Tod Jones argues for the importance of craft produced today in heritage sites, particularly in contemporary communities who live with ancient centres in Indonesia.

Every piece of craft requires stories. Stories shape the movements of the people who make and maintain craft. The objects they produce bind people, place, memory, and materials and formalise socio-spatial relationships between people and places. In this way, objects are their stories. As a magazine that addresses “the stories behind what we make,” Garland can challenge the stories and structures that divide practices and determine value when this is required. As socio-spatial relationships shift, so must the stories that explain craft.

This story challenges postcolonial divisions between craft and artefact in Indonesia. It begins with a Javanese man called Sabar who was born in the village of Trowulan in the 1900s. In 1924 he began working with the Dutch architect and archaeologist Henri Maclaine Pont on his projects in eastern Java. This included excavating and collecting a large number of Majapahit artefacts and building a museum for them. When Maclaine-Pont was interred during the Japanese occupation of Java in 1942, Sabar moved his workshop to the grounds of the museum to care for the collection. He worked in an unwaged capacity at the museum, providing for his family through commissions until just before his retirement in 1965.

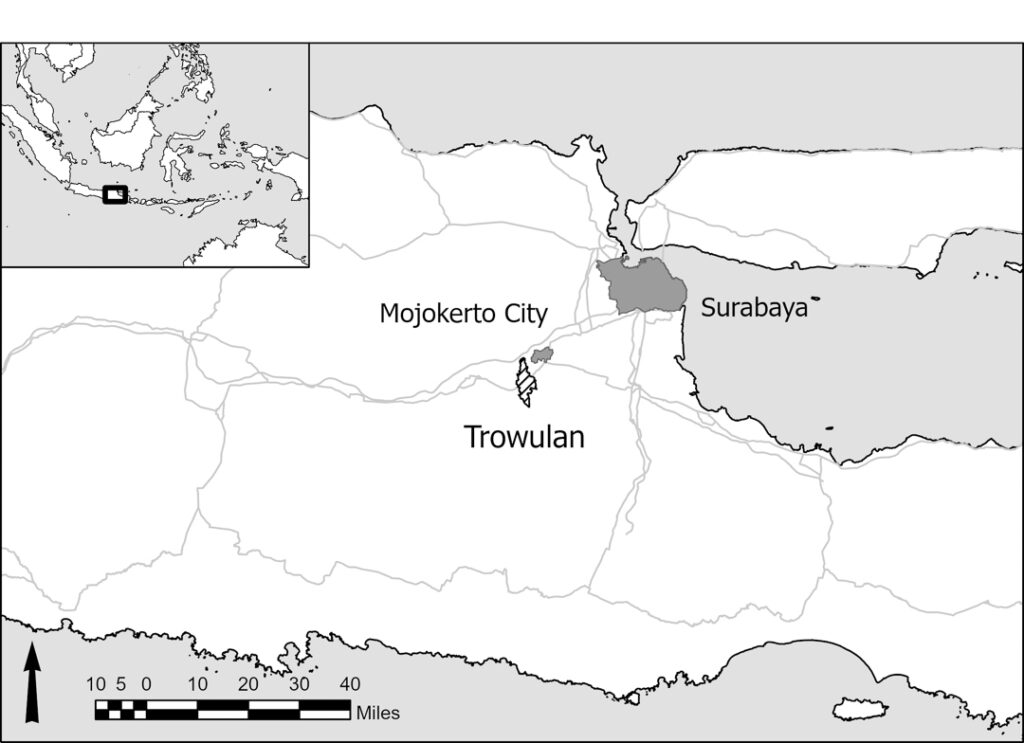

The Majapahit Kingdom, located in Trowulan, began in 1292 and exercised influence over an area close to the boundary of contemporary Indonesia in the fourteenth century before ending in c.1527. Majapahit is an important nationalist symbol of pre-colonial power and prestige, much like Rome is to Italians. Trowulan has long been of interest to archaeological research and heritage management since Sir Thomas Raffles undertook excavations in 1811-1816. It remains a focus of Indonesian and international heritage institutions. While the Majapahit Museum is still located in Trowulan, Majapahit artefacts are displayed in many international museums.

