Sally Simpson, Venerated Remains, 2012, lace,fish bones and scales, mud, gold leaf on mirrored, aluminium base, photo: David Paterson

The young Maori woman haranguing us from the podium had a tattooed chin and a story to tell, of a sacred object belonging to her ancestors that had found its way into a museum. She held us spellbound for fifteen minutes past her allotted time, giving us a view from the perspective of the collected rather than the collector, and stepped down, magnificent and unapologetic, to accolades and applause. The event was a Museums Australasia conference in Auckland about the relevance and future role of museums, and one of the most significant issues to emerge from the keynote speakers and panel discussions was the challenge museums face over their ethnographic collections—all those tribal artefacts and human remains, the masks and shields and spooky fetish objects gathered by scientists and explorers and adventurers. The descendants of the people to whom the artefacts and skulls belonged are demanding a say in how the collections are displayed and interpreted, and in some cases the return of certain objects, especially the human remains.

Subscribers also read this as an epub or pdf.

The historical contexts and the motives of the collectors are in the frame for questioning. Time has wrought a dramatic change on the meanings we attribute to the museum display and the interpretations attributed to the collections. The “exotic” and the “primitive” are stepping out of their display cases, emerging from their labelled shelves and drawers in the museum store-rooms, re-asserting their power and re-defining their meaning in the world.

One of the most thought-provoking ideas I took from the conference was the way in which contemporary indigenous people respond to museum collections with discomfort and anger, while many of us who belong to the non-indigenous baby boomer generation remember the sense of awe and magic those collections instilled in us.

Another significant strand was the question of how museums should address climate change and the environmental fallout that will accompany it. There was a consensus that museums must retain their capacity to ignite a sense of wonder, and in so doing make us care about where we have come from and where we might go. What a museum of the future might look like was subjected to the question of how far into the future. A hundred years? A thousand years? Ten thousand years?

To which I would add the question—what sort of objects will continue to speak to people in a thousand or ten thousand years? What artefacts will transmit meaning about the times we live in and the concerns that preoccupy us? If an object from ten thousand or a thousand years ago continues to speak to us now, then chances are those same qualities will communicate into the future.

It is with this in mind that I will talk about a work by the sculptor Sally Simpson, a long-time friend whose practice I have watched evolve over the past thirty years, whose work questions where humans fit in the land, and what values they assign to it. She makes objects for putative inclusion in an unknown future museum, a place where she imagines that the wonder is maintained, where the objects carry ambiguous meanings and stir visceral responses. Always disposed to make work that focuses on her daily environment, moving from the city to a small farm focused Sally’s interests on making sense of what was happening around her, to the land and the people who lived on it.

The work I’ve chosen to focus on, Venerated Remains, encapsulates a moment when a particular place is in a state of transition. It reflects the attempts of a settler Australian to tease out her relationship to the land in a way that attributes universal themes and meanings to a specific place.

Sally Simpson, Venerated Remains, 2012, lace,fish bones and scales, mud, gold leaf on mirrored, aluminium base, photo: David Paterson

In 2009 Sally Simpson was among a group of artists from the Australian National University, who visited a decommissioned artificial lake in north-eastern Victoria as part of a field studies program about art and the environment. By this time, the drying lake bed had become an archaeological site, revealing the detritus of forty years. In the four decades between its inception in 1971 and its decommissioning in 2012, Lake Mokoan was subject to extreme evaporation and regular invasions of toxic algal bloom. Too shallow to provide reliable water for irrigation of the surrounding farmlands, it nevertheless became a popular recreational site. Among the skeletal remains of Golden perch, Murray cod and European carp were fishing lines and fish hooks, shotgun shells and Coke cans, irrigation pipe and fencing wire. The piéce de resistance was a mud-encrusted lace tablecloth, remnant of some decorous Sunday picnic or domestic crime scene.

Sally says of her first encounter with the site, “I found it visually spectacular, a vast expanse of anaerobic mud punctuated by the stark black shapes of dead redgums. Benalla council was undertaking work to revitalise it. This was a perfect opportunity to engage with land knowing that its current state was about to be changed.”

