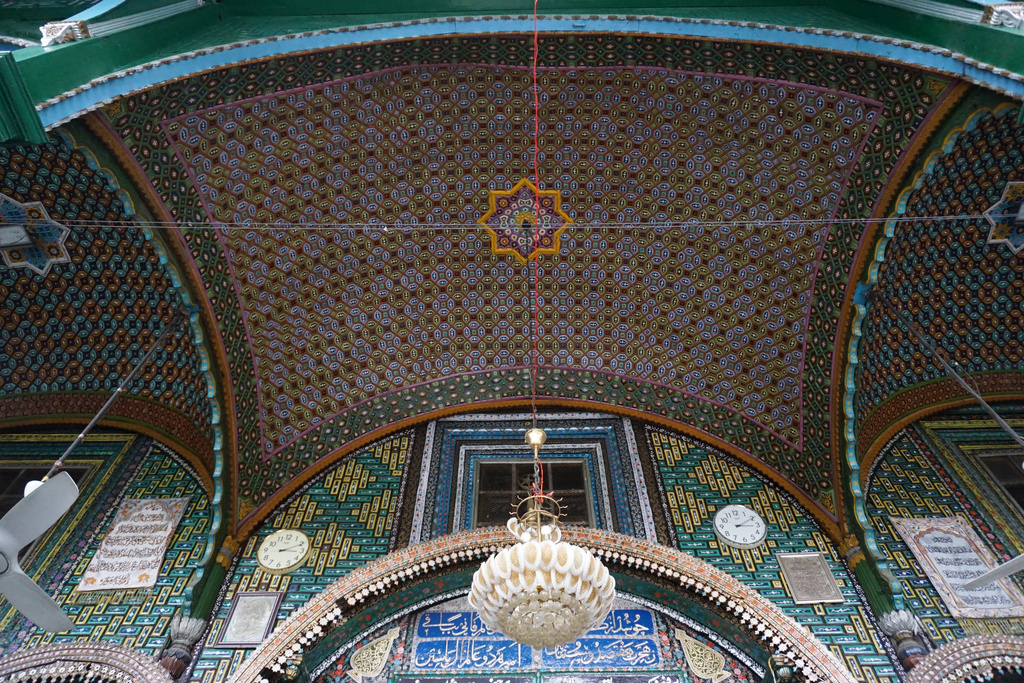

Khatamband ceiling, Shah-e-Hamadan Mosque. Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Photograph: Deepank Ranka (2022), Wikimedia Commons.

Shivani Kasumra celebrates the sublime ceiling craft now being revived in Kashmir.

Made by hand, Khatamband ceilings have adorned homes, shrines, palaces and the houseboats of Kashmir since 1541. In the Khatamband style of woodwork, ceilings of a closed chamber are made from thin panels of wood, cut finely into constellating geometric and floral patterns. Made of locally sourced deodar or cedrus deodara, walnut and pine wood, the word “khatamband” symbolises the stacking of polygons with gaj-patti or wooden beadings. All the myriad designs and patterns on patti and polygons are cut by hand.

Although its exact provenance in Kashmir remains unknown, there are two points of origin identified for this intricate craft. Some scholars believe that it was brought to the region by the Turkish military general Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, a subahdar or governor of Kashmir in the sixteenth century. Others believe it originated almost two centuries before this, with the Sufi mystic Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani (b.1312; d.1385), a central figure associated with the spread of Islam in Kashmir, as its progenitor. Both these narratives identify Central Asia, and particularly Iran, as its birthplace.

Metal nails are used sparingly and only at interlocking joints to hammer everything into place.

Not only are Khatamband ceilings painstakingly hand-crafted, but they also follow a laborious process of arrangement. Like pieces of a puzzle, the cut elements of these ceilings are held together by beadings and fitted with the polygonal shapes that compose the pattern, known as posh (flower). Bare elements such as the polygonal shapes are repeated across a surface and range from square-shaped muraba and rectangular sakhur to more complex forms of eight-spoked star hasta and diamond-shaped bita. Metal nails are used sparingly and only at interlocking joints to hammer everything into place. Because it is made entirely of wood, Khatamband ceilings preserve warmth and are an important architectural element in the cold, snowy region of Kashmir.

- Khatamband ceiling, Shah-e-Hamadan Mosque. Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Photograph: Mike Prince (2014), Wikimedia Commons.

- Khatamband ceiling, Shah-e-Hamadan Mosque. Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Photograph: Mike Prince (2014), Wikimedia Commons.

- Khatamband ceiling, Shah-e-Hamadan Mosque. Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Photograph: Mike Prince (2014), Wikimedia Commons.

- Khatamband ceiling, Shah-e-Hamadan Mosque. Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Photograph: Mike Prince (2014), Wikimedia Commons.

