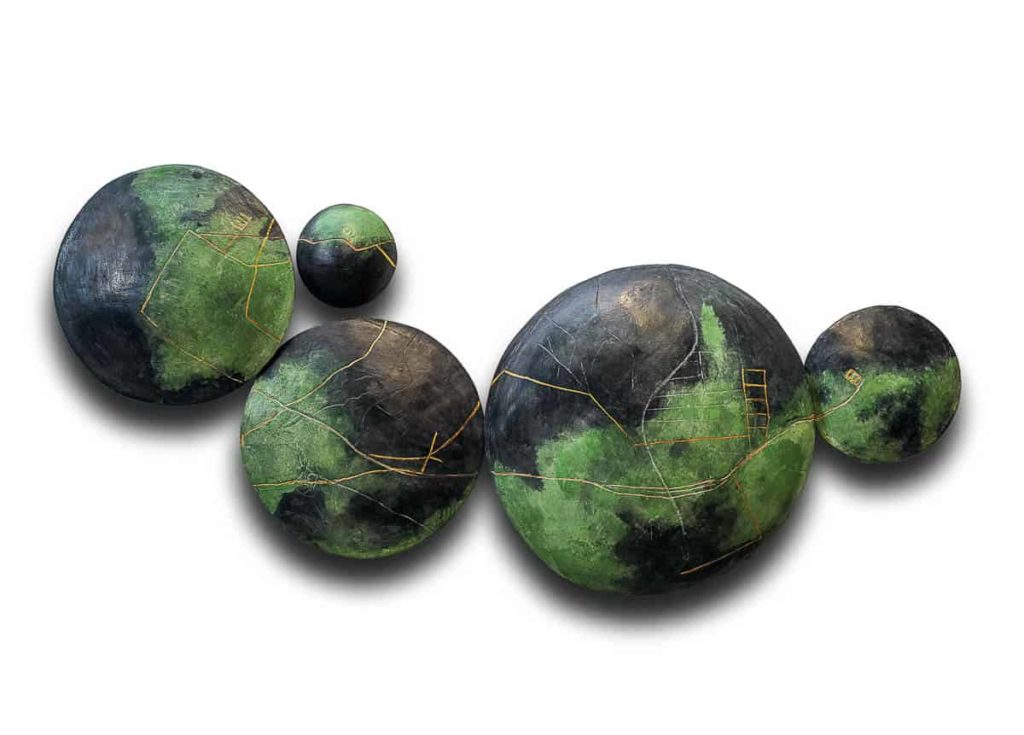

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, Mappa Mundi series: Green, 2017, earthenware, gold dust, 18 x 45 inches

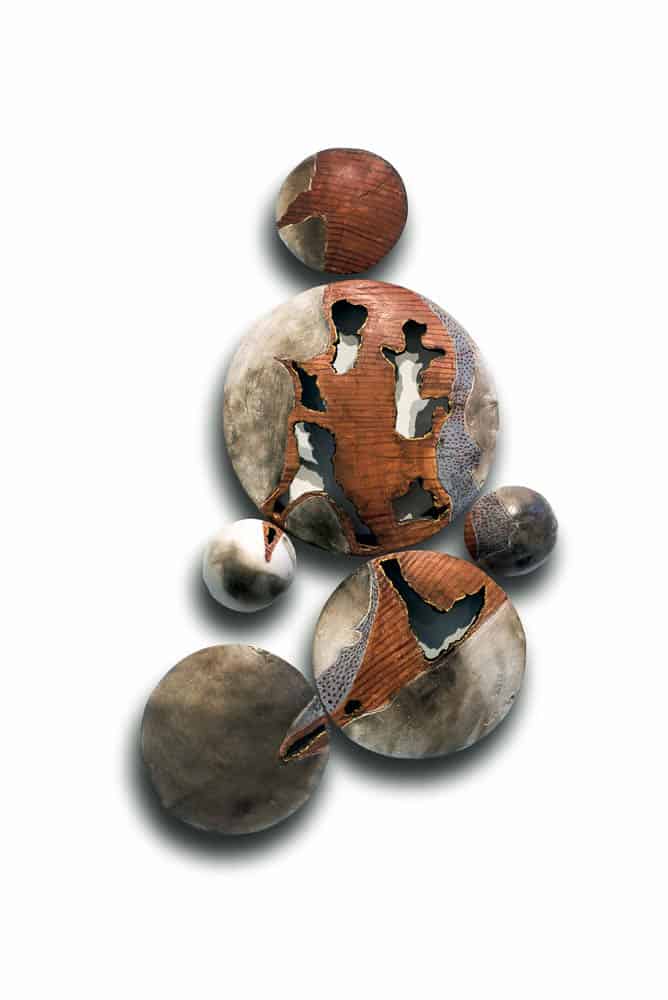

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, Mappa Mundi series (Black/White), 2017 Stoneware, 17 x 26 inches