An aerial photograph of Lake Mokoan taken in 2008 shows a body of water that looks like a bleeding heart. The Winton Swamp was never meant to be a lake. It was one of those places where humans decided to improve on nature, diverting water from two nearby creeks into the swamplands to create a permanent body of water. Ephemeral lakes are a feature of the Australian landscape, but this artificial lake in the throes of bleeding out was made more poignant by the evidence of what it had cost to create it—the dead trees, drowned when the water from nearby creeks was diverted into the swamps—the dead fish, suffocating when the lake was drained. These things occur as part of the natural cycle, and are reminders of the vicissitudes of nature. But when they are brought about by human interventions they become an object lesson in the risks we take when we mess about with nature.

Cutting off the water source to the lake has caused considerable grief to the people who had become accustomed to it as part of their physical world. But neither can the place be returned to its original state. Too much has changed in forty years, and the site is on the way to becoming a managed wetland, subject to regulations and restrictions, among them a ban on flying kites and throwing stones.

But in 2009 it was neither one thing nor the other, and there were no restrictions on access or collecting materials. It was this state of in-betweenness that spoke to the artist—a state that would soon pass, and would not occur again. The dying lake was haunted ground, a memorial to the unintended consequences of human interference. It called for recognition of a passing state, a time of transformation.

I asked Sally about her working process—how she goes about familiarising herself with a place, whether she has a blueprint she applies wherever she goes, whether she looks for particular things.

To begin with she just walks around, she says—paying attention, tuning in, trying to be completely present, receptive to the nuances that are unique to that particular place. “I have no idea what I’m going to do, what I’m going to make. I collect things randomly, without intention. And at some point I look at what I’ve collected and start to play around, until something suggests itself.’

The loot Sally brought back from the lake floor to the studio included fish skeletons and scales, black plastic irrigation pipe and Lake Mokoan mud, the decomposing table cloth, scraps of rope and wire, aluminium drink cans, shotgun shells, turtle shells, water-bleached twigs and the skulls of small animals. To this eclectic mix of objects she applied the ideas and processes that have preoccupied her since the beginnings of her development as a sculptor.

Which brings us back to the museum and those controversial ethnographic collections. When I asked Sally what was at the root of her inspiration, she hunted out a quote from the sculptor Linde Ivimey, who replied to the question “Who inspires you?” with the following statement:

“Every unknown, tool-pushing, cave-dwelling, harvest-following person whose work makes up the ancient antiquities section in every museum around the world. The people who made things just to satisfy their urge, their spirituality, their god or their curiosity. No names, just a date followed by BC or AD and their objects for me to wonder at.”

Sally grew up in Adelaide, home to the South Australian Museum, which houses the most extensive ethnographic collection in Australia. As a child she was captivated by the Egyptian room, still one of the museum’s most popular exhibits, which contains a sarcophagus and mummy and all the associated regalia of death, the artefacts and votive objects that accompanied the dead into the underworld. And there were collections from Indigenous Australia, Oceania, Asia, Africa, the Americas. The objects carried a charge that spoke across time and culture to some universal need to pay homage, to propitiate, to harness or influence the unpredictable, unmanageable stuff that is inseparable from a sentient life. She recognised them as the artefacts of a generic human tribe to which she belonged. And the proximity of the museum to the art gallery reinforced the conversation between art and artefacts, encouraging the link between ancient objects and a contemporary sculptural sensibility.

The first objects to emerge from the Lake Mokoan series were three-dimensional sketches for the final works—figures made predominantly of irrigation pipe, with attachments of wire and rope and bone, their perpendicular black forms suggesting the trunks of the drowned trees. The tribe of small humanoids with their bone heads and ropy hair and dirty lace dresses made a nod towards the tribal fetish, a quirky fusion of the comic and the sinister.

- Sally Simpson, Artefacts: Lake Mokoan (scales). 2009–10, irrigation pipe, aluminium can, fish bones and scales, bell jar, 58 x 25 x 25cm, photo: David Paterson

- Sally Simpson, Artefacts: Lake Mokoan (rabbits), 2009-10, irrigation pipe, bones, rope, fishing tackle, shotgun shells, mesh, lace, mud, bell jar, 58 x 25 x 25cm, photo: David Paterson

- Sally Simpson, test object, irrigation pipe with mud and materials collected at Lake Mokoan, dimensions variable, photo: David Paterson

But they lacked the devotional quality, the sense of reverence that the transitional moment of the lake’s passing deserved—all those dead fish, the delicate orchestration of bones and scales and gills that could not adapt to the new environment—the collateral damage of human ingenuity.

