- Satoru Itazu printing Portrait – One Eye (2008) by Takanobu Kobayashi at Itazu Litho-Grafik

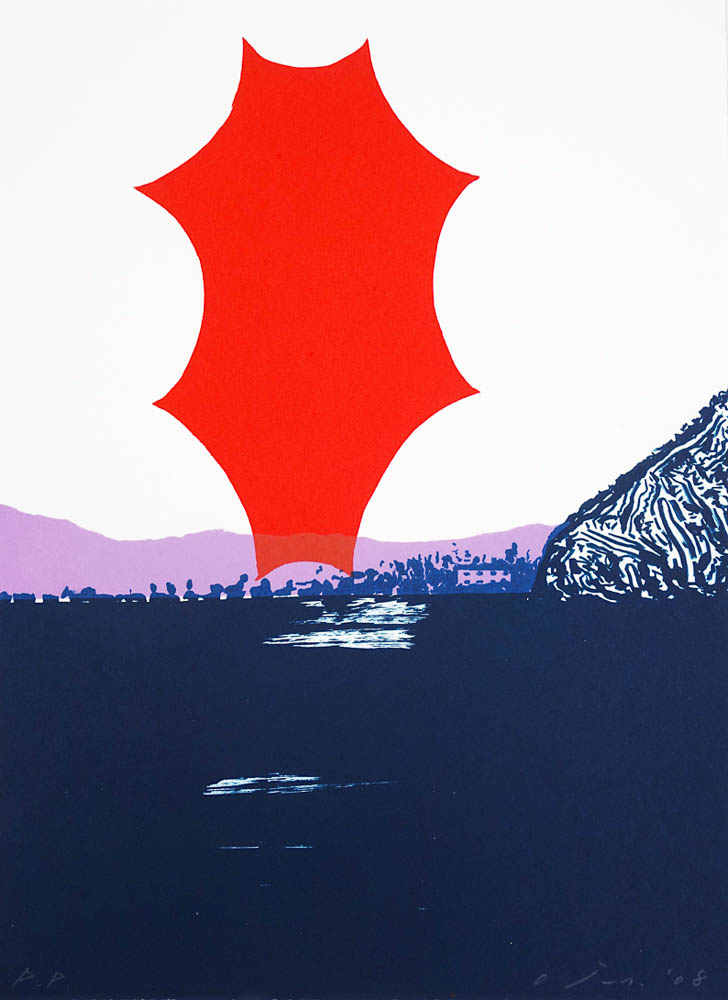

- Seiichiro Miida, Short Story Guruguru Lithograph, 2015 Chinese paper, 68x68cm / Edition of 8 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