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, Mappa Mundi series, 2017, earthernware, smoke-fired terra sigillata and gold dust 20 inches diameter each

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, Mappa Mundi series (7 islands), 2017, earthenware, smoke-fired terra sigillata and gold dust 37 x 34 inches

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, In the Shadow of the Trees, 2017, stoneware, shelf, light and shadows size variable

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, Rolling Pins, 2017, porcelain, glaze, powder coated metal rack, vitrine Vitrine size: 48 x 18 x 32 inches Love: Luck: Life: Health: Heart : Fame | Love, Fate, Give, Live, Health Wealth

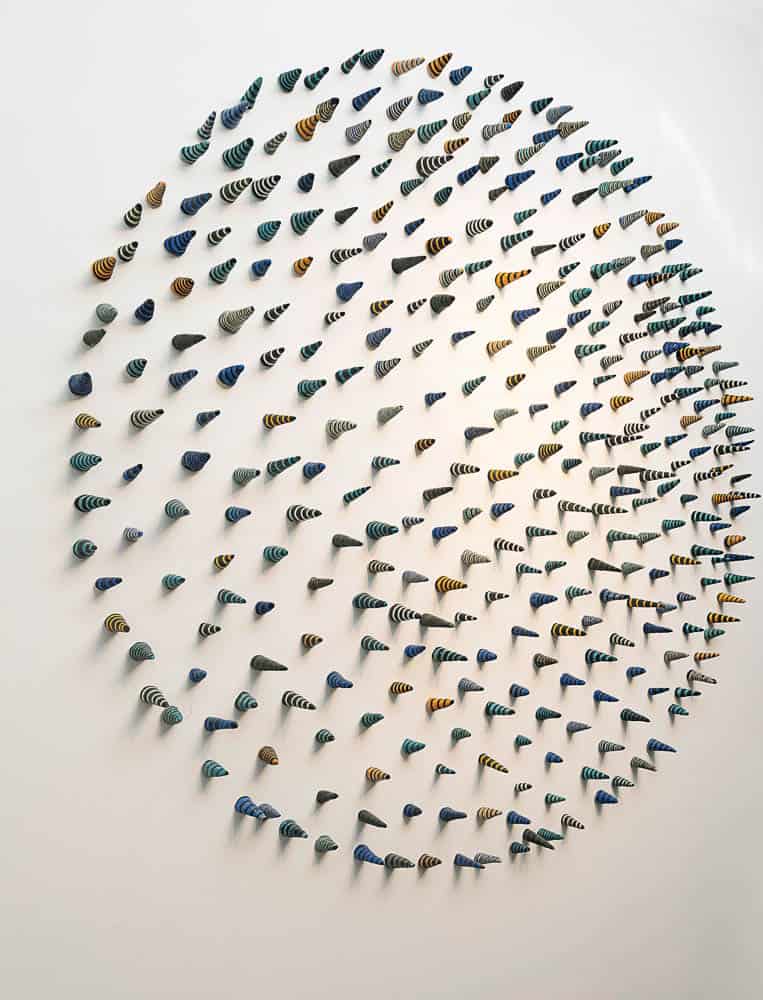

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, Germination, 2017 Stoneware, glaze 72 inches diameter

- Madhvi Subrahmanian, Germination, 2017 Stoneware, glaze 72 inches diameter

Madhvi Subrahmanian’s recent ceramic sculpture-installations and assemblages mark the expansion of her studio practice into social space.

