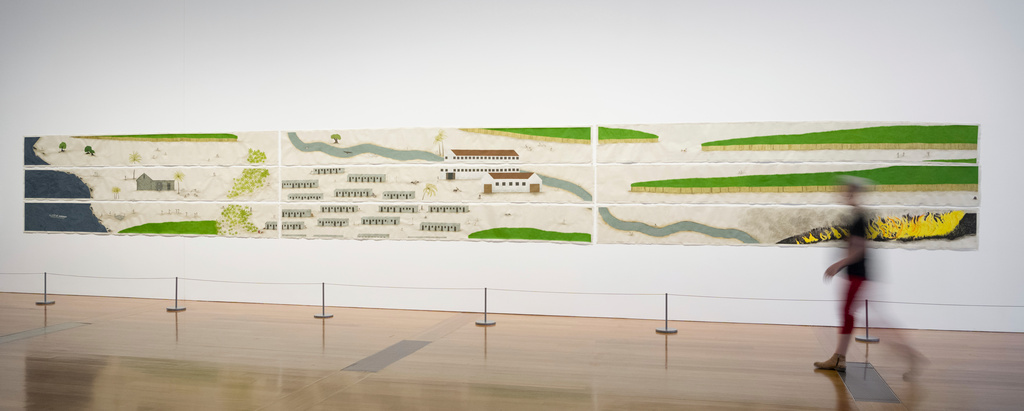

- Sancintya Mohini Simpson, “Natal #1-4”, 2018, watercolour and gouache on handmade wasli paper, Museum of Brisbane Collection, photo: Louis Lim.

- Sancintya Mohini Simpson, “Natal #1-4”, 2018, watercolour and gouache on handmade wasli paper, Museum of Brisbane Collection, photo: Louis Lim.

- Sancintya Mohini Simpson, “Natal #1-4”, 2018, watercolour and gouache on handmade wasli paper, Museum of Brisbane Collection, photo: Louis Lim.

- Sancintya Mohini Simpson, “Natal #1-4”, 2018, watercolour and gouache on handmade wasli paper, Museum of Brisbane Collection, photo: Louis Lim.

Elena Dias-Jayasinha learns about an artist who honours a matrilineal history of struggle as displaced, indentured labourers.

It’s been a big year for Sancintya Mohini Simpson. Over the past 12 months, the Meeanjin-based artist has been busy preparing for a variety of exhibitions, both local and international, including the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT11) at Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA). For more than three decades, the Asia Pacific Triennial has brought together leading practitioners throughout the Asia Pacific region. This edition of the Triennial is bigger than ever, featuring 70 artists, collectives and projects from more than 30 countries.

Sancintya’s work in APT11 continues her investigation into her matrilineal history and themes of migration, memory and trauma. A descendant of indentured labourers sent from India to work on sugar plantations in South Africa, Sancintya uses her work to address gaps and silences in the colonial record and, through counter-narratives and speculation, create space for healing. All her work – whether painting, poetry, performance, video or installation – is rooted in archival research surrounding her family history and wider narratives of indenture. Interested to learn more about her practice, I reached out to Sancintya over email, and she generously offered to meet.

Initially, we’d planned to meet at Sancintya’s studio. Flooding caused by Cyclone Alfred, however, led to a change of plans, and we meet at QAGOMA, catching up over coffee before visiting her work in APT11. Sancintya is buzzing, having made a breakthrough in her research the night before. Scrolling through microfilms digitised by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, she’d found the marriage register of her great-grandparents. This one document held details she never thought she’d know about her great-grandmother and great-grandfather, making her one step closer to constructing a full family history. “There’s just no words for it,” she shares, “I never thought I’d be able to find all this out”. As we sip our coffee, we talk about where her research began.

- Sancintya Mohini Simpson, “Mother and I”, 2012-14, archival pigment print, gouache, watercolour and liquid gold, courtesy the artist.

- Sancintya Mohini Simpson, “Mother and I”, 2012-14, archival pigment print, gouache, watercolour and liquid gold, courtesy the artist.

Sancintya grew up in the Northern Rivers, a region in New South Wales known for sugarcane farming. Living near so many sugarcane fields, she became acquainted with what she describes as the ‘plantation landscape’ from a young age. She’d always been interested in visual art and literature, and after high school, decided to pursue a Bachelor of Photography at Queensland College of Art. Initially, Sancintya’s goal was to study and find work. As she moved through her degree, however, she attended classes in art theory, many taught by Maura Reilly, and connected with like-minded students, including D Harding. These relationships opened her eyes to the ‘art world’ – she finally saw it as a space in which she could exist and one full of possibilities.

From the very start, Sancintya saw her practice as a means of understanding her life. She shared that, although some of her early explorations felt forced, things changed when her mother registered as an Overseas Citizen of India and needed to prove her Indian ancestry. The family received a ship list documenting their ancestors who had been taken from Madras (now Chennai) by the British Empire to work as indentured labourers in Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal). Receiving the ship list sparked Sancintya’s interest in unpacking her family’s past. In 2012, after finishing her degree, she accompanied her mother on a trip to India. Although her mother went every year, Sancintya had only been once before. The two of them spent a week visiting the villages where their ancestors had lived. “The trip was hard,” she reflects, “but it was also really amazing to see those places”.

