Owen Rye recounts his ceramic adventures in Pakistan, with images of the pots that have lived with him in the 50 years since.

Owen Rye’s memoir Beyond Short Street recounts his adventures far and near. It includes his encounters with potters in conflict zones, such as Pakistan and Palestine, as well as the local turmoil over art education in Gippsland.

To accompany the words, Owen Rye still has pots that he collected during his travels. These passages from his chapter on Pakistan are illustrated with the objects that are now part of his everyday life.

✿

In the beginning chaos, and in the end Chaos; and the vast wonder come between.

Conrad Aiken in Preludes

Everyone has a best year of their life, and a worst year. As the good year, 1971 is my contender; the year of my first grand adventure. What is offered here is just a small slice of one large year — and its follow-up a few years later (1977). Taken together they amounted to 12 months travelling the length and width of Pakistan from Karachi to Hunza, from Bannu to Lahore. Those travels could fill a book in themselves — in fact they did. My book Traditional Pottery Techniques of Pakistan was published by the Smithsonian in 1973.

The Pakistan experience was my first time out of Australia; coincidentally when many Australians were having their first world travel experiences. Air travel was just beginning to be open to anyone because of better aircraft and lower prices.

Pakistan was a different country in the 1970s than it is now. The northern part of the country was exotic enough that there are many books written about it, including Eric Newby’s A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. There was danger in some areas where I travelled. Understanding the intricacies of local culture was essential in risky areas of the North West Frontier, and knowing how to behave as a local helped create some safety. Even in the most dangerous areas, the when-in-Rome wisdom applied. Not carrying anything worth stealing removed the risk of being robbed. Not behaving in ways that were forbidden to locals helped the process of fitting in.

Now the situation is more extreme. Some areas have been opened up to tourism and may be safer. Elsewhere political developments have created a new level of unpredictability. Extreme Islamists attack unwary foreigners in remote areas. Although I would love to revisit some areas caution prevents me; living seems a better option.

✿

Multan

My work soon became routine. Working with an interpreter, I made enough time with each potter to discover how they worked, and photograph them at work, and their surroundings. Their main piece of equipment was usually a simple potter’s wheel, built into a pit in the ground. The most common types of pottery were unglazed red earthenware water pots, and cooking pots. Kilns were simple, made of stone or clay, rarely brick. They were fired with grass, straw, wood or cow-dung for fuel. Potters were poor, earning a few dollars a week. A large water pot sixty centimetres (two feet) tall might sell for a few cents and take up to two hours to make.

This varied. Potters in Multan and Hala, in the south of Pakistan, made more sophisticated glazed and decorated ware, and the methods they used were far more complicated.

✿

Multan is one of the world’s oldest cities, beginning during the Indus Valley civilisation some four or five thousand years ago. The complex tangle of ancient streets makes Multan one of the most difficult places to navigate I have ever encountered. In summer, it is a viciously hot dry place, surrounded by desert. My interest in Multan involved kashi, the Multan Blue pottery, one of the best-known pottery styles in Pakistan, available through shops in many centres. The most prominent use of the blue pottery is in tiles. These can be seen on many beautiful mosques and tombs around the city and elsewhere in Pakistan. Especially in the drier areas of the country the blue and turquoise decorated tiles stand out in stunning contrast to the dry dull brown desert colours.

Multan kashi has a white slip and clear glaze, with cobalt blue and turquoise copper coloured decoration. This ware is based on ancient technologies going back to the origins of glassmaking in Mesopotamia. This early glass was made by combining ash from burning salt bushes that grow in the desert, with silica from various sources. When heated until it melts, it becomes glass. Some Islamic alkaline glazes were also made from similar mixtures. Multan pottery allowed me to study this most ancient ceramic technology. Because of their significance in the history of technology of both glass and ceramic glazes I needed to go out into the desert and collect samples of these plants for analysis later, in Washington.

✿

I took the Wagoneer into the Cholistan Desert, travelling with Azizullah Khan Khalil and a local guide. From Bahawalpur, we headed south-east towards the Indian border around 100 kilometres away. I planned to collect samples of the type of desert saltbush burned by the Multan potters to make ash they used in glazes.

