- Vipoo Srivilasa, The Masks of Me, 2018, mixed media installation, dimensions variable, photo: Shane Hulbert

- Vipoo Srivilasa, Thai Language, 2018, mixed media installation, dimensions variable, photo: Shane Hulbert

- Tammy Wong Hulbert, Transient Home City, 2016-18, mixed media installation, dimensions variable

- Hoang Tran Nguyen with David Nguyen, Making Crackers, 2011, HD video 3.33 min, Finale, 2011, HD video 2:22 min , photo: Shane Hulbert

- Rushdi Anwar, Irhal (Expel), Hope and the Sorrow of Displacement, 2013 – ongoing, burnt wooden chairs, black pigment and charcoal, dimensions variable, photo: Shane Hulbert

- Rhett D’Costa, Becoming Differently, 2018, mixed media installation, dimensions variable. Individual works: Holding Hands, 2018, photograph, 100 x 140cm, An Indian spice table/dodder vine/mistletoe/haustorium/the dead hair of a cultural geographer/unidentified bird nests/a collapsing form, 2018, mixed media, dimensions variable, photo: Shane Hulbert

- Nikki Lam, Falling Leaf Returns to Its Roots, 2014 HD video, photo: Shane Hulbert

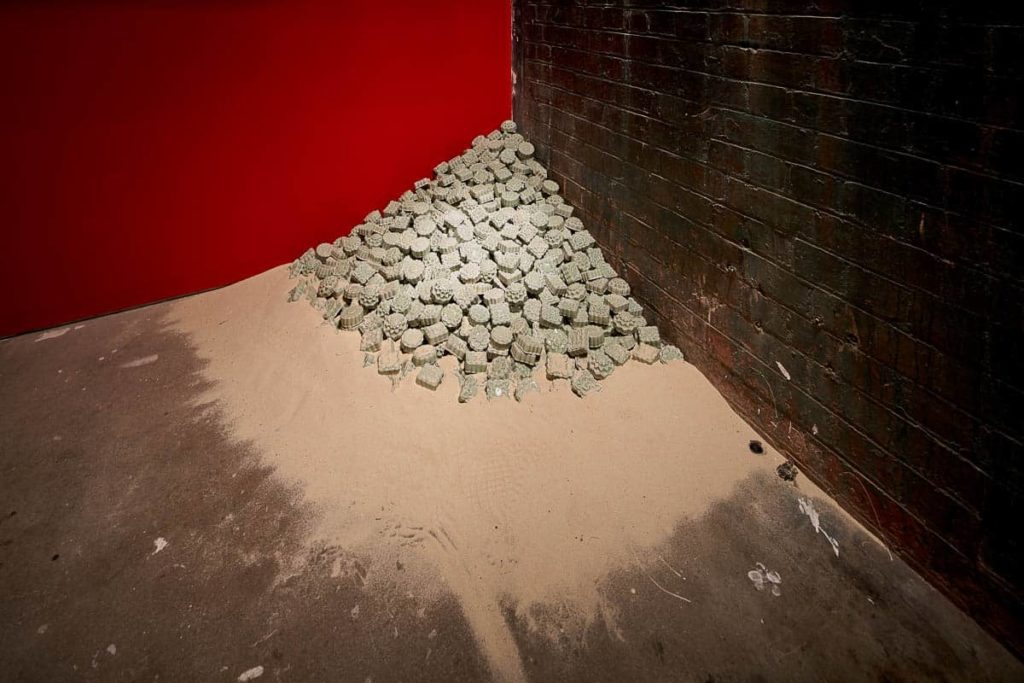

- Phuong Ngo, Slippage, Mooncake, 2018 – ongoing, Celadon glazed porcelain and sand, dimensions variable, photo: Shane Hulbert

- Eugenia Lim, Artificial Islands (Interior Archipelago II), 2018, collaborative performance installation, sand, plastic, dimensions variable, photo: Shane Hulbert

- Sofi Basseghi and Ehsan Khoshnami, Elusive Paradise, 2018, video, mixed media installation, dimensions variable, performance: Michka Mansour, sound design: Ai Yamamoto, photo: Shane Hulbert

HYPHENATED began as a conversation between two artists of different Asian heritages, Phuong Ngo and myself. Our experiences had intersected but were also completely different; we had both experienced living between cultural spaces as Australians of Asian backgrounds. The conversation grew, expanding to ten artists of similar backgrounds based in Victoria. We identified that each of the artists were having separate conversations with their own heritages, but together we were able to present an empowered voice as a community of diasporic Asian-Australian artists, able to critique and express our varying positions in Australian society—the hyphenated space between Asian-Australian culture.