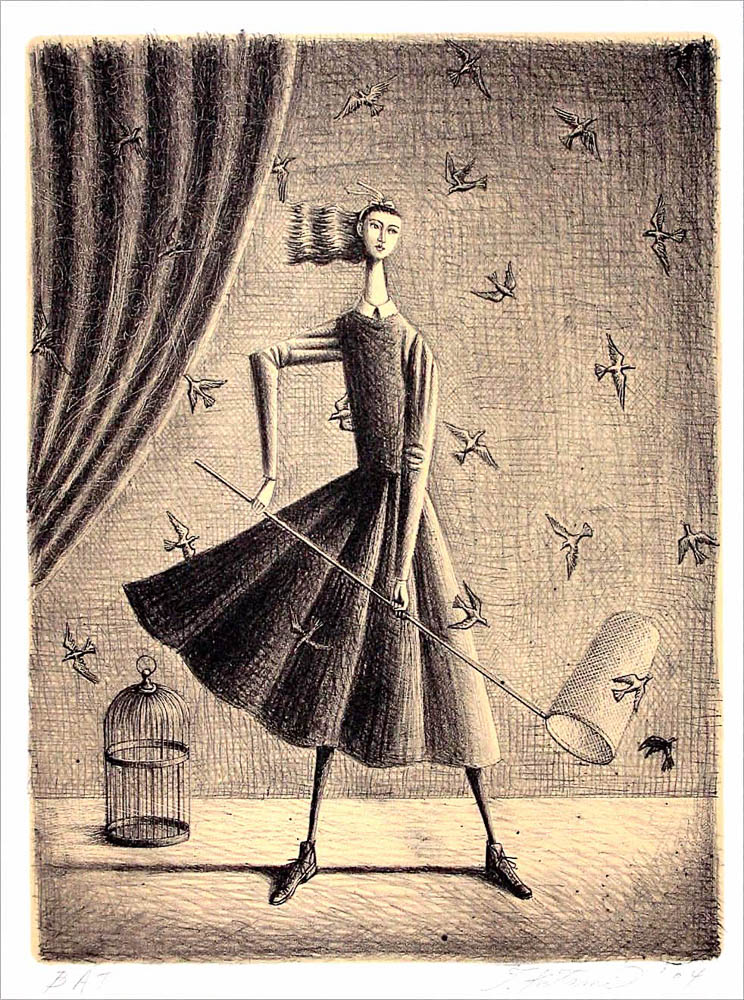

- Takeshi Kitano, Birds Flying Away Lithograph, 2004 Arches paper, 38x28cm / Edition of 32 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

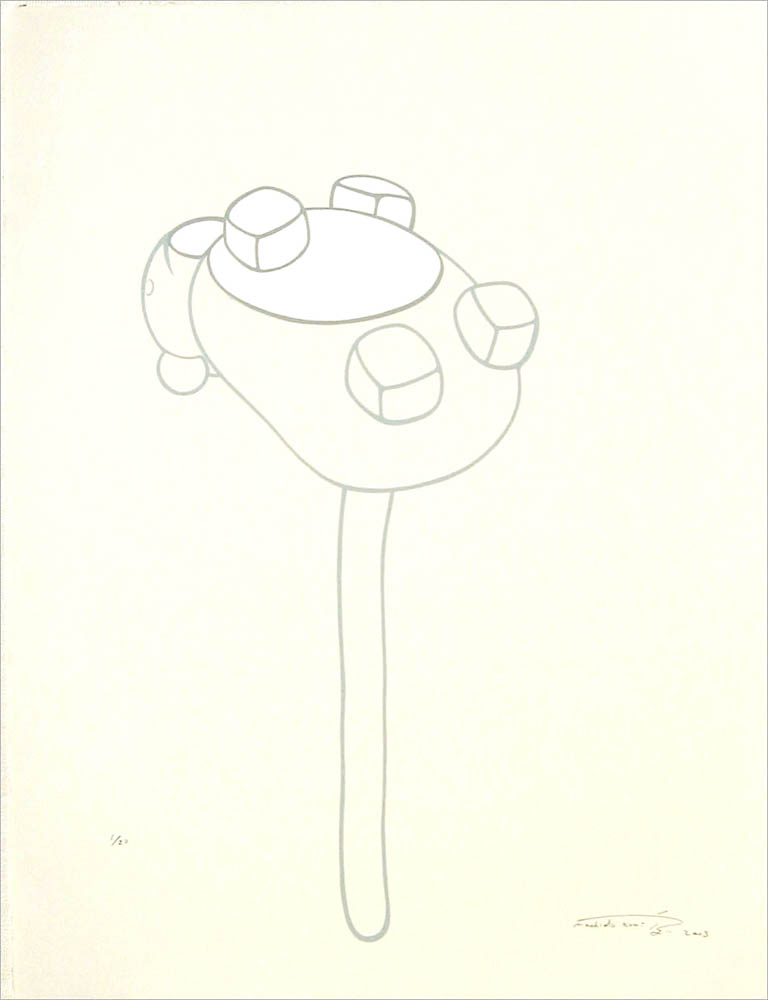

- Yōichi Miyajima, Drain Lithograph, 2002 BFK paper, 90x63cm / Edition of 20 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- Sai Hashizume, Corsage Lithograph, 2005 BFK paper, 380x475mm / Edition of 25 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- Kumi Machida, Depth, 2003 Lithograph, 2003 BFK paper, 65x50cm / Edition of 20 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- Keisuke Yamamoto, Komorebi No.2, 2001 Lithograph, 2001, Izumi paper, 56×76 / Edition of 30 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- Takashi Hayashi, Awai Lithograph, 2011 Mino paper, 50x65cm / Edition of 5 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- Itazu Litho-Grafik – ‘Footprints’ exhibition, 2016 (partial Overview), Museum Haus Kasuya, Kanagawa

