

Kokand is particularly known for its wood crafts. The intricate leaf-like design reflects the islimi principle of an unending pattern reflecting natural abundance. Woodshops thunder to the sound of chekish stamps making tiny dots on the background of the design, giving the surface a fine texture (similar patterns can be found on the local bread). Notable objects include the mashab stand for reading books and the magnificent muqarnas pillars that represent the stars and sky in monuments and mosques.

- The texture produced by chekish stamps on wood designs

- Bread from Fergana vallery

Woodcrafts traditionally are taught in the workshops to apprentices, who labour until they are ready to have their own workshop, at which point the master usually provides him with his own set of tools. Now in Kokand, wood crafts are being taught in a college, which enables greater consideration of design. We also see it possible for females to take on the craft.

Certainly, Uzbekistan has many fine crafts we can enjoy, such as the magnificent suzani embroideries, silk ikat from Margilan and green and blue ceramics. But what do these actually mean to Uzbek people? At a soiree in a wood workshop, I sought the advice of a craft scholar in Kokand. I was particularly curious about the name of the national craft organisation, Hunarmand. What does the word “hunar” actually mean?

- Manzurakhon Mansurova, director of six museums in Kokand, in front of the mural where she had posed on the horse.

- Abdulativ Turjaleef, director of the Museum of Great Scholars and a mushab for reading books.

- Elnura Sadykova, principal of the college of handicrafts

He told me that hunar is more of a skill than an object. The scholar Yakhyo Dadaboyev registered 708 of these hunar. Some include conventional craft skills, such as glazing or weaving, but there are others that relate to consumable products. These include making kinds of halva (a specialty of great pride in Kokand). And there are ten related to horsemanship which was included in deference to the President, a keen equestrian.

Abdulativ Turjaleef, head of Kokand’s Museum of Great Scholars added that it was beholden for every poet to know as least one material craft. Mohammad Ali Khan knew thirty crafts and was a renowned calligrapher. The museum itself focuses on the revival of papercrafts, such as the ancient cotton paper notable for the crisp sound of its paper.

Importantly, hunar are not unique to artisans. It is said that “40 hunar are not enough.” Hunar are a sign of your capacity as a person.

It should be noted that this 40 has special significance in Central Asia. The chilla in Islam is the forty-day period of intense spiritual reflection spent in isolation by religious leaders. It also refers to the 40 hottest and coldest days of the year. For an individual, the forties represent the decade when he or she will achieve things of significance.

There are many legends in Central Asia related to 40. The word “kyrgyz” in Kyrgyzstan means 40, representing the number of tribes who came together to make the nation. A recently revived epic, tells the story of 40 women warriors who gathered together in sixth century BC to defend the rights of Gulaim, a fifteen-year-old girl who had rejected marriage. The Uzbek film 40 Days of Silence (Chilla) tells of four generations of women who live in the absence of men. And when a baby reaches 40 days, the family gather for the beshik toi celebration, when a special cradle is gifted.

The other element intrinsic to craft is the collectivity known as a mahalla. Along with all other Uzbeks, craftspersons belong to a neighbourhood association. There are more than 10,000 mahallas in the nation. At the beginning of the day, Uzbeks gather in their mahalla around the choikhana, a communal tea room, to chat and share issues. The mahalla offers a communal space where children from different families can play together safely.

The government currently has a program to use the mahalla as a unit through which to channel support for crafts. Uzbekistan’s One Mahalla One Product program reflects similar policies in other countries that are seeking to stimulate local communities, such as One Commune One Product in Vietnam.

There’s much to reflect on here. Our modern studio model of craft draws from the romantic Western concept of the inspired genius like Van Gogh alone in his studio. This is very effective in specialisation and development of unique artworks. But what Uzbekistan reveals is that craft can also flourish as a communal activity. Craft is not a specialist domain, but a set of skills that every Uzbek contributes to the common good.

What are your 40 hunar?

Comments

Hello Mr Kevin Murray

I am going to thank you for this valuable well-written article about our country Uzbekistan. Four days of being your driver, I and people around you have learned a lot about humanity, character and about Australian culture. I wish you the best of all, May God pour love and care on you, your family and close people.