A year later, Sancintya returned to India to learn miniature painting. She spent a month in Jaipur, studying under master painter Ajay Sharma. Using the techniques she’d learned, she painted over the photographs she’d taken on her trip with her mother, creating Mother and I 2012-14. This series, navigating inheritance and representation, marked the start of a shift in her practice.

In 2017, Sancintya began making work that directly acknowledged her family’s history and wider narratives of indenture. These include landscape paintings sharing the stories of indentured women. Delicately rendered, the works are littered with scenes of colonial exploitation, but also intimacy and care. Although they are largely speculative, the works draw on years of historical research.

Over the past ten years, Sancintya has built an archive of books, postcards and photographs. Many of the objects are colonial propaganda and misrepresent the realities of indenture. “These objects hold a place, but it’s complex,” Sancintya shares, “because they weren’t made for us and are complicit in our misrepresentation”. In turn, she takes great care thinking through the influence of these sources on her work. Sancintya paints on sheets of untrimmed wasli paper, often installing them in grids to create one continuous scene. Her compositions are purposefully sparse, acknowledging that there are, and always will be, gaps in our understandings of these overlooked histories.

Through her paintings, Sancintya inverts the tradition to focus on lower-caste women of darker skin working in harsh conditions.

The impressive level of detail in Sancintya’s work reflects her background in Indian miniature painting. She explains that she uses squirrel head brushes to achieve such fine lines, but also clarifies: “I’m not painting in the exact miniature style, I’m making it my own”. Historically, miniature painting was used to depict the wealthy and privileged. Through her paintings, Sancintya inverts the tradition to focus on lower-caste women of darker skin working in harsh conditions.

At this point, we finish our coffees and head upstairs to APT11. It’s impossible to miss Sancintya’s work. kūlī / khulā 2024 comprises nine long sheets of wasli paper, referencing scroll painting, another significant South Asian tradition. In the past, artists would carry scroll paintings from village to village, unrolling them and augmenting the stories they told through singing. Unlike miniature painting, scroll painting depicted stories of and for everyday people. By referencing the genre, Sancintya questions which stories come to be added to the historical record and why.

Sancintya Mohini Simpson, “kūlī / khulā”, 2024, installation view ‘The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ 2024, watercolour and gouache on wasli paper backed onto cotton fabric, purchased 2024 with funds from Tim Fairfax AC through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation, collection: QAGOMA, © Sancintya Mohini Simpson, photo: C Callistemon, QAGOMA.

As I take in her work, Sancintya explains it’s not entirely speculative. “I usually don’t tell specific stories in my work except for this one,” she says, “because it’s about the endings and beginnings of the indenture system, and there were some stories that were very crucial to include”. These include the story of Kunti, a young woman indentured on a Fiji plantation. One day, Kunti was sent to weed an isolated banana field, where the overseer tried to sexually assault her. To escape, she jumped into the river and was eventually saved by Jaidev, a boy on a nearby dinghy. Kunti’s story was picked up by the Indian media and used to campaign against indenture. Naraini’s story was similarly used to agitate for change. Naraini was indentured on a Fiji plantation when she gave birth to a baby who died. Refusing to return to work only a few days after losing her child, Naraini was brutally beaten by the overseer and left to walk to the hospital. She suffered brain damage for the rest of her life.

These stories feature alongside historical references, including Aapravasi Ghat in Mauritius, a depot in one of the first British colonies to process indentured labourers; the Barracks Compound in Natal, where the Tongaat Hulett sugar company dislocated local communities to import labourers; and the SS Ganges, a steamship that transported labourers to the colonies until the final years of the system.

In and around these vignettes, Sancintya points out that there are snakes everywhere. She explains that the reptiles carry multiple meanings – some consider them auspicious, while others think them dangerous or evil. The snakes embody contradiction and ambiguity, and within the context of her work, remind us that nothing should be taken at face value, nor flattened for convenience.

Sancintya’s work is rife with scenes of violence and intimacy, repression and resistance, destruction and renewal. There is no one static reading of her painting, just as there is no one static reading of history. What makes her work so powerful is that it gives voice to those who have been silenced from the record, and encourages us to lean into complexity with compassion and care.

Feeling grateful to have heard from Sancintya directly, I thank her, and we begin to part ways. Before we go, however, I ask her one last question: how do you feel visiting your work now that it’s on display in the gallery? Sancintya’s reply is simple: “It’s like visiting my ancestors”.

Further Reading

Nagesh, Tarun. “Sancintya Mohini Simpson.” In The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, 2024.

About Elena Dias-Jayasinha

Elena Dias-Jayasinha is a Meanjin-based curator. She has previously worked at The University of Queensland Art Museum and Griffith University. In 2022, she curated the churchie emerging art prize at the Institute of Modern Art. Currently, Elena is Curator at Museum of Brisbane.

Elena Dias-Jayasinha is a Meanjin-based curator. She has previously worked at The University of Queensland Art Museum and Griffith University. In 2022, she curated the churchie emerging art prize at the Institute of Modern Art. Currently, Elena is Curator at Museum of Brisbane.