Melissa Cameron, Juukan Tears (as installed at the John Curtin Gallery), 2021 2.6 x 0.1 x 4m.

Photo: Melissa Cameron

In conversation with Tanya Lee, Melissa Cameron learns about the life of the jewellery pieces that were salvaged from her Juukan Tears installation, as a personal mourning for the loss of sacred Aboriginal heritage.

In my work, Juukan Tears, I made a large wall hanging out of recycled corrugated iron, an unusual material which I sourced by tearing down part of my own back shed. From the by-products of making that piece, I assembled a series of jewellery works, entitled Juukan Tears Offcuts. Crafting the larger work was carefully orchestrated, minutely planned. Working with the offcuts was the opposite; once I shook their status of artefacts of the first process, I was free to feel my way, making a large array of pieces from the different remnants.

I do tend to be more of a planner, but that’s not why I was nervous about displaying the Offcuts series. The message of the large work is clear and carefully embedded into the design and the material choice for the work. The second series was less planned, rather it relied on the shadow cast by the larger work to deliver its meaning. Relegated to souvenir, my fears soon became that this series might venture into kitsch territory, or possibly even detract from the “main” work.

The left-hand-side of Juukan Tears contains a portrait of the Rio Tinto headquarters in Perth, with line-work “drawn” through the removal of material. This part is 4m tall and 1.3m wide; a size influenced by the gallery in which it was first installed. The right-hand segment makes use of the removed material from the left, which was cut out as 4,600 teardrop shapes, representing 10% of the 46,000 years of continuous history lost when the Juukan Shelters were destroyed in northwest Western Australia in May 2020. These were linked to make chains, designed to hang in a broken veil in strands of 100 tears and to be displayed next to the drawing.

To make the work I stitched together three separate sheets of recycled corrugated steel. One 3m x 80cm sheet was swallowed practically whole, while the other two sheets yielded some leftovers. These ranged from huge parts with a small bite taken out, through smaller segments with a few corrugations still intact, to tiny, jewellery-esque shards.

Melissa Cameron, Juukan Tears Offcuts – Brooches (jewellery series) 2021, dimensions vary (largest 197 x 41 x 5mm).