What does she mean by devotional, I ask. What is her practice devoted to?

“It’s not devoted to a particular thing or idea,” Sally says. “It’s as much about process as it’s about the object—the rituals involved in collecting and sorting and preparing the materials, the hands-on, labour intensive techniques, the need for patience and focus. I’m a compulsive collector. I collect without intention, randomly, intuitively—ideas take shape alongside the objects. They feed into each other long before I know what I want to make, or why.”

“And what about your methods?” I prompt. “The stitching, the plaiting and wrapping and weaving?”

“My grandmother was a dressmaker. I watched her making clothes from the time I was a small child—drawing the pattern, cutting it out, making a practice garment out of calico, draping and shaping and adjusting until it had a structure, how the stitching was structural and ornamental at the same time—this extraordinary skill harnessed to the most ordinary purpose. I was captivated by the idea that you could apply this labour-intensive, devotional process to the everyday work of family. That the domestic and the devotional could exist in the same space, in the same process.”

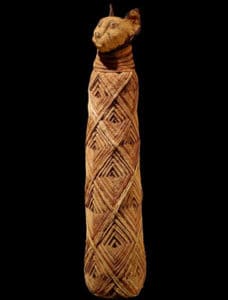

Cat mummy. Animal remains and linen. Provenance unknown, Roman period, after 30 BC, courtesy British Museum

And then there’s the imprint of the Egyptian room at the Museum, the mummified remains of Renpit-Nefert, a well-to-do middle-aged woman, 160 centimetres tall, who died around 2500 years ago. There’s the ancient hum of domestic Egyptian lives memorialised in museums around the world by the embalmed remains of aristocrats and their exquisitely bandaged pets. Making the work is a way of thinking with materials rather than with words. It’s a conversation between materials and technologies in which the artist is both a conduit and a tool. The idea emerges from the method, the method re-inforces the idea.

The lace-wrapped objects in Venerated Remains hover between votive and fetish, acting as metaphors for transformation from one state to another. The poly-pipe is no longer visible, but it provides the infrastructure, the gaping mouth in the fish skull, the hollow centre around which the fabric is wrapped and stitched.

Sally Simpson, Venerated Remains trio, 2012, three objects lace,fish bones and scales, mud, gold leaf on mirrored, aluminium base, 46 x 60 x 20cm, photo: David Paterson

At the simplest level the mummies suggest the transfer of dead fish to the afterlife, a homage to and acknowledgement of death and change. At a more complex level they speak to the link between ancient preoccupations with death and modern anxieties about the future; to an art practice that eschews grand statements and embodies the act of homage in the slow, careful processes required to make the work; to gathering up the discarded trash of a society dedicated to novelty and transforming it into objects of reverence. The purpose is to honour small deaths and ordinary lives and the state of flux and transformation they represent.

Around the time that Lake Mokoan was bleeding dry, Glenn Albrecht, Professor of sustainability at Murdoch University in Perth, coined the term solastalgia to describe “a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at home, but the environment is changed.”

The speed with which the term was taken up indicates that it named something that needed to be talked about—a feeling that combined desolation, nostalgia, and the need for solace—a state of existential sadness caused when a beloved place is changed in ways beyond our control.

Surely the Germans have a word for it, I thought, something that doesn’t sound like a gum disease, but the best I could come up with was heimwehtrost, which still sounds like a gum disease, in German.

Professor Albrecht has also suggested the term psychoterratic to describe earth-related mental health conditions.

“I want to contribute to an expanded understanding of the changing relationship between the states of biophysical and built environments and human mental and physical health.[…] Despite the importance of connections between environmental or ecosystem health and human health (physical and mental) in many cultures, we have very few concepts in English that address environmentally-induced mental distress, or conversely, environmentally enhanced positive mental health.”