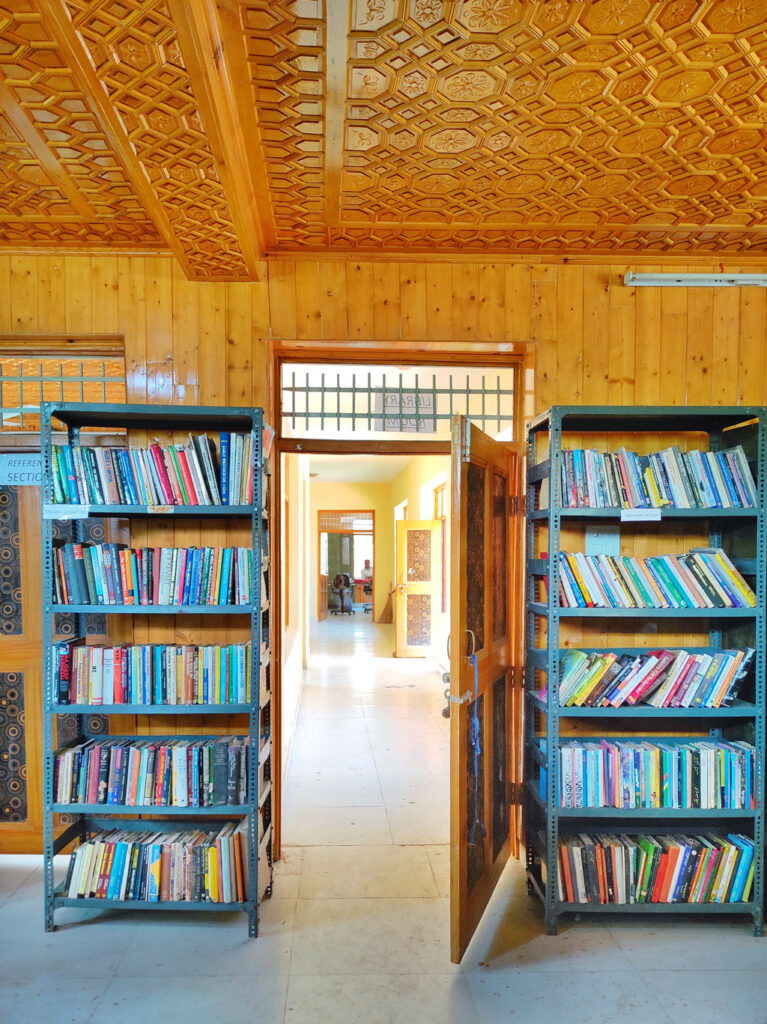

- Khatamband ceiling. Doru Shahabad, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Photograph: ThePoeticFrame (2022), Wikimedia Commons

Some of the most complex wood-carving patterns can be seen on the ceilings of the shrines Khanqah-e-Moula and Dastgeer Sahib in the valley of Srinagar in Kashmir. While the first is in the form of a crossed dome, the second features overlapping circles, tessellating pyramids and flowers.

A marker of luxury, these decorative ceilings were once restricted only to the upper crust of Kashmiri society. With the decline in royal and religious patronage, the craft too has gradually faded away. However, with the cost of labour reducing vastly due to decreasing demand, the craft has witnessed an unexpected revival. Now sought by the growing middle classes and nouveau-riche, Khatamband ceilings and artisans have been reintroduced to the world of interior design and luxury decor in Kashmir and abroad.

With over one hundred and sixty designs in its historical repertoire, present-day Khatamband artisans manage to reproduce around a hundred of these. With efforts by both government and private institutions, a degree of revivalist consolidation has also enabled not just the preservation of the craft, but its design history and knowledge.

References

Menon, Sreekumar, Maninder Singh Gill, Johanneke Verhave, and Vera Blok. “Conservation of Khatamband polychrome decorative ceilings.” ICOM Committee for Conservation, Theme: Sculpture, Polychrome and architectural Decorations: 913.

Sahni, Sakshi, Rawal Singh Aulakh, and Zarnain Fatima Ashfaq. “CRAFTS OF KASHMIR.” Himalayan & Central Asian Studies 27, no. 1 (2023).

Din, Towseef Mohi Ud. “A Study On The Different Delightful Craft Work In Kashmir.” The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 2, no. 4 (2015): 1211-3.

About Shivani Kasumra

Shivani Kasumra (she/her) studied history of art and visual culture at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Combining criticism, intellectual history, and visual studies, her MPhil dissertation examined speculative practices in contemporary art. She is presently enrolled in a PhD in the history of art and architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, USA.

Shivani Kasumra (she/her) studied history of art and visual culture at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Combining criticism, intellectual history, and visual studies, her MPhil dissertation examined speculative practices in contemporary art. She is presently enrolled in a PhD in the history of art and architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, USA.