In Australia, Asian culture is often defined by our closest neighbours in South East Asia, where we have strengthened migration and economic ties. However, the continent is much broader, constituting more than half the world’s population, where thousands of cultures, art forms, languages and religions originate demonstrating astounding diversity. The Asian experience is diverse, encompassing the spectacular growth and economic wealth seen in modernised and urbanising economies, through to war, revolution and ongoing conflict and unrest, particularly in central Asia and the Middle East.

Mass migration to Australia has resulted in cities that are vibrant with transnational communities identifying with many other cultures. Yet due to our colonial past, Australians have identified more closely with European culture, even though our geographic location is in the Asia Pacific. This is an on-going and contested area of cultural debate in Australia since the rise of postcolonial literature in the 1990s, and has lead to the formation of several events and institutions, including the Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane and Gallery 4A (The Asian-Australian Artists Association) in Sydney, who form a legitimate and powerful part of the Asian and Asian-Australian artistic voice. In Melbourne, with the internationalisation of contemporary art practices and the rise of contemporary Asian art in Asia, there is more exposure to the work of international Asian artists in our institutions, but with limited meaningful connection to the lived experience of being in Australia.

As artists working in Melbourne, we became aware of the need to bridge this gap by presenting the voice of the diaspora from a Victorian outlook, resulting in this exhibition. What emerged were ten artists conversing with diverse ideas ranging from reflections on their personal and cultural histories, the relationship between the individual and collective in society, and loss, transformation and displacement through migration. Working within the Substation’s compartmentalised gallery, artists were assigned to each of the rooms of the former industrial space, allowing the curation of the exhibition to adapt to the site and conditions.

Situated in the hallway, and positioned as the metaphorical spine of the show, was Rushdi Anwar’s Irhal (Expel), Hope and the Sorrow of Displacement. Anwar, who originated from Kurdistan, presented burnt and discarded domestic chairs, acting as a powerful expression of the fragility and uncertainty of conflict, social and political disruption. In setting the scene for the current global crisis of displaced people, and ongoing migration issue affecting Australia, as well as its highly politicised attempts to secure our borders, Anwar’s work links to five other separate rooms. On the left, and the first of the single, small rooms, is the work of Slippage, a collaborative practice by Australian born Chinese Vietnamese artists Hwafern Quach and co-curator Phuong Ngo who presented two interconnected works reflecting on the dynamics of cultural power in Vietnam. Mooncake, a growing pile of celadon glazed ceramic moon cakes (originating from the Chinese mid-autumn festival) was used as a metaphor for China’s historical expansion into Asia, and comment on their current contentious position in the South China Sea. The Cow’s Tongue represents a colloquial term used in Vietnamese to describe South East Asia, with China as the cow’s head. The artists critique the term by suggesting that the tongue denotes China’s continued hunger for political, economic and geographic influence over the region.

In contrast, Iranian born Sofi Basseghi, working collaboratively with architect and artist Ehsan Khoshnami, branches off to a pillared room and presents a series of video works titled Elusive Paradise (2018). The installation creates an immersive environment, following the life of character Michka Mansour, providing insights into how women live between contemporary and traditional Iranian culture, society and religion. The final single room contains Rhett D’Costa’s work Becoming Differently (2018), which focuses on the position of being an Anglo-Indian-Australian. The work draws from post-colonial theory, questioning the place of migrants, when conversations usually take place between the colonizers and the colonized. D’Costa presents images photographed in both Australia and India (2018) and installs these alongside parasitic plants, known for both taking over, and cohabiting with other plants. He asks audiences to consider this slippery space of whether migrants belong in the Australian landscape.

In the first tiered room, the artists have considered their relationship between the individual and constructions of identity. Hong Kong-born Nikki Lam’s ghostly basement video work Still…what is left engages with the transformation of the self through repetitive rituals, gestures and behaviours, which become altered through migration to a new cultural context. Through the lens of migration, and by interrogating the process of becoming, Lam’s second work, Falling Leaf Returns to its Roots (2014), uses the Chinese analogy to describe the circle of life by referencing the iconic Australian photograph The Sunbaker by Max Dupain (1937). In contrast, Eugenia Lim reflects on her Singaporean heritage through her work Artificial Islands (Interior Archipelago II) (2018), where the artist and her participant labourers meticulously constructed a small island in the formation of a Merlion (Singapore’s national icon), to comment on the true cost of competitive nation building. Filipino-Australian Andy Butler’s work Model Minority (2018) interrogates institutional whiteness in the arts by critiquing diversity and inclusion discourse based on racial lines. His works parody the artwork of Jeff Koons and Paul Gauguin, demonstrating that diverse artists still need to assimilate into white artistic cannons to be successful and ironically have the potential to become the latest luxury trend.

