Gary Wornell is impressed by the creativity, skill and commitment to Nepalese culture by the new generation of street artists.

It’s more than a decade now since I first landed in Nepal for the Kathmandu International Arts Festival and nearly a decade since I have spent the greater part of my year living and working here. Before coming I had reached out to various arts organisations in the city offering photography workshops as a way of meeting young creatives in a country that I only knew by its incredible Himalayas and the predominant spiritual practices of Hinduism and Buddhism. From the list of contacts I had, one young artist, Kailash K. Shrestha, stood out as a dynamic force and committed practitioner and educator, and in late November of 2012, I got up at 5:00 am to travel across town to begin my series of workshops to a packed classroom at 6:30 in the morning in his studio. I wasn’t prepared for the eagerness that awaited me and the enthusiasm of the participants. I’m reminded of those days each time I take my morning coffee before sunrise on my terrace opposite a college where students are drifting into the schoolyard at 5:30 am. These young hopefuls are early birds in their black uniforms vibrant with energy.

Kailash K. Shrestha stands in front of “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity” 2022. The text is the first few lines from the Nepali National anthem.

Kailash, I soon realised, exhibited a strong independent and catholic approach to the arts. I remember one of our first conversations where he expressed his view that the art scene in Nepal follows two distinct paths: the traditional paintings that adorn the doorways and walls of temples including the Buddhist thangkas that have been meticulously copied over hundreds of years (for which he expressed a deep respect and love), and secondly, the more formal Western-influenced “gallery” exhibited arts which for the most part ignore the ethnic origins of the artists, precluding engagement from a general public, and attempting to reflect something contemporary in a country struggling to provide adequate health and education services, infrastructure and political stability for its citizens. Kailash felt at the time that the formal setting of a gallery was so alien to most Nepalis busy with their everyday struggles that there was a golden opportunity to bring contemporary issues into the public domain. It lay firmly on the walls of the city—the walls that people pass daily. This was a natural place for creative expression, comment, political and social discourse.

My experiences with marks on walls in the developed countries where I have lived for the greater portion of my life are informed by the graffiti sprayed hastily on grubby underpasses in urban settings or on the sides of public buildings with a scale determined by arm’s length arches of stylised letters whose sole purpose could be summarised to say “Here I am – I exist”. The desire to make marks in challenging socioeconomic circumstances is deeply rooted in our psyche but it was the work of the renowned British artist Banksy that brought, at least for me, a sea change in the way I thought about street art and the power to influence public opinion and affect change.

When Kailash first talked about his passion to promote wall art in Nepal, I struggled to see how this would materialise in a city so cluttered and dirty as Kathmandu. Helsinki, yes: plenty of architecture as pristine as a gessoed canvas just waiting; Montreal, yes; London, sure. But Kathmandu seemed to me to present huge challenges. Not only those of appropriate locations in a visually cluttered metropolis, but the daring freedom of expression on sensitive subjects in a fledgling democracy could present significant risks to anyone publicly challenging the status quo.

Nepal is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world. It has over 120 distinct languages and an equal number of dialects, each with its own customs, traditions, and family values spread over the rolling hills of the Himalayas and down into the flat plains of the Terai. Each of these ethnic groups has its own distinct art forms; some are more easily recognised than others like the Mithila arts of Janakpur or the religious works of the Newar as well as those of the Sherpa’s, Tharu’s and Abadhi’s. Acutely aware of the importance of validating and encouraging these indigenous groups to expand their audiences and promote free expression, Kailash determined to engage selected communities across Nepal in expanding their repertoire normally confined to private interiors, to bring them into public spaces, breathing life into otherwise bland locations and dive into the important issues that affect their lives, opening up public discussion at the same time enhancing the urban landscape. Keeping in mind that although Nepal became a democracy of sorts in 1951, it wasn’t until the monarchy collapsed in 1990 that creatives in all disciplines had the opportunity for free expression since before that, the King had absolute power.

