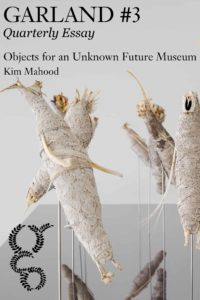

Sally Simpson’s Venerated Remains are powerful evocations of an ancient world, yet one that happens to be from a recent manmade lake returning to its natural state. Kim Mahood finds in Sally’s work an important expression of the non-indigenous relation to land, which reflects both the desire for a foundational history and the settler sense of non-belonging.

The essay begins…

The young Maori woman haranguing us from the podium had a tattooed chin and a story to tell, of a sacred object belonging to her ancestors that had found its way into a museum. She held us spellbound for fifteen minutes past her allotted time, giving us a view from the perspective of the collected rather than the collector, and stepped down, magnificent and unapologetic, to accolades and applause. The event was a Museums Australasia conference in Auckland about the relevance and future role of museums, and one of the most significant issues to emerge from the keynote speakers and panel discussions was the challenge museums face over their ethnographic collections—all those tribal artefacts and human remains, the masks and shields and spooky fetish objects gathered by scientists and explorers and adventurers. The descendants of the people to whom the artefacts and skulls belonged are demanding a say in how the collections are displayed and interpreted, and in some cases the return of certain objects, especially the human remains.

The historical contexts and the motives of the collectors are in the frame for questioning. Time has wrought a dramatic change on the meanings we attribute to the museum display and the interpretations attributed to the collections. The “exotic” and the “primitive” are stepping out of their display cases, emerging from their labelled shelves and drawers in the museum store-rooms, re-asserting their power and re-defining their meaning in the world.

One of the most thought-provoking ideas I took from the conference was the way in which contemporary indigenous people respond to museum collections with discomfort and anger, while many of us who belong to the non-indigenous baby boomer generation remember the sense of awe and magic those collections instilled in us.

Another significant strand was the question of how museums should address climate change and the environmental fallout that will accompany it. There was a consensus that museums must retain their capacity to ignite a sense of wonder, and in so doing make us care about where we have come from and where we might go. What a museum of the future might look like was subjected to the question of how far into the future. A hundred years? A thousand years? Ten thousand years?

To which I would add the question—what sort of objects will continue to speak to people in a thousand or ten thousand years? What artefacts will transmit meaning about the times we live in and the concerns that preoccupy us? If an object from ten thousand or a thousand years ago continues to speak to us now, then chances are those same qualities will communicate into the future.

The rest of Kim Mahood’s quarterly essay is available to subscribers here.