An iPhone memory prompts a conversation between Rajni Yadav and Kriti Sharma about the rich diversity of water spirits in Indian culture.

Kriti and I were discussing student work in my cabin at the college when, unexpectedly, a memory popped up on my iPhone—a photo memory album from last year, capturing the breathtaking beauty of Sonmarg, Jammu and Kashmir. I tapped play, and the video began, blending seamlessly with the serene sounds of the morning.

The clip revealed the Sindh River in Sonmarg, its crystal-clear waters revealing a vivid tapestry of algae gently swaying over smooth, time-worn stones. It was a mesmerizing sight, a testament to nature’s exquisite artistry. The river’s soothing rhythm filled the room, a melody of life and perpetual movement.

“The beauty of the Sindh River at Sonmarg,” I murmured, captivated, as we watched the pristine blue waters flow gracefully through verdant meadows, carving a path past a grand alpine hill. It was a vision of tranquillity—a vivid reminder of nature’s power and serenity in perfect balance.

I turned to Kriti and asked, “Do you know where the Sindh River comes from?”

She thought for a moment before replying, “From the melting snow, right?”

“Exactly,” I said. “The snow from the Himalayan peaks feeds the river. When snowfall is scarce, the water supply reduces significantly, impacting not just the river but entire communities.”

“We humans, animals, and all living things depend on water,” I continued, my gaze fixed on the serene video of the Sindh River. “Aquatic life also plays a vital role as the true guardians of waterways. They maintain balance, filtering pollutants, sustaining ecosystems, and ensuring the health of rivers, lakes, and oceans.”

Kriti nodded thoughtfully. “It’s incredible how interconnected everything is. Without aquatic life—like fish that maintain food chains, algae that produce oxygen, and turtles that balance ecosystems—rivers would lose their vitality. They’re the silent guardians of water’s purity and balance.”

Kriti smiled thoughtfully as she continued, “It’s fascinating how aquatic life and water spirits are woven into every aspect of our culture. In Indian mythology, Lord Vishnu, reclining on the serpent Shesha in the cosmic ocean, embodies the protective and life-sustaining essence of water. Lord Shiva, with the Ganges flowing from his locks, represents water’s ability to purify and transform. Similarly, Lord Brahma, seated on a lotus, symbolizes creation and spiritual purity.”

She paused and added, “Goddess Lakshmi, emerging from the ocean during the Samudra Manthan, links water to abundance and fertility. Her lotus seat symbolizes beauty and divine connection, rising unblemished from the water’s depths. And Goddess Ganga, personified as the river, often rides her vahana, the makara, a mythical creature with attributes of both a crocodile and a fish, emphasizing the life-giving role of rivers.”

“I remember! Anjali ma’am has those Kalighat paintings with Lakshmi seated on a lotus. And Vandana ma’am also has beautiful fish paintings from traditional Indian art styles.”

Similarly, in Gujarat, the vahana of Khodiyal Mata is a crocodile, symbolizing strength and adaptability in aquatic environments. These depictions emphasize the reverence for rivers and their life-sustaining qualities.

The Samudra Manthan also saw the tortoise, Vishnu’s second avatar, Kurma, supporting Mount Mandara during the churning of the ocean. This act reflects the vital role of aquatic creatures in maintaining balance. Myths often speak of fish, turtles, and other aquatic beings as protectors, guiding gods or humans in times of need.

These stories remind us of water’s sacredness and its integral role in sustaining life, inspiring a sense of respect and responsibility toward protecting aquatic ecosystems.

Kriti smiled thoughtfully as she continued, “Water isn’t just a resource; it’s revered as a life-giver. The Samudra Manthan also saw Kurma supporting Mount Mandara, highlighting the vital role of aquatic creatures. It’s a beautiful reminder of water’s sacredness, don’t you think?”

I nodded, smiling, “Absolutely! Water’s role stretches into astrology too. The zodiac signs Cancer and Pisces are both water signs—Cancer represents protection and adaptability, while Pisces reflects intuition, imagination, and a deep spiritual connection to the world. It’s a cosmic acknowledgment of water’s nurturing nature.”

Kriti’s eyes sparkled with excitement as she added, “It’s so true! These symbols are not just art—they’re deeply rooted in Indian culture and textiles. Take Madhubani art, for example, where fish motifs often symbolize prosperity. Similarly, in Gond painting, fish designs also hold significance. In West Bengal, fish motifs symbolise the region’s deep connection to rivers and the sea. Traditional art forms such as Kantha embroidery, Patua and Santhal mural paintings, and glazed terracotta feature fish designs, believed to bring good fortune. Similarly, in Odisha, fish and duck motifs are intricately woven into sarees like Sambalpuri, Viman, and Vichitrapuri. In Chhattisgarh, Dhokra metal figurines often incorporate fish motifs, reflecting cultural symbolism. Maharashtra’s Warli art depicts fish in a simplistic yet meaningful style, representing water bodies and sustenance. Meanwhile, in Chikankari embroidery, lotus motifs add a divine essence, symbolizing blessings and purity.