Once the gate of the paddock was opened, it took decades before anyone felt confident enough to venture into the unknown. Most wouldn’t even consider wall art something one could do, and Kailash set out to curate several pilot projects to test the waters. It is hard for us in the West to imagine only thirty years of freedom of creative expression; something those of us lucky enough to live in democracies take completely for granted. Considering the ten years of civil war that the country faced from 1996 to 2006, that number is more like twenty. Nothing.

Contemporary Nepali art struggles to find support from government and municipal authorities when other more pressing development issues demand attention. Traditional, religious and secular art are grouped together in a privately funded Museum of Nepali Art, but there is no state-funded collection available to the general public and tourists to the country are faced with the limited choices of MoNA or privately run commercial galleries relying on sales which attenuate the expression to what can sell. Thus, the opportunity for young artists lies mainly on the landscape of the city walls where provocative social statements promote awareness and initiate discussion of important issues on the subjects of social inequality, health, domestic violence, rape and political unrest to name just a few.

Nepali street art seems to have taken leaps and bounds into the public arena since around 2010. Kailash K. Shrestha’s vision to bring graffiti artists and mural painters together has led to a series of high-profile works over the last decade on the boundary walls of schools and colleges, hotels and commercial buildings and a few government institutions. Notably his initiative of 2011 “We Make the Nation” marking the Democracy Wall in Bagbazar, Kathmandu on “International Youth Day” departed from the traditional messages promoted by the numerous political parties to a non-partisan reflection on the “essence of democracy” as Nepal struggled to find unity across the socio-economic divide. Since then Kailash has curated a number of inspiring community-based street art projects throughout the country including “Breaking the Silence – Art Against Women Violence”; “I’m You – Questioning Identity and Socio-political Realities” and most recently “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity – 2022”, engaging a wide range of ethnic minorities and promoting and encouraging visual artists to use the urban landscape as a canvas for the issues to be aired.

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Kailash K. Shrestha in front of the Mithila section of “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity”. Artist Manisha Shah, Sunsari, Nepal

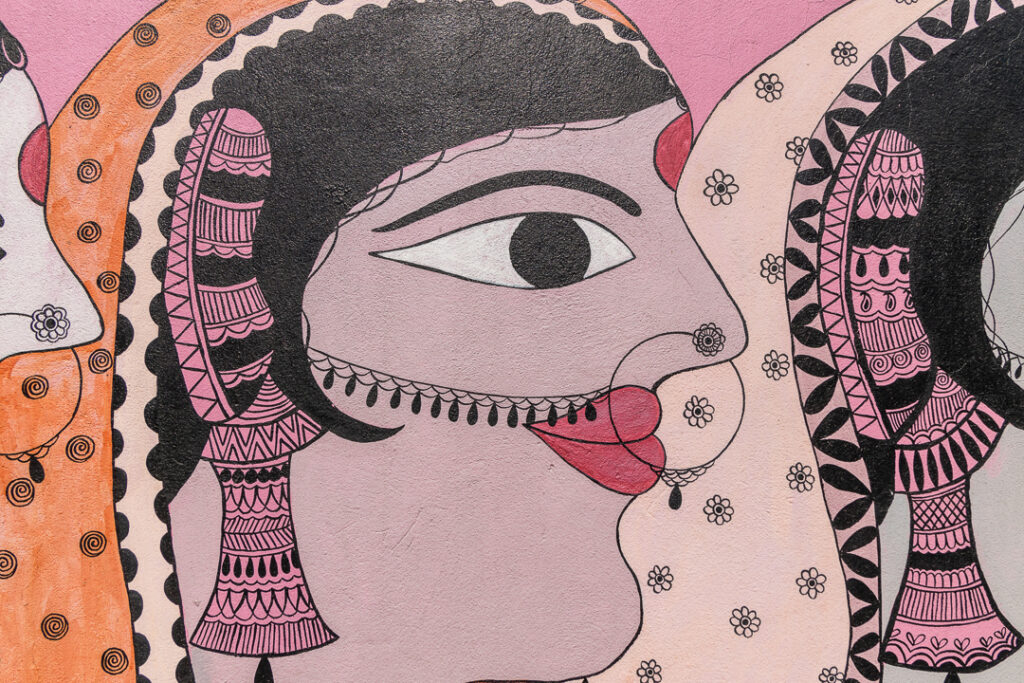

- Detail of the Mithila section of “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity”.