The daily top temperature varied from around 38°C (100°F) in the cold parts of the plains to around 50°C (120°F) in the desert. The average temperature in the Cholistan desert at the height of summer is around 55°, average indicating that the temperature is often higher. This is the real desert of myth, an empty desert, with sand and more sand, sometimes raised into gently rolling dunes rather than massively steep ones. With low tyre pressures to prevent sinking into the sand, the Wagoneer did the trip with no dramas. Had we been forced to stop nobody would pass by; the chance that a nomad might appear on a camel was non-existent. We had no radio or other means of communication. We were totally reliant on the Wagoneer.

I had seen nomads in the harsh Waziristan desert, dressed in loose flowing clothes, covered entirely from head to foot, with only their eyes showing. The reason they dressed that way soon became obvious. As we moved further into the Cholistan the temperature rose to the point where any air movement past skin caused blisters to develop; the skin was literally being slow-cooked, beginning to bubble. Driving with all the windows closed, the temperature in the vehicle, which was not air-conditioned, was almost unbearable. After an hour, perhaps an hour and a half, we found some plants that looked like they might be the ones, low saltbush. I took some time collecting samples, bagging and labelling them.

- Sher Zaman

- Sher Zaman

While I was doing that, I heard a piercing shriek from the east, unlike anything I had ever heard before. Something was approaching, moving extremely fast. Then in the sand maybe a kilometre away there was an eruption of sand into the air accompanied by a loud explosion. It took a while to work out it had been an artillery shell. Then another came, maybe 100 metres closer. Followed by more, one each minute or so, each a hundred metres closer again. My ability with arithmetic has always been a bit rough but a quick calculation told me that we had about seven minutes to get the hell out of there — or have an artillery shell explode right on top of us. We were well away by the time seven minutes had elapsed. The Indian artillery-wallahs on the other side of the border were having a bit of a practice run for the war that was coming with Pakistan. Poor old Khalil was probably silently wishing he had never seen us mad Westerners.

That same saltbush gave me more trouble later in Israel. Travelling along a road in the Jordan Valley mostly used by Israeli military vehicles I saw some similar saltbush in the near distance, maybe fifty metres off the roadside. I stopped and walked over to collect some samples. While I was pulling up some bushes an Israeli military jeep stopped and the driver yelled something at me. I ignored him for a while. I was never in a mood to respond to Israelis yelling at me. He then tried English and the word ‘mines’ was very distinct. I was in the middle of a minefield. I am not using the cliché expression often used to describe a difficult situation. I was in an actual minefield; where things blow up when you walk on them and you become dead or maimed. I have never so carefully trod in my previous footsteps, to get out of there. There were actually signs in Hebrew, Arabic and English along the roadside warning about mines when I looked later. I had stopped in between without registering them.

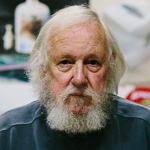

About Owen Rye

I have been making and exhibiting ceramics for sixty years now. My studio and home are at Boolarra South, in the Gippsland hills. I also write – have now published five books, and in ceramics magazines worldwide more than 100 articles. Also interested in photography and working towards an exhibition in June 2022.

I have been making and exhibiting ceramics for sixty years now. My studio and home are at Boolarra South, in the Gippsland hills. I also write – have now published five books, and in ceramics magazines worldwide more than 100 articles. Also interested in photography and working towards an exhibition in June 2022.

Comments

Hi Owen, great to read of your adventures in Parkistan. Triggered my own memories of the extremes experienced during a month long AIR in the Ceramic Design Studio at their peak National College of Arts (NCA) in 2006. (Catalogue and Pyre article on my website). I was invite and declined a visit a popular Lahore mosque on my last day, later that day it was bombed (no link!). Still have fond memories of and ocassionally have contact with the staff, artists and students I came to know. Still play the great uptempo music they burned onto a CD as parting gift. Used to play in the lab where I did all my emailing each day…