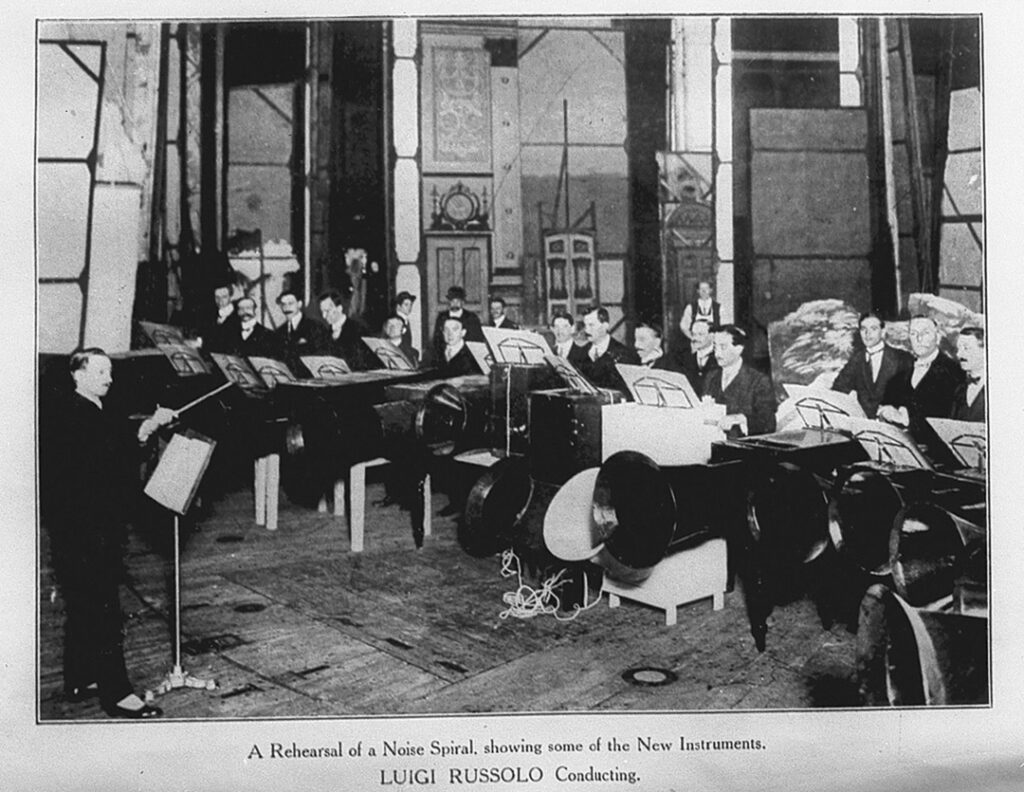

Luigi Russolo conducting a rehearsal of his Intonarumori orchestra, London, UK. c1914. From a donated scrapbook. No accreditation. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, USA.

Gary Warner explains why we should listen more carefully to what we think of as “noise” in order to connect more closely with the world around us.

Italian futurist artist Luigi Russolo was among the first to design and build noise machines to acknowledge and emulate new, modern sounds of machines and industry—sounds of speed, power, transport, and mass production.