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Section of ‘Ekataka Bhitta: The Wall of Unity’

- Detail of “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity” with the artwork of Tsering Phonjo Gurung, Mustang, Nepal.

- Detail of “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity” Artist Bishal Manadhar, Bhaktapur, Nepal

- Detail of the “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity” Artist Kiran Maharjan, Lalitpur, Nepal

A few days ago I met up with Kailash and we drove out to see “Ekatako Bhitta: The Wall of Unity”. I was surprised how well it had weathered in the two years since its completion given the high humidity during monsoon and the intense UV from sunlight. Most wall artworks in Nepal have limited lifespans suffering from crumbling surfaces and fungal growth. Our conversation focused on the cultural diversity of the artists brought together for this project; artists from the far west in Mustang to the far east in Janakpur; and the cohesive way in which it had all come together: the celebration of a unified nation. The Wall of Unity symbolises the potential of ethnic minorities to express themselves through their unique perspectives and bridge the gaps that have divided the country for centuries.

Ratification of Nepal’s constitution in 2015 made the inequalities of the caste system illegal, but the prejudices inherent in the social hierarchy, work and education are deeply embedded in the culture and remain even to this day. Artudio has sought to address social caste-based inequality by engaging minority groups in the east of the country, like the women of Janakpur, in collaboration with international guest artists, to express themselves through their traditional art form of Mithila and create street artworks on contemporary themes that delve deeper into the issues that reflect their place in today’s world.

The growing presence of street art projects whether they be curated by Kailash K. Shrestha’s Artudio or the numerous independent creators who have been inspired by his initiatives are playing an increasingly vital role in raising awareness and initiating discussions around important subjects including child protection, women’s health, corruption and labour exploitation, to name but a few.

- Festivity Mural. This work is chariot influenced by Rato Macchendrath – an annual festival in Patan, Nepal. Designed by Vijaya Maharjan and painted with the help of Sudeep Balla situated at Labim Mall, Lalitpur, Kathmandu

- Festivity Mural. Detail of the work by Vijaya Maharjan and painted with the help of Sudeep Balla situated at Labim Mall, Lalitpur, Kathmandu

- Night view of the pop-up mural at Gangasagar, Janakpur, Nepal

Street art in Kathmandu has brought into the public eye the young creative talent in the city. From the early forms of graffiti of a decade ago, the change that is taking place is inspiring. The result of initiatives instigated by the art community has not only brought forth a shift in attitudes, but has also induced the commissioning of murals from a wide range of corporate patrons including restaurants, malls, educational establishments and private individuals. Nepal is entering a new era of artistic expression in the public domain, embracing the past and looking to the future. The city that I first came to all those years ago, struggling to embrace new technologies and build efficient infrastructure is rapidly changing. Improvements in essential services, roads, electricity and water supply have made a significant impact on the urban landscape and the acceptance of street art as an important part of that landscape is contributing to the story.

I recently went across town to Patan on the south side of the river. On the outskirts of the ancient kingdom is a modern mall; clean, elegant and inviting and not unlike something one would find in any highly developed country, but the thing that caught my eye was a work towering above me on the side of the building by a Nepali artist, Vijaya Maharjan and painted with the help of street artist, Sudeep Balla, a bold and vibrant mural fusing traditional elements in a contemporary style celebrating Nepal’s unique cultural heritage and reflecting the positive energy of a young demographic who started their careers with spray cans and brushes a decade ago on the back streets of the city.