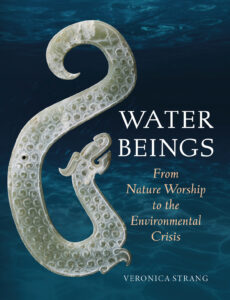

Artist Sasha Constable and her Otter Dragon created for the May Day festivities in Cerne Abbas; photo: Veronica Strang

Author of Water Beings, Veronica Strang, celebrates the appearance of Sasha Constable’s Otter Dragon at the Dorset May Day festival.

For many years, my anthropological research has focused on water deities around the world, and in 2023, I was delighted to be asked by filmmaker David Buckland, who leads the arts and environmental organisation Cape Farewell, to help create a new water being for the May Day Festival in Cerne Abbas, Dorset. In partnership with the Dorset Museum and the Dorset Science Festival, David had invited artist Sasha Constable to design a water being to celebrate the Cerne River, which is an important chalk stream and breeding ground for salmon, and therefore a focus for local environmental concerns.

Water beings are everywhere in early human history and remain centrally important in many indigenous communities. When all societies worshipped ‘nature’, supernatural deities personifying the creative powers of water were ubiquitous and deeply respected. Such divinities are typically serpentine in form, embodying the fluidity of water and its movements, but they are also hybrid beings, integrating the features of the local animal and plant species that they generate. And so the Dorset Otter-Dragon was born: a new water being revitalising old ways of celebrating human relationships with the non-human world.

For centuries, communities all over Europe congregated at ancient sites on May Day to celebrate the coming of Summer and the burgeoning of new life. Wearing crowns and garlands of greenery and flowers, they would rise to greet the dawn and conduct rituals drawing on Celtic Beltane practices and Greco-Roman veneration of fertility deities Flora, Dionysus, Ceres, and Aphrodite.

In Britain, May Day festivities brought together groups of Morris dancers wearing bells and ‘cloggies’ in wooden shoes. With much waving of handkerchiefs and clashing of sticks, they danced to music from pipes, tabors, accordions and fiddles. Leafy Green Men carried pig bladder balloons on sticks. Mummers wearing costumes of rags and riding ‘hobby horses’ performed plays, and a May Queen was crowned. Children, or couples hoping to conceive them, cavorted around a phallic May pole, weaving its ribbons together.

While these festivities waxed and waned, and the Christian Church redirected many Spring rituals into celebrations of the Virgin Mary and the birth of Christ, some communities continued to celebrate pagan May Day festivities. In Dorset, a major annual celebration takes place at Britain’s best-known fertility site, the Cerne Abbas Giant.

There is much debate about the origins of the famously priapic Giant, a nearly 60-metre-tall image cut into the chalk hillside. Some archaeologists and historians are convinced that it dates from the 9th century and that, armed with a large club, it represented the warrior-like Hercules, reflecting his inspirational meanings for the West Saxon army.

But all such imagery draws on multiple layers of the palimpsest that compose cultural landscapes, and there are other potential sources of inspiration. Another possible model is Dionysus, the major Greco-Roman fertility god equivalent to the Roman Bacchus. He is generally depicted carrying not a club but a thyrsus, which is a staff or sceptre entwined with a vine or a snake and described in classical Greek literature as dripping with honey. This might be a more logical object for a major fertility figure to wave about. Other candidates include a range of pre-Christian ‘green men’, including the ancient Celtic god of fertility, Cernunnos, depicted on the Gundestrup Cauldron made between 150 BCE and 300 CE, who may be the source of the village (and river’s) name.

The Gundestrup Cauldron with the horned figure of Cernunnos holding a snake. National Museum of Denmark

Whatever his – possibly multiple – antecedents, the Cerne Giant is a potent male fertility symbol. However, the Celtic religious landscapes that prevailed in Britain prior to the Roman invasion were characterised by gender complementarity, and avenues often connected (male) sacred groves or henges with (female) holy wells.

Sure enough, below the Cerne Abbas Giant lies an ancient holy well, traditionally believed to assist fertility. The Celtic landscape had many such ‘healing wells’, and people seeking help would tie ribbons to the surrounding trees or cast votive offerings into the water to call upon its restorative powers and to venerate the supernatural beings that they believed inhabited wells, rivers, lakes and seas.

In Dorset, such sites and their resident water beings would certainly have been important to the local Celtic tribe of Durotriges (‘water people’), to the Romans who conquered and enslaved them, and, later, to the Vikings who harried the British coast in their dragon-prowed ships.

Beliefs about ancient water beings, therefore, persisted in places like Cerne Abbas even as the Christian Church appropriated many holy wells. In a story that seems somewhat competitive with the well-endowed Giant above, Saint Augustine was said to have created the Cerne Abbas well by thrusting his staff manfully into the ground so that water spurted out in a great fountain.

In the ninth century, Saint Edwold, wandering around Wessex in search of a ‘silver well’ that had appeared to him in a vision, decided that the Cerne well was the one. He built a hermitage alongside it and lived there until his death in 871. In the tenth century, an Abbey was built upon the same site, and the avenue of trees leading to the well was renamed The Twelve Apostles. However, today, people still visit the well to tie ribbons to the trees and to leave votive offerings, and the largely pagan May Day Festival has become a major annual event.

The festivities begin at sunrise at the Trendle—an iron age earthwork at the top of the Giant’s hill—with dancing and singing by the Wessex Morris groups. The dancers’ costumes and flags are emblazoned with a red dragon. Also central to the event is a large horned figure described as ‘the Ooser’, whose headdress is reminiscent of images of Cernunnos.

