A new version of the traditional blanket, tsug dul. We have kept its original size. The single panels woven on backstrap loom can be seen, each at around 30cm. The design was simplified using only natural wool colours. This clear aesthetic is more appealing to potential customers, as sales have proven. Kharnakling, 2017. Photo: Catherine A

We have arrived. The air is chilly and the full moon is lighting up the surrounding mountains and softly shining on the tents of the small nomadic community in the Changthang Plateau.

The ever-blowing wind is stroking the tents and prayer flags, which are fluttering in the night. Even though I cannot distinguish them clearly, I can hear goats and sheep in the distance.

It has been almost a year since I was here last. The lambs have become sheep and the yaks are another year older. The animals have grown a thick fleece, which has kept them warm over the winter when the temperatures dropped to -40°C.

I enter one of the yak hair tents and I am welcomed back by Dolma, one of the nomads: ”Ya julley Catrina le, kamzang in a ley? Solja don hey!”

Yes, I am good and it seems like there couldn’t be any better moment to drink butter tea again.

Dolma prepares the typical tea of the Changpa with fresh butter she hand-churned from the milk of one of the female yaks a few days ago. We sit down next to the small oven in the yak hair tent which Angchok, the husband of Dolma wove over a course of two years.

We are exchanging about the last year, the processing of our wool and the creations which have resulted from it. I am wearing the first prototype of the vest and in a very profound way, it connects them with the weavers who once used to be their fellow nomads and have now settled close to the city of Leh, 150 kilometres away.

They are touching the lining of the vest, eri silk from Assam and I tell them about the other part of our team living in the flatlands, more than 3000 kilometres south-east.

While everyone is examining the vest I realise that this is the essence of KAL. Connecting individuals through the creation of a garment.

It seems like this is what they all say; the freedom to be, in the far, in harmony with nature and with a calm and modest heart.

In Changthang in summer, the days start early and I am awoken by Tenzin, who wants to take me grazing with the flock and see if I have become a stronger shepherdess over the year. A heavy blanket is resting on me, woven of yak wool with geometric and irregular designs in bright colours.

It is fascinating to observe how the culture and craft revolve around the animals and is manifesting constantly. In no other place this has been as obvious to me. The textiles are made by the wool and hair of the animals: capes, blankets, carpets, socks, jackets and even the tent in which the nomads live. Their diet is completely dependent on the milk of the sheep, goats and yak. It provides them with the nutrients which are required to survive in such a climate. Even in Buddhist culture, butter holds a great significance: butter lamps are lit every day to banish darkness and nurture inner peace.

”You ask me what will I do with the flock when I am sick? You know Catrina, I am certain that I will not fall sick. Every day, I am trying to treat the animals at my best, and I am respecting my community. Rarely, I accidentally hurt one of my animals while taking wool or throwing stones. It is for this that I am praying in order to diminish the sin.”

We walk up higher in the mountains, Tenzin is running, screaming and whistling, so much force and endurance lies in his voice. I am imagining wintertime here, him running after the flock, day in, day out.

From over one hundred nomadic families in Kharnak twenty years ago, only 18 are left in 2018. Everyone has different reasons for leaving their traditional occupation, but they all lead to the same place: a nomadic settlement close to Leh.

Some days have passed by and I have left Tenzin and his family and the community in Changthang and brought around 100 kilos to the settled nomads, the community of weavers.

”Ya, in winters the snow is too much and it is so difficult to find food to feed the animals.”

”I know I belong there but my husband fell sick and we were forced to leave Changthang and settle here.”