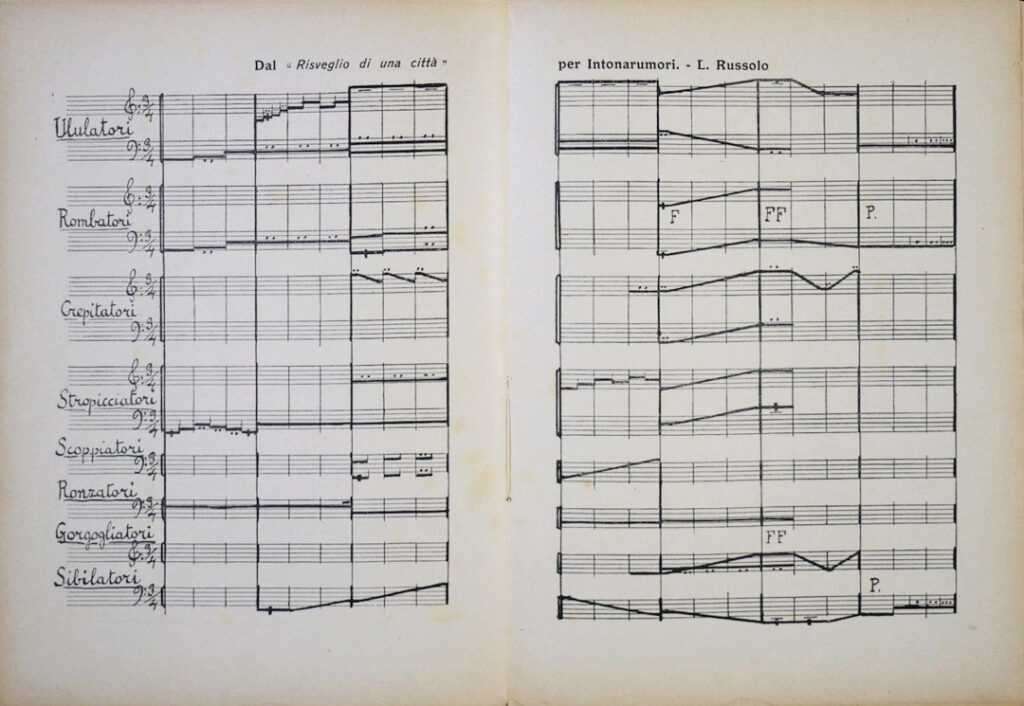

His Intonarumori—noise tuners—were analogue experimental sonic sculptures resembling modified packing cases and didn’t look or sound like any conventional musical instrument. Hand cranks and levers were used to vary tension and contact with vibrating strings attached to membranes hidden inside the large boxes. Their sounds were amplified through large conical horns attached to the front. Russolo devised a new way of scoring for his instruments, an early example of the graphic notation that would flourish in the avant-garde through the twentieth century.

Luigi Russolo, score for Risveglio di una città (Awakening of a city) for eight Intonarumori – Ululatori (howlers), Rombatori (gritty howler), Crepitatori (crackler), Stropicciatori (scraper), Scoppiatori (combuster), Ronatore (buzzer), Gorgogliatore (gurgler), Sibilatore (whistler). Published in L’arte dei Rumori, 1916.

Most of Russolo’s original creations were destroyed during World War Two or lost. In the twenty-first century, some experimental musicians and artists collaborated with luthiers, technicians and instrument makers to interpret and recreate the Intonarumori. Concerts were staged in 2013 to celebrate the simultaneous centenaries of Russolo’s manifesto “The Art of Noises” and the birth of John Cage, an avant-garde composer and another advocate for reconsidering the qualitative distinction we make between music and noise.

There is a significant distinction, though, between Russolo and Cage. The former, along with other artists of the Italian Futurist movement, was tangled up with the rise of Fascism and ideas that discord, the violence of new noise, mirrored a necessary violence of warfare that would purify a world grown stale through tradition. Conversely, Cage, inspired by his exposure to Japanese Zen, asked us to consider the beauty and pleasures to be found by being open to sounds as we encounter them.

Cage came to believe that “noise” is a term we use to differentiate sounds we want to avoid, exclude and silence. Noise is disruptive, subordinate, and unruly; the term is prejudicial and hierarchical. For Cage, music is nothing more than a separating categorisation for noise we choose to elevate to the status of valued cultural production.

John Cage studied composition with Arnold Schoenberg in the 1930s in Los Angeles. In 1942 Cage wrote that the music of the future would contain many kinds of sounds, so from a compositional perspective, a string of sounds, a melody, could contain any sounds regardless of their contrasts. And he proceeded through his long career as a musical explorer and experimentalist to performatively express this tenet.

