- Detail of Dibiyo-Wala Bagh, photo by Gopika Nath

- Detail showing stitching, Bagh embroidery with bach, photo by Gopika Nath

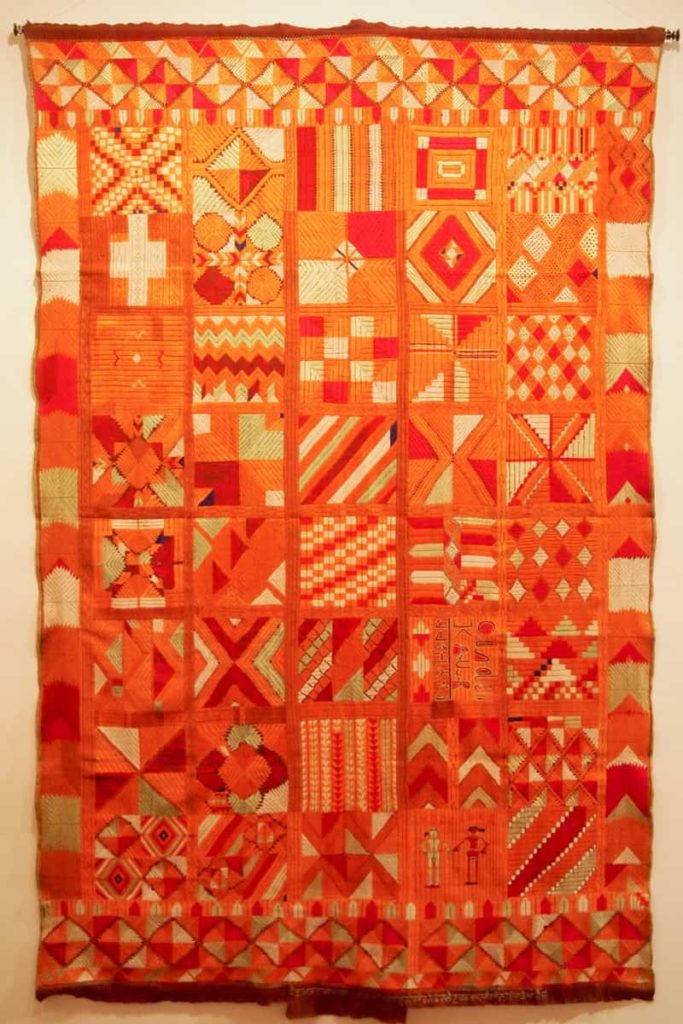

- Bavan Bagh

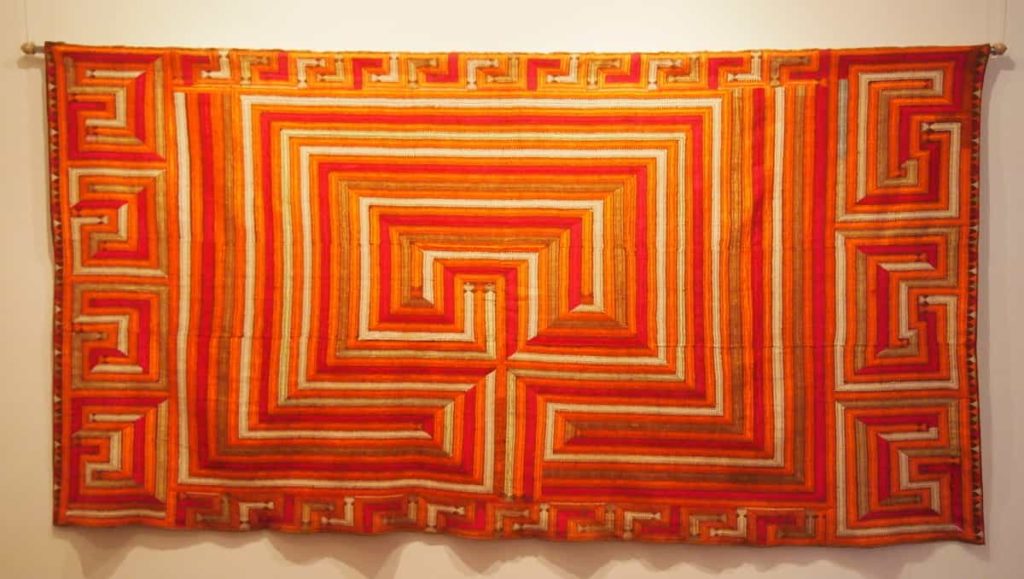

- Darshan Dwar

With threaded needle I embroider

Passersby question my tears

My marriage arranged, no longer

will I belong, but a foreigner be

– Phulkari Song, Balran, Sangrur

[you can also download this essay as an epub or pdf]

Sangrur, Punjab

Head bent, dark strands of straying hair neatly clipped on the top of her head, her eyes were focussed on the fabric stretched within an embroidery hoop held in her left hand. The right hand pulled a fine steel needle, threaded with a bright turquoise thread of shiny rayon, outward, to the far right of her shoulder, through a coarse vermillion coloured fabric, then back down into the fabric and out again. This rhythmic hand-dance was enacted whilst Nisha sat crossed legged along with a handful of young girls and women, on an old dhurrie laid out on the cement floor, in a rehabilitation centre run by ‘Building Bridges India’, in the Sangrur district of Punjab. This centre is located within the compound of the local Gurudwara in Balran, in the Moonak Tehsil of Sangrur, and these women come here to learn the art of Bagh and Phulkari embroidery.

Why were these women in a rehabilitation centre? Why were they even learning an art that has traditionally been handed down from mother to daughter, in this formalised way? Sangrur, a primarily farming district, suffered considerable loss through mass suicide of farmers. With at least one suicide a day for years, the numbers were staggering and often left illiterate and malnourished women, both young and old, burdened with their husbands’ debts, without any means of earning. This Centre sought to rehabilitate these women by teaching soft skills such as Phulkari work, which despite its deep cultural moorings had come into decline. However, Nisha and the other women I met with her were not victims of the mass suicides that Sangrur had been witness too. These women came to learn a skill. It was not specifically about seeking to learn the traditional art of Phulkari that their mothers and grandmothers no longer practiced, nor could teach them. The skill was desirable as it could provide income and some independence through this.

Cultivating an Interest

- Balran village fields, 2015, photo by Gopika Nath

- Bathing the buffaloes at the Toba, Balran, photo by Gopika Nath

- Wheat ears mowed down by the rain, 2015, photo by Gopika Nath

Historically, embroidery holds a very special place in India and there are so many different kinds of stitches that are classics. Ever since I started embroidering and using this as an artist, beginning in 1995, I have been keen to research, write about and learn as many stitches as I could. It was with this curiosity that I visited the exhibition of Phulkari at the Indira Gandhi National Centre of Arts, New Delhi in 2013. Although I am Punjabi by virtue of my cultural antecedents, I have never lived in Punjab, nor was I familiar with the traditional embroidery of this region. This exhibition piqued my interest, which was not as much for the embroidered shawls or chaddars that were on display, nor the catalogue text as anticipated, but for the women who were there to demonstrate their craft. In talking to them, I became intrigued about the art of Bagh and Phulkari and also felt a deep sense of regret for not knowing much about this craft or its tradition—a lapse that I sought to make up for, through the study and research I began then and have continued since. I had never been to rural Punjab, but in my quest to know more, to meet more artisans who did this embroidery, I embarked on this journey to Sangrur. I had as my guide Harinder Singh, who is passionate about Punjabiyat or the culture of Punjab and also collaborates with the Centre run by Building Bridges; and Abhishekh, a young video-film-maker who was helping me record this journey, in collaboration with Still Waters Media/ Bringhomestories.com.

Travelling through the rural landscape of Punjab in the month of February when unprecedented rainfall had mowed down the wheat crop, the poignancy of the centre I was about to visit was brought home. Rain lashed against the car window pane, and on both sides of the road, field after field of tender green ears of wheat were lying on their side instead of standing upright. The turbaned, Sikh taxi-driver interrupted an otherwise silent journey with intermittent, sombre comments about the incredible loss this would be to the farmers. The precariousness of their fate governed by unpredictable weather, now more than evident, was something I was now better able to empathise with.

Phulkari, literally meaning flower-work, was once the celebrated art of rural Punjab. While the original work is called Bagh, where the fabric is completely covered with thread work, Phulkari work draws its technique from the Bagh embroideries, but is much lighter and the motifs and stitching are sparsely dotted over the shawl or chaddar. A lot of excellence in Indian traditional crafts has been lost in time as a rural economy transformed into an industrial and now digitally-driven one. But, none has met with quite the same fate as Phulkari.