- Itazu Litho-Grafk – ‘Footprints’ exhibition, 2016 (partial overview), Museum Haus Kasuya, Kanagawa

- Itazu Litho-Grafik – ‘Footprints’ exhibition, 2016 (partial overview), Museum Haus Kasuya, Kanagawa

- Satoru Itazu demonstration at ‘Footprints’ exhibition, Museum Haus Kasuya, Kanagawa, 2016

- ‘Itazu Litho-Grafik Workshop’ Exhibition, Hikarie Shibuya, Tokyo, 2017 (partial overview)

- Itazu Litho-Grafik Workshop Exhibition Hikarie Shibuya, Tokyo, 2017 (partial overview)

- Satoru Itazu visiting the lithographic stone cellar of the State Office for Digitisation, Broadband & Surveying, Munich, 2018

I first met Satoru Itazu in the 90s while undertaking a half-year printmaking project in Japan as a Japan Foundation invitee. That project, entitled Tama Life 21 and purportedly looking to the twenty-first century, was the outcome of a long-planned desire to develop more artist-in-residence programs in Japan at the time. Four freshly minted studios across the Tama area of western Tokyo (for printmaking, weaving, sculpture, and ceramics) saw a handful of practitioners at each. As a painter and printmaker, I worked at the printmaking studio, meeting Itazu there one occasion when he visited.

Roughly midway between Tōkyō’s extremities—the orderly freneticism of the downtown wards and the mountain highs of its west-side expanses—sits the city of Chōfu. One of more than two dozen cities knitting the metropolis, it’s studded with a checklist of charms, setting it apart.

Enter Jindaiji, the Buddhist temple founded in AD 733, recharge in the myriad bucolic soba restaurants, or freshen up around Jindai Botanical Gardens, Chōfu’s Jindaiji Motomachi district is something to write home about. No postcard, reconnaissance report, or upload would be complete without mention of Itazu Litho-Grafik, however. This custom printmaking studio was set up by master printer Satoru Itazu in 1987 and has been quietly producing and publishing quality graphic art since.

While fine-art printmaking encompasses an array of techniques, Itazu Litho-Grafik, as the name suggests, is devoted exclusively to lithography. Not the commercially aligned offset lithography typically associated with automated presses and high-volume print runs servicing wide distribution needs, but limited-edition custom printmaking, defined by a hands-on approach to imagery conceived by artists and realised in graphic form.

Developed by German playwright and actor Aloys Senefelder in the late 1790s using Bavarian limestone, lithography employs a planographic process given the stones (and later metallic plates) from which images are printed are completely flat, one of the primary characteristics distinguishing lithography from other print media such as etching, engraving, and relief printing (including woodblock & linoleum). The fidelity to mark-making—particularly the hand-drawn and autographic—and its ability to realise full tonal ranges, nuanced detail, and carry either monochrome or colour are just some of its hallmarks.

In a nutshell, lithography (from the Greek lithos for ‘stone’) works by virtue of the antipathy between oil and water. Crayons, lithographic tusches and other water-repelling solutions are used to draw or paint imagery directly onto a freshly ground block or plate, after which the stone is treated with a prepared gum arabic solution to “fix” the image. After “curing”, the gum and oily mark-making residues are removed and things are ready to roll.