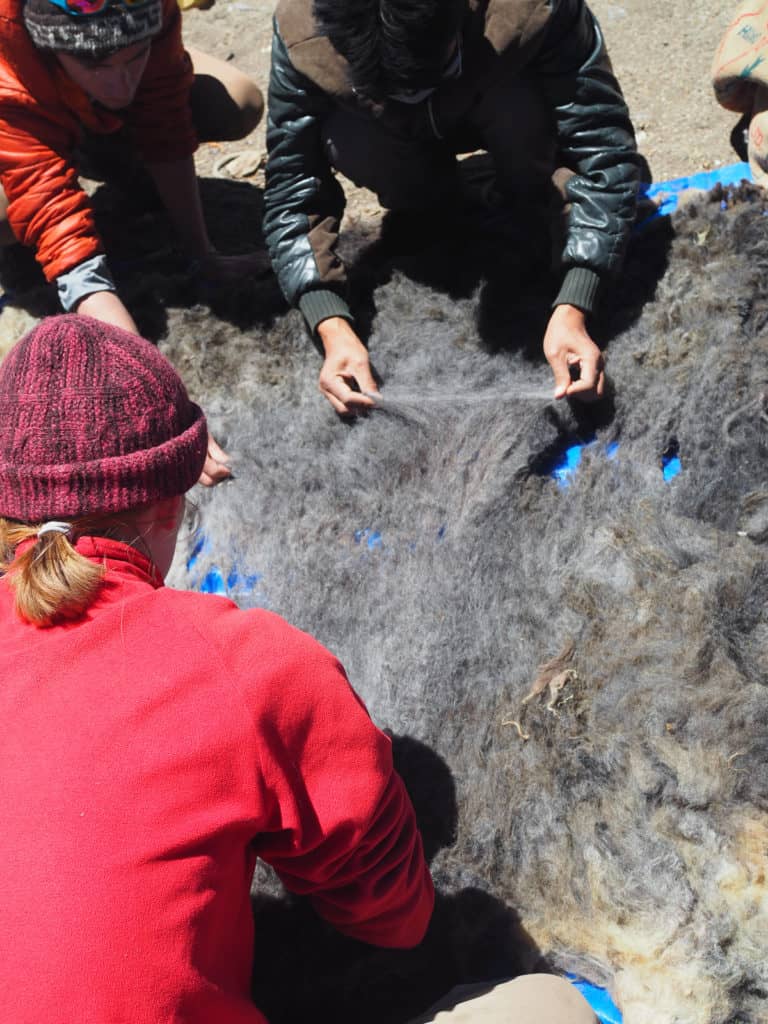

While I am listening to the stories of the weavers Tsering Yangzom and Tashi Yangchen, everyone is taking fleece and yak wool for processing and already starting to spin. ”Our lifestyle has totally changed. We don’t own animals, we have a house and don’t move any longer. However, the weaving is something we are holding on to. It is part of our cultural identity.”

What does it mean to see a craft as part of one’s identity?

It is time and dedication which is manifested in such fabric. I think of my friend Angtak, the brother of Tenzin who once said to me: ”You know when something is good, it will take time.”

- A new version of the tradition blanket, tsug dul. We have kept its original size. The single panels woven on backstrap loom can be seen, each at around 30cm. The design was simplified using only natural wool colors. This clear aesthetic is more appealing to potential customers, as sales has proven. Kharnakling, 2017. Photo: Catherine A

✿

Over the past four years, I have been researching in Ladakh (J&K), Himachal Pradesh and Assam in India. My research has been focused on textile art and the traditional, resource-friendly way of making textiles by hand, using natural fibres from surrounding areas. This research has led to the creation of the social business We Are KAL, referring to kal in Hindi, which means “yesterday” as well as “tomorrow” and epitomizes the approach to carry practices of the past to create a sustainable future.

We Are KAL takes into account all factors in the creation of textiles: social, cultural, economic and ecological. We are reaching customers worldwide and have created a public interest in the origin of a textile, its processes and people.

Our main aim is to reveal the treasures of vanishing cultures to the world, give the deserved recognition with the intention to carry their heritage to the next generation.

In Ladakh, I have worked closely with the pastoral community of Kharnak, living originally on the Changthang Plateau and their traditional textiles made from the wool of their own herding animals. These artefacts range from carpets, woollen fabric to bags. Kharnak has witnessed a steep decline in population from more than 100 families only four decades ago to now, 18 families. Today, the settled community lives in Kharnakling, close to Ladakh’s capital Leh. This location is more than 150 kms far from Kharnak, the land of their ancestors.