At the entrance to her exhibition at Chemould Prescott Road, Mapping Memory, we come upon a small garden that seems to have blossomed around her tree sculptures. This is the outcome of an experiment, in which Madhvi invited her viewers to participate and share in her artistic labour. Responding to the invitation, they fashioned their own trees from sticks and balls of clay, in a modest workspace carved out of the exhibition area. Some of the trees aspired towards naturalism. Others were amateur delights. Yet others, like Peter Pan, were unsure whether to be a plant or a full-grown tree. These informal creations—unbaked, unglazed, ready to crumble—were placed around the composites of trees, houses and phantom roads that are the artist’s sculptural objects. While Madhvi’s gesture of hospitality was exemplary for its inclusiveness, was she also questioning the role of the ceramic sculptor in contemporary times, and charting the future direction of her practice?

I would argue that a certain formalist abstractionism inheres within the art of the modern ceramicist, whether practised in India, America, or Japan. Indeed, the closer one looks at these three regions, the more strongly one is reminded that modern ceramicists in each region have been nourished by the work and thought of their colleagues in the other two—which makes for a transcultural idiom that, despite particular regional emphases, is premised on a shared taste for primordial, archetypal impulses. These grand impulses have tended to fetishise an art form whose origins lie in humble everyday materials and processes geared to melding the aesthetic and the functional. By embracing sociality, Madhvi attempts to break the spell of the studio- shaped fetish object and restore the ceramicist’s art to the circuits of everyday life, in which the viewer does not remain a passive consumer but organically contributes to the process of art-making.

In her evolving practice, Madhvi has endeavoured to disturb such formalist abstraction. She has experimented with a range of processes, both formal and informal, and allowed the factor of chance to gamble against set protocols; she is a partisan of low firing, hand-building, smoke marks, cracks, holes, cavities and surface impurities. She favours mandala-shaped assemblages, those fail-safe guarantees of holistic selfhood, but is also keen on spirals that spin away from the centre and find their own trajectories. She does not differentiate between clay and skin. She kneads and “grows” seeds, pods, cones, trees; she once made a mould of her pregnant belly.

Madhvi is a comrade and co-conspirator of clay; time and gravity are her adversaries. She records the shadows of arrow-shaped roads; time wipes them out. She challenges gravity; she builds high, higher, not out of hubris, but because she knows that “if you push clay against its will, it pushes right back”.

Mapping Memory presents its viewers with a contradiction: How do we apply the cartographer’s precise tools to something as slippery as what is remembered and how it is remembered? In the struggle between humankind and nature over limited resources, how does memory fare on the scorecard? If time and gravity oppose her, the artist’s obvious allies in this body of work are shadows and light, which point up the tension between naturalia and artificialia. Roads crawl up her ceramic tree sculptures, striating them with zebra crossings. In this territorial battle, the tree does not let the building forget who is the interloper. It fuses itself with the building, making love or war, depending on our vantage point.

Madhvi cannot resist the magical power of the handprint, the most ancient form of presencing the human self. In adjacency with the handmade clay trees made by the viewers, she has composed a large assemblage of cow dung cakes, each one rendered in pristine porcelain, a medium described by the pioneering British potter Bernard Leach as the “ultimate refinement of pottery”.The sanitised coolness of porcelain is pressed with the warmth of deeply etched fingerprints, reminding us of women’s labouring hands. But is Madhvi extolling the virtues of purity, whether of the definitive expressiveness of this ceramic medium or of the sacred status of cow dung in Hindu ritual? Or, closer to the bone, is she questioning the claims of the gau rakshaks, the cow vigilantes who have in recent years brutally lynched Muslims and Dalits in the name of protecting the sacred cow.

The (in)organic porcelain cow dung cakes frozen on the wall by a Midas touch remind us painfully of how the cow has been fetishized by the forces of Hindu majoritarianism to incite communal and casteist tension. We turn a corner: an interactive installation invites viewers to leave low-relief word-prints on a bed of sand. Using porcelain rolling pins, we roll out a utopian future where “luck” and “love” will not fail us. Along with the words, a recurring fingerprint makes its presence on the sand. Does it belong to Madhvi who, like the prehistoric shamans, is leaving her mark as an artist-healer on her work? Madhvi knows that the world is too vast to be moulded into decipherable shape with her migrant fingers. Over the years, she has called three continents home, living variously in India, Singapore, the USA, and Germany. In her sculptures, she turns cartography into fiction, which perhaps is the only real way home. Her personalised maps of her past and present itineraries in Singapore and Bombay are installed like shields on the wall: protective gear to ward off the caprices of memory. In the manner of a kintsugi artist transforming a crack into an epiphany, she uses gold to fill and line her memories of journeys made and cul-de-sacs overcome. Amidst the smoke marks and kintsugi cracks on the map-shields, we recognise familiar signs: Bombay’s archipelago of seven islands and the grey concrete tiles paving its forever-under- construction roads. The clay that stains and covers the ridged lines carries its own cultural semiotics: an orangish hue alludes to Singapore; a deep red recalls the pots of Dharavi, a large informal settlement in Bombay that is home to a well-respected Kumbharwada, a potters’ colony.

