Papercutting is one of China’s key cultural exports. The industry has developed without interruptions for over 1,500 years. It flourished during the Cultural Revolution as a mechanism for propagating Chinese Communist Party (CCP) values. During the mid-1980s, a government-endorsed folk art revival restored ethnographic diversity to the sector. Between 2006 and 2009, the distinct papercutting traditions of over 60 regions were inscribed into the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. However, within five years practitioners of these “ethnocentric” varieties of papercutting were calling for greater government protection against free market forces. This case study examines the effects of the introduction of CNC cutting into the Chinese papercutting industry.

What is papercutting and why is it Important?

Chinese papercutting (剪纸) involves creating a concatenation of perforations into thin fibre-based substrates to form an image. One of the earliest accounts of the practice in China dates back to the Western Han Dynasty (206BCE – 9CE). A shaman in the court of Emperor Wu Di summoned the presence of a deceased concubine using a papercut of her likeness and a lantern. The portrait was most likely cut from hemp. The invention of modern pulp strained paper occurred later in 105CE.

Offerings to the deceased were one of the earliest applications of papercutting. The practice of cutting paper effigies developed around the sixth century in response to theft from grave sites. Papercutting is also a manifestation of totemism, with particular reference to magico-religious practices. Pasting up a papercut of a rooster, for instance, was thought to protect a dwelling. Papercuts were, and remain, an integral part of the Spring Festival. The practice of decorating dwellings with papercuts for good luck and leaving them to the elements remained prevalent in villages of China up until the mid-2000s.

Most significantly, papercutting has been recognised as a form of ethnography since the late 1920s. Chinese papercutting is a repository for maternal traditions, from compositions that adorned the “wedding chamber” to hand-bound booklets about “…hunting for ginseng”.

Papercutting varies between regions in China in the equipment used, techniques employed and the subject matter depicted. In 2014, Yu-Chun Huang, from The University of Leeds identified 40 distinct Chinese papercutting styles in The Origin, Classification and Evolution of Chinese Paper Cutting.

A Timeline of Resistance

Zhou Shuying is a third generation papercutter from Yuxian. She is an advocate for the preservation of traditional Chinese papercutting techniques. In 2013, she stated in an article in the China Daily of the introduction of CNC cutting, “The impact is huge… many artists worrying about how to make a living faced with the technology trend.” She is also of a minority of traditionalists that believe papercutters should not use pencils to pre-draw their designs.

Before the post-digital era, defined by the ubiquitous integration of digital technology, competition for the traditionalists was catalysed by the availability of photocopiers. During the mid-2000s, it was commonplace for menial workers in Chinese villages to uptake the commercial production of papercuts to meet seasonal demand. For example in Feijiacun, a village then on the outskirts of Beijing, the TV repairman produced papercuts using photocopies and a box cutter.

The propriety of many papercutting techniques has been safeguarded by the family unit. However, the availability of photocopiers enabled democratic entry into this exclusive ‘guild’.

Within China, the transfer of papercutting skills was often intergenerational. The intervention of this analogue cum digital technology enabled democratic entry into an exclusive cohort. This sacrilege was compounded by an indiscriminate appropriation of the papercut designs. The papercuts became, at best difficult, to classify. Subsequently, as their origins became indeterminate the ethnographic value of the papercuts was compromised.

By the early 2010s, retailers in Chaoyang District in Beijing were favouring stickers featuring papercut designs printed onto clear film. Over the next five years, traditional motifs laser cut into a “paper” of felt-like consistency came to dominate the Chinese domestic market.

Unlike the rise of the cottage industry of unskilled papercutting driven by analogue technology, the digitally produced stickers and CNC papercuts uniformly referenced a style from Shaanxi Province.

The mass-produced papercuts in the post-digital era use an aesthetic that dates back to the 6th Century CE. However, unlike their organic counterparts, these synthetic felt-like cutouts do not erode when exposed to the elements.

Erasure and emergence

In October 2018, the building that housed the Foshan Papercutting Institute cum Folk Art Institute (FAI) had been demolished by developers. The practitioner in the nearby Ancestral Temple employed an indeterminate papercutting technique to approximate a Shaanxi style of papercuts. Emerging during the Song Dynasty (960 – 1127CE), Foshan papercutting has evolved over a 1000year period. Realism and elegant lines make this regional variation unique. These distinct qualities also reflect a British presence that began with the Treaty of Nanking at the end of the Opium War (1839-42). During the Qing Dynasty, papercutting from the region was the first to be internationally exported.