When printing, water-repelling hydrophobic areas attract ink applied by a roller, while inverse water-retaining hydrophilic areas repel it. The inked block and prepared paper are fed through the printing press with an even pressure, transferring the image to the paper before being peeled from the block. The stone or plate can be repeatedly water-sponged, inked and printed to allow for the creation of an edition, with stones able to be reground for reuse later on.

Itazu belongs to a breed of interlocutors with not just the requisite technical expertise, but also the disposition to work collaboratively with painters, sculptors, printmakers and artists of varying persuasions, allowing them to extend their creative output into the lithographic realm.

Becoming involved with lithography forty years ago, as an assistant at a Seattle litho-studio in the States, Itazu acquired a hands-on approach to the medium. After studies at the University of Oregon, he enrolled at Tamarind Institute in New Mexico in 1984. Regarded a lithographic Mecca, “Tamarind” (as it’s known) was founded in 1960 by June Wayne as Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles to create a pool of artisan-printers and act as a forum and incubator for modern-day lithography. The slight name change occurred in 1970 when it moved and came under the wing of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque in 1970.

Itazu let me know that he owes much of his ongoing involvement with the medium to Clinton Adams, Tamarind’s director during his time there. Itazu credits Adams’ insights and approach to lithography as a guiding light when setting up his own workshop in Japan.

Mokuhanga (woodblock printing) forms much of the graphic arts backdrop in Japan given the lineage of work in the medium—think Edo-period Ukiyo-e by the likes of Utamaro, Sharaku, Hokusai, and Kunisada, to work of the early twentieth-century Shin-hanga (new prints) and Sōsaku-hanga (creative prints) movements. Lithography was akin to a breath of fresh air given its rapid uptake in Japan during the early years of the Meiji restoration (from 1868), albeit much of its application being as predisposed to the utilitarian as to the aesthetic.

The Meiji government and the Japanese army turned to lithography in the 1870s, and in the 1880s private publishers increasingly took to the medium to suit their various purposes. Lithography was seen as high-tech, and efforts were made to import stones and presses into Japan and be seen as up to date. With colour lithography making its Japan debut in the late 1880s, the newfound palette and medium helped reinvigorate imagery once the exclusive domain of mokuhanga, including bijin (beautiful women), kabuki scenes, landscapes, and images of children, despite ongoing re-evaluations regards the aesthetic worth (especially vis-à-vis the “handmade” and “machine-made”) of much of the output.

The Stone Letter Project of 2017, in which Itazu played a key part, looked afresh at the early days of lithography in Japan from a contemporary standpoint. It involved students and an exhibition at Takarazuka University in Hyōgo. Recently-discovered lithographic stones of the late-Meiji to early-Shōwa periods, from the Kyōto factory of the Japanese Monopoly Bureau and featuring cigarette-pack designs for brands including Ikoi, Asahi, Shinsei, Peace, Hope, Iris and Corona, were laid across the gallery floor. The walls, awash with strike-a-light printed matter, evinced euphoric exhalations over the collaboratively made lithographs.

Back in Jindaiji Motomachi, the centrepiece of Itazu’s studio is his press, a made-in-Japan number by Shin Nihon Zōkei and which consumes its share of the space. A host of accoutrements, including about ten printing rollers of varying sizes and materials (some leather), along with a stash of inks, plates, stones and papers, not to mention the odd stray coffee cup, rounds out the scene. It struck me as a touch cramped on my first visit in the 1990s, though reassuringly so, in a way that lets you know things are going on, with the density and whatnot.

Sociable and affable, Itazu would meet artists—many then in their late-20s or early-30s—at gallery openings, art studios, artist parties and around town, some of whom would later find themselves producing their first lithographs at his setup. Given the relative scarcity of limestone, Itazu worked mainly with aluminium plates for the first 25 years. The gradual acquisition of stones from workshops and artists downsizing (or suffering from exhaustion) provided more latitude and scope.

In Japan, stone-based lithography utilising blocks is sometimes referred to as sekibanga (seki meaning ‘stone’; hanga or banga meaning ‘print’). A portion of Itazu’s growing collection of this hard stuff would sit at his front door for varying periods before finding its way onto the printing press, prompting some neighbours and passersby to wonder if he was venturing not just into the Neolithic-cum-lithographic age, though perhaps into the quarrying business as well.