As compared to the Singapore map-shields, the Bombay map-shields seem to have more detail and mimic the chaos of the populous city in their density. Might this happen because the artist no longer lives in Bombay, and therefore tries to recall the city with a haptic force she need not assert in her daily Singapore life? Or could it be that Madhvi’s private cartography of Singapore has instinctively picked up on the authoritarian impulses of what Cherian George calls the air-conditioned nation? In Singapore, where everything is in place and sanitised, the ratio of exposure to concealment is very different from a city like Bombay where the broken, the ungoverned and the ungovernable operate in plain sight.

What makes these map-shields such a tantalising Mnemosyne is the friction between the lyrical abstraction on their surfaces—the smoke marks, varying with their treatment, remind us strongly of soot-coloured Bombay walls or silken Rothko stains—and the sculptural objects themselves, which are anything but ephemeral or spectral. In fact, they have an air of being unbreakable, dreaming of immortality.

When the trees cast their soft shadows outside Madhvi’s studio in Singapore, the road looks like a perspective drawing. Only she knows that its desire to recede smoothly in space must remain unfulfilled. In a Rorschachian move, she twins the photograph of the incomplete road again and again, to retain the illusion of continuity.

When light falls on her earthen buildings, they cast the surprising shadows of trees. A sculpture becomes a dense sketch, an ephemeral wall drawing. A floor plan suffers from a genealogical quandary: Is it an excavated civilization, the aerial view of a metropolis, or a city slowly turning into an archaeological site unbeknownst to its greed-afflicted denizens? Elsewhere, Madhvi’s enigmatic shadow theatre—light gliding on a conveyor belt—turns generically constructed buildings into caricatures, distorted bodies swaying to a danse macabre. The stridulating cricket sounds in the background, which are made by the scraping of the insects’ wings, add to the dystopian atmospherics of the work (on sensing a threat to their habitat, male crickets are known to become extremely aggressive and make the most belligerent sounds). Hollowed out, evacuated of human presence, do these ruins of a post-industrial landscape embody her account of the ravages of the Anthropocene era?

Yet we humans must reclaim our redemptive agency. While exiting the gallery, we return to the artist’s foremost proposition. By contributing trees to the project, the viewers have renewed their sense of participation and belonging. And so, the artist has mapped a ground of trust, distributing the collective potentialities of affect and creative energy through the white cube.

The Clay-Wide-Web: An Unwritten History

“[Trees] are inextricably social beings. Under the ground, all trees are supported by symbiotic fungal partners. The tree supplies the fungus with sugars, the fungus attracts minerals from the soil and filters them into the trees’ roots. The complexity of this networking is only now being uncovered… The fungal network also acts as a conduit for sharing information about water availability and attacks by predatory insects, to the extent that it has been nicknamed ‘the wood-wide-web’.” Richard Mabey

The incredible chemical messaging system of the “wood-wide-web” has become a source of great inspiration and curiosity for Madhvi lately. On thinking about the specific dialect in which trees communicate with each other, I began to think of an analogous situation: How may we identify the various dialects of the art of ceramics in the Indian context?

Why is it that when, and if, on the rare occasion that we historicise contemporary Indian ceramic art, we invariably present a defensive position for it vis a vis the fine arts tradition, or make a cursory nod to the Arts and Crafts movement of the 1880s, which is only one of its many genealogies (moreover, this movement born in industrialised Britain was articulated through regional variations in America, India, Scandinavia and Japan)? Rather than shadow-boxing with the fine arts, we need to look at contemporary Indian ceramic art’s own rich and complex history of apprenticeship to more than one ceramic tradition, and the sculpting of its own transregional language.