Image reproduced from Kong Ho, “Reverberating Chinese Traditional Folk Art in a Contemporary Context,” History Research 3, no. 1(2013): 34-43. This photograph documenting Foshan papercutting was taken at the FAI it 2011

This image was photographed in the Ancestral Temple in close proximity to the demolition site of the former FAI site in October 2018. The diversity in knives, which is characteristic of the Foshan papercutting technique, is absent. The imagery is also inconsistent with the style of papercutting that is endemic to the region

The father of the papercutter, Wen Sheng Yang, is a celebrated practitioner who trained at art school in Shaanxi Province. He said of Foshan papercutting, “When I am in Foshan, my papercuts are Foshan papercuts.”

Often referred to as “living fossils”, the Shaanxi style has become commonly recognised as “traditional” in the Chinese papercutting vernacular. It is indigenous to the agricultural region near the Yellow River, the birthplace of the medium between 206 – 23 BCE. It is characterised by a series of distinctive cut marks, such as the “saw tooth”, used to create a stereoscopic effect. The patterns are not unlike the system of lines employed by European metal engravers to create three-dimensional tone. Shaanxi papercutting has remained relatively unaltered, in both subject matter and aesthetic, since the sixth century CE.

Without government intervention, the diversity of Chinese papercutting may have been completely eradicated by the “universalism” imposed by corporations that control the “means of production” during the post-digital era.

Papercuts as art and propaganda

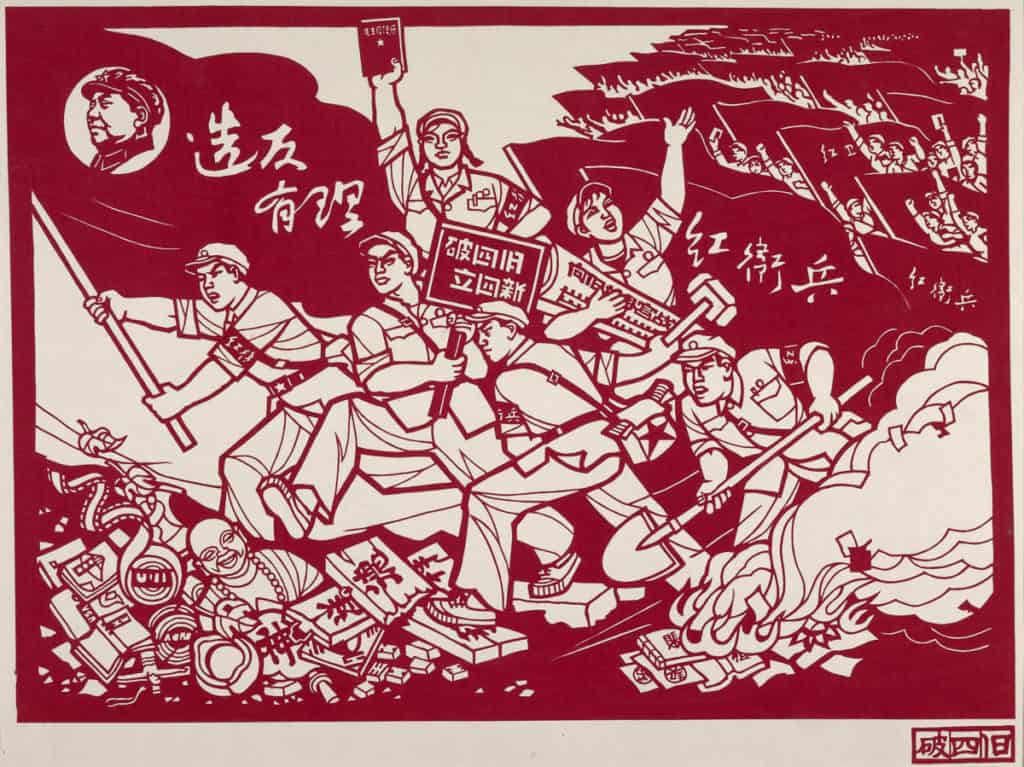

There is irony in the recent appeals from ethnographic practitioners, like Shuying, for government protection from free market forces. The papercut composition from circa 1970s, Eliminating the “Four Olds” illustrates a policy of the CCP that commenced in 1966. It involved the destruction of “old ideas, old culture, old customs and old habits”. The papercutting of propaganda employing a sanctified social-realist style from Russia flourished for a period of fifteen years. This was at the expensive of ethnographic diversity. Both the content of the compositions and their ritualised applications were regulated. However, the practitioners were able to maintain the regionally specific production techniques that made them distinct. This enabled the re-emergence of a plethora of papercutting traditions during the 1980s in what became known as the The Folk Art Revival (FAR).