A daughter of Punjabi families, on both sides, and an embroiderer at that, I don’t know Phulkari work, but I am adept at cross-stitch and other such stitches passed on through the Irish nuns at the convent school I studied in. I later picked up Kantha, which is the running stitch embroidery of Bengal and have even tried my hand at Zardozi or metallic thread work, but didn’t consider learning Phulkari. Basically, I had never seen this embroidery being done around me, nor was anyone wearing this embroidered fabric, as I was growing up. I had been prodding my mother, now in her eighties, for information ever since I had seen the exhibition at the IGNCA. She never had anything to share and would get tired with my persistence. But then one day, when I walked into her room wearing a brightly coloured Phulkari, which I had picked up on some recent travels, she chided me for not getting her one. And then, as she held the embroidered fabric in her hands, fingers caressing the threads, admiring the fabric, my mother voiced a lament. She said that Phulkari was never really valued much when she was growing up. My grandmother, she revealed, had more interest in cooking than embroidery and the only Phulkaris she could recollect in her childhood years, were a couple that served as covers for large steel trunks used for storing the family woollens during the long and hot summer months of Delhi.

Re-Presenting Phulkari in the Contemporary World

The limited practice, of a rather diluted version of the rich repertoire of motif and the passion that had been prevalent in undivided Punjab, had not been vibrant enough to draw my attention as professional textile designer. And, as a matter of fact, it was not until 2013 that the fashion world even took note of this embroidery crafting tradition, when Manish Malhotra’s Autumn/Winter collection Threads of Emotion showcased Phulkari and Bagh work in Western and ethnic wear for both men and women. In the same year, he also designed the wardrobe for actress Kareena Kapoor, using Phulkari embroidery, for the Bollywood film Jab We Met.

It was also 2013, in April, at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts in New Delhi, that I met some women who had travelled from Tripri, the modern-day hub of Phulkari-work, near Patiala. They were in Delhi to demonstrate this art. All of them said that they had learned to do Phulkari embroidery out of choice, to fulfil an aspiration, but today, they did this work out of necessity and only to earn and keep a roof over their heads. Each had stories to tell about errant husbands and hardships borne. Bakshi Rana and Parvati Maasi had come to India from Pakistan at the time of Partition and had stories to tell about that too, even though they were very young at the time. The embroidery done by them during the demonstration was very sparse and mostly used the Holbein stitch employed in Chope rather than the fuller darning stitch of the rich Bagh thread-work of yore.

Later that same year, another exhibition entitled The Sacred Grid was curated by Jasleen Dhamija and displayed at Gallery Art Motif, New Delhi. The embroidered shawls or wraps were culled from the collection of Chote Bharany, showcasing some exquisite examples of the kind of craftsmanship that this art-form had seen. Mr. C. L. Bharany grew up around historians and collectors such as Stella Kramrisch, Dr. Moti Chandra and Karl Khandawala, to name a few, developing a fine sense of appreciation of Indian art. And today, he owns one of the finest collections of Baghs and Phulkaris that were done in nineteenth and early twentieth century, undivided Punjab. In 2014, the National Museum in Delhi showcased the Bharany Collection which had been donated to the Museum in 1976. A Passionate Eye, curated by Giles Tillotsan, featured textiles along with paintings and sculptures with some vibrant Phulkaris among them. All of this was instrumental in inspiring me to know more.

The Romance of Embroidery in Punjab

Jasleen Dhamija is a well-known textile historian and also a family friend—in fact a childhood play mate of my mother. Her personal history and involvement with the art of Phulkari, with memories of her grandmother in Abbotabad (Pakistan) a direct contrast to my own mother’s recollections, became added impetus and inspiration for my continued research of this art, especially from the perspective of an embroiderer. Jasleen recounts her grandmother daily spinning cotton yarn, for weaving the fabric that would later be embellished, while reciting the Gurbani or Pothwari songs from her childhood—of fondly selecting the coloured silken threads bought from itinerant Afghani sellers, before deciding on the designs to be embroidered. Dhamija brings her nostalgia for the craft and its romance in the by-gone years, telling us of stories and songs sung by the women as they sewed, through which she creates a rich narrative of the atmosphere and engagement that lovingly crafted these thread-masterpieces. This fount of lore is a distinctively variant to the stories told by the women embroiderers that I have met.

Jasleen tells us that Bagh embroideries, from which Phulkari is derived, emulate and re-create the chowk – the multiple squares which create the grid that houses the nakshatras or nine planets, which traditional astrologers tell us govern our lives. This sacred grid is the base upon which the altar, the temple, the church and traditional townships were created. In the case of the Baghs, the base of the woven cloth—its warp and weft—is the basis of the sacred grid upon which the embroiderer created multiple squares, within squares, creating a rich and powerful pattern. There are few women alive who can tell us what significance these lush fabrics actually had in their lives. Some researchers are sceptical about any significance at all, citing that if these were indeed considered family heirlooms, they would have been handed down the generations and therefore we should be able to see them in the villages of Punjab. But most villages don’t have any of the elaborate Baghs to show. What pieces we do see form part of connoisseur collections or are available in stores such as 1469, who have a small presence in New Delhi, Chandigarh and Amritsar. These Phulkaris that are available for sale in the stores have been purchased from old Punjabi families who no longer had any use for them.

With a Song on Their Lips

In Sangrur, I met seventy-five-year-old Karnael Kaur who recounted doing Phulkari as a young girl. She said that she had inherited about twenty and made about five of her own, but had distributed most as now there was no real value for them. She said that people were not interested in the elaborately decorated Baghs but preferred to be given clothes. She brought two pieces to the Centre, to show us, but they were rather sparsely embroidered. She also narrated that as a young girl, embroidery had been a daily ritual. Each day, after completing the household chores and tending to the buffalos that each family had in their homes, she, along with her cousins and sisters, would sit in the village court yard Pind ke gate ke peeche [behind the main gate of the village] singing and sewing. The rhythmic movements of stitch-work lend themselves well to singing, and throughout history the women of Punjab have embroidered with a song on their lips.

Phulkari Song

In 1984, while working on a college assignment, I came across the writings of historian Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, whose thoughts on the practices in ancient Indian art became a strong influence. It was not until much later that I was actually able to understand his ideas, but the impression held strong and as I matured as a textile designer, I began to understand the significance of the things he wrote about. He stressed that the “inseparable unity of the material and spiritual world”, such as is evident in the story narrated by Karnael Kaur, was the foundation of Indian culture that determined “the whole character of her social ideals”. He said that the artist was not a special kind of person, but everyman a special kind of artist, otherwise less than a man. He tells us that Vedic art was practical, where the “carpenter, metal-worker and potter and weaver provided for man’s material requirements” and that poetry was also practical, “designed to persuade the gods to deal generously with men.”

Stepping back in time, listening to Karnael Kaur reminisce about her childhood reveries as she worked with needle and thread, I imagine women in every corner of Punjab, stitching the poetry of the songs they sang as the poetic of thread. I see them in my mind’s eye, just like young Nisha in Balran, concentrating with utmost attention, counting warp and weft threads, inserting the threaded needle in and out, in and out, with a song on their lips—not unlike a ‘dhyaan mantra’ where worshippers invoke a chosen deity, offering prayers and themselves as devotees in service of the deity.

A Bagh exhibited at ‘The Sacred Grid’ exhibition, that made an impact upon me, was the mysterious labyrinth or ‘Bhul Bhulaiya’ Bagh. It was a richly coloured shawl [48 x 98 inches, 222 x 250cm] from nineteenth century Punjab and the words of this song were displayed alongside it

Meh bhul gayi

I have lost myself

Meh ous di yad

I have flowed

wich dub gayi

into his being

The song voices a sentiment that reflects a longing to merge with the Divine. Immersed in creating a complex rectangular-like coiling form, someone’s plaintive voice, soulfully singing, of losing herself and flowing into his or its being, was the almost audible whisper of threads, tenderly laid, so closely together. Embroidered with untwisted silk in colours off-white, saffron, yellow and a pinkish-red, more magenta than crimson, it was a reflective piece. I could not just admire its skilful embroidery, it made me think much deeper than the colourful threads laid on the surface of the cloth.

It is curious that a labyrinthine form would become something to reflect upon. However, this labyrinth was not just a simple coiling form that started from one point, around which lines and then more lines were encircled. This sharp-edged, almost rectangular-shaped coiling form actually had three parts, all of which commenced at a central point in the shawl and each line then worked its way around this. The three-pronged coil made me consider if this was indeed the work of a solitary maiden or if three women had worked upon it together. A dramatic change in colour, of the lines, from red to white or yellow to white, at the sharp angle where the lines turned, added to the complexity of the labyrinth. And, in trying to fathom which began where, the viewing eye did lose its focus, compelling a moment of almost involuntary reflection upon the self. At least that was my personal experience as I looked at this piece, admiring its many facets.

The Essential Fabric

History tells us that the plains of Punjab were rich cotton-growing areas and almost every village had a settlement of weavers who wove the hand spun yarn provided by their farming neighbours, in exchange for agricultural produce. Spinning was a household occupation. This tradition, of the craftsman as “an organic element in the national life, as a member of a village community”, as mentioned by Coomaraswamy, continued to some extent, well into the early 20th century but gradually fell into decline.

