Kshitija Mruthyunjaya writes about a nine-day festival, during which Indians express their gratitude to everyday tools.

In our daily lives, we rarely think or pay attention to the instruments or tools that help us conduct our everyday activities with ease. From small items like a needle, keys, plough, butter churner, rolling pin to large ones that are deemed superior in terms of cost, size, power, speed etc like vehicles and other machines all aid us in one way or another. While the former hand-driven instruments are often associated with belongingness and fulfilling a human need for connectedness, the latter is usually associated with novelty and newness based on the human desire for invention and progress. In an era where new tools keep appearing and in most cases replacing the old and sometimes causing it to disappear, how does the practice of Ayudha Puja in India give value to the daily implements and help in aligning the two facets of existentiality—belongingness and novelty?

Ayudha Puja is celebrated on the eighth day of Navaratri, a nine-day festival where nine forms or avatars of Goddess Parvati are worshipped owing to different aspects of her strength, power and personality. Historically the eighth day was dedicated to worshipping weapons such as bows, arrows and swords as they were means of defeating enemies. In the state of Karnataka, where I come from, it is primarily celebrated to commemorate the slaying of the demon king Mahishasura by Goddess Chamundeshwari, an incarnation of Goddess Parvati. It is one of the most significant festivals in India to pay reverence to the tools that aid us and reminds us of the extraordinariness of our everyday implements. The Puja is considered a meaningful custom as it connotes that a divine force is working behind our everyday tools, allowing them to perform well and reminds us to give thanks to daily instruments. On the day of the festival all of the tools are cleaned (and painted if required), smeared with sandalwood, turmeric, vermilion and grandly decorated with flowers, sometimes plantain leaves and sugarcane.

Since the twentieth century, India, neither wholly new nor entirely old, has been a land of technological duality. It is both the “India of Oxcart and the India of automobiles.” Since the colonial times, indigeneity has not always been a virtue and at times, it connoted second-best. This made the foreignness of an electronic instrument or an automobile sometimes synonymous with prestige, social glory and cosmopolitan sheen of its owner. This mentality is challenged with festivals like Ayudha Puja that give us an opportunity to become aware and pay reverence to our traditional tools which have slowly been replaced with the new.

This day is a reminder that everyday tools and instruments whether old or new hold a highly functional/use-value and thus be given a commemorative value. In some cases, this commemorative value is heightened due to memory attached to the tool. For instance, my mother is closely attached to some of the objects passed on to her by her mother and grandmother, such as a tool used to churn buttermilk, a popular south Indian welcome drink. Other kitchen tools include a stone mortar and pestle, wooden rolling pin and board. Although these are replaced by the modern-day electric grinder and stainless steel chapati presser to cater to busy modern-day schedules, she still uses the traditional tools when time permits and handles them with great respect owing to its memorial value.