Early beginnings of urban migration (until the 1990s)

The Kharnakpa (“belonging to the people” in Tibetan language) is a nomadic community of the Changthang Plateau in Ladakh, bordering Tibet in the East. Their territory lies in the midst of dry mountains, spotted with bits of grass and roots for the animals to eat. It is a very barren landscape where one would not expect thousands of animals to live. However, the Kharnak people have stayed there with their yaks, sheep and goats for centuries.

It seems that the main change occurred in the second half of the twentieth century. In the 1950s, tensions with China eventually led to the Sino-Indian war starting in 1962. This resulted further in the closing of the borders and the territory of the Kharnak. Finally, the entire Changthang region shrunk significantly and trade with Western Tibet ended for good.

The Indian military presence in the region increased drastically and along with it the creation of invisible infrastructure. Roads for military purposes were built as well as garrisons in the entire Changthang region.

As mentioned above, due to the loss of grazing land, competition between the three major nomadic communities of Eastern Ladakh began, which has forced them to schedule the grazing routes throughout the year so that each community could lead their animals to some grass in all seasons.

The following decades saw continuing change in this area. The road was built, bringing Leh and the Kharnakpa closer to the outside world. The barter system had ended and the Kharnakpa had to find alternatives to sourcing the foods they have previously obtained by trade. Cash became the most important trading currency and all efforts went towards obtaining it. Within Ladakh, governmental actions also influenced the way of living in Changthang. In the 1970s the ration scheme was introduced to those having the status of Scheduled Tribe. Since 1989, the Changpa tribe, to which the Kharnakpa belong, is listed as a Scheduled Tribe and therefore receiving the ration (Singh, 1994). It was given rice, flour, sugar, kerosene and other essential items at highly subsidized rates.

Already in those years, the first Kharnakpa left their old life and animals on the Changthang Plateau to settle in the barren land within the Tibetan colony in Choglamsar. This area was given to Tibetan refugees in the 1960s and 1970s. The land not used by the Tibetans was sold at a low price to the new settlers from Kharnak. Within a short span of time, people such as Sangey Palzang, born and brought up in Kharnak, settled early in the 1970s and bought numerous properties in this area. Over the years, the first settled Kharnakpa like Sangey Palzang sold the land to people from Kharnak who decided to settle. Having access to land lowered the threshold of the risk of settling to the Kharnakpa. Steadily, the cash economy and settlement played a role in the life of this community.

The economic pull: The 1990s and 2000s

In the time following the first-movers described above, a big wave of migrants set in, especially in the 1990s and 2000s.

Once the first nomads had settled in Kharnakling near Leh, the pastoral community in Kharnak grew curious about life in the town. Of course, to many Kharnakpa who have endured much hardship in their lives, to have a house and access to basic facilities has given them relief. Moreover, the lack of manpower and cold winters were further reasons for the rest of people to settle. Slowly, more families sold their animals and shifted from Kharnak to Kharnakling. Between 1991 and 2009, the population of Kharnak has decreased by 80%. (Dollfus, 2013). As building land was available to every family at a relatively low price and other community members had already settled in Kharnakling, many built their houses in this era.

As in 1991, the Manali-Leh highway was also opened for civilian travel, Kharnak all of a sudden has found not be far off anymore, with more tourists making their way to discover the nomadic life, going on treks in the region and also leaving their traces and rubbish.

From polyandry, which was once widely practiced, the model shifted towards nuclear family. This created an overload of work to be carried out by only two adults. Usually, there was at least one family member working as a shepherd, there was the family head taking care of administrative matters and trade journeys and then the wife taking care of the household, children and weaving textiles. In a nuclear family structure, two people have to share all of this work of at least three people.

Meanwhile, in Kharnakling, euphoria was great as the settlers temporarily enjoyed things they never had before. The winter was less cold than in Kharnak and this made daily life much easier. The workload decreased as there were no more animals. However, they soon realised that urban life requires for a lot of cash which the settlers could only earn by daily unskilled labour. For most of the families, especially the elders, the adaptation has been a difficult process and lasts until today. The sense of territorial identity connects them with Kharnak, yet there was no way to go back as all the animals of the families were sold and often, the young and agile family members did not want to return to pastoral life. As they now live in a cash-economy, their outlook on the material way of life has also changed and with some, given rise to greed. In a materialistic, anonymous environment many people need to show their status by the things they own. Kharnakling gave the nomadic people from Kharnak a fresh opportunity of gaining their living. Those who have become rich show off their wealth and consider themselves part of the middle class, rather than their status of Scheduled Tribe.