The untwisted skeins called pat that were used as embroidery thread for Phulkari work, were imported from Afghanistan, Kashmir and Bengal. This silk was expensive and therefore not wasted on the reverse of the cloth. Looking at the backs of the densely embroidered Bagh chaddars, one can see minute, intermittent, sparse stitches, making it difficult to imagine the richness of the embroidery on the other side of the fabric. To evolve a skill of this nature and cover a large fabric, usually 4 x 8 feet (122 x 244cm) in dimension, in lush thread-work with precision and skill, implies that this art evolved over many, many years of carefully considered workmanship. Its loss is all the more heartfelt because of this.

The stitches were made by counting the threads of the woven structure of the cloth and were typically made at right angles so that the embroidered patterns reflected light, according to the direction of the stitches. Although difficult to imagine through static photographed images, the gentle folds and crease of the shawl when draped, would heighten the quality of light reflected off the silken yarn. And this is seen to optimum effect in the patterns of the Chandrama Bagh and Dibiyo-wala-Bagh. Although the basic stitch was a darning stitch, a Holbein stitch was also used for the Phulkari called Chope and several other stitches were also employed for outlining motifs and edging the piece.

The Chope and Sainchi Phulkaris

The Chope with its double-sided architectonic pattern, temple motif and bold, stylized peacocks is quite distinct from other Phulkari and Bagh embroideries. Stitched with golden-yellow thread on a maroon khadi background, the resplendent peacock associated with marital love, longing and desire, calls out to its mate and to the dark, hovering clouds to bring rain and fertilise the earth. Writing about this Phulkari style in the Sacred Grid catalogue, Dhamija tells us that the Chope is also associated with the rainy season when the peacock calls out to the dark clouds to descend to the earth and fertilise it.

Sawan da mahina In the month of rain Mor kare shor vay the peacock cries incessantly Jiya mera asia nache My heart dances, not unlike Jaise nila more vay the blue peacock [Its longing for union with the beloved is implied]

Despite the absence of the dazzling hues of peacock feathers in the maroon and gold Chope, its pattern recalls the essence of this folk song, which was more than likely sung by the women as they sat together, each creating their own tapestries of desires to be fulfilled or expressing a longing that matched that of the yodelling peacock.

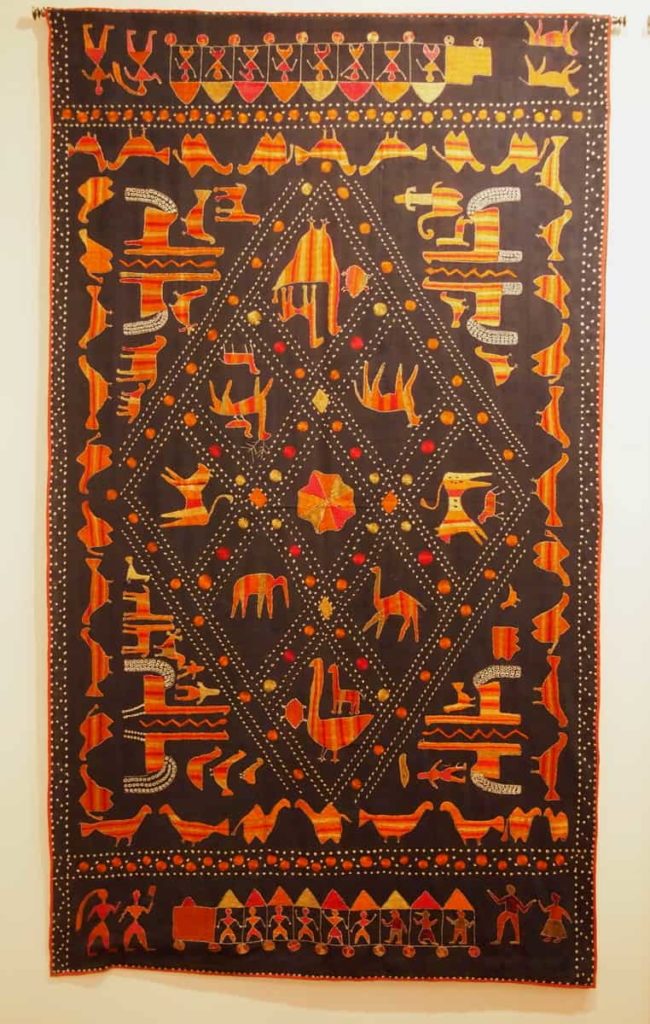

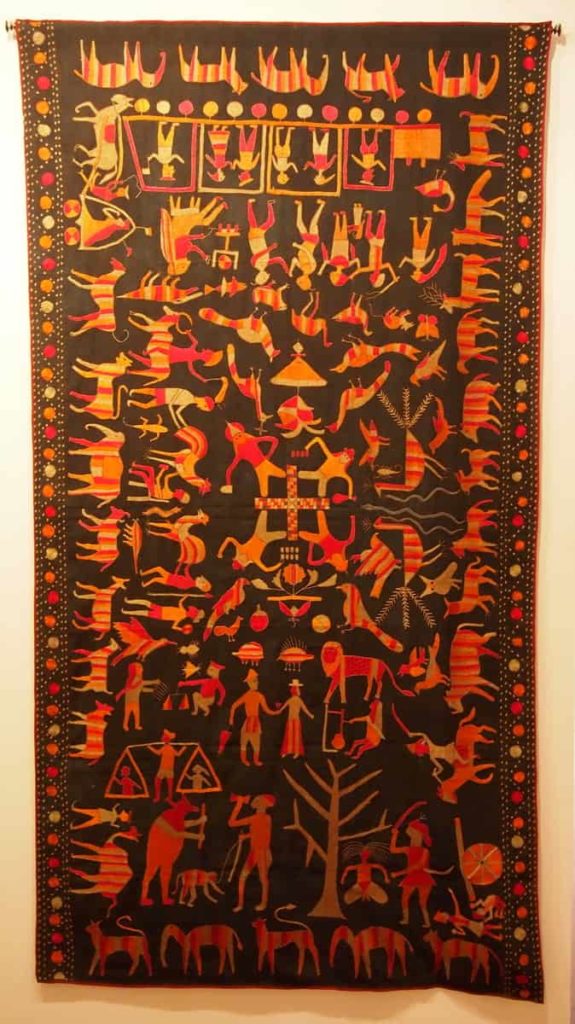

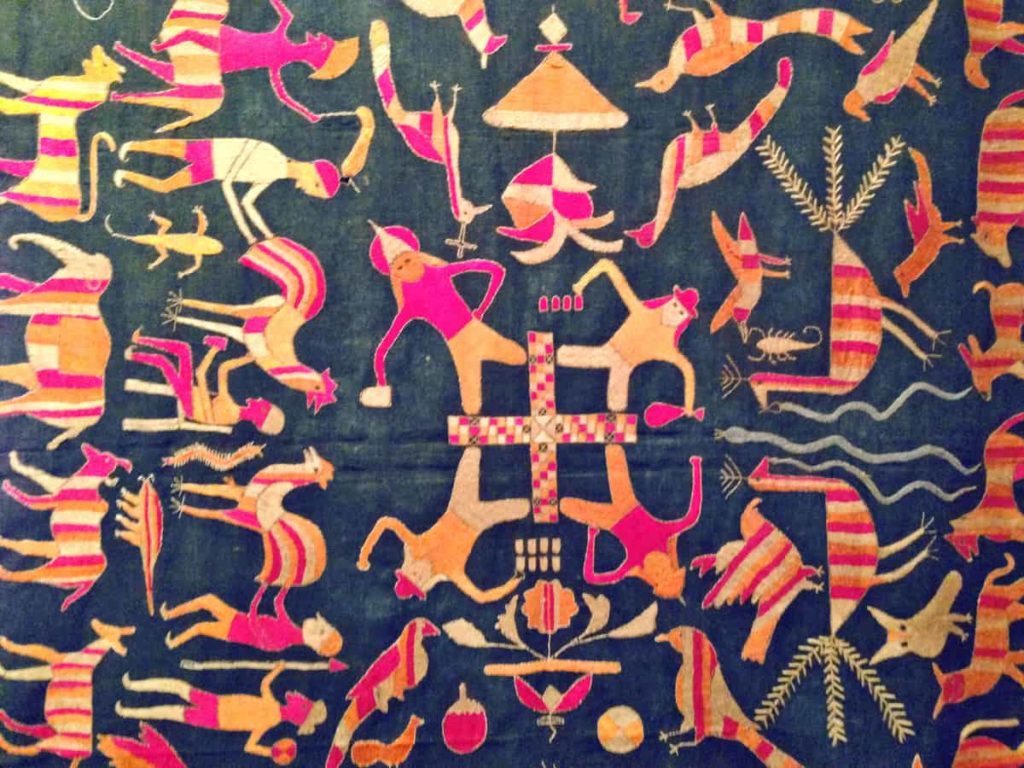

- Sainchi

- Sainchi

- Detail of Sainchi Bagh, photo by Gopika Nath

In my research into Bagh and Phulkari embroideries of Punjab, studying the various designs and patterns, I have come to liken them to paintings with a narrative that is either abstract or in the manner of naive painters. They are filled with stories – untold stories, stories creatively presented or those that could not be told, but stories that unfolded in the lives of the women that embroidered them and the families they embraced and which embraced them. While Muslim women followed the dictates of Islam in eschewing any kind of figurative representation, Hindu women were not bound by any such code which allowed them to create figurative pieces such as the Sainchi Phulkari. This type of Phulkari, was done by the women of Haryana and East Punjab and was closely linked to the mother goddess locally known as Sanjhi. She is associated with agriculture and is worshipped during the Navratras – nine days and nights of worshipping the goddess. The women created the presence of the goddess on the walls of their homes with colour and clay tiles and she was also the inspiration behind the Sainchis. These wraps which depict daily village life with its trials, tribulations, joys and aspirations are unlike the geometric and abstract patterns on Bagh chaddars.