In the final room, the works express how diasporic artists continue with their everyday lives and even celebrate their renewed status. Vietnamese artist Hoang Tran Nguyen presents two works made collaboratively with the Footscray Vietnamese community. The two videos Making Crackers (2011) and Finale (2011) demonstrates a passion for karaoke and festive cultural practices and the translation of these practices into the local Melbourne context. The third work, Episode 11, Chapter 5 (2012) focuses on the Japanese American character Harry Ioki, in the 1980s TV series 21 Jump Street played by American Vietnamese refugee Dustin Nguyen. The actor’s refugee status was later incorporated as part of the true identity of the character, thus recognising the status of the Vietnamese refugee in a popular mass media context. My own work Transient Home City (2016-8) developed from my perspective as an intergenerational migrant of Chinese descent. The work evolved from a partnership with the VICSEG Iranian Asylum Seekers Social Health Group in Broadmeadows. Collaboratively we explored and considered renewed ideas of home as transient and mobile, rather than fixed as a result of migration, asking audiences to consider how migration informs the rich cultures and character of our globalizing cities. The final work, hidden downstairs in the subterranean room, is Thai born Vipoo Srivilasa’s Masks of Me (2018). Glow in the dark masks presents the various faces of the artist living between Thai and Australian cultures, navigating and making choices for when it is appropriate to blend in or stand out, celebrating his unique position of being in and between both cultural spaces.

Hyphenated brought together the unique outlooks of each of the diasporic artists, informed by the layered and complicated space in which they live, reflecting the fluid and transforming aspects of a globalising Australian society. Each of the artists has responded to how existing historical and social constructs have shaped and limited our experiences and perceptions of people and places and ultimately what became apparent is the shifting rights of the individual in various social and cultural contexts as a result of these constraints. Presenting an empowered and conscious voice, each of the artists has personally grappled with this position and through the expression of this struggle, their works take ownership of their evolving status.

Hyphenated was an exhibition of contemporary art by Victorian-Asian artists living between cultural spaces co-curated by Phuong Ngo and Tammy Wong Hulbert. It included artists Rushdi Anwar, Sofi Basseghi and Ehsan Khoshnami, Andy Butler, Rhett D’Costa, Tammy Wong Hulbert, Nikki Lam, Eugenia Lim, Slippage, Vipoo Srivilasa and Hoang Tran Nguyen. Literature was curated by Peril, the Asian-Australian Arts and Culture online Journal, responding to works in the exhibition. It was at the Substation, March 22 – April 21, 2018.

Author

Tammy Wong Hulbert is an artist, curator and academic who lives in Melbourne, Victoria. She has exhibited her work and had curatorial experience in Melbourne, Sydney, Shanghai and Beijing focused on cross-cultural dialogue between Australian, Chinese and Asian contemporary artists. She originally trained in Applied Art (ceramics) and Art Administration at UNSWAD, Sydney and completed her PhD at RMIT University on The City as a Curated Space (2012) proposing an alternative model of public based exhibition practices appropriate for globalising cities. Tammy is currently a lecturer in the Masters of Arts Management program, specialising in curating contemporary art and continues to develop projects stemming from her research on the relationship between artists, art practices and the right to the city. (Photo: Shane Hulbert)

Tammy Wong Hulbert is an artist, curator and academic who lives in Melbourne, Victoria. She has exhibited her work and had curatorial experience in Melbourne, Sydney, Shanghai and Beijing focused on cross-cultural dialogue between Australian, Chinese and Asian contemporary artists. She originally trained in Applied Art (ceramics) and Art Administration at UNSWAD, Sydney and completed her PhD at RMIT University on The City as a Curated Space (2012) proposing an alternative model of public based exhibition practices appropriate for globalising cities. Tammy is currently a lecturer in the Masters of Arts Management program, specialising in curating contemporary art and continues to develop projects stemming from her research on the relationship between artists, art practices and the right to the city. (Photo: Shane Hulbert)