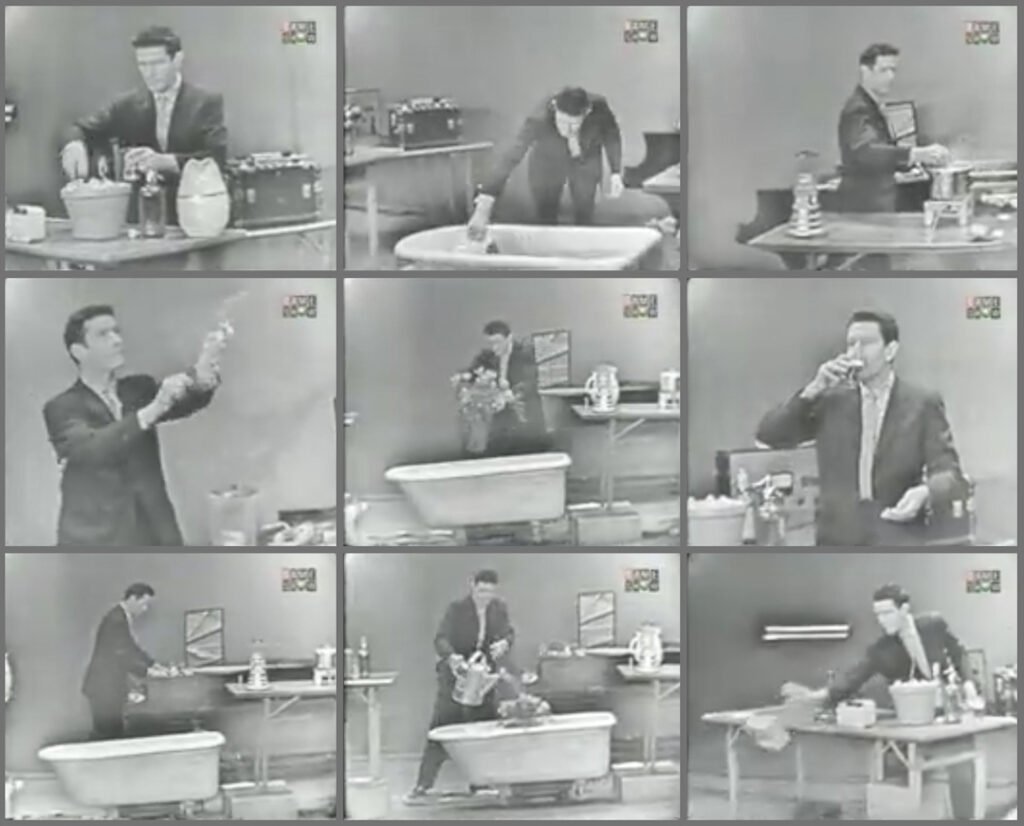

John Cage performing Water Walk for Solo Television Performer, New York TV, 1960. Still frames from archived video – link below.

A fine example is his 1959 “Water Walk”, composed and first performed in Italy on television. It utilised 34 different objects and materials, and a low-speed tape player. Lasting only a few minutes, its sounds included water pours, splashing, a soda fountain, mechanical toys placed in an open grand piano, a pop gun, a steam pressure cooker, thumping and dropping various objects, bird whistles and duck calls—all presented in scored sequence by the fast-moving well rehearsed besuited avant-gardist who constantly references a stopwatch.

Percussionist Katelyn Rose King performing John Cage’s Water Walk. 2016. Still frame for YouTube video – link below.

Naturally enough, the live audiences for the first performances—in Italy and New York, also on TV—experienced it as entertainment and laughed heartily throughout. How else could they respond at that moment, in that context? Recent performances of the now canonical work typically play out in hushed reverence. The composition hasn’t changed; its cultural place has, our considerations of noise as music have. But there’s still room for humour in response, which Cage would have appreciated, I suspect. A comment on a 2016 YouTube video of ‘Water Walk’ performed by Katelyn King reads, “I’ll be humming this one all day.”

