A creative trio revive the legend of Hong Kong’s mermaid as part of a cultural journey across the world.

(A message to the reader.)

Music by Senju Hitachi (SekikomiGohan), Ayami Charlie Oki-Siekierczak (JP)

The trio of artist Alysa Leung, scholar Dr. Evelyn Wan, and filmmaker Anson Sham engage in “ongoing oceanic research” that connects mythical sea beings, feminism and journeys of migration.

Beyond the Shore invoked the mermaid myth of Lo Ting and the pirate queen Zheng Yi-Sao. This was intertwined with the personal stories of the performers.

Hong Kong mermaid Lo Ting

Sculpture of Merman “Lo Ting” (by Jimmy Keung) in the exhibition Maritime Crossroads: Millennia of Global Trade in Hong Kong (帆檣匯港:世貿千年), organized by Hong Kong Maritime Museum

In the late Eastern Jin dynasty, a rebellion broke out in China against the government. This event is historically referred to as the “Sun En and Lo Chun Rebellion”. Sun En was Lo Chun’s brother-in-law. After the death of Sun En, Lo Chun was chosen as the main commander and took the lead in continuing the resistance. They fought for nine years, eventually ending up in Canton. Accepting defeat, Lo Chun and his men jumped into the ocean.

Legend has it that he and his men turned into half-human and half-fish hybrids, ended up on Hong Kong’s Lantau Island, and led quiet lives as fishermen. These early Hong Kong settlers were mermen and mermaids, male and female hybrids… They have fish heads and human bodies, with fair skin, yellow hair, and yellow eyes. They lack the ability to speak, but they can smile.

From this emerged the mythical mermaid Lo Ting, representative of the Tanka people, a nomadic minority who live on boats in southern Hong Kong, considered its first people. They are associated with the “pink dolphin”, which became the mascot of the island’s handover to China in 1997. Lo Ting has been the subject of erotic “saltwater girl” narratives featuring sex slaves and mistresses kept in fish ponds.

Lo Ting has become an allegory for a Hong Kong that has been oppressed, a weak feminised body that is tied up and exploited.

Alysa had relatives who were “water people”. She remembers how they were discriminated against at school. “The teachers would pick lice from their hair and call them dirty and uneducated people.”

A forgotten pirate queen, Cheng Yat Sou

During their research, Evelyn was struck by the repression of other mythical females of the sea.

“We went to the coastal defense museum as part of our research. There was a display saying that, across from the water, the temples were built by pirates who used to be very active around Hong Kong waters. And I looked at that and turned to Alysa, and I was like, hey, but do you know about the wife?”

Cheng Yat Sou was originally a Tanka prostitute. She was captured by the pirate leader Cheng Yat and became his wife. Together, they ruled over six fleets and led the biggest fleet, the “Red Flag Fleet”. After Cheng Yat’s death, she remarried their adoptive son, Cheung Po Tsai, and took control of the pirate federation. She established “laws” and a “passport” system to run her federation. At its peak, the confederation had over 2000 ships and 70,000 personnel.

The story of Cheng Yat Sou is a triumph of the Tanka people as represented by a female figure of the sea.

A personal diasporic story at sea

The performance combines Evelyn’s life story with the embodied actions of Alysa’s dance and Anson’s visual and sound design.

“My maternal grandparents had an arranged marriage in Indochina, French-controlled territories of Vietnam and Cambodia. My grandfather came from Saigon, and my grandmother left Phnom Penh with a maid in tow to marry him. My maternal family are Vietnamese and Cambodian Cantonese-speaking Chinese,

“Through my family’s diasporic heritage, I questioned what it means to be from Hong Kong, which has been a hub for the migratory movement of people throughout this region.”

Further to this, Evelyn is puzzled by a missing bloodline. “Growing up, people would tell me, ‘You don’t look fully Chinese, so what are you mixed with?’” She has since come to believe that she is part Parsi, of Persian heritage, though it remains unverified.

Dancing oceanic stories

Alysa’s story reflects the changes in Hong Kong with the handover to China.

“I was born in 1997, which was the year of Hong Kong’s return to China. I think many artists and people of my generation always question our roots and our identities because we are not colonial British nor simply Chinese, and we are always in between. If Hong Kong is a place, it’s not just a place, it’s also a peninsula, and a set of islands, so it’s a complex of waters and land, instead of just a land civilization.”

