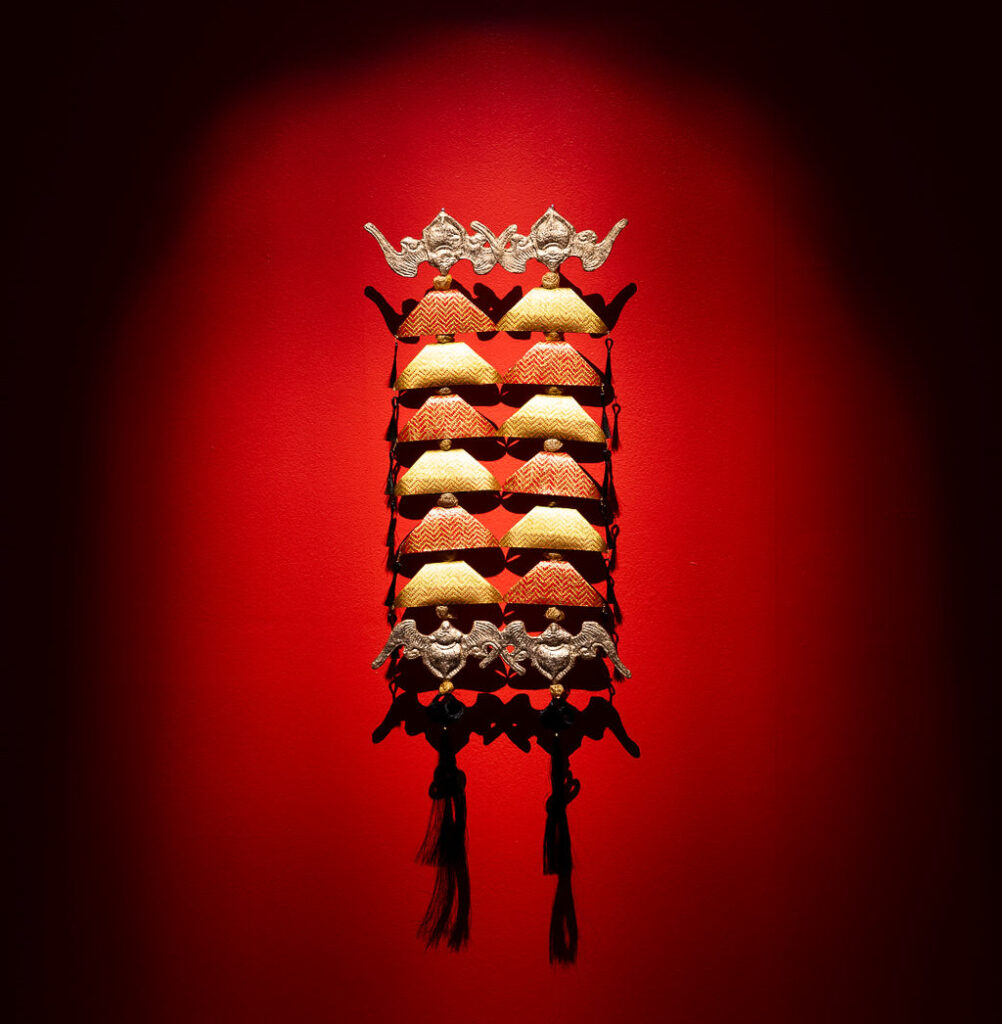

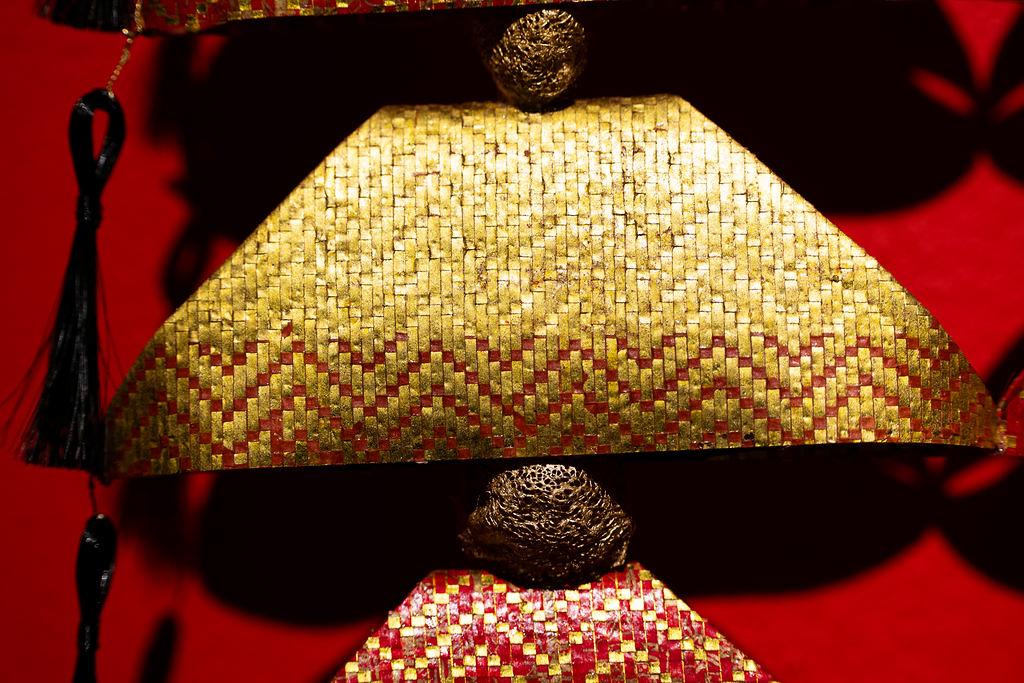

Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

Jacky Cheng traces the woven Joss paper objects in her Indian Ocean Craft Triennial exhibition back to Malaysia and her fraught role as a dutiful daughter.

(A message to the reader in Bahasa Malaysia.)

(A message to the reader in Mandarin.)

(A message to the reader in English.)

Jacky Cheng’s Indian Ocean Craft Triennial exhibition Lucky Charms created an atmosphere in the gallery resembling a temple. Many of the works were made from Joss paper, which is used for devotional purposes in Taoist services. We ask Jacky about the relationship between being a contemporary artist and her more traditional upbringing in a religious household.

✿ What’s your story about becoming an artist?

Both my parents worked long hours. So I spent a lot of time with my grandmother. Rituals and practices were pertinent every day, and there was never nothing to do. I was predominantly tasked with folding Joss papers because that was the easiest task. So that was my understanding of making art because that was the only time that I actually got to use my hands to make something and sit very still.

But I knew at a very young age that I had the tenacity to engage in making and doing because it’s like a muscle memory: when you’re given a task and you do it. And I was very afraid of my grandmother because she’s the matriarch of the family. It felt like play but with serious outcomes for the deities.

Then, of course, there came a time when I rebelled. There was never really a place for me at home at that time to express my true intentions. I have to study hard and find a profession that will fit me rather than become an artist. The word artist is just not visible within the family because you do art as a form of relaxation, or you do art because the school has asked you to engage in art, but not so much about art as a profession or a sense of purpose in itself.

I had a conversation with my father when I was 17 because I suddenly realised that my role as a female, a daughter, a sister, a woman, was challenged by my family’s expectations to take retail or service trade and find a partner and have kids. But it also meant at that time, my last name, Cheng, is not carried through. My dad said, “I will not invest in you because you will lose the surname one day.”

So I rebelled. I thought that all these years, you wanted me to study hard, and it meant nothing for the family. It crushed me.