At the same time, this meant that many animals were sold to the Kharnakpa who stayed in the original place which increased the average size of their flocks. This has led to an increased workload for the Kharnak families, who had mostly 200 to 300 animals before. It provides the families a steady income but at the same time leads to the abandonment of traditional, time-consuming practices such as weaving their tents from yak hair, making yak leather boots and other local artifacts.

Many women in their early 30s, whose families had settled after their schooling, have still learnt weaving in their youth and are therefore they are able to pass on their skills. Also, they are keen to try a new approach on weaving, designs and techniques. These talents and open-mindedness are essential for any forward movement when working on ancient craft techniques.

Latest Observations – the 2010s

There is the first generation born in Kharnakling who only know Kharnak from stories told by adults. Inevitably, ties with their native land have loosened. These young individuals identify themselves as town children, living a life distant from their parents. The children have grown up with TV and mobile phones. Most of them own smartphones in their teenage years. As a consequence, they are informed of what is going on in the world, strongly connected on social media to both their friends from Changthang and following world football stars.

The community in Kharnak becomes even smaller in winter. Many women spend the winter months of January and February in Kharnakling. There they stay with their children who are on winter holidays and during the rest of the year live in a hostel at school.

However, the life in Kharnak doesn’t stop and in many families the flock of goats has increased in size. This is due to the high demand for pashmina, the fine down of the Changthang goat. This has created a stable income for the Kharnakpas.

It becomes clear that it is not too late to work with and encourage people to continue their traditional crafts. I see it as a time of great opportunity because there is a large group of “teachers”—the elders who can pass on traditional skills and knowledge, such as spinning and weaving various artifacts. At the same time, there is a large group of “students” who have a chance to learn something new.

Of course, it is a serious challenge to motivate young people to learn skills which they consider to be out of time but I see it as the only way to lay a foundation for carrying on their weaving tradition. Through our and their connection through social media, it can be a motivation for them to learn the skills. Seeing that people all over the world express admiration for their mother’s and father’s art, and also purchase the traditionally made Kharnak textiles, can be an eye-opener to the significance of their ancestors’ artifacts.

The opportunity arises to connect two generations and their awareness of the common heritage.

The beginning of We are KAL

In 2014, I started a personal research that stemmed from my own curiosity on the subject of hand-made textiles. At this time, I had been working in the luxury industry in Delhi for several years. Being in this environment made me acknowledge actual luxury: a product which is made with attention, time and by hand. Consequently, I wanted to commit my time to this and took a break from my work in the conventional luxury sector. I had a key aim: to find natural fibres, handspun and hand-woven on traditional looms of the regions, dyed with plants and made in a local environment instead of a centre. After nine months of research, this project turned into a business called We Are KAL, based in Germany and India. Our focus is on the making of a textile from “source to stitch”. We are using the traditional techniques of the communities we work with and beyond making beautiful textiles, our aim is to encourage these practices among the younger generation.

Since September 2017 I am working at We Are KAL full-time, before this I still had a part-time job. The operational costs of the business are covered through orders and I receive a manageable, monthly income. As the sole proprietor, I carry all financial risks and costs. In return, I have 100% ownership and therefore, can decide how to use our revenue. Members of the team receive income through our ongoing production. With us, their salary is above the average salary for the weaving/spinning/dyeing as we want the practice of the craft to be a profession with an income one can live with and is secured.

When I first set off in February 2014, I discovered eri silk in Assam where I continue to work ever since. Eri silk is extraordinary as the silkworm is not killed during obtaining the silk. It is therefore also called peace silk or ahimsa (“non-violence” in Sanskrit) silk. It is woven on simple fly shuttle looms by women in their homes in a rural area close to the capital Guwahati. When required, it is possible to dye the yarn using local plants.