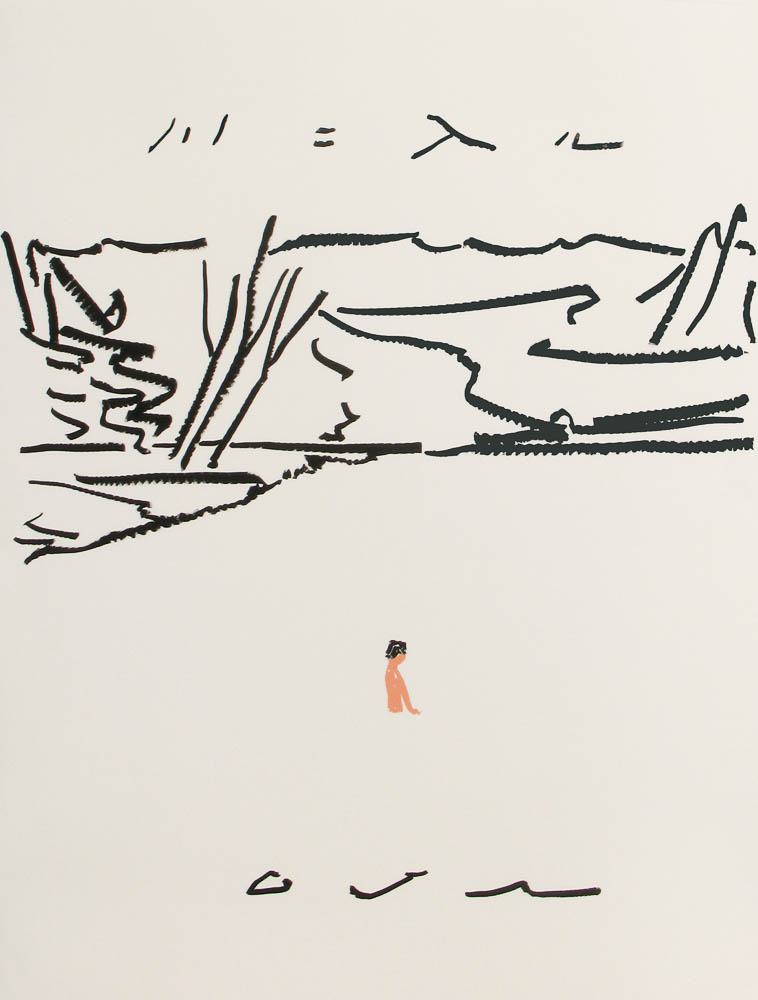

- O Jun, from the portfolio Kawa ni Hairu (Into the River) Lithograph, 2013-14 Izumi paper, 62x47cm / Edition of 7 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- O Jun, from the portfolio Into the River (Kawa ni Hairu) Lithograph, 2013-14 Izumi paper, 62x47cm / Edition of 7 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- O Jun, from the portfolio Kawa ni Hairu (Into the River) Lithograph, 2013-14 Izumi paper, 62x47cm / Edition of 7 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- O Jun, Wink Lithograph, 2008 Izumi paper, 385x285mm / Edition of 25 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

One portfolio comprising twenty separate lithographic images and making use of the stones was Kawa ni Hairu (Into the River, 2013-14) by O Jun (born Tokyo, 1956), with whom Itazu has been working since 1995. A painter who exhibits with Mizuma Art Gallery, Tōkyō, O Jun has produced an extensive body of graphic work at Itazu Litho-Grafik. One snippet relayed was O Jun’s idiosyncratic way of developing his monochromatic works: via the insistent use of brightly coloured crayons for preparatory drawings. Working between landscape and figuration, his faux naïf characters appear in random contexts and in states of existential serendipity. Earlier series include Tōzainanboku no Koko (Heart of North, South, East, & West, 2001), and Shusui (Autumn Water, 1996) after the similarly named WWII test aircraft.

