Gary Wornell discovers Rabindra Shakya’s workshop of gleaming copper sculptures and appreciates its success in a country abandoned by its youth.

Inside Rabindra Shakya’s Image Atelier, the dark copper face of a Buddha towers above me standing more than four metres high on a steel frame. The eyes, half closed, stare at a space on the floor relaxed and in meditation. The workshop is the largest I have seen in Nepal: a hollow three-story high building in brick and reinforced concrete. A spiral staircase in one corner leads up to a series of narrow concrete walkways lined with copper sheets, parts of sculptures and poster prints of assorted deities. Below, the floor is covered in copper sculptures in various states of completion.

The noise of hammering is intense—metal on metal—sharp to the ear competing with the Hindi pop songs from the radio. At the entrance to the workshop craftsmen sit on wooden benches, their backs to the light, absorbed in their work, partly formed objects propped against polished steel formers. Rabindra’s brother is working on a large rectangular copper plinth, drilling holes into the bright metal and offering up small, carved copper details to check their fit. A woman with a grass brush walks across the open spaces sweeping up the dust as the sun streams in through the high windows from the south.

Rabindra comes from a long family tradition of metal workers. His family are direct descendants of the Buddha. The Shakya name comes from the members of the ruling aristocratic oligarchy that gave birth to Siddhartha Gautama. Rabindra learned his skills in small cramped rooms on the ground floor of the family home where his father and brothers worked and their fathers and brothers before them. In my journeys around Kathmandu, I had discovered many of these small workshops, shutters opened to the street, workers sitting on the floor crouched over and tapping into metal sheets. Stacks of copper lined the walls, black pitch in well-worn kettles smoked on gas burners. On cooler winter days they would sit outside on the street in the bright sun, fingerless woollen gloves keeping their hands warm, working until the light faded. Electricity was always in short supply in Kathmandu when I first arrived but these days hydropower provides the country with enough energy to sell to neighbouring countries. These days the lights are on and hammers are tapping until late in the evening. There are always younger boys standing around, engaged in conversation, laughing, learning: watching the hammer and pointed tools pick out the details, line by line. Apprentices often work from home. They have a chance to prove themselves on the smaller works before they can get a place in a studio like Image Atelier.

- Intricate details are hammered into the basic form supported on a base of pitch to prevent warping of the form.

- Buddha face in the making.

- Rabindra checks the look of a face he has been working on against the body of the work.

- A completed sculpture waiting to be gold plated.

- The Image Atelier workshop in Kathmandu creates remarkable detailed sculptures from copper sheet. Here the composite pieces are being assembled to form the back plate of a much larger work.

- Rabindra’s brother inspects the work being carried out on a plynth for a sculpture.

- Copper beating buddha statue

Rabindra’s business has been handed down from one generation to the next creating both Buddhist and Hindu sculptures for temples and monasteries as well as for private customers. They practise the traditional craft of Thodya (embossing in metal sheet) Majha (giving complete form) as it is called in Newari or repoussé as it is called here in the West. In Thodya Majha larger metal sheet is worked from the front and back against formers, and for the smaller details the chasing method is used from the front of the object supported by a hardened pitch mould.

But things in the Shakya family tradition are changing rapidly. Covid has taken the life of a close family member and his elder son, a son who traditionally would have inherited the craft, is at University in Queens, New York. The young are leaving Nepal at an alarming rate of roughly 800,000 a year. Many are leaving for higher education in Australia, North America and Europe. The 20-35-year-olds are abandoning the land of their birth and the traditions that have been in place for millennia, for opportunities abroad. Most of the graduates relinquish their citizenship with no intention to ever return. Others, the less economically fortunate and poorly educated, leave their wives and children in their villages to work as construction labourers or hotel staff in the Middle East. Nepal’s brain drain has already had a drastic impact on the development of the country and along with the loss of skilled craftsmen and women, the country will increasingly rely on the revenues of tourism and the single immovable feature that draws millions of tourists a year: the Himalayas.

- Detail of a wall piece made from copper and intricately painted.

- A wall piece made from copper and intricately painted.

- Gold plating is done by specialists in another workshop and polished to a high gloss.

- Gold plating is done by specialists in another workshop and polished to a high gloss.

- Face painting is an art done by another workshop specialising in this craft.

Rabindra’s reputation is such that, unlike many of the highly skilled artisans in Kathmandu, he has been able to travel abroad and grow his business, making statues for Buddhist monasteries around the world. A few years ago I curated an exhibition in Finland featuring the works of several craft legends from the valley, and when the museum sent letters of invitation to each of the craftsmen and women featured in the exhibition, Rabindra was the only one out of seven that was granted a visa for the opening ceremony.