The elaborate geometrical designs seen in the embroidered Baghs reflect the Islamic restraint on drawing of figurative form. However, Sainchis incorporate human figures, animals, flowers and birds, presenting a rich repertoire of designs depicting scenes of everyday life. These are interspersed with stories of epics and myths as well as personal aspirations and desires. Each design is an individual work of art, together forging a collective voice of the region. These needle-worked tapestries incorporate elements of social and national history as well as denoting images of progress that bring in colourful imagery of railway-trains carrying people. Some even include aspects of colonial life and the integration of the British into everyday life of the Punjab region, such as playing a game of Chopat with the locals, where even Gods participate. Some Sainchis also portray scenes from local legends such as the epic love story of Heer and Ranjha, whose romance is associated with Sufi traditions, as well as that of Sassi and Punnu. While the Baghs with their more geometrical patterns are reminiscent of abstract paintings, the Sainchis are more like visual folk-tales rich with historical events and a cultural past. I find that the two deviant styles complement each other and lend insight into how cultural differences coexist.

A rare Sainchi on an indigo background, from the Bharany collection shown at the Sacred Grid exhibition, 2013, is embroidered to simulate the dotted bandhani or tie and dyeing technique where peacock figures are featured in pairs with snakes between them. Traditionally this represented the sun and netherworld. Peacocks are sun-birds, also considered the enemy of snakes. While the Baghs are sublime in their abstract representation of the grid, the Sainchis are brimming with details of human life—everyday activities of the household interspersed with jugglers, wrestlers, mendicants and British officers along with myths and legends. Another unusual and bold Sainchi depicts the presence of the mother goddess Shakti through the use of lions—her vehicle or vahana. It is hand-sewn on madder-dyed khadi and has a profusion of men, women and animals. Pink and saffron dominate the colour palette with occasional threads in yellow and off-white. The overall effect is visually quite compelling even though the imagery is naive and does not have quite the sophistication of the Bhul Bhulaiya [Labyrinth], Bavan Baghs [of fifty-two patterns] and Darshan Dwars, which recreate doorways to worship. In another Sainchi with an unusually large lotus motif in the centre representing the sun, the embroiderer has added a clock to the mix of figures in the central panel, depicting a desire to control time or perhaps inspired by the novelty of a newly acquired item. A range of jewellery that dots the cloth canvas could be indicative of longing for what she does not have. These sewn, thread jewels form an elaborate ghungat that is to be worn across the forehead.

Despite the romance surrounding these embroideries that celebrate country life, human and soul union, the Phulkari chaddar was not a delicate fabric. As mentioned earlier, the plains of Punjab were rich cotton growing areas. Spinning was a household occupation and the weavers in each village wove the hand-spun yarn, provided by their farming neighbours, in exchange for food. The fabric was woven on a basic pit loom. Whether or not the coarseness of the fabric was intentional or something that the women made the most of, in terms of using the openness of the weave to do “counted thread work”, is not known. This robust, thick, almost coarse fabric was needle-crafted with untwisted silk. And the fine-craftsmanship of the embroiderer’s needle, as she counted each thread of the warp and weft before inserting it to lay the lustrous silk on the fabric’s surface, never lets us see this coarse fabric without intent. Traditionally, four colours of khaddar were generally used and each colour had its own significance. White was used by old women or widows, young girls and brides-to-be wore red, while blue and black were kept for daily use. Three to four narrow loom cloths were joined to form the complete shawl, typically 4 x 8 feet (122 x 244cm) in size. In some areas, particularly West Punjab the strips were first embroidered and then joined. In East Punjab, the panels were usually joined first and then embroidered across the whole cloth including the seams, for a more coherent design. The predominant colours of silk used were gold and ivory – referred to as marigold and jasmine, or wheat and barley – reflecting the agricultural tradition of the region.

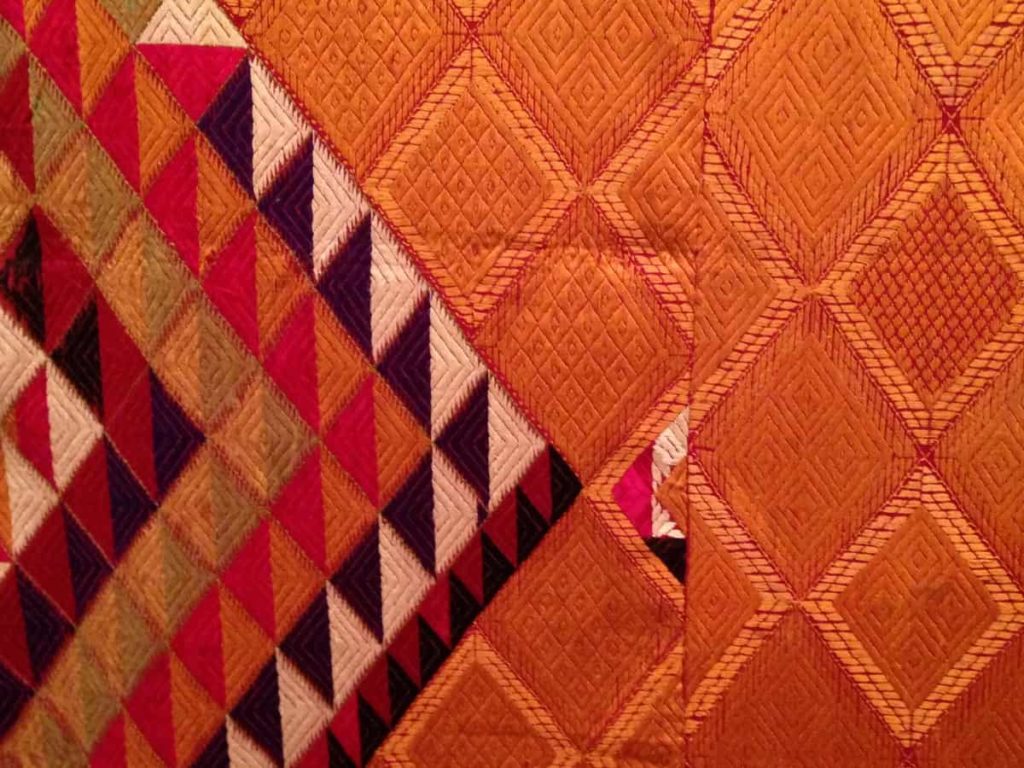

Thirma

In north Punjab, another tradition developed which was known as Thirma, signifying a white coloured base fabric. This was made exclusively by Hindus and Sikhs. The Thirma was an essential part of a Punjabi girl’s wedding trousseau. Its characteristics were red, pink, purple, indigo or green thread stitches on a white khaddar base. In some pieces, large-scale triangles interrupt the long border on opposing sides. Placing of these triangles is significant, for when worn by a bride, the triangle falls over her head, symbolizing the auspicious tilak worn on the forehead. A nineteenth century Thirma from the north-west region of Punjab (Bharany collection) uses the negative spaces between the bright pink threads to expose the off-white fabric it has been embroidered on. This brings out the graphic effect of the pattern. The entire surface of this odhani is decorated with a lozenge structure on finely woven off-white cloth. The darning stitch with silk threads creates a glistening crimson-pink field, which is considered auspicious. At the centre of each lozenge, two motifs depicting the ear of the wheat plant are embroidered with green thread. The wheat ears are reflective not just of an agricultural tradition, but also carry blessings for fecundity and wealth.