Kaya Yaguraya, The Trinity, 2014

Lithograph, 2014

Arches paper, 370x275mm / Edition of 11

Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

Kaya Yaguraya (born Tōkyō, 1988) is a painter and graphic artist who puts lithography through its paces with her meticulous renditions of females, felines, flowers, and phantasmagoria, all with an impressive dexterity. Works like Hollow (2014), The Trinity (2014), and Black Cat (2014) offer enchanting glimpses into her somewhat dark-hued, elegantly crafted world.

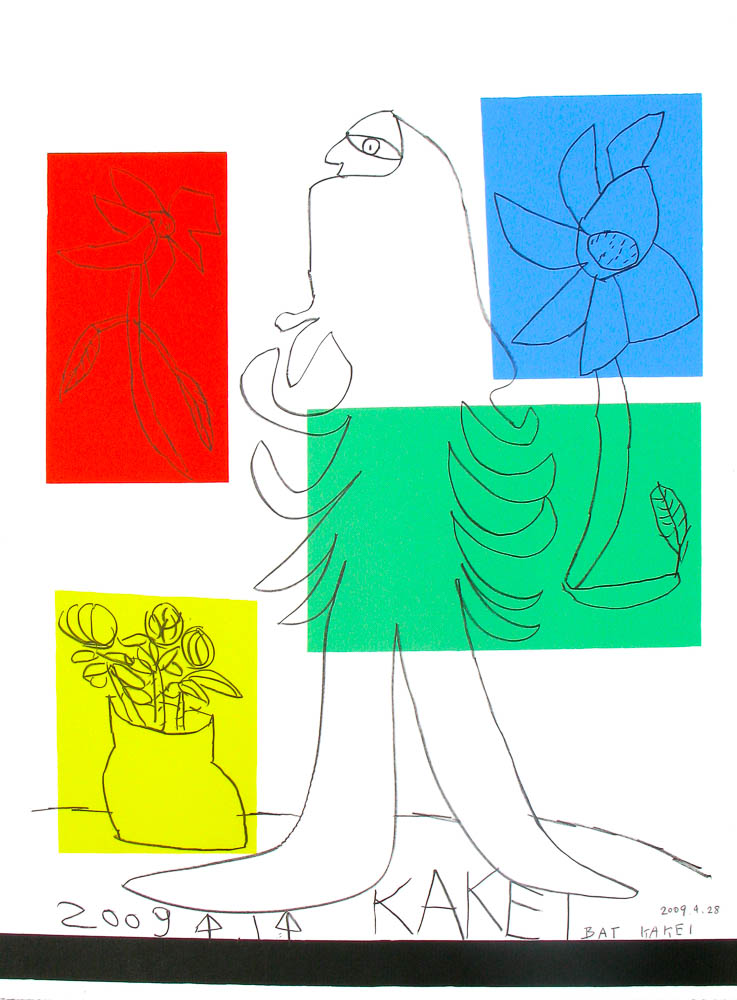

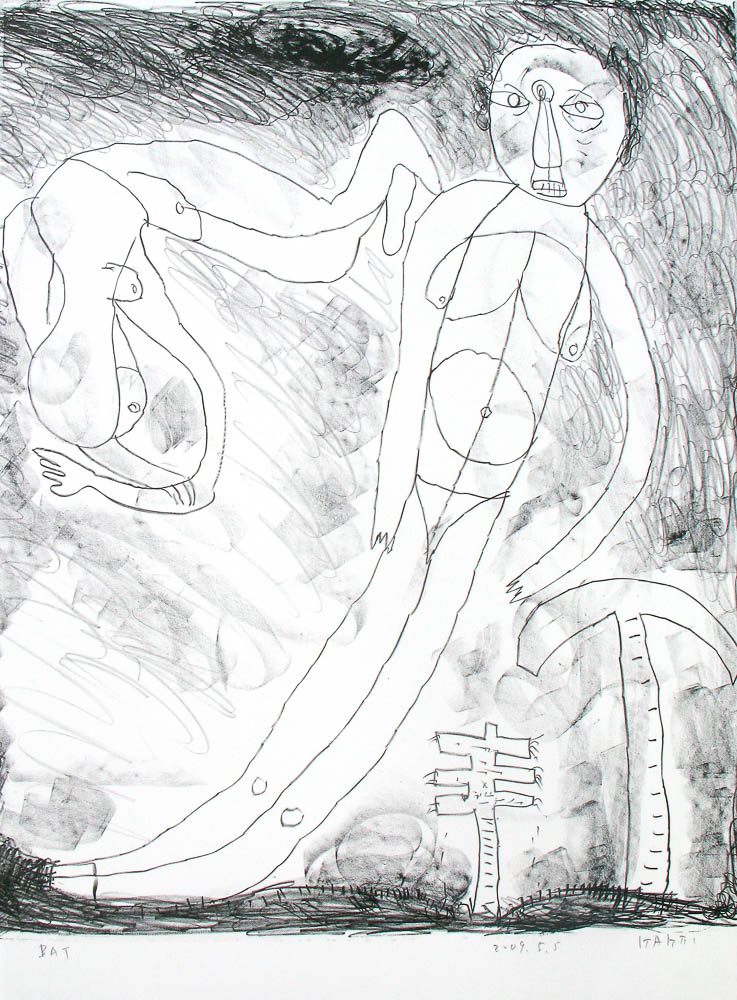

- Gorō Kakei, Girl Hiding Behind a Tree Lithograph, 2009 BFK paper, 76x56cm / Edition of 10 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- Gorō Kakei, Sky Walk Lithograph, 2009 Arches paper, 76x56cm / Edition of 10 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

- Gorō Kakei, Highway Lithograph, 2009 Arches paper, 76x56cm / Edition of 10 Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

Highway (2009) by sculptor Gorō Kakei (born Shizuoka, 1930), who represented Japan at the seventh Sao Paulo Art Biennial in 1963, is a good example of his scratchy, gritty renditions of urban thoroughfares and peopled spaces, and which exude a likeable, rough-hewn frankness.

