Chloé Wolifson learns about the olfactory curating of Bharti Lalwani, which resulted in a scent canopy for an exhibition of Indian miniatures.

(A message to the reader.)

I first met Bharti Lalwani in Delhi, India in late 2016, as fellow art critics participating in a symposium. It was my first time visiting Delhi. The winter sky was perennially overcast and the leaf of every plant was covered in a fine beige dusting of pollution, as if shaken from a giant sieve in the sky. The mask that Lalwani, an allergy sufferer, wore to protect herself from the Delhi atmosphere stood out in those pre-pandemic times. The symposium concluded and we returned to our respective corners of the Asia-Pacific. From Sydney, Australia I followed online the activities of Lalwani in Pune, India, as she developed a self-taught independent perfumery practice. That mask had been guarding the precious tools of her new trade.

Raised in Lagos, Nigeria, Lalwani trained as an artist at Central Saint Martins in London, UK and The Sotheby’s Institute in Singapore before working as an art critic with a focus on the contemporary art of Southeast Asia. She now lives in Pune, India, where, without the aid of support networks, she has used her curiosity and critical nous to teach herself the fine craft of perfumery. Under the upended eponym of Litrahb Perfumery, Lalwani has created a space to develop fragrance and flavour into weapons in her critical arsenal. Regularly published newsletters reveal a boutique, bespoke and boundary-pushing practice which eschews the invented luxury and generalised Orientalism of mainstream perfumery in favour of strident experimentation.

Raised in Lagos, Nigeria, Lalwani trained as an artist at Central Saint Martins in London, UK and The Sotheby’s Institute in Singapore before working as an art critic with a focus on the contemporary art of Southeast Asia. She now lives in Pune, India, where, without the aid of support networks, she has used her curiosity and critical nous to teach herself the fine craft of perfumery. Under the upended eponym of Litrahb Perfumery, Lalwani has created a space to develop fragrance and flavour into weapons in her critical arsenal. Regularly published newsletters reveal a boutique, bespoke and boundary-pushing practice which eschews the invented luxury and generalised Orientalism of mainstream perfumery in favour of strident experimentation.

Early on, Lalwani discovered the limitations of the perfume industry—gatekeeping mirroring that of the worlds of art and academia with which she was already familiar. Undeterred, she pursued contacts and developed relationships which enabled her to experience materials she otherwise wouldn’t have been able to access, either due to geography, or her status as an independent practitioner. Lalwani’s practice is simultaneously hyper-local and global, reaching from the attar-wallahs and glass-makers of the local Pune shops, to US-based collaborations, and into Outer Space (a current Seasonal Perfume inspired by retro sci-fi).

In the course of her research, Lalwani uncovered a world of knock-off luxury fragrances, borne of the fact that mainstream perfumes use an alcohol base rendering them haram for Muslims. Oil-based versions of high-end perfumes, from Tom Ford to Chanel, are available note-for-note in Lalwani’s local shops for a fraction of the cost of the “real” thing. Following the formula for all knockoff merchandise, names have been tweaked just enough to avoid legal issues: Davidoff Cool Water, for example, becomes Water Cool at the attar-wallah. This workaround doubly explodes the exclusivity of luxury fragrance, revealing potential markets ignored by mainstream manufacturers, those whose faith forbids them to wear these mainstream fragrances, as well as those who cannot afford them. The discovery of these affordable scents opened a world of possibilities for Lalwani, presenting an alternative to pure aroma chemicals, a type of objet trouve with which Lalwani could play, and build her perfumed compositions.

Lalwani used the proceeds of her work as an art critic to fund her first major purchase of materials: a cache of essential oils which led to the development of a green chutney Edible Perfume™ which could be added to a soup or salad in the absence of the actual condiment. As a curious onlooker in the early days of Litrahb, I purchased another version of this fragrance, the Green Chutney wearable solid perfume. It arrived on a 37º Celsius day in Sydney, still holding its solid form, in a small copper vessel packaged within a delicate hand-stitched pouch. Limey and herbal, it was evocative in its specificity, a peppery condiment dressing the sweltering heat.

Time passed, and the pandemic took hold. Browsing international museum collections online, it became clear to Lalwani how much South Asian material culture is held in these collections but not on display, making it inaccessible not just to those to whom this culture belongs, but to anyone at all. Lalwani asked herself if there was a way through these locked gates, to allow herself and others a legitimate experience of their own cultural heritage, and to share this knowledge.