I went into architecture because I knew that it was reputable, it’s something that my father would agree to. But he didn’t agree because he stuck with his guns about not letting me continue my education. I begged my brother to talk to my dad, and they came up with the proviso that they will let me continue education, but I must come back with high distinctions in every subject.

I studied four years in Malaysia, and then you’re meant to finish off a final two years at Curtin University. But I went to the University of New South Wales because I didn’t want to be amongst my classmates. They had transported the whole class to Australia, and I was still in the same group.

I wanted something different. I knew that the chapter needed to end. I came over to Sydney to study architecture and graduated in the top 10 of my class with first-class honours. I showed my dad, and he thought that I was going to move on and become an architect. Very secretly, behind the scenes, I had enrolled in all art electives. So, I gained a lot of those skills. It was just a way of exploring ideas, of making and doing.

I was approached by one of my lecturers to do some special tutoring at the university. So I took on that job and then worked part-time at an architecture firm.

✿ How did you come across to Broome from Sydney?

I was working at the Australian Geographic store. I love kids. A family offered me a position to become a babysitter. So months later, they said, Look, we’ve got a house in Broome. Why don’t you come to Broome? So I said, Yes. I’d never heard of Broome.

It was a two-week holiday. By the third day, I thought, there’s nothing much for me here. I will just go back to Sydney and continue what I was doing. But then it proved me wrong. I met a local lady, and we started chatting. She started telling me stories about Broome and her mixed-race family. She had grandparents of mixed Japanese, Aboriginal, Scottish and Malay descent. It just didn’t compute in my head. I realised that I knew nothing about Australia. So she invited me over to a house, and I got to know the relatives. I realised that I’m in Australia, and I’ll probably never be brave enough to do anything else after that. So I decided that’s where I wanted to be. I had nothing to lose. So, 19 years later, I’m still here.

✿ What appeals to you about Broome

Broome punches above its weight: the people, the history. The weather is not as disgusting as everyone reports. I found common stories from my native identity here in Broome – and realised that I never really left home but embraced a slightly different belonging. I just feel like I’m constantly morphing myself around whatever is happening around Broome.

- Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

- Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

- Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

- Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

- Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

- Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

- Jacky Cheng, Lucky Charms installation, 2024, Fremantle Arts Centre, Indian Ocean Craft Triennial; photo: Bo Wong

✿ Moving towards the installation in Fremantle in IOTA, what were the key ideas behind it?

It’s a body of work that examines the psychological comfort of rituals within our lives, like throwing salt over your shoulder or touching wood. The work was inspired by my grandmother and her moon blocks. Moon blocks are for contacting spirits, either ancestral or celestial. But my grandmother also used them as a very important decision-making tool. Sometimes it could be up to three times a day. She’s got this anxiety and uses them to build confidence.

The work challenges the ideas of Joss paper as something taboo. So, I recomposed the material into a different object. Everyone looked at it as an object of beauty and no one asked me what paper it was.

✿ How does this work in a gallery relate to your experience of the temple?

I think temples are very much of a sensory thing. I wanted to simulate exactly what the intentional placement of all the works meant. You feel a sense of attentiveness, inquisitiveness, and also a private surveillance of objects, much like a private temple. It has an aura.

When I go home and visit my dad, he says, “All right, tomorrow we’re going to see your grandmother”. You get fresh fruits and fresh flowers. Everything needs to be fresh. I have to remember to bring patterned clothes, rather than my usual monotone. So the next morning, we’ll go to the temple together. The moment you’re in front of the temple, at the gates, you start bowing. There is a dance to it.

✿ Is there a shrine in the family home where you make prayers or offerings?

The female matriarchs in the family have all passed away. We used to have such elaborate celebrations. It was such a festival. When my grandmother passed away, they closed up the entire road and spent three days and three nights celebrating. There were performers with stilts, walking up and down. Those are the days that really formed me in the way I am today. I yearn for those moments. I fear that nobody in the family wants anything to do with any of these ceremonies anymore because it was such an elaborate process. I don’t want it to die.

✿ That seems ironic, Jacky, that you leave your family in the kind of traditional life in Malaysia to embrace the freedom of a modern, secular society in Australia and get to Broome, and then what you see is that life declining where you came from, and wanting to somehow arrest the decline.

It’s as so often is the case, you know, when it’s been like the frog, you know, boiling in the saucepan that doesn’t really know it’s doing it. The traditions gradually decline. They get smaller. The time spent is less and less. So if you’re in the midst of it, perhaps it’s not noticeable, but for you at a distance, coming once a year or whatever, it might be more radical what you’ve embraced the other side.

I finally read the book by Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands. It was banned in Malaysia. I related to the sentimentalities of the imaginary homeland. I don’t feel that anger towards my father anymore because I finally understood what he was trying to say: you’re the matriarch of the family; you’re the next in line to continue this. Hence, don’t bother about all these other types of education.

At that age, I couldn’t understand. My father is a lexicographer who produces and translates dictionaries. He’s a liberated man, but why would he not want his daughter to be educated? I understand now.

✿ Is there any other story that you’d like to share about rediscovering traditions?

Back home in Malaysia, when I was about 11 years old, we had a courtyard. Every year, when the sun is harsh, my grandmother takes a suitcase out with the lid open, and she rotates her clothing. I never really paid attention. But one year, I decided to find out what’s really inside the suitcase. She saw me going close to it, so she came after me and smacked me in my back and told me to go away.

Six years ago, I told that story to my mom. She goes, “Oh, that’s her funeral clothing. When one turns 60, you would have completed your life cycle and that’s when you start preparing for your funeral clothing.” And I also then found out that my grandmother wore five silk tops and seven silk bottoms, because the tops represent children and the bottoms represent grandchildren. So you must always wear more numbers than you would on top, and you have to wear silk because it represents a smooth transition to the afterlife.

I realised that my mom never said anything about it. I asked, “Well, have you prepared your funeral clothing?” She said, “Yes.” I said, “When is anyone ever going to tell me any of this?” My mum’s excuse was the fact that I live in Australia and I probably don’t want to practice this. Why should I know about it? So just move on with your contemporary life.

So, I took that opportunity. I said, “I want to investigate this notion of the afterlife, or even the end of life, of preparing for it because it’s a very beautiful notion.

About Jacky Cheng

Jacky Cheng was born in Malaysia of Chinese heritage. She received her Bachelor of Architecture (Honours 1) from University of New South Wales, Sydney. She is an artist, a facilitator and an art educator based in Broome, Western Australia. Visit jackycheng.com.au, follow @jackychengart and like facebook.com/jackychengart

Jacky Cheng was born in Malaysia of Chinese heritage. She received her Bachelor of Architecture (Honours 1) from University of New South Wales, Sydney. She is an artist, a facilitator and an art educator based in Broome, Western Australia. Visit jackycheng.com.au, follow @jackychengart and like facebook.com/jackychengart