As the Anthropocene advances and our environment changes irreversibly around us, this may be the moment when environmental scientists, philosophers, psychiatrists and poets need to pool their skills and come up with a language that speaks to the ear and the soul as well as the mind—to coin words with the cross-cultural heft of zeitgeist, or weltanschauung. Maybe this is the moment when we need to turn to Aboriginal languages, which are bound to have many more words to describe the feelings we have for place and loss of place as we know it. A quick scan of the dictionaries I have on my shelves offers some possibilities… home—ngurra, purlku, jalpu, yumpardi; homesick—watjilpa, yilaru, yirraru; to be homesick—kulpala, watjilarriwi; to be nostalgic or sad—waparrmarnu; to affect emotionally—kanyi-…

As we move further into the Anthropocene, the age in which global environmental change is driven by the activities of humans, it is likely, if not inevitable, that the places we know and love will be changed in ways we can’t imagine. In a secular culture, it is artists who take up the role of offering possible ways to express our deep fears and hopes. Sally Simpson is among a growing number of artists who seek to respond to the sense of loss people feel as the landscape of home becomes unfamiliar and broken.

Although she is hyper-alert to environmental issues, Sally is not trying to suggest solutions or prescribe actions. She sees her work as a way of teasing out her own thoughts and emotions, of finding a way to process the contradictions and channel the incipient panic. It’s a primitive attempt to influence the world, to appease, to plead, to propitiate, to draw attention to the desperate situation we are creating. Using the detritus of modern farming practices, she makes objects that belong to a continuous tradition of humans attempting to influence and manage the forces that affect the lands we live on.

Sally Simpson, Precipice, 2013-2015, 9 objects baling plastic, string, bones, human hair on steel and timber bench, 159 x 240 x 40cm, photo: David Paterson

There’s a question that begs to be asked, so I ask it.

“You draw on tribal and ethnographic material from everywhere except Indigenous Australia. Why?”

“Aboriginal culture is the only one I don’t feel entitled to reference. It’s forbidden ground, for the time being anyway. To draw on Indigenous objects would require treating them as unique and specific. I’m responding to something universal. I don’t feel the need to apologise for drawing on other cultures, whereas to draw on Aboriginal material calls up a whole other set of issues that I don’t feel qualified to talk about.”

There was a moment, working on the Lake Mokoan material, when she began using lengths of plumber’s pipe, only to abandon them when she saw that they resembled Aboriginal burial poles. At the same time, she felt no constraints about making totems from cattle bones sourced from her home on a small cattle farm in southern NSW, and using the most powerful of Christian symbols, the cross, although she insists that she uses the cross as an archetypal rather than a Christian symbol.

“The burial poles felt like a direct reference to Aboriginal culture, whereas the totems and the cross felt universal. I’m trying to work out how I feel and where I fit within the evolving relationship humans have with the land. My work is about what’s happening now, responding to the ongoing changes in my own immediate environment.”

How to negotiate Indigenous sensitivities around land and its meanings is something that settler artists deal with in various ways. Of those who have no direct experience of the Aboriginal world and no obvious way to engage with it, the choice most make is to leave it alone. There needs to be a pressing reason for an artist to venture into that risky terrain, and those who do engage are often driven to do so because their own lives have intersected with the lives of Aboriginal people, or their work leads them into that realm, or a chance encounter evolves into an ongoing relationship.

For Sally none of these circumstances existed, and she did not feel compelled to go there. Nevertheless, in 2014 she joined me and several other artists on a field trip to the Tanami/Great Sandy Desert region, and the remote Aboriginal community I visit every year, located on the edge of a terminal lake system called Paruku.

It was interesting to bring people from my other life to visit this one. Two had been here before, but for the rest it was a first. The trip was part of a project to see how the artists interpreted and were impacted on by the remote Aboriginal world. I had been visiting and working on the community for more than a decade, and had links to it that went back to my childhood when my family ran a cattle station in the region. I had not foreseen how difficult it would be to stretch myself between the two worlds. My friends and colleagues had spent great effort and a lot of money to get themselves here, and it was my responsibility to manage and interpret the place and people for them.