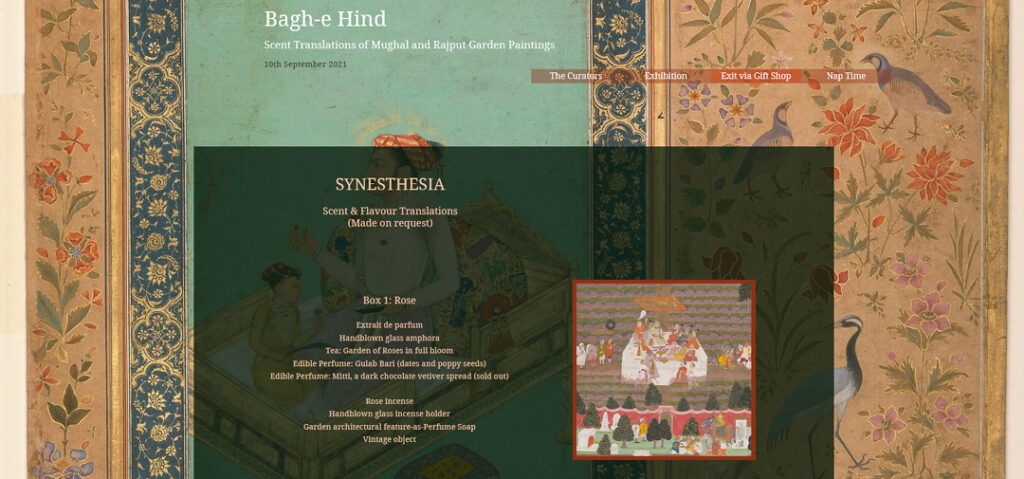

In the course of her research, Lalwani met Harvard-based academic Nicolas Roth, and in 2021 the pair launched the online-based multi-sensory exhibition, Bagh-e Hind: Scent Translations of Mughal and Rajput Garden Paintings. Through Bagh-e Hind (the title of which refers to gardens of the Indian Subcontinent), the curators have created a unique model bringing to life seventeenth and eighteenth century Hindustani garden paintings from public collections using scent translations, with the aid of objects from public and private collections, flowers growing in Roth’s garden, and music, under several scented canopies: Rose, Narcissus, Smoke, Iris and Kewra.

It all started with a painting by Nanha, The Emperor Shah Jahan with his Son Dara Shikoh, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album verso: ca. 1620, from the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. While the decorative garden border of this work may be of secondary importance for scholars, Lalwani was immediately drawn to its encoded combination of plants and pollinators. Saffron, stonefruit, and honey all swirl around each other, suggesting a scent therein: Bagh-e Hind. With this work as a starting point, the exhibition then unfurls online under its five scent-canopies.

Roth’s reading of specific texts on gardening in various South Asian languages and dialects has uncovered subtle differences between plant varieties. The ubiquity of some of these plants was such that they appear as metaphors in Persian and Urdu poetry, examples of which appear in Bagh-e Hind. This degree of specificity breaks down the generalised exotic aesthetics that have characterised Orientalism in the past and continue to do so in the commercial fragrance world and elsewhere.

Roth’s reading of specific texts on gardening in various South Asian languages and dialects has uncovered subtle differences between plant varieties. The ubiquity of some of these plants was such that they appear as metaphors in Persian and Urdu poetry, examples of which appear in Bagh-e Hind. This degree of specificity breaks down the generalised exotic aesthetics that have characterised Orientalism in the past and continue to do so in the commercial fragrance world and elsewhere.

Recognising that the strictures of academia may not always leave space for elevating and fully enjoying the poetic and the sensory, Lalwani has extracted these elements from Roth’s research, curating and presenting an accessible, aesthetically rich encounter. This includes showing imagery of her perfumery work in progress, shining a light on a normally mysterious and opaque process whose secrecy feeds luxury and exclusivity.

Unique edition glass bottle in the collection of Nicolas Roth, commissioned for Bagh-e Hind by Bharti Lalwani, 2021; photo courtesy Bharti Lalwani

One is invited to meander through the online exhibition, encountering its paintings, objects and poetry snippets at a leisurely pace accompanied by music chosen by the exhibition’s Sound Designer, Uzair Siddiqui. Images can be viewed with or without captions and exhibition didactics alongside. Translated snippets of poetry are hidden, easter egg-style, between the images, and each page features a record of discussions between the two curators, taking the audience with them on the journey of building a fragrance based on the depicted garden. The pinnacle of the exhibition is the Synesthesia Boxes, containing the finished scent and flavour translations into various forms, which are available for purchase.

- Installation shot of Bagh-e Hind: Scent Translations of Mughal and Rajput Garden Paintings at The Institute for Art and Olfaction, Los Angeles, 2022. Image courtesy IAO

- Installation shot of Bagh-e Hind: Scent Translations of Mughal and Rajput Garden Paintings at The Institute for Art and Olfaction, Los Angeles, 2022. Image courtesy IAO

- Installation shot of Bagh-e Hind: Scent Translations of Mughal and Rajput Garden Paintings at The Institute for Art and Olfaction, Los Angeles, 2022. Image courtesy IAO

In 2022, a physical version of the exhibition took place at the Institute for Art and Olfaction Los Angeles, with the lead paintings in each section of the exhibition replicated at scale, allowing audiences to engage up close with these works in a manner that would not be possible with original artworks in a traditional museum setting. The process of recreating the exhibition across distances was collaborative and imaginative, with local independent perfumer Miss Layla (of fūm Fragrances) commissioned to recreate each fragrance for the occasion.

Gate-keeping happens but the qualities of scent allow it to waft out from between the bars of those gates, and from over the walled gardens of art, academia, and fragrance. Bagh-e Hind allows us to imagine how those paintings, despite being kept locked in storage, can dissolve off the page, flow into the atmosphere, to pollinate and propagate a new garden of understanding.

Further reading

Bagh-e Hind reading list

Litrahb Perfumery journal

About Chloé Wolifson

Chloé Wolifson is a Sydney-based independent arts writer, researcher & curator whose work includes reviews, catalogue essays, and reports on exhibitions and art fairs throughout the Asia-Pacific. Her writing is published in mastheads and magazines across the region and she has curated exhibitions and public programs in public, artist-run and commercial spaces.

Chloé Wolifson is a Sydney-based independent arts writer, researcher & curator whose work includes reviews, catalogue essays, and reports on exhibitions and art fairs throughout the Asia-Pacific. Her writing is published in mastheads and magazines across the region and she has curated exhibitions and public programs in public, artist-run and commercial spaces.