No Longer a Labour of Love

- Parvati Maasi, IGNCA, 2013

- Bakshi Rana, IGNCA, 2013

When I heard about the Phulkari exhibition at the IGNCA, I was told that there was also a group of women who had come to demonstrate Phulkari. I was very keen to meet someone doing Phulkari in the contemporary context. And that was how, in the month of April, in 2013, I met Lajwanti, Parvati Maasi, Prito Aunty and Bakshi Rana who had travelled from Punjab to demonstrate Phulkari embroidery. But, when I heard their stories, I realised that they had travelled much farther than that. They had all learned Phulkari out of choice. It was an aspiration, but none of them did this work today for the love of embroidery. They said it was majboori that they had to do it in order to earn, to keep home and hearth alive. There was no passion for the craft. Prito, recounted how she had made her own dowry, yet also spoke of the work she did today as majboori. When I asked what she would do if she had all the money she could ask for, her reply was ironical. She said she would like to buy these fabrics—the Phulkaris that were on sale in the demonstration area—like she had seen us urban women purchase. She was born in Kinnaur village, district Patiala, around 1963. Her parents were poor and did majdoori, mostly making manjees. Her mother also earned doing some embroidery work. Although traditionally this art was practiced mostly as a personal pursuit and not something for profit or sale, it was not uncommon for wealthy families to get others to do it for them, even though they themselves had learned Phulkari work, and that was how Prito became exposed to and learned the art. Prito had embroidered chaddars and dupattas as well as woven punja dhurries to take to her new home. Tinged with sadness, her recollections of this did not carry any of the romance and nostalgia evoked by Dhamija in her recollections.

The Phulkari and Bagh shawls made and worn by the women of Punjab, were enormously popular from 1850-1950 AD. But where did these exquisite embroideries originate from? Not much is known about the beginning of this tradition, but it is thought that the art of Bagh and Phulkari embroidery came into India with the migration of the Jat peoples from Central Asia. According to ancient European historical records and archaeological discoveries, the possible forefathers of the modern Jats were the Scythians, Samaritans and Alans. This tradition of thread decoration, popularised in Punjab, could also have drawn inspiration from Gulkari embroidery of Iran, which also means “floral-work”. The word Phulkari first appeared in Punjabi literature in the eighteenth century and Waris Shah’s historic poem Heer Ranjha describes Heer’s trousseau enlisting items of Phulkari. But there are no surviving pieces from before the 1850s. John Grisham, writing on the shawls of Punjab says there are apparently no references to Bagh or Phulkari in classical Indian literature, nor are there any surviving pieces from before the 1850s.

Chandrama Bagh and Wari-da-Bagh

- Chandrama Bagh

- Detail of Chandrama Bagha, photo by Gopika Nath

The Chandrama Bagh, or moonlit garden, is one of the most exquisite of Bagh designs and was generally worked on an indigo dyed background, with a lustrous white silken thread creating the silvery surface of the moon. The Chandrama Bagh, we are told, was a treasured family heirloom. In a nineteenth century odhani from Punjab, the varying directional movements of the stitches create a rich lustrous effect bringing to mind the luminous glow of a full moon. Closer examination of the lozenges creates a rich variation of the sacred grid.

In the midst of this large expanse of a glowing white, a solitary, dark motif draws the viewer’s attention. Is it for nazar—a protection from the evil eye? Or is it the eclipse of the moon? While I like the idea of the latter, it is most likely that the dark motif was intended to ward off evil, more so since the Baghs were embroidered by women for their wedding trousseau or by the older women of the family for their daughters and granddaughters, to be gifted at their weddings. This odhani, from the Bharnay collection shown in the Sacred Grid exhibition, is finished with a four sided border in the rich colours of gold, representative of Surya or the sun with occasional hints of pinkish-red, indigo blue and a dull shade of pale, greenish-gold. Although referred to as the Chandrama Bagh, the white luminescence of the moon, offset by the colours of the sun, presents a subtle canvas of night giving into day or vice versa. Either way, for the woman who conceived and embroidered this, even the dark night is apparently filled with light.

As one entered the Sacred Grid exhibition, the wall immediately in view, in front, was covered in its entire width and length with three gorgeous Baghs measuring approximately 48 x 96 inches (122 x 244cm) each. In the centre was an exquisite Wari-da-Bagh. Every inch of the base fabric was covered in rich golden-yellow silk evoking Surya, the sun, and its invigorating, life-restorative force. The Wari-da-Bagh, as the legend goes, was begun the moment a male child was born, to be given to his bride as she entered her marital home. Traditionally, the young bride was wrapped in this powerful fabric embroidered with prayers, dreams and good wishes, by the groom’s grandmother. The golden Bagh often has a smattering of red and blue-black which signifies the presence of the tri-gun or three elements that form an essential part of our being. Satvik is usually presented as yellow for joy, harmony and meditation; red is representative of rajas evoking the powerful and passionate, with blue-black alluding to tamas which is seen as turgid, deep and all enveloping. Dhamija tells us that a Wari-da-Bagh can also narrate the family history, where yellow would also signify a harmonious family. She says that through colour variations in the embroidery changes in family life were indicated, where a moment of joy was implied by the use of red and an embroidered passage in blue-black could reflect a sense of loss.

As I stood looking at the Wari-da-Bagh and pondered on the romantic notions that surround much of Phulkari lore, I could not help but think of Bakshi Rana, one of the artists from Tripri. A refugee of Partition, at the age of nine years, she had begun doing Phulkari embroidery when she was about fifteen years of age. Watching others—ik umang jaag uthi— a desire came into being and she thought she would like to do it too – make some for her own dowry perhaps. Around the same time, she was married off to her dead sister’s husband, her brother-in-law, and widowed five years later at the age of twenty. This marriage had been arranged to take care of her sister’s children who otherwise may have had to deal with a step-mother who may not have cared about them. Of all the four women I met at IGNCA, Bakshi Rana seemed the saddest and wore a really haunted look. Her sister had four or five children whom she brought up as her own. As I listened, I couldn’t help thinking, what a life! There was this fifteen-year-old with that faint desire in her heart to do some colourful embroidery work, reflecting upon and expressing her young hearts dreams and desires, when her sister dies and the responsibility of her sibling’s family falls on her young shoulders. She doesn’t have the luxury of choosing her spouse or the pleasure of bearing her own children, so where then lies the possibility for expressing desires and aspirations? The mind possibly shuts down all its imaginative faculties when faced with such circumstance.

Partition and Phulkari

When I consider the stories of these women, the hardships they had born, it is no wonder then, that umang turned into majboori, where the Bagh and Phulkari work of dreams and aspirations gave way to the relatively lacklustre work done today. It makes me wonder whether things would have been different if Partition had not happened. If life had not been disrupted through the rather traumatic displacement of Partition and these women had stayed on in their villages in Pakistan. Would they have had different stories to recount? Would the history of Phulkari have read differently?

My father’s family were from the fortress town of Multan, but in my family, Partition and life in what is now Pakistan has not been spoken of much. However, through a lot of probing I did manage to unearth some rather distressing experiences faced by two of my father’s four brothers. The youngest recalled his journey as a teenager of seventeen years, travelling by train alone, from Multan to Lahore, where the single most important thing had been to find a safe place to hide, inside trunks or some such, during the night, fearing for his life. The mood was savage and each night people were massacred on the trains that were crossing over to India and Pakistan. Another, older brother, an officer in the Indian army, travelled by bus to meet other family members travelling from Pakistan, and counted eighteen to twenty dead bodies for every mile, from Ambala to Amristar—Muslims slain by Hindus and Sikhs. He recounted one Sikh waving a bloodied sword, shouting out loud, “chuha nussriya si, maar ditta” (“That scuttling mouse, I killed him!”)

Urvashi Butalia in her research interviews, published in The Other Side of Silence, has also recorded brutal atrocities that came to pass where daughters and mothers were drowned or burned alive, ostensibly to protect them. And one has heard and read other records of violence perpetrated at the time, but, to hear it from family members, who saw and survived it, sent shivers down my spine. While recalling her experience of Partition, one of the elderly embroiderers, Parvati, started singing: “Bande teri zindagi Waghe nadiya da paani, chaar din di bahar, ho hoshiyaar bandeya, nahin toh royega zaro zaar bandeya” voicing profound wisdom, reminding herself, and all of us, that our lives are like the waters of the river Wagah, whose precious days of bliss may flow without us realising it. So, be present and enjoy each day for whatever it brings, otherwise we may shed tears in regret for the rest of our lives, for this might be the best we get. In this, she reiterates the ideas propounded by Coomaraswamy that philosophy, in the Indian realm of thought, “is the key to the map of life”. Where it is not merely an intellectual pursuit, but it is regarded with deep conviction that through this lies freedom from ignorance or avidya, which masks the reality of being, towards salvation or moksha.

Phulkari has been one of the biggest losses of Partition, in terms of a cultural practice and heritage which went into decline and near oblivion after the devastating fall-out of independence in 1947. An art that was cultivated primarily to create the trousseau and dowry of young girls, who mostly embroidered the shawls and chaddars themselves, the traumatic events before and after Partition cannot have been conducive to flower-work that celebrated life and its cherished dreams, when so much unnatural death and heart-searing devastation had been seen in the region. The Punjabi community is renowned for its get up and go attitude—of not letting the past affect them. But in the realm of this embroidery, it seems that the past has played a significant role in not continuing this vibrant tradition. Where so many daughters were drowned and burnt alive, it is possible that the women questioned the merit of the nazar and prayers that were sewed into these shawls, gifted to young brides.