Reproduced from Ann Arbour, “Rare Chinese Papercuts, Liberated from U-M Storage Room, Now on Display.” University of Michigan, accessed 22 May, 2017, http://ns.umich.edu/new/multimedia/videos/20031-rare-chinese-papercuts-liberated-from-u-m-storageroom-now-on-display.

Hou Youmei is a primary example of the CCP’s efforts to restore cultural diversity. She was discovered by the director of the “Arts Center of the Masses” of Tonghua City. She was, subsequently, educated at the Lu Xen Academy of Arts between 1985-7. Hou proliferates Manchurian folklore through her hand-bound books, papercuts and sculptures. Presently located in San Francisco, she has exhibited extensively throughout Europe and Asia.

Another papercutting exponent to emerge from the FAR, is New Wave visual artist Lu Shengzhong. Lu commenced his investigations into the folk art as a student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. He was heavily influenced by Western modernism. Lu examined aspects of papercutting using a structuralist framework, with a particular emphasis on the magico-religious aspects of the medium. This manifested in a series of large scale installations of papercut “moppets” designed to “call the spirits”. Lu has also exhibited extensively throughout Asia, Europe and North America.

In October 2018, amidst the decline in localised papercutting production, XC HuA presented a contemporary interpretation of the medium by Chinese Canadian artist Fred HC Liang. The professor at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design presented towering architectural forms. The sculptures were constructed by securing “scrolls” of papercuts to steel cable. The incised imagery is gestural, organic and abstract. The installations are referential of Chinese papercutting in technique, aesthetic and application. The artworks are allegories, with dialogues exploring the historical relationship between the Chinese and Europeans. The exhibition was acclaimed in both the Beijing Art Scene and the East Coast of the United States of America.

Chinese artists utilising the medium of handcut papercutting have been by and large unaffected by the integration of CNC technology into industry.

Upgrading Tradition

In 2012, the term “post-digital” was applied to the material of paper by Alessandro Ludovico in the seminal publication Post-digital Print: The Mutilation of Publishing Since 1894. In this same year, design company O3 Design Studios emerged. Founded by a couple of local designers, their papercut maps became a sensation in Beijing. The unlimited editioned multiples were juxtaposed with contemporary artworks in the city’s principal art precinct 798 Art District in Dashanzi. The designers are unapologetic technological determinists. In accordance, they exploit the accuracy of CNC technology to create products unachievable by hand.

Conclusion

CNC cutting is the most recent and potentially the most divisive of technologies to be introduced into the Chinese papercutting industry. This is primarily because ethnocentric papercutting practitioners, by and large, do not have the consummate skills required to control the “means of production”.

Prior to the commencement of post-digitalism, ethnocentric practitioners of papercutting were subjected to other market and political forces. The photocopier, for example, enabled unskilled workers to compete with the papercutting practitioners who utilised tacit knowledge passed down between generations of families. The CCP’s policy of sanctifying social realist art between 1966 and the mid-1980s also affected the ethnographic diversity within the sector.

Although the museum and gallery sector remains a bastion for handcut paper, it presently accommodates an elite echelon of the sector. Subsequently, many distinct variations of the medium are at risk as, presently, the corporations producing and distributing papercuts preference a single style. Shaanxi papercutting has consequently become synonymous with “traditional” in the Chinese papercutting vernacular.

Further reading

Ann Arbour, “Rare Chinese Papercuts, Liberated from U-M Storage Room, Now on Display.” University of Michigan, accessed 22 May, 2017,

Sun Bingshan, Chinese Paper-Cuts (Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, 2007).

Feng-Kao Chang, “The Art of Papercut,” China Reconstructs, no. December (1973).

Florian Cramer, “What Is ‘Post-Digital’,” APRJA, 23 January, 2014, accessed 1 February, 2019,

Tillman Durdin, “China Transformed by Elimination of ‘Four Olds’,” The New York Times, 19 May, 1971.

Mareile Flitsch, “Papercut Stories of the Manchu Woman Artist Hou Yumei,” [In English] Asian Folklore Studies 58 (2000): 353.