Being isolated in Leh in the late spring, I dedicated my time to research in the library. Here I found reports of the Sheep Husbandry Department, describing the wool production in Changthang as well as the important book Living Fabric by Monisha Ahmed on the Rupshu textiles. In this way, I found out about the migration of nomadic communities, caused by modernity in the city, yet the lack of basic facilities such as education, healthcare and technological advance in the Changthang Plateau. The case of the Kharnak people and the social change of urban migration this community has faced in the last decades caught my attention. As mentioned, a large part of the Kharnak community had already settled in Kharnakling.

The Kharnak community has been making textiles over centuries using the wool of their animals. The interesting thing about their products is how they are used in everyday life and the deep connection between the makers and the herds of their animals. Textiles such as saddlebags were used to transport their belongings, the big blanket “tsug dul” to warm the nomads in the cold nights and the straps of the yak wool and yak hair textile made to build their tent called “reibo”.

As the people of Kharnakling were close while I lived in Leh, I went there to meet them and talk about wool and weaving.

Craft as a means of communication

To reveal a textile, it is necessary to know its origins, its meaning and purpose. Combining authentic Kharnak wool with the region’s traditional skill of backstrap loom weaving in Kharnakling, a connection between two places is created. Sourcing the wool from Kharnak, from the people who still keep the animals and live the harsh life on the Changthang Plateau, set the foundation of the making of our textiles.

More precisely, I could make use of the abundance of wool from Kharnak, where families keep more animals than two decades ago (up to 600 animals per family). The people there are extremely occupied with the animals, more than ever before, with fewer people to help. Contrarily, in Kharnakling the lack of animals creates a void of occupation for the people. As already stated, people now do casual labour, which only demands physical fitness. Yet there are many individuals having the skill and potentially, also the time to make the traditional textiles.

Rising popularity of natural textiles with a story

The textile supply chain has become complex and the making of a garment is scattered all over the planet. As a result, society is now questioning how, where and by whom their clothes and also other textiles, are made. At the same time the popularity for sustainable, slow-made textiles and handcrafted items has increased and we can see a shift in people’s buying behaviour. Additionally, there is a growing tendency of purchasing a product with a story at a higher price, than a similar one without a story at a slightly lower price. This is still a niche sector and does not apply to the average consumer but it is increasing. It is a good time to introduce rare textiles such as those from Kharnak.

The more a natural fibre is made traditionally and by hand, the lower is its carbon footprint. In our production chain, the only machine-made task is the carding of the wool. Carding wool means combing the wool into finer fibre and removing the hair, making it ready for spinning. This is a task requiring less skill if done by hand and the result is a coarser yarn with a rough feeling. This is why we opted for machine treatment in this step. Nevertheless, hand-spinning and hand-weaving requires great skill and has its very own look. It shows the imperfection of yarn thickness or irregularities in the weaving which are all signs of craftsmanship and genuine hand-work. This is why these steps carry such importance in the making process.

Fusion of traditional and modern

During my work, I have come across incredible textiles, mostly seen in a very worn condition with a pale look of the dyes. These are antique pieces and have their own charm and can be interesting for textile connoisseurs.

However, when making contemporary products, it is important to keep in mind the preferences of the potential customer in today’s world. It is often not enough to simply continue the designs that have been there for decades and centuries. Also, the surrounding adds to the design of a textile, especially concerning size and thickness. Look at the example of the tsug den, the carpet to sit or sleep on, which traditionally only measures 175cm in length and 90cm in width. This size fits perfectly into the local tents and is long enough for the people to sleep on. However, this is not a very common carpet size used in Western households. Here it is essential to adapt, for example, increase the length and make the carpet into a runner, which fits well into common hallways. Also, the traditional blanket tsug dul will most likely not be used as a blanket in Western homes, because it is very heavy, around ten kilos for a size of 200cm x 210cm and might be itchy to some people. The weave is very loose, and the yarn can fall out if it is heavily used as a rug. Therefore, we have adapted the weave of the tsug dul so it has same solidness and serves more as a big rug.

Creating a high-quality product to us also means to exclusively use natural wool and when required, dye wool with colour obtained from local plants. We are only at the very beginning here but would like to show two examples of how we have advanced so far and what we have noticed.