But, there have been pockets where Phulkari and Bagh embroideries were carried on, albeit in a more professional and commercial way. Paradoxically, this also contributed to the decline from the kind of excellence seen in the older pieces. Work done for annas and paise rather than with the excitement and anticipation of embroidering your own garden of dreams, had to incorporate a detached engagement resulting in less soulfully embroidered fabrics. Unlike block printing, weaving and other textile arts, embroidery work such as Phulkari is heavily invested with the passion and presence of the person handling the needle and thread.

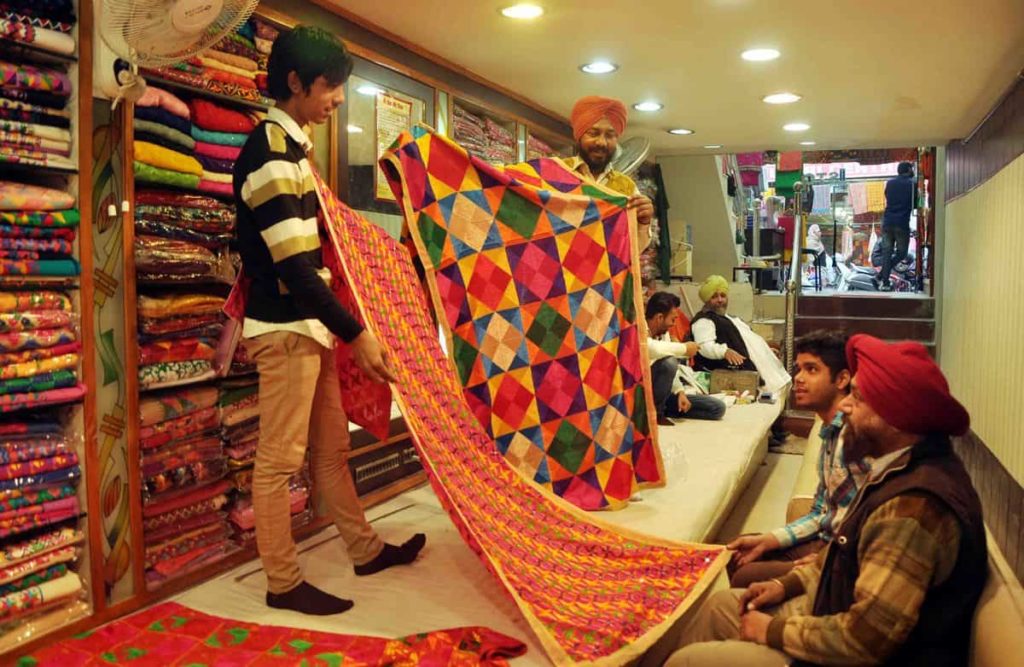

Phulkari Today

- Adalat Bazaar, a market view, photo courtesy of 1469

- Phulkari on cotton fabric with rayon thread, Adalat Bazaar, 2015

- Adelat Bazaar, inside a shop, photo courtesy of 1469

- Phulkari on cotton fabric with rayon thread, detail, Adelat Bazaar, 2015

The embroidered chaddars and shawls that were produced in the nineteenth and early twentieth century are not part of the contemporary pieces we see in the market-place today. While drawing from this rich tradition in terms of stitch vocabulary, they have expanded the colour palette to include a wide range of much brighter hues. The base fabric and thread too have changed from the earlier robust khadi to translucent georgettes and polyester-silks with rayon thread replacing the mulberry-silk threads used earlier. The motifs, however, are more judiciously placed, so the ground fabric gains greater significance. The darning stitch is used with the Holbein stitch of the earlier Chopes, but not to cover the entire fabric as a young girl’s garden of dreams, but as fillers for motifs sparingly placed on the fabric. The resultant effect, with an unlimited colour palette and meagre stitch-work is gaudy, and lacks the over-all sophistication of the earlier work.

During my visit to the Sangrur District, on the way back to Delhi, we made a brief stop in Patiala, where I bought a couple of Phulkari stoles at the renowned, bustling market of Adalat Bazaar. This market is located in what was once the Qila Mubarak complex, built in 1763 by Ala Singh, founder of the Patiala dynasty. At one time, this fort also housed the royal family of Patiala. This bazaar has lanes filled with shops that sell the cheaper Phulkaris. The main gate of the Mubarak fort is all but lost in the hustle-bustle of the popular bazaar, where vibrant, multi-coloured, diaphanous embroidered dupattas flutter in the breeze, hanging alongside other brightly coloured wares. And shopkeepers stand outside their stores to tempt custom, chanting fervent eulogies about quality of their product. 1469, a small chain of stores run by Harinder Singh and his wife Kiran, specialises in all things Punjabi. In their effort to re-create some of the lost glory of Bagh embroideries, they work closely with Building Bridges India, in Sangrur, to make small key chains in the tradition of the Baghs of yore. The girls at this centre are unable to do much more than two to three inches of this fine work. And unlike the women in history, who worked from the back, counting the warp and weft threads, these young girls have the design printed for them and there is no need for them to count the thread or work from the back of the fabric.

March 2015, my attempt at Phulkari, counting the threads, but working from the front, photo by Gopika Nath

On my return from Balran, I was keen to try my hand at Phulkari work in the traditional way, working from the back and counting the warp and weft thread. I procured some dark coloured casement where the gap between the warp and weft were significant enough to count and insert a threaded needle. I was determined to do this and struggled for over an hour without actually managing to do much. The diagonal stitch was impossible but,finally, I did manage a small horizontal band, with vertical upright stitches of about one-inch-long and across four threads vertically. It was an achievement, even though I could not work from the back. This little experiment has remained at that level, because I realised just how much commitment was required to learn the art. It also heightened my understanding of the enormous skill and passion that the women of yesteryear Punjab had imbued this craft with. The loss, in the kind of skilled work once done, is poignant because it is not just the loss of an excellence in a craft, but of a practice that imbues life itself with much grace.

- Raman and Kiran with their chaperon hovering close, 2015

- Rman copying from an old Phulkari, IIC, New Delhi, 2015, photo by Gopika Nath

- Neesha at the Balran Centre, doing Bagh Phulkari, photo by Gopika Nath

Established in 2003, the Nabha Foundation in Nabha, district Patiala, is also working to develop the finer nuances of Bagh embroidery, where the girls have been taught by one of the few women in the region who knew the art and had learnt it from her mother. The foundation claims to have trained over eight hundred women, teaching skills, techniques, colour combinations, traditional motifs and designs and knowledge of Phulkari, to be used in the production of traditional yet contemporary products. Raman and Kiran were two girls, from the Nabha Foundation, that I met in Delhi in 2015. They had travelled from Patiala for a demonstration in conjunction with yet another exhibition of Phulkaris at the India International Centre. It was interesting to see that they were able to work using the counted thread principle devised by Punjabi women generations ago, which as discovered through my attempt was an exceedingly difficult art. But they were doing it rather effortlessly. They were shy and hardly spoke and were especially restrained by their chaperone who had been instructed they not reveal much information. Nabha Phulkari has purportedly secured good custom from high end customers and boutiques and their production is based on a small work-force, which they covet zealously. I found Raman to be exceptionally skilled. She was adept at looking at a motif from an old piece and without drawing the motif, but just looking at it, was able to recreate the same pattern on the fabric before her. Unlike the traditional embroiderers, they did use an embroidery hoop and the fabric they embellished was of a finer count than the traditional khaddar or khessi, and was mill-made.

One of the older women from Tripri, at the IGNCA Phulkari demonstration in 2013, migrated with her family from Pakistan in 1948, when she was six years old. Parvati and her family were given government quarters in Patiala. Her mother worked in people’s homes, washing clothes and dishes, and Parvati would accompany her. In the evenings, she recounts how they used to embroider things for themselves and one evening a Rajasthani baniya passed by their galli, saw them working and asked them to make some pieces for him. The designs were left to them, to draw upon an inherited repertoire, but he gave them the chaddar, golle’ and Anchor-wale lacche. “Usse hum hoshiyar ho gaye, kaam karne lag gaye” (“We became wise to the profitability and started working freelance, earning five to twenty-five paisa per motif, making one to two rupees a day”.)