Sabar’s connection to the Majapahit continued after his retirement. He began to experiment with producing Majapahit statues using lead before progressing to metals and bronze. He sold statues in front of the museum and in Surabaya. He drew on his extensive knowledge to produce work following the style of the Majapahit with the goal of replicating their skill and design. While it is now difficult to locate his work, there is a self-portrait of the artist in the workshop of his son, Hariadi Sabar (see Figure 1). Sabar taught his family, friends and neighbours about manufacturing metal objects including large statues, generating jobs and businesses. Hariadi is the most well-known bronze artist in Trowulan and has worked in many national collaborations since the 1980s. According to Hariadi, over 150 people in Bejijong work in some capacity in the production of metal statues, jewellery and other objects. Sabar passed away in 1996.

Sabar is the initiator in Trowulan of what can be labelled Indonesia’s new classical arts. Now there are over 500 people employed in and around Trowulan in the artisanal production of metal, stone and terracotta craft. Craft production follows local Javanese conventions regarding training and copyright. The artistic peak remains to reproduce Majapahit style craft with the precision and skill of Majapahit artists. There are no formal copyrights although popular artists have shifted production inside compounds due to the speed at which their works have been copied. The important division in Trowulan is between higher-quality classical works drawing from Hindu and Buddhist traditions and quickly produced works sold at lower prices.

These artisanal industries are based on residents’ long-term relationships with Majapahit heritage, in particular local management of heritage, and the presence of the Majapahit museum. Artists often go to the Majapahit Museum and heritage sites for inspiration and guidance. Stonemason Ribut and Hariadi, two of the most celebrated artists, go to the museum weekly. Despite their reliance on the museum, the relationship between Trowulan artists and museums is tense. Trowulan artists can replicate and age objects with such skill that the museum struggles to determine their recent works from Majapahit-era artefacts and will ask senior artists to assist them in making determinations. This apprehension is perhaps even greater in international museums which are concerned about the providence of their collections.

The new Majapahit arts raises a number of questions about craft, power and postcolonial hierarchies within heritage management. While I view the creation of new Majapahit craft after a four-hundred-year gap as creative acts worth celebrating, museums view this with concern and the new objects as copies. As the division between old artefacts and new craft excludes Trowulan artists from heritage institutions and divides artefact and craft, it warrants further exploration.

The etymology of “artefact” comes from the Latin term arte factum, from ars meaning skill, and facere meaning to make. Both old and new craft are the product of “skilled making” and are linked through the attention and understanding of Trowulan artists. However, their continued shaping relies on very different relationships and stories. While museums use state funding and expert knowledge to establish regimes of care, cleaning, security and investigation for old craft at archaeological sites and in museums, Trowulan artists use national and international markets to employ community members to deliver and shape materials into new craft in their outdoor workshops. Both groups have strong emotional and affective connections with Majapahit craft and expert knowledge of Majapahit objects. Old and new Majapahit craft are artefacts that exist because of linked but separate stories that draw on and extend Majapahit craft practices.

The challenge that the new Majapahit craft presents to heritage institutions is to be open to the ways communities use colonial legacies to build livelihoods, hold knowledge and generate connections. The historical markers of Greater India that still dominate archaeology, through extensive local engagement and experimentation, are the basis for a skilled engagement that is entwined with place, family, livelihoods and history. Rather than dismissing this knowledge, the new Majapahit art, and the many instances of local engagement with artefacts and sites in other locations, should be viewed as opportunities for transformative collaboration. If we are not changed by a collaboration, there is a danger that it is based on a form of “inclusion” where we expect collaborators to restrict themselves to fit into our schemes and expectations. Common spaces are only possible if the stories they share change the people who come to the table, leading to new ways of approaching accepted concepts like artefact and heritage, creativity and creation.

This article draws from Tod’s recent book, Heritage is movement: heritage management and research in a diverse and plural world, published by Routledge.

About Tod Jones

Tod Jones is an Associate Professor in Geography at Curtin University in Perth, Australia. His interests and publications span craft, cultural policy, landscape and tourism in Indonesia and Australia. His most recent book, Heritage is movement: heritage management and research in a diverse and plural world was published by Routledge in 2024.

Tod Jones is an Associate Professor in Geography at Curtin University in Perth, Australia. His interests and publications span craft, cultural policy, landscape and tourism in Indonesia and Australia. His most recent book, Heritage is movement: heritage management and research in a diverse and plural world was published by Routledge in 2024.