The campsite where we set up was exposed and windy, although the coolabahs at first and last light were beautiful, and the horizontal band of silver or blue of the distant lake was magical. This was another lake system, always changing, but here the changes were part of a vast natural cycle linked to the monsoon. But where exactly was the lake? I’d told people that this place was an arid-zone wetland at the junction of two deserts, a terminal lake system created during one of the ice ages, when the ancient channel that flowed to the sea was blocked by dunes laid in during a thousand years of drought. The shoreline was a couple of kilometres distant, just visible from the camp. There were times in recent years when it had been only a hundred or so metres from the campsite. This time it was more mirage than reality.

But the lake has many aspects, and I took my friends to sites where high water lapped the drowned trees that were evidence of decades when the water levels were much lower. We walked along the deep channels cut by the river that charges the system every wet season. Some years there’s a moderate flow into the lake, some years a massive flood that bleeds out into the desert and re-activates the boundaries of the ancient mega-lake. I tried to explain this, conscious that I had an embodied template of the shrinking and expanding of lake edges that had no meaning to the visitors.

In the end the people and their country worked its magic—the days of walking and driving with the Aboriginal women gave my friends access to the land in ways they could not have otherwise experienced, and for some of them at least it was a glimpse of how it might be possible to develop the connection further. But that would require the commitment of a great deal of time, and a willingness to roll with the unpredictable nature of such a relationship. For most of the visitors it was a brief immersion in a strange and beautiful land and a glimpse into another way of seeing and being.

Returning every year to this particular desert is something I do for personal reasons—I have known the people here since I was a child, and finding a way to articulate the complicated ground between white and remote Aboriginal Australia is central to my work as an artist and a writer. But I also want to share that relationship with my non-Aboriginal friends and colleagues, people who bring the best kind of curiosity to the work of teasing out an ethical and aesthetic understanding of country.

At the end of the trip I asked everyone to send me their responses to the experience. The two people who had been here previously, Wendy Teakel and Rachel Bowak, did not have to go through the shock of first impressions. They already knew how remote the location was, how different the culture, how unpredictable the environment. They were able to bring their own practices to bear because this place had already entered their awareness.

“Setting fire to country was very special and watching the kids lighting fire. Experiencing the predictability and unpredictability of fire o I enjoy the experience that I am not entirely in control. Landmarks like the lounge chair (a large termite mound shaped like a 3 seat lounge) and the TV (upside down rusted bucket on termite mound) named by the kids. Shirley showed me the plant which smells like apples and said it smells nice if you hang it on the kitchen window while you’re washing the dishes. These domestic moments re-contextualise the desert as home and garden.” Rachel Bowak, sculptor

“Looking for the spaces in between, cultures, knowledge systems, perceptions, trying to see and acknowledge the edges. Trying to get a sense of the texture, the friction and striation worn through grit. The patterns which are enduring—of wind, cloud, erosion, thinking of space knowing it is structured through culture to be place. Allowing it to be unselfconscious. Allowing it to be one place and many. Deciding to return deciding to know it better. Trying to make work that is dryer, grittier, aged. Trying to get the experience of bodily engagement not observed but felt.” Wendy Teakel, sculptor/painter.

Although Cathy Franzi had never visited this region, her ceramic practice, grounded in using Australian plants to suggest both form and decoration, gave her a way to interact with the unfamiliar environment. At a practical level she collected clay from different sites and fired it, with various results. The anxieties and discomforts caused by the disjunction between her expectations and the reality she encountered were mediated by her scientific approach.

“My understanding of country was vastly different to Aboriginal understanding of and relationship to country. Theirs permeated every aspect of their culture and history, and yet seemed without the reverence I expected. I came to see that my sense of reverence was culturally different to theirs. The experience of being shown the country from an Aboriginal perspective was incredible. Every plant and animal had multiple significance and uses, and they were connected in a cultural way in contrast to my understanding of the relationships of plants to the environment through the culture of western science.” Cathy Franzi, ceramicist.

All the men on the trip were called David. The entry into a different reality seemed to discomfit them more than it did the women—maybe the experience of not being in control had a greater impact on them.

So much red and a feeling of no place to shelter from the elements, nowhere to hide or escape from the cold wind then hot sun.

Over time I noticed more and more subtlety in the land.

Red soil, burning grasslands, termite nests.

The desire to burn was very powerful, I have not felt this before.