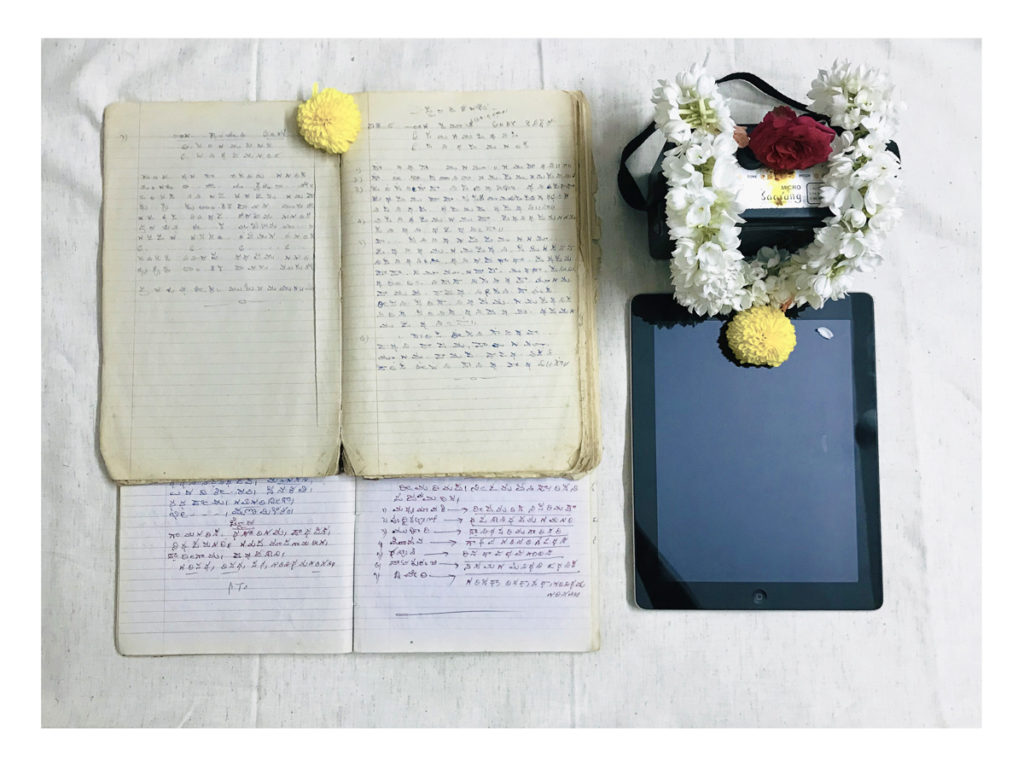

And when it comes to recreational tools, despite some of them losing their functional value with time, the radio/transistor, Tamboori (a musical instrument), worn handwritten musical lyrics, frayed printed books, landline phones are still considered significant in my family due to the memorial value they hold. They are commemorated during Ayudha Puja, which reminds us of the use-value they once held and the memorial value they hold now. They are worshipped alongside their modern replacements like mobile phone, Ipad or kindle and laptop that now stores music, lyrics, news, e/audio-books respectively.

On one hand, the co-existence of old and new sometimes creates clashes dismissing the new on the grounds that “in the land of ox-cart one must not expect the pace of a motor car.” Some criticise the introduction of the new or replacement of old: technological transfer from west to east takes away from the connectedness of a tool to its local needs and thus ignores the sense of belonging. On the other hand, modern tools and technology that has influenced India a great deal in the recent times to keep up with new age are seen as progress based on human interest in exploration, invention, and desire for new experiences. Whether this progress is culturally appropriated when it is initially introduced is still questionable in some modern-day implements. But over time we adapt to those implements and they adapt to us, giving it a local meaning. And this change irrespective of its scale, whether it is in the introduction of automobile or sewing machine, has become equally a part of every day with its indigenous counterpart in our households or social sector.

Kshitija Mruthyunjaya,Hand written music book, tamboori (music instrument) and IPad worshipped on Ayudha Puja,2019

Ayudha Puja thus helps us give value to our implements beyond the technological divide and helps us see them as a whole. The practise of worshipping the old and the new side by side during Ayudha Puja helps somehow neutralize the duality and helps them to become complementary to one another. It encourages acceptance and attributes the presence of ploughs, hammers, chisels, ox-carts and modern tools like automobiles, electric tools to local needs, personal taste and circumstances. It provides a platform for the alignment of the two existential sides of objecthood – belongingness and novelty.

Author

Kshitija Mruthyunjaya is an architect, designer and artist. After completing her bachelor degree in Architecture in Bangalore, India she moved to the UK where she pursued MA in Regeneration and Development and M.Arch (RIBA Part 2). She worked for a leading firm in the Bath, UK for several years before moving to Milan where she currently resides. Apart from architecture and design her passion also lies in textiles and writing. She collaborates with not for profit organisations and local artisans in India to keep traditional crafts alive and support economically challenged communities. Her main goal is to use her skills and knowledge in design as a regenerative action to create conscious and inclusive communities.

Kshitija Mruthyunjaya is an architect, designer and artist. After completing her bachelor degree in Architecture in Bangalore, India she moved to the UK where she pursued MA in Regeneration and Development and M.Arch (RIBA Part 2). She worked for a leading firm in the Bath, UK for several years before moving to Milan where she currently resides. Apart from architecture and design her passion also lies in textiles and writing. She collaborates with not for profit organisations and local artisans in India to keep traditional crafts alive and support economically challenged communities. Her main goal is to use her skills and knowledge in design as a regenerative action to create conscious and inclusive communities.