Photo: Melissa Cameron

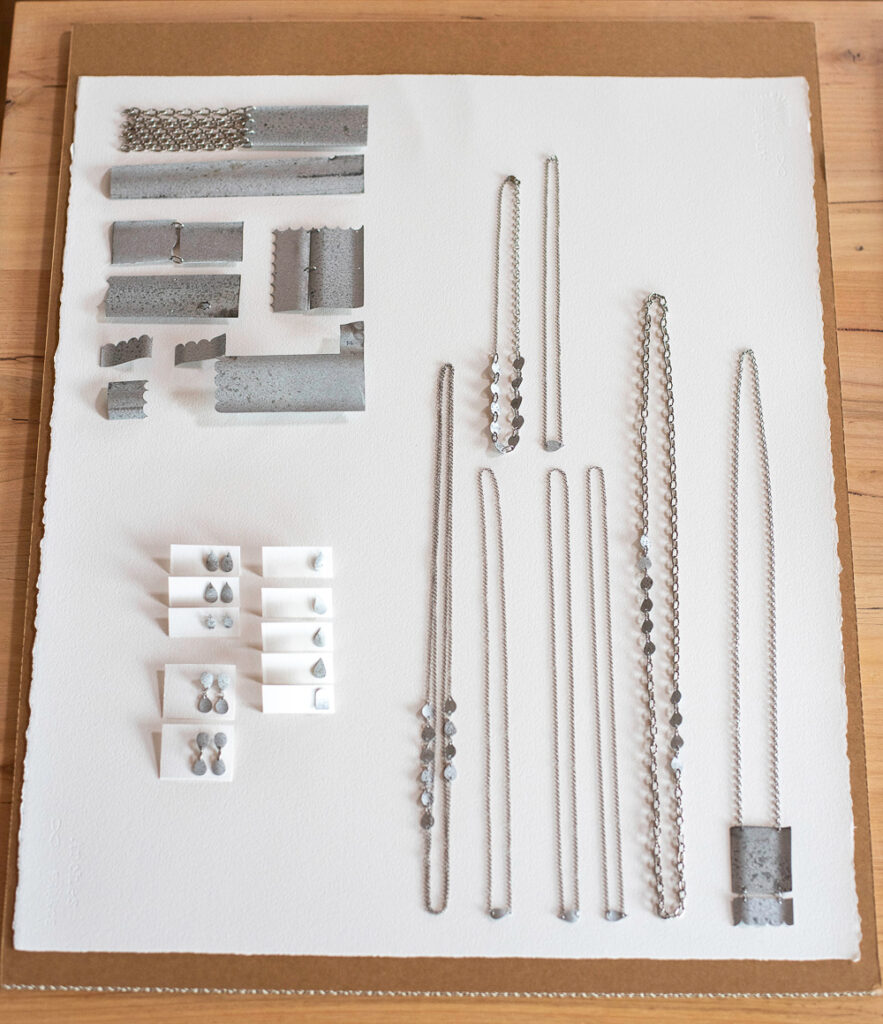

The Juukan Tears Offcuts jewellery works are made from the small-to-tiny leftovers. They are as they fell from the bench, with stainless jewellery fittings and chains added to make them wearable pieces. While they are made of leftovers, parts seemingly shed from the work on the gallery wall, they have been strategically worked to belong on the body. They are light and agile, and when viewed alone I feared this lightness could affect their meaning.

In order to find out a wearer’s opinion I reached out to the John Curtin Gallery, and Patti Belletty there kindly put me in touch with an ‘Offcuts jewellery purchaser. Western Australian artist Tanya Lee bought a pair of the ‘Offcuts earrings, so via email and a chat over Zoom I was able to find out her thoughts on them.

- Melissa Cameron, Juukan Tears Offcuts (jewellery series) as installed at the John Curtin Gallery gift shop, 2021, dimensions vary (largest 20 x 18 x 1.5cm on a 60cm chain). Photo: Melissa Cameron

- Melissa Cameron, Juukan Tears Offcuts (jewellery series) – Neckpieces, 2021, dimensions vary (largest 20 x 18 x 1.5cm on a 60cm chain). Photo: Melissa Cameron

- Melissa Cameron, Juukan Tears Offcuts (jewellery series) 2021, dimensions vary (largest 7.5 x 4.2 x 0.5 pendant on an 80cm chain). Photo: Melissa Cameron

Via email she told me:

“I’m based in the Kimberley at the moment, working at Broome TAFE [teaching art] and also in communities like Fitzroy Crossing. I also spent time in Karratha and Port Hedland this year for the first time. So I feel like my (relatively new) life sits very close to the ongoing violence of colonisation in the form of progress and development in the Kimberley region and that these things are very visible in day-to-day life.”

“I also thought about your pieces as potentially something akin to Victorian Mourning Jewellery—reminding me of something that is no longer present, it’s dead and can no longer be accessed. But also thinking about Mourning jewellery as a kind of penance or decision about the future that can no longer be without loss. Mourning Jewellery as a declaration to others that you may never be whole again or pure again because once your heart belonged to another. Maybe we can never be whole again because the destruction of Country eradicates the potential for belonging.”

I hadn’t made the link between mourning jewellery and the ‘Offcuts. Through that lens, the jewels condense and transmit the loss expressed in big work, and so contribute to its story in a unique way. Knowing the burden of the original story, and then adding the weight of the associations that Tanya had made, I wanted to know if she was still able to wear her purchase. We connected over Zoom for the next part of our chat*.

MC: “Have you worn them and do you have anything that you tell people about them? Or do you feel any responsibility to talk about them at all?”