It was very satisfying to burn, the night fire event was thrilling and for me somehow a

natural way to interact with the place. David Suckling, ceramicist/designer

“I was warmed, impressed, at times awe-struck and sometimes saddened by things, situations, people and animals I came across, and the country itself… the toughness of the country, and of the life of the regular dwellers there, and the beauty alongside and within them. Manufactured things too have a tough life, and don’t seem to last long there.” David Keating, sculptor

“My overwhelming thought was that the landscape was like being on a different planet. In the end I liked finding the ‘particular’ about where we were. Although the country was vast, it was in the detail that I found connections. I was also acutely aware that if things went pear shaped, it would take a while to sort it out. The unknown around this made me feel vulnerable.” David Jensz, sculptor.

For Sally it was just a beginning, too little time to do more than wander and collect, and to observe how the Aboriginal women used the resources of their environment. While it added another layer to her fascination with the relationships between humans and land, it also reinforced her sense of the complexity and commitment involved in cross-cultural practice.

“…Shirley and Evelyn in all the locations we visited, the day at the school, the water and large bird colonies. Timelessness in every way. Moments alone in a burnt landscape. Slaughtered horses. The umbrella theme that carries through all my work – where do humans fit in the land, what values are assigned to land by humans? What species have the ‘right to survive’.

“Having heard Kim’s stories forever and having travelled other deserts previously, I didn’t expect to get any work done, as I usually take a while to soak in the country and ideas gradually come. I expected to be on the edge of water rather than a lake bed so was aware I still hadn’t quite arrived until we did get to the water’s edge. I quickly felt at home, which may be that I like tent and campfire living. Later the country and the women got under my skin so that I felt I wanted to stay or return.”

Sally Simpson, sculptor.

We never really had the conversation about what the experience meant to Sally. It was too soon to ask those questions of someone whose process required a deep level of immersion and an extended time to make sense of a place as complicated as this. Lake Mokoan exemplified the settler Australian proclivity to mess with nature, and offered a rich but uncontested narrative. Paruku was something else entirely, fraught with contradictions, subject to millennial climatic rhythms, cross-hatched with the trajectories of traditional and colonial stories. For someone with Sally’s approach, the requirements of her own rigorous process would dictate whether she could devote her energy to interpreting this place at the expense of the places to which she had a lifelong connection. Possibly she was prompted by the recognition that the water’s edge felt like home, but for the time being she has turned her attention to the littoral zones of her childhood, constructing objects from the flotsam and jetsam washed up on coastlines and beaches.

Sally Simpson, Jettisoned, 2016, fish bones, rope, shells, pearls, fishing line and hooks, 29 x 48 x 48cm, photo: David Paterson

Wendy Teakel had travelled to Paruku years ago with our mutual friend and artist colleague the late Pam Lofts, to visit me in the early stages of what would become an established part of my working life. She describes her relationship to the land as being an “existential insider”, a state defined by Edward Relph, author of Place and Placelessness, as a situation of deep, unselfconscious immersion in place. This approach acknowledges the Aboriginal presence while allowing for a personal, experiential response, opening up the senses to whatever is present in a particular place. Wendy grew up on a small farm in central New South Wales, the kind of place that demands everything you have to give, and gives back a bare living. But it teaches you how to hold the ground, make the work, and dig your heels into the earth that feeds your practice. Many of Wendy’s three-dimensional works would find a place in the museum of the future, evidence of a settler awareness of the land that is alert to its volatile fragility and its aesthetic force, earned through childhood exposure to the hard truths and daily enchantments of life on the land.

Wendy Teakel, Late Summer Haze, 2012, sticks, steel, grass, soot, ochre, 120 X 300 X 100 cm, photo: David Paterson

The mark-making in Wendy’s paintings and drawings has often led to suggestions that she draws on Aboriginal iconography, but she points out that the similarity comes from a similarity of process, from close observation of the patterns wrought on the ground by nature and culture. However, the affinities are evident, and her pokerwork methods of heating wire rods and burning marks onto sheets of plywood or heavy paper roused the curiosity of the Aboriginal women, who use the same technique to decorate wooden artefacts. They enlisted Wendy’s expertise to design custom-made wire brands with which they practiced making shapes on sheets of cardboard, before burning them into the surface of a wooden coolamon.