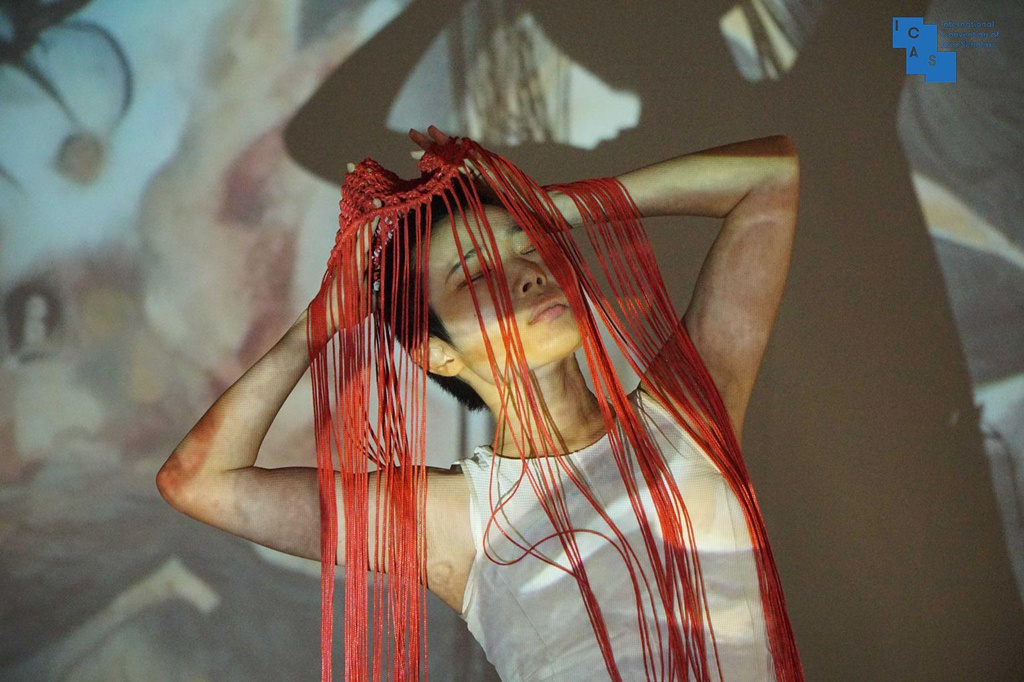

Alysa’s role as the performer was to embody the story.

“The question of embodiment for us is really important in terms of how we experience the stories. So much of that story is about the oppression of the body itself. So, we have to use the body as a medium to show the resistance of the flesh. We need to assert the presence of our physical bodies in space so that we can make that voice heard. Even if we don’t speak and we don’t use text, the body still holds that power of retelling the story and claiming a different narrative.”

Flowing through the feminine

For Alysa, what underlies their project is a quest to acknowledge the feminine as a fluid element.

“We want people to be more connected with nature and to go with the flow of the nature of one’s body, especially the female body. We always have our monthly period. It’s in our nature. So we want to connect feminine and natural power.”

They plan to continue this “artistic research” throughout East and Southeast Asia. Their next focus is South Korean female pearl divers, Haenyeo, of Jeju Island.

“Beyond the Shore” core team members at the post-show talk: Anson, Evelyn and Alysa (from left to right)

About Alysa Leung

I am an artist and dramaturg based in Hong Kong, working between Asia and Europe. I am interested in exploring the interconnections between body, site, and identity through embodiment. I believe theatre is an experiential space where alternative stories can be heard, conveying our worldviews through the waves of time. Visit www.alysaleungprojects.com.

I am an artist and dramaturg based in Hong Kong, working between Asia and Europe. I am interested in exploring the interconnections between body, site, and identity through embodiment. I believe theatre is an experiential space where alternative stories can be heard, conveying our worldviews through the waves of time. Visit www.alysaleungprojects.com.

About Evelyn Wan

I am an artist-scholar based between the Netherlands and Hong Kong. My research and performance practice intersects technology, colonial and inter-Asian ocean histories, mythology, and spirituality. Visit evelynwan.com.

I am an artist-scholar based between the Netherlands and Hong Kong. My research and performance practice intersects technology, colonial and inter-Asian ocean histories, mythology, and spirituality. Visit evelynwan.com.