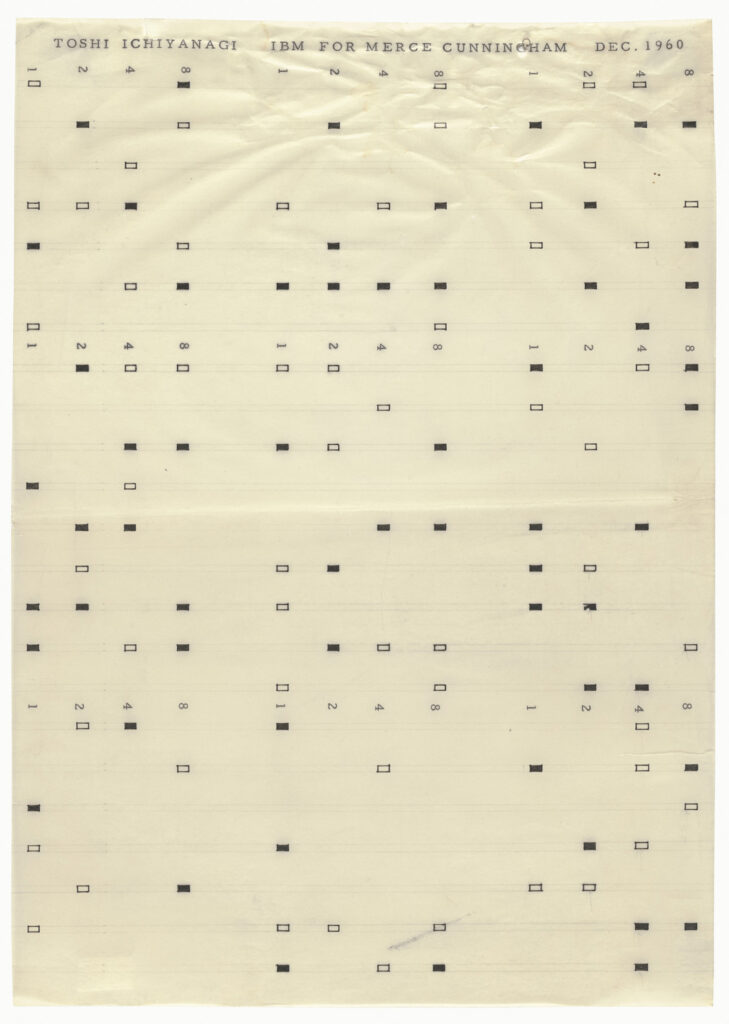

Toshi Ichiyanagi. IBM for Merce Cunningham. 1960. Ink, typewriting, and pencil on paper, 21 x 29.3 cm. MOMA, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift. Object number 2259.2008

In the early 1960s, Japanese experimental composer Toshi Ichiyanagi, a student of Cage while living in New York, prepared a visual score for performative interpretation with sound and movement. Titled “IBM for Merce Cunningham”, the piece is based on the binary language of punch-cards used to mechanically “write” computer code then. This technology was a direct descendant of a device invented by Frenchman Joseph Marie Jacquard and first demonstrated in 1801.

The Jacquard mechanism was attached to a conventional loom to provide a precoded binary instruction for weaving complex patterns via dozens of large, carefully prepared hole-punched cards. A skilled weaver operated the loom—this was not yet complete automation—and we can imagine the rhythmic clatter, whoosh and slap of its use. Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, in the mid-nineteenth century, developed Jacquard’s ideas into the antecedents of every modern computer—Babbage with his proposed Analytical Engine and Lovelace expounding the first computer algorithm. In 1842, she speculated about the machinic future we now inhabit, writing:

“Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, [the Analytical Engine] might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.”

That prescient imagining has, of course, been realised. Anyone with access to digital devices can prepare music and soundscapes made of any imaginable and infinite unimaginable sounds without necessarily possessing any knowledge of musical tradition.

This democratised access to the means of production of audiovisual media has led to some interesting developments in the explorations of noise and making. The notion that digital users have been forced into an attention economy that favours brevity is a kind of environmental pressure requiring adaptation. Viewers no longer sit in theatres or even in their homes to dutifully consume time-based media. The delivery screen is carried in the pockets of millions, watched and listened to on public transport, in lecture halls, waiting rooms, forest getaways, workshops, workplaces, parks and gardens. The choice of media to consume is as good as infinite. So much to see, so little time.

A newish genre of digital output by craft makers is the micro-movie documentary, a rapid-fire sequence of brief scenes capturing a journey from raw material to finished object.

A newish genre of digital output by craft makers is the micro-movie documentary, a rapid-fire sequence of brief scenes capturing a journey from raw material to finished object. A series of processes that may have taken days, weeks or months is collapsed into a minute or two of media designed to arrest that most elusive and volatile of properties, human attention.