On studying Madhvi’s pedagogical itinerary, I encountered a range of transcultural entanglements and affinities that have nourished her practice, and which deserve narration and analysis. As a college student in the early 1980s, she enrolled herself in a part-time pottery course at Bombay’s Sophia Polytechnic, even while studying Commerce and Economics at her parents’ behest. In the mid-1980s, at Golden Bridge Pottery (GBP) in Pondicherry, run by American ceramicists Deborah Smith and Ray Meeker, Madhvi learned to make wood-fired pottery by entering into the “skin of the material.” As a student there, she had to acquaint herself with the function of the raw materials—silica, feldspar, Ball clay, China clay—that constituted a clay body and the glaze. “I studied various clays from different parts of India for their colour and shrinkage individually, as well as tested them in a composed clay body.” Smith ran the production pottery wing at GBP and Madhvi admired her strict standards regarding weight, size and form. But the students were not expected to make work like GBP. While Meeker from whom she learnt functional pottery held them to those high standards, he also gave them the freedom to explore the endless possibilities of the art of ceramics.

After GBP, Madhvi wasn’t done with learning the craft. Like an Indian classical singer, she apprenticed herself to various gharanas of ceramic art, tuning into different temperatures of firing and glazing, boning up on rigour but also being entertained by the teacher’s idiosyncrasies; all the time imbibing a variety of ways to perceive the world through cognition and intuition. During a summer workshop at the Peters Valley School of Craft, New Jersey, in 1990, led by the American potter Warren MacKenzie, she continued to practice functional pottery and learned to perfect the Zen-like art of repetition, a way of overcoming the distractions of the conscious mind. MacKenzie’s approach was philosophical; his strength lay in “allowing yourself to see.” Madhvi reminisces how he anthropomorphized his pots by speaking of “the foot of the pot or the lip of the bowl.” She possesses three pots of this supremely accomplished mingei-sota potter—MacKenzie coined this deliciously hybrid term by mixing mingei, the Japanese folk art tradition founded on the belief that beauty lies in simple handmade objects and that aesthetics and functionality are not antithetical to each other, with “Minnesota”, the city where he built his kiln and taught at university.

At the Meadows School of the Arts in Texas, Madhvi received a holistic education in the arts, breaching the boundaries between fine arts and ceramics. She learned “the canons of a good pot’ from her teacher Peter Beasecker, who is known for his refined porcelain works. He never restricted her in any way, but a certain restlessness had crept into her practice. On the one hand, there was the expectation of a unique Indian sensibility in her work (the spectres of Orientalism cannot be chased away entirely). On the other hand, Madhvi was herself wrestling with the lack of the manifestation of “a unique me” in her work.

While at Meadows, her trip to New Mexico, where she attended a summer school, set her neurons firing again. The stunning desert landscape, the ancient adobe Pueblo Indian settlements, and the elegant grey and white Anasazi pottery, cast a spell on her. “It was as if New Mexico connected me to my own tradition.” Madhvi was trained in high-fired stoneware at GBP. However, her emergent interest in low firing, handbuilding techniques drew her like a magnet to Anasazi pottery. This experience strengthened her resolve to work with terracotta/earthenware and smoke firing—although terracotta is considered low down in the hierarchy of ceramic art as compared to say porcelain and stoneware.

As she extracts long-forgotten details from her memory bank, the holes in her ceramic sculptures begin to make new sense. The excavations of Anasazi mortuary rituals indicate that they would paint their pots with vibrant human, animal or geometric images and then “kill” them by making a hole with a sharp tool. They would put this pot with the “kill holes” on a dead person’s head so that her/his spirit would find a release. The holes in Madhvi’s pots, as I wrote earlier, help break the spell of formalist abstraction. But perhaps they do more than that: they promise freedom from the dogma of achieved protocols. If an artist wishes to practise an art form that retains much of its primordial force even in its contemporary avatar, something has to give for the air to circulate anew.

During their hikes into the mountains of New Mexico, Madhvi and her fellow students would often come upon Anasazi pottery shards lying around on hillocks. She has preserved a few fragments. We find other faraway traces in Madhvi’s works. Georgia O’Keefe had made New Mexico her home in her later years. The haptic deserts and mesas of Santa Fe and Taos make an appearance in O’Keefe’s paintings as tumescent skin folds, mortal and immortal all at once. As we pedal backwards into Madhvi’s works, we sense O’Keefe’s eroticism and humour coming through. Like O’Keefe, Madhvi has not fought shy of revealing erogenous zones in her work: we find an unabashed revelling in the linga and the yoni shapes camouflaged as anthills, pods, cones, flowers and arrows.