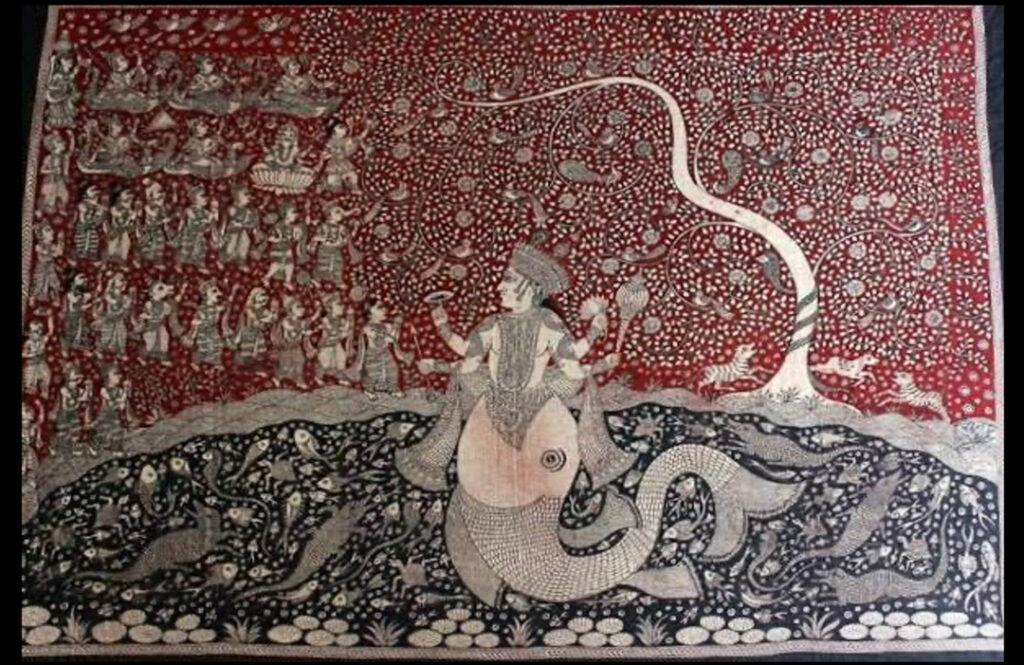

- Half-fish and half-goddess deities motif in Mata Ni Pachedi of Gujarat

- Matsaya avatar of Lord Vishnu in Madhubani painting

I leaned in, excited to share more. “Exactly! Maharashtra’s Paithani sarees reflect the sacred bond between water and life with lotus and swan motifs. Mata-ni-Pachedi, Gujarat’s sacred textile painting. is a remarkable blend of devotion, artistry and nature. This intricate folk art vividly portrays Mata in various divine manifestations, including Matsya Avatar, where she is portrayed as half-fish and half-goddess. The artwork also incorporates motifs of fish, tortoises, and lotus flowers, symbolizing strength, protection, and the cycle of life. Each element in Mata ni Pachedi reflects a deep spiritual connection with nature, making it a unique artistic and cultural heritage of Gujarat.

Kriti nodded eagerly, “I see what you mean! And what about Kalamkari art from Andhra Pradesh? The intricate depictions of Vishnu’s Matsya Avatar with fish motifs and waves are breathtaking.”

I smiled, “Yes, and it doesn’t stop with textiles. In Tamil Nadu and Kerala, marine life appears in jewellery and sculptures, with intricate carvings of Matsya and the use of pearls and shells reflecting the deep connection to the sea.”

Kriti looked intrigued. “So, water and its symbolism are everywhere, even in festivals, right?”

“Exactly!” I said, tapping the screen to replay the calming river video. “In places like Odisha, during Kartika Purnima, people honour water as a sacred element. These festivals and arts reflect how water is not just a resource but a living, breathing presence that nourishes and protects.”

Kriti’s smile widened as she reflected on our conversation. “It’s amazing how everything ties together—the water, the fish, the crafts, and even mythology. It’s like a complete circle of life and creativity.”

I nodded, “Exactly. Nature, mythology, and art—they’re all interconnected, just like the flow of this river. Water binds them all, shaping culture, tradition, and life itself.”

Through vibrant artworks and traditional crafts, our ancestors’ wisdom in understanding the sacred relationship with nature is passed down through generations. This legacy not only honours the guardianship of water and life but also inspires us to sustain these connections in our modern world.

In Delhi, the heart of India, the Hauz Khas Metro Station beautifully showcases this cultural heritage. The mesmerizing display of paintings, embroideries, and woven fabrics presents a rich collection depicting aquatic life across diverse cultural traditions. If you ever plan a visit, don’t miss this artistic celebration of nature’s beauty, balance and rich Indian culture.

So When are you planning your trip?

About Rajni Yadav

Rajni Yadav (PhD.) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Clothing and Textiles, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, with 15 years of academic and research experience. She expertise in natural dyeing, textile testing, value addition, documentation, and weaving techniques.A dedicated scholar and has authored two books— First on textile testing and Second on natural dyeing—and has over 25 research publications to her credit. Passionate about experiential learning, she has convened numerous workshops.

Rajni Yadav (PhD.) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Clothing and Textiles, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, with 15 years of academic and research experience. She expertise in natural dyeing, textile testing, value addition, documentation, and weaving techniques.A dedicated scholar and has authored two books— First on textile testing and Second on natural dyeing—and has over 25 research publications to her credit. Passionate about experiential learning, she has convened numerous workshops.

About Kriti Sharma

Kriti Sharma is an Assistant Professor at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in Vadodara, Gujarat, India. Passionate about preserving India’s traditional crafts, she has worked extensively on Salawas durries, Bagru prints, and Rajasthan’s rich embroidery traditions. Her past research includes exploring natural dyes from agro-waste, and she is currently focusing on Bishnoi embroidery of Rajasthan for her doctoral research.

Kriti Sharma is an Assistant Professor at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in Vadodara, Gujarat, India. Passionate about preserving India’s traditional crafts, she has worked extensively on Salawas durries, Bagru prints, and Rajasthan’s rich embroidery traditions. Her past research includes exploring natural dyes from agro-waste, and she is currently focusing on Bishnoi embroidery of Rajasthan for her doctoral research.