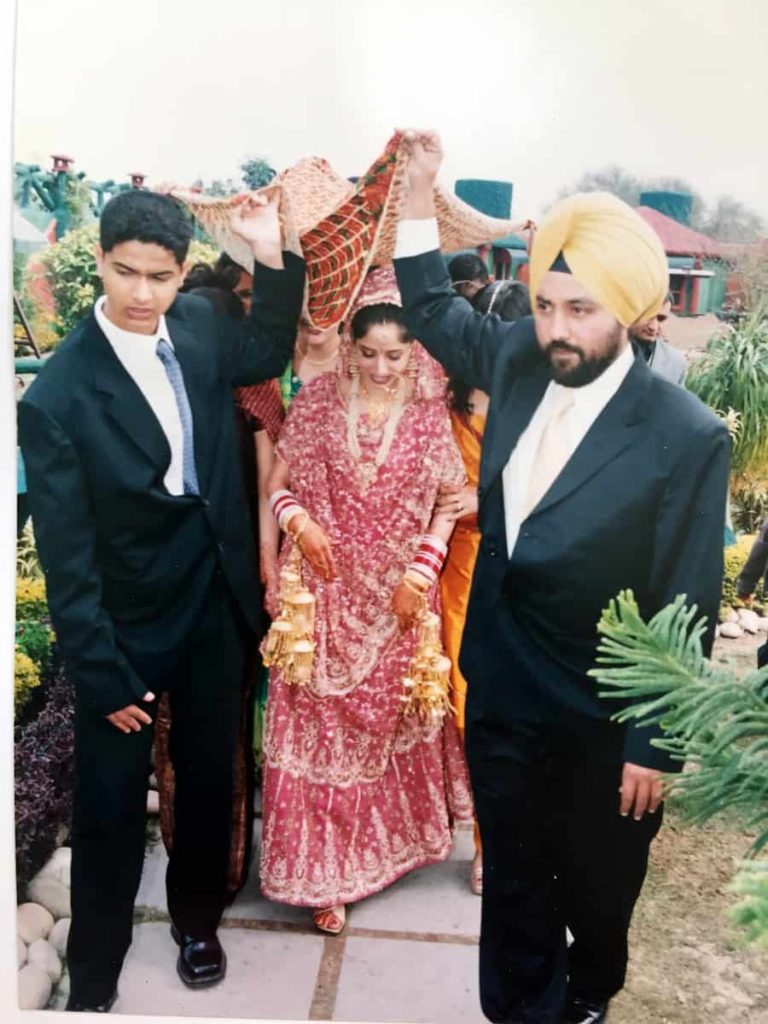

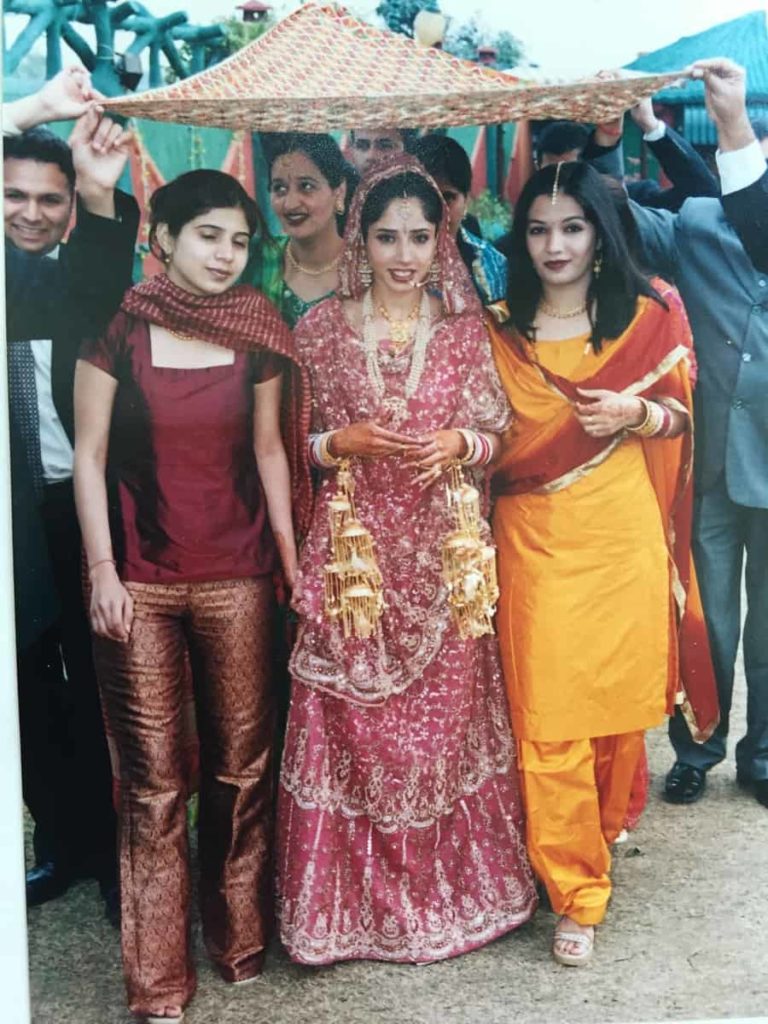

The Parvati that I met was obese; she was old with failing eyesight and diabetic but full of stories. Most of Parvati’s family used to spin thread—Gandhi wala charkha. Her mother, Naani and Parvati did spinning, more than embroidery, even though they did embroidery for a living: “mn badde chakkar khaunda hai, Na khushi na dukhi – velli nahin baith sakdi hu, mn bahut khush haunda hai, kadhai karde karde”. The mind, she says, goes round and around where she feels neither happy nor sad, but cannot sit idle. When she embroiders her mind is at peace. This sense of equanimity that envelopes one while doing embroidery, is something that I and most contemporary stitchers would be familiar with. This meditative aspect of the art has possibly been an important factor in enabling women like her to continue doing it, despite being paid a pittance for the work. Both Raman and Kiran, from the Nabha Foundation, also articulated the same sentiment that they liked doing the embroidery—“achha lagta ha”! I probed for some deeper insights, but they were unable to articulate any more than this. In the midst of what has clearly been a huge loss—of a tradition and skill—the individuals and foundations working to revive the art, form a silver lining. In addition, some Punjabi families continue with the tradition of Phulkari as part of rituals surrounding the wedding ceremony. Aiana, a young Sikh friend of mine, recounted that during her wedding in 2004, when she was being escorted to the wedding mandap, her brothers held the four corners of a modern-day Phulkari over her head. The fabric used was not the richly crafted fabric that one has seen through exhibitions like the Sacred Grid and A Passionate Eye. The embroidery was done on light chiffon or georgette. Indeed, most of the Phulkari embroidery done today is crafted on similar, lighter and diaphanous materials, but it’s reassuring to note that the usage is not entirely lost to time or the fickleness of fashion trends.

- Aiana during her wedding when her brothers escorted her to the wedding mandap.

In 2015, Harinder Singh of 1469, whose passion for the revival of Punjabiyat is invigorating, invited me for an exhibition of paintings at India Habitat Centre, Delhi, by a Sikh surgeon settled in the US. As part of this exhibition, the artist, Mr. Shivdev Singh, had published a book reflecting on the culture of Punjab. He writes of visits to his ancestral village in the Bhatinda district of Punjab where five generations of his family have lived, and recalls the local village pond or toba where the community meets and closeness of the village community, where everyone seemed related because of the shared culture that brought them close together. The book is a tribute to his roots and the culture of a Punjab that younger generations may never have seen, nor are likely to. Like Mr. Shivdev Singh, second and third generation Punjabis, children of families who were once refugees on the Indian side of a now-divided Punjab, are also finding their feet in contemporary society, beyond the village pond. Some like Shivdev Singh, Aiana Dhillon-Jain, Harinder and his wife Kiran, aspire to recapture the traditions of their forefathers in small ways in their contemporary lives. Through them the Phulkari tradition may well see a revival, even if, as referred to in this folk song, the bride or her groom’s mother does not embroider this garden of dreams and prayers herself.

Ih phulkari meri maan ne kadhi,

My dear mother has embroidered this Phulkari

iss noo ghut ghut jhaphiyan paawan

I embrace it again and again with affection

It may well have been the beleaguered women of Tripri and others like them, with their love for the craft they saw growing up, that have kept alive the skill. But it is the young girls who are being trained in Sangrur and Nabha and other such Centres, who enable a possible revival—reclaiming the lost embroidered gardens of Punjab.

As a textile-artist who has espoused the role of artist-craftsperson to bring attention to the nuances of hand-crafting, as practiced in ancient India, through my embroidery work, I have found much to inspire me from the embroiderers that I have met and the changes in the way Phulkari is now done. While change is inevitable, what I would like to see is the emergence of the practitioner’s personal investment in the doing of this embroidery, where the work is invested with qualities of workmanship that elevate mere skill to an art. I see this as a vital component in the practice of Phulkari embroidery, towards sustaining the continuation of the craft. Whether this comes from increased clientele and value accorded for the work which inspires greater personal engagement in the making, or if it comes from educated urban artists, such as me, using the stitch in their own embroidery practices, elevating the craft’s value by bringing it into the hallowed white cube of the fine art space, it is difficult to say. But, I have made an attempt to learn this, however feeble, which I hope to continue learning and incorporating into my art, to lend my voice to support the revival of a precious legacy.