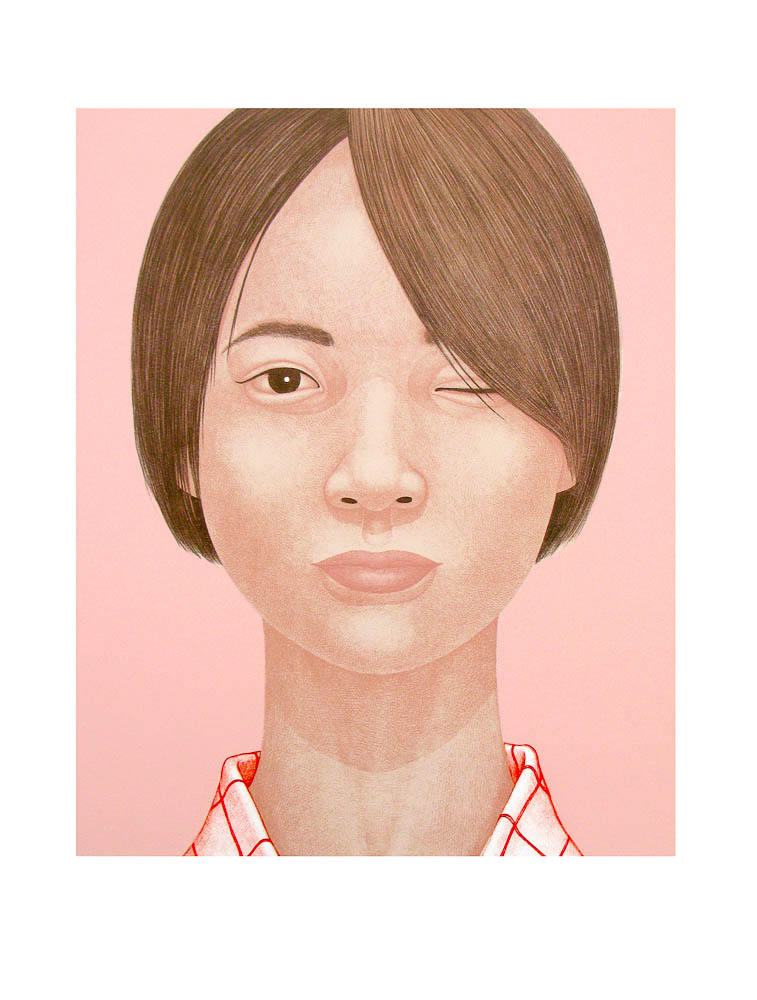

Takanobu Kobayashi, Portrait – One Eye

Lithograph, 2008

Arches paper 65x50cm / Edition of 30

Printed by Satoru Itazu at Itazu Litho-Grafik

Takanobu Kobayashi (born Tokyo, 1960) is another painter to have worked quite extensively with Itazu. His images of people and dogs present with time-frozen, hypnotic expressions, the directness of their gazes (or closed-eye frontality) kept in check by the technical restraint allied to their execution. His outdoor scenes, capturing moments of time and imbued with luminosity and soft-hued tones, have a mesmeric appeal.

A roll call of artists—home-grown and motley imports—have checked in at Itazu Litho-Grafik over the years. They embrace the breadth of representational, non-representational, and somewhere-in-between styles, and include Seiichiro Miida, Kumi Machida, Naoki Nishijima, Nobuhiko Nukata, Takashi Kitami, Tarō Morimoto, Katsuhisa Satō, and Yōichi Miyajima; and Australians Paul Saint, Narelle Jubelin, Michael Barnett, Joan Grounds, Sangeeta Sandrasegar, Catherine Chui, Caitlin Sheedy, David Nixon, Kyle Jenkins, Tiffany Shafran, and Stephen Spurrier.

The choice of paper used for editioning varies depending on the preferences of the artist and needs of the work, ranging from a wide selection of Japanese washi papers to European rag papers such as Arches and Fabriano. A consistent feature at Itazu Litho-Grafik is the size of the print run. Excluding trial proofs and the “all clear” B.A.T. (bon à tirer) print, editions generally consist of around 10-20 prints, with each sheet signed, numbered and dated after the printing is complete.

Itazu travels regularly, with trips to Europe the last few years, most recently to Germany to attend the Lithografietage International 2018 symposium at the Künstlerhaus Munich. They allow him to meet artists and colleagues, get new ideas and place his Japan-based activity in a wider context. His connections to the southern hemisphere go back to 2006 when he gave masterclasses at Queensland College of Art, Griffith University in Brisbane.

The large Footprints exhibition of 2016 at Museum Haus Kasuya in Kanagawa, spotlighting Itazu Litho-Grafik work and artists, and the simply-titled ‘Itazu Litho-Grafik (板津石版画工房)’ exhibition of 2017 at Hikarie Shibuya, Tokyo, provided further memorable viewing.

As if he doesn’t have enough on his plate, Itazu also teaches at Tōkyō University of the Arts, or the Geidai as it’s known and where, as Assistant Professor in its printmaking quarters, he’s able to impart his insights and breadth of experience to a very receptive and motivated group of students.

Further Reading

Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts

Author

Sydney-born Neilton Clarke first went to Japan in the 1990s as an invitee of the Japan Foundation to undertake an arts residency project, and where to date he has spent over two decades. He has written for Asahi Evening News, The Daily Yomiuri, The Japan Times, Art Monthly Australia, and British publisher Routledge among others.

Sydney-born Neilton Clarke first went to Japan in the 1990s as an invitee of the Japan Foundation to undertake an arts residency project, and where to date he has spent over two decades. He has written for Asahi Evening News, The Daily Yomiuri, The Japan Times, Art Monthly Australia, and British publisher Routledge among others.