- Plants I get my dyes from.

- Little Ruby – gives a deep purple dye when crushed.

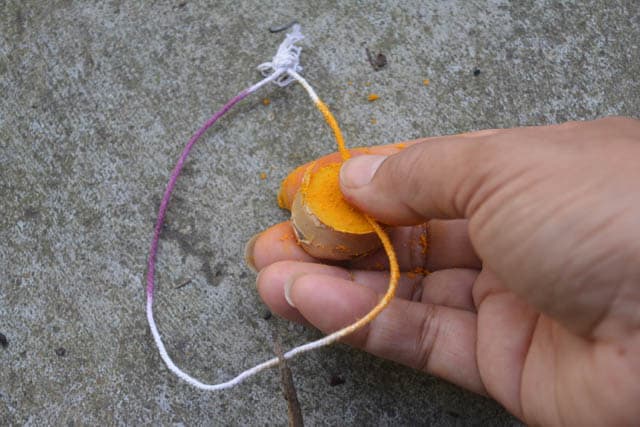

- twisted stirng dyed with Little Ruby and Turmeric.

- twisted stirng dyed with Little Ruby and Turmeric.

- Dried young sago leaf fibre used for grass skirts or bills – decorations on masks and drums.

- alternative belt and breast plate made from naturally dyed strings and shells – Papua New Guinea, Simbai area (Madang Province).

- Tapa cloth – just made and dried, ready for making into belt for grass skirt.

- Natural bilum – made with natural fibres and dyes from Papua New Guinea.

- Joycelin Leahy Painting Turmeric, Little Ruby and Charcoal on canvas.

- collection of portraits painted with natural Joycelin Leahy dyes.

- Joycelin wearing some of the bilas she made for a singsing – at 15, in Busu High School, Papua New Guinea.

A kamakom (magpie) broke out a high tune that echoed through the forest. In my village, Wagang, outside Lae, we were having a singsing (tribal dancing).

I was about to make my own grass skirt for the first time, but I needed to learn from the master. From the main road, away from the village, we could hear other magpies joined in the song and soon there was music on our way. Our shadows were nodding in front of us with every step we took. I was almost seven and have practised the weave and made the waistband, but now I was ready to make the whole grass skirt with Tinang. Tinang means mother. My grandmother was known by all three generations in our family as mother.

Tinang and I moved quickly ahead of the rising sun. This would be a typical day, when a child would venture into the forest or swamp with a master craftsperson. It was never a scheduled timetable nor a task set on the clock. It was usually a day that you needed something, and you had to make it. We carried little with us even for a day trip, except betel nut and a bush knife. Water and food, we always found on the way.

The smaller birds including sockwing, which is like a spirit bird, sang and chirped a welcome to the crispy morning as we arrived at our entrance. We entered the bush road towards Ampo Lutheran Mission, and where we would find the goodies in the wetland. Low harmony from rustling leaves and kunai grass blades reminded me and my grandmother of our ancestors’ origins and how this land has become ours because we fought for it. We discussed this history and began our own song in Yabem and sang with the birds. Tinang said it was important that we accepted the gifts from nature and respected the rhythm of life.

“You must never disturb the cycle because this is our source”, she said. As one of the heads of our clan and a known healer, my grandmother appreciated and nurtured everything from earth. She would be upset if someone recklessly cut eating banana trees, young coconut trees or sago trees. Such recklessness could cause a fight in the village. And no-one has ever shot a sockwing bird with an arrow or a slingshot. While walking with her, I read signs of broken leaves, footprints, tree bark markings and many important subtleties most people passed by.

Every step of the tribal life cycle was important because making a grass-skirt was only but one small part in the cycle.

“Everything we ever needed came from nature”, Tinang said. She would speak to me as she collected or pointed out each tree, shrub, vine, weed, leaf and tell me what their uses were as we walked through the thick wetlands, crossed open grassland, and waded through swampland. She also pointed out the landmarks and which piece of land belonged to which family. The markers can often be seen by a cluster of coconut trees or hot pink cordyline plants. Some plant markers had a heavy scent and you could not touch them because you could be put under a spell. There would be sections of land that was taboo, and we were not allowed to enter. We walked around such places, following paths and footsteps of others who respected the laws of our ancestors the same way. Most times, Tinang and I would sense a presence and just nod at each other as we passed. I remember feeling someone watching us or I was getting goosebumps and shivers. As my teacher, Tinang always assured me, the spirits had good intentions and were blessing us in our tasks. That meant, she said, that whatever we made would be amazing. Geyam Pwaluawe Kauckesa’s teachings came from her mother and grandmother. Our people had crossed the sea from Salamaua to Lae. The land was similar and the coastline under the forest provided all the craft materials, food, medicine and even magic.

My life as a child craftsperson was filled with colour, excitement and adventure. From 1970-1980, I spent a lot of time learning from both women and the men in my family.

To become a creator and a maker of crafts you had to be interested in it. But craft and art-making wasn’t something we could separate from our daily tasks in our family because everyone was gifted in making something or everything. Many bilum, grass skirts, masks and other traditional bilas (body decorations) are made using natural fibres, materials and dyes from plants. It was the way of growing up in the village in Papua New Guinea in those days and many children still have this privilege in parts of the country.

Many years later, I became a contemporary artist in Papua New Guinea and later in Brisbane, Australia where I live now. I found that I could not stay away from my love for natural dyes and patterns I had learnt from Tinang and my family. I began to experiment with various plant dyes I found and eventually sought information and advice from a horticulturalist friend who directed me to plants that had dye properties. These included what I knew as wampung—coleus, Yang—turmeric and new additions to my natural palette was alternanthera or little ruby.

I’ve also used basil opal, hibiscus, charcoal and pigment I’ve made with gum leaves. Anything natural I find in bushland that stains—I would try it in my art. I find the natural colours very soft and beautiful and it bounds me deeply to my roots. I use the natural dyes mostly on paper, but I have also used them on textiles and canvas. In my recent first ever PNG female fine art exhibition in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, I was very proud to show a collection of my art that I painted solely with natural dyes and a combination of plant dyes with watercolour.

Author

You can visit my website to see some more of these art: www.joycelinleahy.com or read some more stories on www.tribalmystic.me

You can visit my website to see some more of these art: www.joycelinleahy.com or read some more stories on www.tribalmystic.me

Comments

Thank you Jocelyn for sharing your story and reminding us in the most beautiful language of the need to be respectful of those the share the planet with.