GLOSSARY

Annas – Currency unit formerly used in India and Pakistan, equal to 1/16 rupee. It was subdivided into 4 paise .There were 64 paise in a rupee. The term belonged to the Muslim monetary system. The anna was demonetised as a currency unit when India decimalised its currency in 1957.

Bagh – Garden

Bavan Bagh – Bavan means fifty-two. The Bavan Bagh would have 52 sections with different patterns.. The Bavan Bagh is rare as only a few women were able to design this. The field is subdivided into 42 or 48 rectangles, each containing a different multicoloured motif. The remaining four or ten motifs are placed in the side or end borders.

Chaddar – Wrap measuring 48 x 96 inches (122 x 244cm) approx

Chandrama Bagh – Moonlit garden Charkha – Spinning wheel used by Mahatma Gandhi

Chope – The Chope – a Phulkari variation, with its double sided architectonic pattern has the motif of the temple along with the peacock, which is associated with marital love, longing and desire. It is also associated with the rainy season when the peacock calls out to the dark clouds to descend to the earth and fertilize it. – Jasleen Dhamija, Sacred Grid exhibition catalogue. It is also said that this Bagh was given to bride by her grandmother.

Chopat – Game of dice

Chowk – A courtyard or junction where four pathways meet

Darshan Dwar – Darshan dwars recreate the multiple doorways that lead to the shrines of the local Pirs as well as the temples and Gurudwaras famous for wish fulfilment. Women embroider their life and pour out their longings, asking for blessings. The embroidery is offered to the shrine when their wishes are fulfilled – Dhamija

Dhurrie – Hand-woven floor covering

Dibiyo-wala- bagh – This Bagh features a combination of chowk and the sacred grid. The yellow and white is emphasized by the introduction of the smaller red and black boxes. The border has the powerful panchranga scheme [five colours] with a leheriya [wave]pattern and the damru, the drum associated with Shiva.

Dupattas – Veil/ wrap/ scarf

Galli – Lane

Ghungat – Veil or is worn over the head, wrapping the shoulders and head falling over the forehead, so that the face is not seen.

Golle – Round Balls [of thread]

Gurbani – Word of the Sikh gurus, usually sung

Gurudwara – Temple or place of worship of Sikh Community

Heer and Ranjha – One of several popular tragic romances of Punjab. There are several poetic narrations of the story, the most famous being ‘Heer’ by Waris Shah written in 1766. It tells the story of the love of Heer and her lover Ranjha. The story of Heer and Ranjha is said to have had a happy ending but Waris Shah gave it the tragic end, thus elevating it to the legendary status it enjoys. Waris Shah also suggests that the story of Heer and Ranjha has deeper connotations, beyond the obvious love of a man for a woman, and that it signifies man’s eternal quest for God.

Lacche – Skeins of embroidery thread

Kadhai – Embroidery

Khadi – Cotton, hand-spun fabric woven on a pit loom, in a plain weave

Khaddar – A coarse, cotton fabric woven on a pit loom, in a plain weave

Maasi – Means mother’s sister but can also be used to refer to someone with respect, by calling her an aunt.

Majboori – Necessity/compulsion

Majdoori – Daily wage labour

Manjees – Beds made from rope – usually Jute

Naani – Maternal grandmother

Nakshatra’s – [Sanskrti] is the term for ‘lunar mansion’ [through which the moon moves in its orbit around the earth], in Hindu astrology. A nakshatra is one of 27 (sometimes also 28) sectors along the ecliptic- path of the sun. Their names are related to the most prominent asterisms or pattern of stars in the respective sectors.

Navratras – The beginning of spring and the beginning of autumn are considered important junctions of climatic and solar influences. These two periods are taken as sacred opportunities for the worship of the Goddess Durga. The dates of the festival are determined according to the lunar calendar during these nine nights and ten days, nine forms of Devi are worshipped.

Nazar – Evil Eye

Odhani – Wrap/ Dupatta

Paise – Pennies, 100 paise make one rupee

Pat – Un-spun, reeled silken thread

Pind – Hometown or village

Peeche – Behind

Pothwari – A dialect of Punjabi spoken widely by the population of the Potohar Plateau in Northern Pakistan.

Punja – Richly patterned Dhurries [rugs] where a tool, which draws it design from the five fingers of the hand, is used to push the weft thread down.

Rajas – [Sanskrit] In Vedic philosophy there are three gunas or attributes of which rajas stands for excitable. No value judgement is implied as all guna are indivisible and mutually qualifying.

Rajasthani baniya – Trader from Rajasthan

Sassi and Punnu – is a famous and tragic folktale of love told across the length and breadth of Sindh and Punjab. Sindh is one of the four provinces in Pakistan. On the northern side it borders Punjab. The story is about a woman ready to undergo all the troubles that would come her way while seeking to find her fiancé, Punnu, from whom she is separated by his jealous brother. Sassi endures a difficult and unfulfilled journey through rough terrain of a dessert and a hazardous river. Like the Phoenix, Sassi was engulfed by flames and all that remained was a heap of her ashes.

Satvik – [Sanskrit] In Vedic philosophy there are three gunas or attributes of which sattva or satvik stands for purity and is the most rarefied of the three gunas. No value judgement is implied as all guna are indivisible and mutually qualifying.

Tamas – [Sanskrit] In Vedic philosophy there are three gunas or attributes of which tamas implies indifferent, indifferent, lower energies. No value judgement is implied as all guna are indivisible and mutually qualifying.

Tehsil – District

Tilak – Mark worn on the forehead and is created by the application of powder or paste. This may be worn on a daily basis or for special religious occasions, such as the marriage ceremony.

Umang – Hope

Vahana – Vehicle associated with various Hindu Gods, usually in animal form

Wagah – Is a Village in Punjab on the border of India and Pakistan, through which the Wagah River runs.

Wari-da-Bagh – In West Punjab, following the birth of a boy, on a day appointed by the family astrologer, it was customary, to begin a Wari da bagh in amidst singing, dancing. Sweetmeats and red yarn would be distributed and the newborn’s, paternal grandmother would embroider the first stitch. This Bagh would be gifted to the boy’s bride when she entered her marital home. Worked in yellow/gold yarn on a red ground, the colours symbolised luck and fertility. The whole surface is covered with lozenges or diamond sections, each enclosing a smaller one. In especially elaborate pieces three different sizes of concentric diamonds/lozenges are found, the smallest was again divided into quarters. The sides and ends usually show various patterns worked in several colours. To produce such a Bagh could take over a year. Regarded as family heirlooms and they may be worn briefly as an act of remembrance.

FURTHER READING

Butalia, Urvashi. The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2000.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish. The Dance of Siva: Essays on Indian Art and Culture. Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications, 1985.

———. The Indian Craftsman. Probsthain & Co., 1909.

Dhamija, Jasleen. Asian Embroidery. Abhinav Publications & Crafts Council of India, 2004.

———. The Sacred Grid. New Delhi: Gallery Art Motif, n.d. Krishna, Lal. Phulkari: From the Realm of Women’s Creativity. 2013 edition. New Delhi: Aryan Books, 2013.

Singh, Shivdev. Beyond the Village Pond: Reflections on the Culture of Punjab. Speaking Tiger Books, 2015.

Tillotson, Giles, ed. A Passionate Eye: Textiles, Paintings and Sculptures from the Bharany Collections. Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2014.

Tyabji, Laila. ed. Threads & Voices: Behind the Indian Textile Tradition. Published for Marg Publications, 2007.

Author

For Gopika Nath, thread is a metaphor for living. A Fulbright Scholar and alumnus of Central St. Martins School of Art and Design [UK], Gopika Nath is also an art critic, blogger, poet and teacher who lives and works in Gurgaon, India. Passionate about textiles, she is evolving a contemporary language of thread, through the art of embroidery.

For Gopika Nath, thread is a metaphor for living. A Fulbright Scholar and alumnus of Central St. Martins School of Art and Design [UK], Gopika Nath is also an art critic, blogger, poet and teacher who lives and works in Gurgaon, India. Passionate about textiles, she is evolving a contemporary language of thread, through the art of embroidery.

Comments

I love all kinds of embroideries !

I love phulkari !

This is obviously a labour of love. Like embroidery itself, much detail has gone into this essay along with research into an entire tradition. Really well done! I love how the various stories of people and the different types of Phulkari and Bagh are all weaved into one narrative, also that she has taken efforts to connect the past and present of the craft with the people who make it. It’s interesting to see through pictures the contemporary use of the craft, giving the reader an all encompassing insight into Phulkari. Albeit with sad and happy feelings about Phulkari today. Thus, by linking the essence and evolution of the craft in context with its creators, the author has very effectively garlanded ‘The stories behind what we make.’

I have seen this embroidery on dresses but have no idea to do it . I would like to view it.

Go pika, what a rich display of emotion through all your writings, I feel I am in the garden with you.

We found this image of a Phulkari used to adorn a wedding car: https://thebigdaytales.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/wedding-33.jpg?w=650

Very good information for all