Chang Feng-Kao, “The Art of Papercut,” China Reconstructs, December (1973): 30-31; and, Eric A. Hyer, “Art & Politics in Mao’s China, ” Kennedy Center, accessed 21 November, 2018, .

John Caspar Lavater and Thomas Holcroft, Essays on Physiognomy, Also One Hundred Physiognomical Rules, and a Memoir of the Author (15th Ed.) (London, Great Britain: William Tegg and Co), doi:10.1037/12870-000.

Dale Hoyt Palfrey, “Mexico’s Traditional Papel Picado: Classic Art for a Mexican Fiesta,” Mexconnect, 1 January, http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/1567-mexico-s-traditional-papel-picado-classic-art-for-a-mexican-fiesta.

William Ivins, Prints and Visual Communication (London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1953).

Beck Ulrich, Natan Sznaider, and Rainer Winter. Global America? : The Cultural Consequences of Globalization. Studies in Social and Political Thought. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2003.

Yu-Chun Huang, “The Origin, Classification and Evolution of Chinese Paper Cutting” (PhD diss., University of Leeds, 2014).

Hang Jian, “The Chinese Art of Papercutting,” Youlin Magazine, 24 August, 2016, accessed 19 November, 2018.

David Revere McFadden, Holly Hotchner, and Museum of Arts and Design (New York N.Y.). Slash : Paper Under the Knife (New York: 5 Continents ; Harry N. Abrams distributor, 2009): 220. Exhibition catalogue.

Susanne Schläpfer-Geiser, Scherenschnitte: Designs and Techniques for the Traditional Craft of Papercutting (Lark Books, 1996).

Emma Rutherford, Silhouette (New York: Rizzoli, 2009).

Joseph Shadur and Yehudit Shadur, Traditional Jewish Papercuts : An Inner World of Art and Symbol (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2001).

John Tomlinson, Globalization and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

Beck Ulrich, Natan Sznaider, and Rainer Winter. Global America? : The Cultural Consequences of Globalization. Studies in Social and Political Thought (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2003).

Ross Woodrow, “Lavater and the Drawing Manual,” in Physiognomy in Profile : Lavater’s Impact on European Culture, ed Melissa Percival and Graeme Tytler (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2005).

Li Xianting, “Major Trends in the Development of Contemporary Chinese Art,” China’s New Art, Post 1989 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Arts Centre and Hong Kong Arts Festival Society, 1993), XIX.

Daoyi Zhang, The Art of Chinese Papercuts. Traditional Chinese Arts and Culture. 1st ed. (Beijing, China: Foreign Languages Press, 1989).

Zhang, The Art of Chinese Papercuts, 18-19; and, “Chinese Paper Cutting Art,” China Icons, 8 December, 2016, accessed 20 November, 2018.

Tang Zhe, “Paper-Cut Artists Strive to Rise above Technology,” China Daily, 7 August, 2013, accessed 20 November, 2018, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/art/2013-08/07/content_16876760_2.htm.

Sara Zielinski, “Interview with Fred Liang,” Huffington Post, 24 February, 2016, accessed 20 November, 2018.

“Episode 1” in Explore the Silk Road: The Birthplace of our Modern World.

“Hou Yumei’s Page,” Chinese Cultural Foundation of San Francisco, 20 November, 2018.

“Installation of Fred Liang’s “Morning Song,” Milwaukee Art Museum, 2016, accessed 25 November, 2018.

Author

Pamela See (Xue Mei-Ling) is presently undertaking a Doctor of Philosophy at Griffith University in Queensland. Her research focuses on contemporary applications for papercutting. She has studied the technique in a number of provinces. Her artwork features in several institutional and corporate collections including The National Gallery of Australia, The Australian War Memorial and the Art Gallery of South Australia. During June and July, her artwork will be exhibited in Ephemeral Landscapes at the Museo Gustavo de Maeztu in Spain, My Optic at Arteriet in Norway and Crossing Boundaries at Art Atrium in Sydney.

Pamela See (Xue Mei-Ling) is presently undertaking a Doctor of Philosophy at Griffith University in Queensland. Her research focuses on contemporary applications for papercutting. She has studied the technique in a number of provinces. Her artwork features in several institutional and corporate collections including The National Gallery of Australia, The Australian War Memorial and the Art Gallery of South Australia. During June and July, her artwork will be exhibited in Ephemeral Landscapes at the Museo Gustavo de Maeztu in Spain, My Optic at Arteriet in Norway and Crossing Boundaries at Art Atrium in Sydney.