Most of these productions underlay their scenes with a cohering gel of popular songs. Personally, I find this methodology of little interest. What holds my attention are pieces where the actual sounds created by each process—the diegetic sounds—are captured to accompany their visual referent. Each brief scene offers its characteristic sound/noise; together, they become a unique composition, a music of making that fully realises Cage’s 1942 proposal about a future form of music.

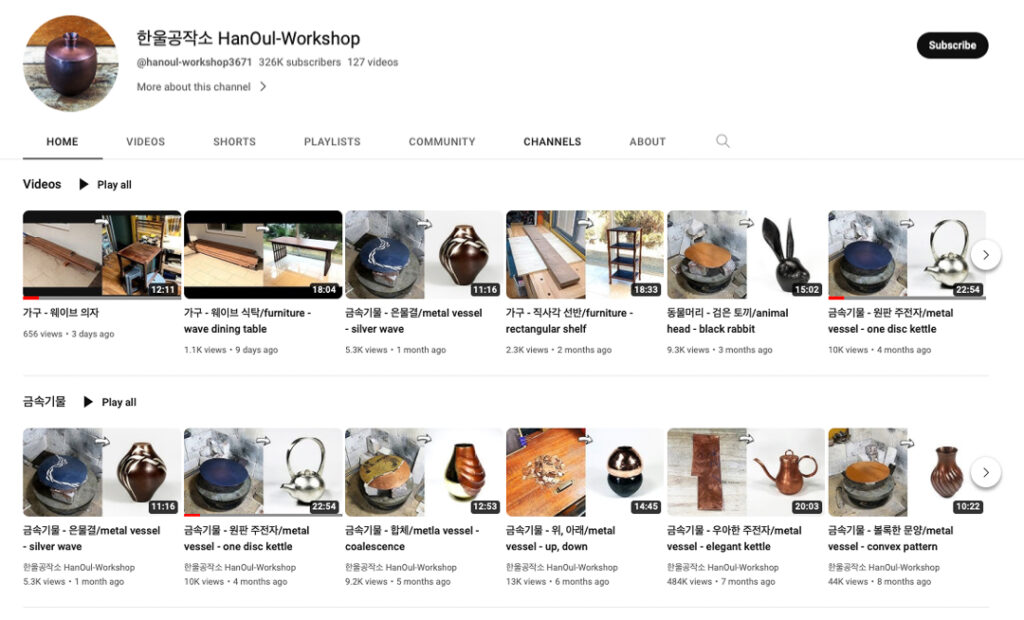

The best example of this genre I know of is the YouTube video channel of HanOul Workshop, a Korean maker or perhaps a group of makers who make extraordinary videos documenting every stage of skillfully making beautifully crafted objects in woods and metals. For example, “metal vessel – one disc kettle” begins with a rectangle of copper being dropped on a bench and ends 20 minutes later with a water pour test of the exquisite kettle the sheet has been transformed into. Not a word is spoken throughout; the entire soundtrack comprises the sounds of making.

Drawing, ruling, cutting with tinsnips and hacksaws, rhythmic working with various metal hammers and wooden mallets, hand and machine filing, annealing, wax melting and filling, smithing over anvils, smelting, drilling, heating with torches, plunge cooling, chemical bath processing, water cleaning, testing – each of these videos is a completely fascinating catalogue of noises, a unique sonic chronicle of making.

Further Listening and Viewing

INTONARUMORI 100 :: watsON? NOISE 2013

Luigi Russolo, Intonarumoris, 1913. Lisboa, Museu Coleção Berardo, 2012.

Katelyn King performs Water Walk by John Cage, 2016

Andrea Neumann performs “Water Walk” by John Cage, 2012

Score for Water Walk, John Cage. 1959.

Shuta Hasunuma Philharmonic Orchestra perform Toshi Ichiyanagi’s “IBM”, Sogetsu Hall, Tokyo. 2018

HanOul-Workshop – metal vessel – one disc kettle

HanOul-Workshop – walnut chair

Comments

It’s exciting to watch how the copper plate turns into a beautiful treasure chest for brewing tea in dexterous hands. The video and sounds are great… and this tiny teapot is a visual to watch for hours