Conclusion

Age-old traditions are disappearing worldwide, along with their textiles and sustainable practices. Many of us, feel a certain regret watching these valuable skills becoming lost. In our time, this is not surprising and a natural reaction to how complex our lives have become, abundant with products and a changed lifestyle. Usually, we do not sit by the loom before the winter comes to weave the fabric for a new coat. Most of us do not rear animals at all, therefore we do not spin our animal’s hair to make ropes. The most unfortunate part about it is that we do not even know how to do it anymore. However, there are still some people on this planet who have the knowledge and skills to create these meaningful and thoughtfully crafted items.

The lifestyle of the Kharnak people is an exceptional example of sustainability. The fibres of their animals are converted into different products, all covering the needs of daily life. The milk is processed into different dairy products, the meat is consumed and the leather used for soles and other useful products. Even the plastic of food packaging purchased from the city is well reused: maggi noodle bags become sugar bags for the shepherd’s daily tea in the mountains, condensed milk tins are made into spinning bowls. Documenting and sharing these skills will inspire many people and can also trigger a change in behaviour of people unfamiliar with this lifestyle.

The Kharnakpa’s lifestyle is still sustainable and mostly self-sufficient, but this is also changing. For example, instead of the intricately woven yak hair tents reibo, nowadays more and more white cotton tents can be seen in the settlements. These are given free of cost by the government but do not keep enough heat and are not waterproof. Also, instead of using only wool yarn for the traditional carpets, more and more acrylic yarn chemically dyed in bright colours often dominates a carpet. These are just small examples showing the disappearance of traditionally made textiles from daily life.

Bibliography

Books

Ahmed, Monisha (2002). Living Fabric: Weaving Among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya, Orchid Press, Bangkok.

Dollfus, Pascale (2012). Les Bergers du Fort Noir, Nanterre Société d’Ethnologie.

Singh, K.S. (1994), The Scheduled Tribes, Oxford University Press New Delhi.

Articles

Dollfus, Pascale (2013) “Transformation Processes In Nomadic Pastoralism In Ladakh,” Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 32: No. 1, Article 15.

Tsewang Namgail & Yash Veer Bhatnagar & Charudutt Mishra & Sumanta Bagchi (2007): Pastoral Nomads of the Indian Changthang: Production System, Landuse and Socioeconomic Changes, Springer Science and Business Media.

Ajit Chaudhuri, Change in Changthang: To Stay or to Leave? Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 35, No. 1/2 (Jan. 8-14, 2000), pp. 52-58.

Monisha Ahmed, The Politics of Pashmina: The Changpas of Eastern Ladakh in Nomadic Peoples, New Series, Vol. 8, No. 2, Special Issue: Whither South Asian Pastoralism (2004), pp. 89-106, White Horse Press

Sarah Goodall, Changpa Nomadic Pastoralists: Differing Responses to Change in Ladakh, North-West India, Nomadic Peoples, New Series, Vol. 8, No. 2, Special Issue: Whither South Asian Pastoralism (2004), pp. 191-199, White Horse Press

Reports

District Statistical Handbook 2015-16, District Leh, Ladakh, J&K, India

Interviews

Interview with Tsering Angtak, 13th July 2016 and 4th July 2018, village Kharnakling, Leh, Ladakh, India.

Interview with Tsering Angchok, 26th June 2014, Yakhang, Kharnak, Ladakh, India.

Interview with Karma Angmo, 1st July 2018, village Kharnakling, Leh, Ladakh, India.

Author

Catherine Allié is the founder of the textile company We are KAL. Besides creating a social impact, she also wants to bring about ecological and cultural change: income for lost craft abilities, resource-friendly textile production and the revelation of unique culture and lifestyle. She is based in Ladakh, Himalayan India where she works with nomads and settled nomads on their characteristic textile art.

Catherine Allié is the founder of the textile company We are KAL. Besides creating a social impact, she also wants to bring about ecological and cultural change: income for lost craft abilities, resource-friendly textile production and the revelation of unique culture and lifestyle. She is based in Ladakh, Himalayan India where she works with nomads and settled nomads on their characteristic textile art.