TL: “Yeah, I wear them. They make me feel funny, like I’m not sure if I enjoy… Like what I said about mourning jewellery in my email. It’s something that’s really awful that I’m acknowledging when I wear them, but I think there’s a role for jewellery to do that. Obviously we don’t practice that as much anymore. But the potential for that… That’s what I think about when I am wearing them. And I wear them a lot. I teach art up here at TAFE in Broome, and I wore them and told my class about them and told them about your work.”

“… Like wearing a black armband, choosing to signify that your life is going on amongst this tragedy is a significant space to inhabit for a while. So sometimes I do feel strange putting them on, but I guess that association is exciting for me, that a piece of jewellery can do that, or a piece of art. When you wear something, you put it on your body, and it becomes part of your identity, and part of your identity that you are expressing to others … I think that’s a good thing, to project the way that we think about these things.”

MC: “I was wondering if it had been a smaller jewellery series that had been about the same topic but had been presented purely as a jewellery series would you have the same sort of relationship, or [are] the earrings that you bought a postcard of the larger object?”

TL:” … that idea of being able to take away part of an artwork definitely is what sells it to me. In a sense, I guess I see myself as a participant, like I’ve opted in to participate in the artwork, so less of a postcard and more of a return ticket.”

MC: “And given that you are more of a participatory-based artist, it came to you in a language … that you have a real understanding of and you can go ‘This is the extension of that piece into the world.’”

TL: “Yeah… The ideas that you are talking about, I can become a part of their practice, part of their expansion. Part of holding those thoughts. I can literally put those ideas on my body and hold them and think about them and continue to reflect on that, and in that way the artwork kind of grows, and we all become part of its story—anyone who participated in the same way that I did.”

I think that my concern at having such a direct relationship between the work on the gallery wall and the gift shop is still valid; it’s tricky terrain to negotiate. But thanks to Tanya I see that the understanding of what is on the wall can be enriched and elevated by what is on view in the cabinet closest to the door, and not just the other way around.

In the process, we might have discovered a third space, one that exists somewhere between the high and low in the craft hierarchy, that was only found by straddling the gap between gallery and the gift shop.

* our discussion has been edited for clarity

About Melissa Cameron

I’m an Australian-born artist with Anglo-Celtic ancestry, living on Whadjuk Noongar boodjar. I spent close to seven years living in Seattle, on the Duwamish lands of Turtle Island/USA, but I’m now back in my hometown of Perth, WA. My practice is centred on my deep empathy towards our human bodies, and the narratives that link us, and is influenced by my background in interior architecture and my studies in computer science. You can find new work in Bilk’s upcoming Solstice exhibition, and follow me at @melissacameronjeweller on Instagram, and my blog melissacameron.net my latest developments.

I’m an Australian-born artist with Anglo-Celtic ancestry, living on Whadjuk Noongar boodjar. I spent close to seven years living in Seattle, on the Duwamish lands of Turtle Island/USA, but I’m now back in my hometown of Perth, WA. My practice is centred on my deep empathy towards our human bodies, and the narratives that link us, and is influenced by my background in interior architecture and my studies in computer science. You can find new work in Bilk’s upcoming Solstice exhibition, and follow me at @melissacameronjeweller on Instagram, and my blog melissacameron.net my latest developments.

About Tanya Lee

Tanya Lee is a Western Australian artist currently living on Yawuru Country and working around The Kimberley. Her playful, cross-disciplinary practice uses sculpture, live performance and video to construct incongruous, and futile narratives with costumes, shelters and tasks. You can see some work at www.tanyalee-art.com And follow her workshops and other education-related things she does on instagram @tanyatechnicallyteaches (photo credit Yvonne Doherty)

Tanya Lee is a Western Australian artist currently living on Yawuru Country and working around The Kimberley. Her playful, cross-disciplinary practice uses sculpture, live performance and video to construct incongruous, and futile narratives with costumes, shelters and tasks. You can see some work at www.tanyalee-art.com And follow her workshops and other education-related things she does on instagram @tanyatechnicallyteaches (photo credit Yvonne Doherty)