Inside Image Atelier, set back from the road, the rhythmic tapping of hammers echoes against the high white painted brick walls. On each of my frequent visits there were new things to see: the large copper statue in the corner, unfinished on my first visit, had been sitting here for more than a year and was now covered in a soft white cloth protecting the immaculate gold-plated surface. I asked Rabindra where this magnificent sculpture was going and he smiled and said that the client had ordered and paid for it two years earlier but had never come to pick it up!

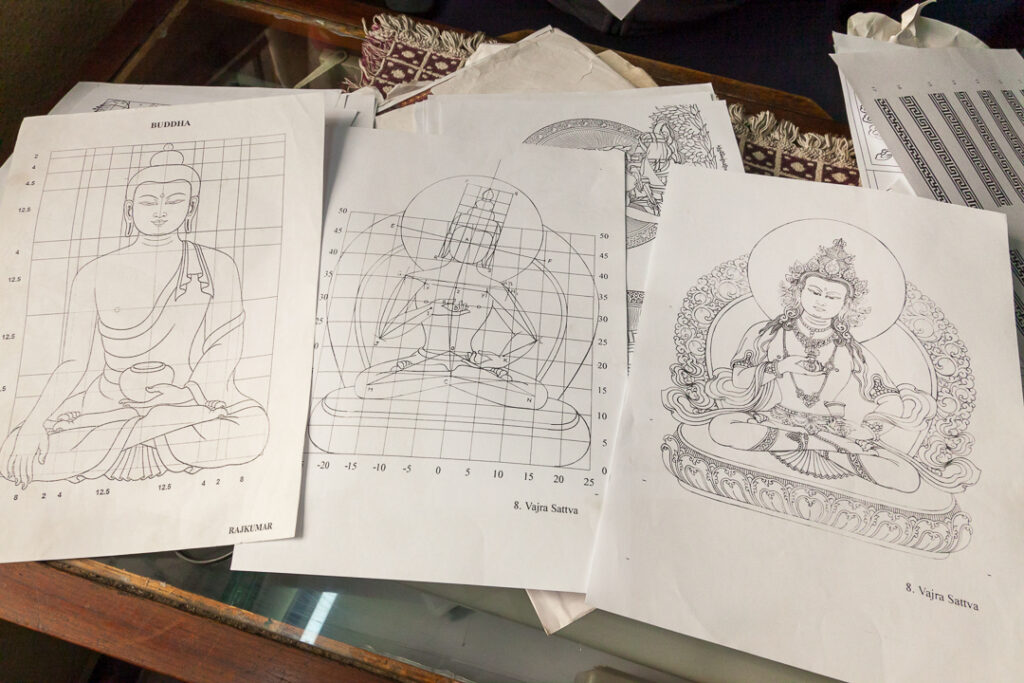

Everything they make starts with a drawing.

In the office stacks of drawings are rolled up in a corner behind a sofa. Everything they make starts with a drawing. Rabindra tells me that to make good work, the drawing should be excellent. The complex forms follow strict geometric rules and yet when the work is complete one barely notices the matrix of triangles, circles and rectangles that are the foundations of the statue. It’s all about symmetry and balance. As for most of the Nepali craftsmen I met engaged in the making of statues, it is the face that reflects the deepest meaning in the work.

Above the workshop there is a small kitchen where the family have their lunch and tea is made for visitors. Next to that, further along the raised walkway, is his private studio where smaller sculptures take shape away from the busy workshop below.

Cross-legged behind a small wooden table he starts his day here, sitting on the floor under the window while the sun is bright. A row of metal formers is neatly arranged beside him on a solid wooden block. Today he is working on the face of one of the bodhisattvas, which I imagine will be Vajrapani with his third eye, though I can’t be sure. He works intently as I watch, constantly turning the head and hammering the bright metal in quick sharp taps as the mouth takes shape. It seems that everything he does follows a direct path from his head to his hands. The shapes grow stroke by stroke as if a vacuum formed out of the image in his mind.

Rabindra employs more than twenty people these days: some working in the workshop and some at home. Each has their own areas of expertise from paper drawings and sheet cutting, to carvers, wax workers, embossers and polishers. He has enough work for years to come, working only to commission these days with orders from around the world. Out in the workshop, I spent time watching the craftsmen at work. There are no women here. It seems to be a craft exclusively reserved for men in Nepal, though Rabindra has taught one American artist the technique, a rare opportunity for anyone from the West to learn from one of Nepal’s most highly respected masters of the art.

Taking a break from his hammering, Rabindra heads down the spiral stairs to the workshop floor and I’m left alone for a while as he inspects the face of a Buddha soon to be attached to the body of a large standing form. As he holds up the head where it will join to the body, inspecting the fit of the neck to the shoulders, I notice how similar the facial features are to his, the mirror image of a man, a direct descendant of Gautama, who seems deeply satisfied with his life’s work.