Successful collaborations between Indigenous and settler artists are becoming more common, one of the most notable being the recent collaboration between Fiona Hall and the Tjanpi Desert Weavers, a group of Western Desert women whose work leapt into the public domain when they won the Telstra Award in 2005 with a full-sized woven trayback Toyota. Fiona Hall is a natural fit with the Tjanpi weavers, who approached her to work with them. The work they made together was exhibited with Hall’s installation, Wrong Way Time, at the Australian pavilion in the 2015 Venice Biennale. In my constellation of Museums of the Future there will be a museum that is dedicated entirely to the work of Fiona Hall and the Tjanpi Desert Weavers. Visitors will be captivated and confused by the dialogue between the objects—monstrous masks and endangered marsupials woven from shredded camouflage uniforms, grass helicopters airlifting ringtail possums to safety, and the array of cabinets containing the highly organised taxonomies of a psyche that perceives connections within connections and meanings within meanings. What those future visitors will make of it as a reflection on the culture of 21st century Australia is anyone’s guess, but they will recognise the same wild inventiveness, the same dedication to process, the same need to channel energy through whatever material is to hand and give it form.

The collaboration between Nalda Searles and Pantiji Mary Mclean exemplifies the long-standing relationship that grows from an encounter that is part of the natural trajectory of a working practice. Searles was a well-established fibre artist and sculptor when she met Pantiji Mary Mclean at a weaving workshop, a meeting which resulted in a friendship and artistic partnership that was of great creative benefit to both artists.

Working with Mary Mclean freed Searles to go further and deeper into the terrain which she had already explored for many years. Many of the objects she produced for the exhibition Drifting in My Own Land, which toured throughout Australia between 2009 and 2013, would find a place in the Unknown Future Museum.

In her review of Drifting in My Own Land for Artlink magazine in September 2009, the words Holly Story uses to describe Searles’ work could as easily apply to Sally Simpson, and to the Tjanpi Weavers and Fiona Hall.

“…many hallmarks of her continuing practice are evident very early. A commitment to found, gathered and gifted materials; the use of ancient technologies such as coiling, twining and stitching; a fearless approach to building form; a belief in the well-made object; and a steadfast trust in the power of place to inform the work.”

I imagine a wing of the unknown future museum dedicated to objects that employ the same techniques, and arise from the same desires, anxieties and preoccupations, regardless of the time or the culture in which they were produced. I imagine these objects speaking across time to the fears and aspirations shared by humans since the beginning of our attempt to make sense of our place in the world. Some of the artefacts that currently cause such offence to indigenous people might find a better reception when they are presented in a context that reveals the legacy they have bequeathed to the future.

And the display of Anthropocene artefacts from early 21st century Australia, comprised of the work of both Indigenous and settler artists and assembled to illustrate waparrmarnu-ngurra, which translates loosely as “sadness for country”, will exhibit a spectrum of shared concerns and similar processes that will reflect the uncertain times we live in and the precarious future we anticipate.

Author

Kim Mahood is a writer and artist based near Canberra. She wrote the much-circulated essay Kartiya are like Toyotas, and is the author of Craft for a Dry Lake, which won several awards for non-fiction. She visits the Tanami/Great Sandy Desert region every year, where she works on environmental projects with the Aboriginal custodians. Her current project is to produce an Aboriginal seasonal calendar with the Walmarri traditional owners of Paruku (Lake Gregory). Her latest book, Position Doubtful – mapping landscapes and memories, will be published by Scribe in August.

Kim Mahood is a writer and artist based near Canberra. She wrote the much-circulated essay Kartiya are like Toyotas, and is the author of Craft for a Dry Lake, which won several awards for non-fiction. She visits the Tanami/Great Sandy Desert region every year, where she works on environmental projects with the Aboriginal custodians. Her current project is to produce an Aboriginal seasonal calendar with the Walmarri traditional owners of Paruku (Lake Gregory). Her latest book, Position Doubtful – mapping landscapes and memories, will be published by Scribe in August.

Comments

This essay makes me aware of the role of the enriching visual familiarity of place, i know both Lake Mokoan and Paraku, however am i also limited by this reality. I look forward to a second reading of this essay.