Madhvi’s self-education has taken her on a deltoid journey from GBP to American pedagogy, which is itself inflected with Japanese borrowings, and Native American erasures, and onwards to Dharavi and Manipur. We could place Madhvi’s encounters with hand-built Anasazi pottery alongside the work of potters in Dharavi who, as the artist puts it, “throw the pot with a hole at the bottom and then beat it to get the beautiful and ubiquitous round bottoms seen in matkas all over India.” Incidentally, Anasazi pots were made by women. Disappointed with traditional taboos against menstruating women touching the potter’s wheel in India, Madhvi was thrilled to come across the work of Manipuri women potters—who sidestep this restriction, shaping the pot with their hands with a wet rag while circling around it, in the process transforming themselves into the potter’s wheel.

I ask Madhvi about ceramicists Gurcharan Singh and Nirmala Patwardhan, who are not mentioned in her bio-data, but with whom she is likely to have crossed paths. As it happens, she is the proud owner of Singh’ gorgeous blue-glazed cups and has spent time at his Delhi Blue Art Pottery where he was endearingly addressed as “Daddyji”. A pioneer of studio pottery in India, he met Leach and Yanagi when he studied ceramics in Japan between 1919 and 1922. The Persian Blue glaze tiles have travelled along the Silk Route from Iran to Isfahan to Samarkhand, to Kabul and Peshawar, to India. This luminous glaze would have disappeared into history’s black hole had it not been for Singh’s timely intervention to revive it and give it a new lease of life at his Delhi Blue Art Pottery. Patwardhan, who grew up in Japan and had also worked with Leach in the UK, has left an incalculable legacy for ceramicists. Her systematic manual of glaze recipes, the Handbook for Potters (1984) is a first in the Indian context. Patwardhan often visited Madhvi’s studio, especially when she was firing her wood kiln. Madhvi remembers her as a “generous soul” who shared her knowledge and experiences readily.

Whether it was press moulding the skirting of the British ceramic artist Kate Malone’s installation, or making origami forms with very hard paper and using them as moulds at the American ceramicist William Daley’s retreat, Madhvi found herself sometimes overstimulated, and at other times emptied out, by each new experience (Daley would instruct his students: “Let the subconscious trickle in.”). But she never remained unprovoked.

It is a human tendency to charge forward into the future and leave behind that, which has become redundant; but it is equally true that we circle back to things we have rendered obsolete by our departures. While preparing for an installation that will be displayed at the Indian Heritage Centre Museum in Singapore, Madhvi feels like a student again. She has spent weeks making the same cup again and again, in a return to her GBP days, when she learned to make functional pottery. Only, this time, the reasons are not wholly aesthetic or functional, but political. She has literally found a measure to comment on the immeasurable horror of colonised populations forced into indentured labour. The trigger for this installation is a rubber-tapping cup that Madhvi found in the museum’s collection; such cups were made by the Chinese and used by the Indians on the British-owned plantations in colonial Malaya to collect the dripping latex from cuts made in the bark of the rubber tree. Madhvi’s installation consists of hundreds of such cups, all the same size but each distinctive in some way—chromatically, by way of pattern, and in the style of display. Each cup fixed to the wall might be identical—but isn’t. Just like the labourers, who were uniformly poor, but were individuals in their own right, dreaming their separate dreams.

Author

Nancy Adajania is a cultural theorist and curator based in Bombay. She is the editor of the transdisciplinary anthology ‘Some things that only art can do: A Lexicon of Affective Knowledge’ (Raza Foundation, 2017) and the author of The Thirteenth Place: Positionality as Critique in the Art of Navjot Altaf (The Guild Art Gallery, 2016). Adajania taught the curatorial practice course at the Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts (2013 and 2014). She is currently editing another anthology ‘Totems and Taboos: What can and cannot be done’ (Raza Foundation, 2018).

Nancy Adajania is a cultural theorist and curator based in Bombay. She is the editor of the transdisciplinary anthology ‘Some things that only art can do: A Lexicon of Affective Knowledge’ (Raza Foundation, 2017) and the author of The Thirteenth Place: Positionality as Critique in the Art of Navjot Altaf (The Guild Art Gallery, 2016). Adajania taught the curatorial practice course at the Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts (2013 and 2014). She is currently editing another anthology ‘Totems and Taboos: What can and cannot be done’ (Raza Foundation, 2018).