Following the early morning dancing, singing, and some imbibing of refreshments, the participants parade down to the centre of the village. Here, the celebrations continue at a spot conveniently situated between several traditional pubs.

A somewhat more sober ceremony is held at the Holy Well to venerate the waters. These days the blessing is conducted by the local Vicar, Jonathan Still, but the event is ecumenical in encompassing references to Beltane, performing Celtic votive rituals, and expressing concerns about the environment.

In 2023, Sasha Constable’s Otter Dragon appeared on a main street leading into the village. Made collaboratively with members of the local community out of willow and papier-mâché, it was placed on a bridge over the stream in journalist Kate Adie’s garden, where otters can often be seen frolicking on the banks. A nearby text articulated the purpose of the new water being: ‘to champion our need to nurture the precious water that courses through our habitat and village like the blood coursing through our veins’ and to invite people to ‘think imaginatively about how to address and transform the environmental crisis that humans have caused, and find ways to turn the tide’.

Thus, the Dorset Otter-Dragon, in personifying the creative powers of water, joined the many old and new water beings around the globe being deployed to call out a very different kind of ‘May Day!’ for the world’s ecosystems and all the living kinds who depend upon them. Their message is clear: it is time for humankind to relearn ways to coexist convivially with the non-human world so that, rather than being a desperate call for help, ‘May Day’ can once more be a joyful celebration of life.

Photos by Veronica Strang, Sasha Constable, and The National Museum of Denmark.

About Veronica Strang

Veronica Strang is a British cultural anthropologist affiliated to the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography at Oxford University. Her research focuses on human-environmental relationships, in particular societies’ engagements with water, and she has conducted ethnographic studies in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Malawi. She is the author of The Meaning of Water (Berg 2004), Water, Nature and Culture (Reaktion 2015), and Water Beings: from nature worship to the environmental crisis (Reaktion 2023). Further information about her work is provided on her website veronicastrang.com

Veronica Strang is a British cultural anthropologist affiliated to the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography at Oxford University. Her research focuses on human-environmental relationships, in particular societies’ engagements with water, and she has conducted ethnographic studies in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Malawi. She is the author of The Meaning of Water (Berg 2004), Water, Nature and Culture (Reaktion 2015), and Water Beings: from nature worship to the environmental crisis (Reaktion 2023). Further information about her work is provided on her website veronicastrang.com

The Making of the Otter Dragon Sculpture

- The Giant Otter Dragon armature made with willow.

- Local families making mini dragon wings to wear for the May Day parade.

- Moving the Giant Otter Dragon from the village hall to install on the Red Bridge in the centre of Cerne Abbas.

Sasha Constable reflects on the broader community involvement in constructing the paper incarnation of Dorset’s legendary local water spirit.

I never thought I would create a giant modern mythological creature, but this is what I did in April 2023. Earlier that year I was introduced to Professor Veronica Strang who had recently published her new book, Water Beings: from nature worship to the environmental crisis. As a consequence, an idea was developed to create a contemporary water spirit sculpture with a connection to the village of Cerne Abbas, which could be included in the annual Cerne Giant Festival.

Not long before the inspiring conversation about water spirits, I had been shown some enthralling camera trap footage of a mother otter and two cubs frolicking around next to the Cerne River; it was from these images that the idea of an Otter Dragon was hatched. It seemed fitting for the Otter Dragon sculpture to be sited where the family of otters had been seen, so it was decided the Red Bridge would be the perfect perch for the Giant water spirit, empowering it to join forces in the cleansing and protection of the Cerne River.

Workshops were set up in our village hall over two weekends, during which villagers, adults, children and visiting friends helped to create the Otter Dragon under my guidance. The giant sculpture’s armature was made with willow and then covered in multiple layers of wet-strength tissue paper. It was then sealed with PVA glue, and lastly, details were picked out in acrylic paint. The sculpture took ten days to complete and was commissioned and funded by Cape Farewell.

The Cerne Giant Festival was inspired by Cerne Abbas’s magnificent Cerne Giant, a 180-foot tall figure engraved upon the chalk hillside overlooking the village. No one knows his true age, although recent archaeology indicates it may date back to 900 AD. Generations have been inspired by him ever since, and every May Day, Morris Dancers and villagers gather at dawn on the adjacent Trendle to salute the sunrise with dancing and a special Beltane beer. The festival was founded by Jane Still in 2017 and takes place over three weeks with a mix of walks, talks and workshops encouraging people to connect with the landscape and cultural roots of Dorset ‘Celebrating Humanity in the Landscape’,

About Sasha Constable

Sasha Constable is a British sculptor and printmaker, born into an artistic family descended from the English landscape artist John Constable, who is her great-great-great-grandfather. She completed a Sculpture degree at Wimbledon School of Art in 1992 and later earned a PGCE in Art and Design from Westminster College, Oxford. Sasha specializes in stone carving, often using limestone and, more recently, alabaster, and also practices relief printmaking. Her work is predominantly figurative, incorporating elements of the human form and architectural features. Between 2000 and 2018, she lived and worked in Cambodia, where she was deeply involved in the local art scene, teaching, curating, and coordinating large-scale art projects. Notably, she co-founded the Peace Art Project Cambodia, which transformed destroyed weapons into sculptures symbolizing peace. Visit sashaconstable.art.