Utility store

On a humid Sunday, Jo McCallum begins a journey to understand the particular mystery that is bamboo in Japan.

(A message to the reader.)

It was a wet Sunday in late October 2016, warm and humid; a lazy day. I was staying in a hostel in Beppu (別府市), Ōita Prefecture (大分県) on Japan’s Kyūshū Island (九州). The city is famous for its onsen (温泉): steaming hot springs that whisper through the town’s drains like smoking serpents. It’s a highly active geothermal site, resting between the mountains and the sea. There’s an anxious energy about the place. It’s also the heart of the Japanese bamboo weaving community.

In August, I had arrived at Nichibunken (International Research Center for Japanese Studies), Kyoto, Japan to take up an AHRC International Placement Scheme (IPS) Fellowship. I’d come to study with the bamboo weavers, to explore their techniques and traditions. I was hoping to inform my practice research PhD, a project focused on crafting a pattern formation for material computation.

Chikuden House

Material computation is a form of expanded practice that operates as both a methodology and as a technical framework. It is used to model and fabricate material organisations that correspond to changing functional constraints. This approach is bio-inspired and therefore prioritises material distribution over traditional assembly methods (Oxman, 2012).

In researching the bamboo weavers, I was looking to identify meaning in the creation of form: to query whether the act of weaving structures provides a critical insight into the way we, as human beings, organise our existence (Heslop, 2011), and to understand bamboo, as both a sustainable resource and as a sacred material.

On that rain-soaked day, I was slowly beginning to understand that the bamboo weavers observe a very personal form of animism. They revere bamboo, simply, with focus, precision and grace, nothing more, nothing less. I say slowly because at that time I was still holding onto my theoretical agenda—the one I’d brought with me to Japan. That was, specifically, the need to identify and document Shinto-Buddhist traditions at the heart of this unique craft. Many Western art catalogues proposed such a link, I followed it, I wanted to find it. What I found were skilled practitioners, operating outside the norms of their culture, living and breathing bamboo. I found a community exploring the process of growth and engaged in the interplay of forces and materials (Ingold, 2012).

In my first week in Beppu, I met Mr Shimizu. SHIMIZU Takayuki (b. 1979) is a young maker, as bamboo weavers go. He’s an elegant, androgynous person, with an excellent grasp of English and generous spirit. He was Shimizu-san trained under the shy and talented master, MORIGAMI Jin (b. 1955). During our time together, he introduced me all over town, taking me to dinner and encouraging me to drink large glasses of Japanese whisky. He was my person on the ground in Beppu, although I was told by another that Shimizu-san had little idea what my work entailed.

And so, to Taketa, two and a half hours away from Beppu by train. The woman who’d told me of Shimizu-san’s secret also told me to go. She said “there are bamboo weavers there”, then handed me a year-old event catalogue, written in Japanese, but with pictures. My Japanese language skills were rudimentary. I knew take (竹) meant bamboo: I was drawn to the pictures. There was an image of a maker in his studio, a repurposed school, light and bright. I thought it was worth a shot.

It was something to do, rather than being stuck in the hostel, or heading to the bars as the other travellers planned to do. The train was old and quaint, with a smartly dressed conductor. We rode by the river, chugging our way through an array of seasonal beauty. I arrived in Taketa just as the rain died down. From the platform, I could see a tall, thin waterfall cascading down a rock face behind the station. The sound drew me in. I left and walked towards a bridge, where rain dripped from the nose of a bronze statue. I could see the old town on the other side, not new Taketa, but an old town, resting at the base of a mountain, atop which stands the ruins of Oka Castle (岡城).

I walked along the river. Again, I was drawn to the sound of the waterfall. I turned, and that’s when I saw it, the bamboo, waving at me. A huge weeping clump, on the far bank, swaying in the breeze, gesturing just to me. I’d heard about this phenomenon before, this kind of connection with the bamboo. It felt real. Like an affirmation, it whispered in my ear: “You’re on the right path, keep going”. And so, I spent that day walking, through a town at rest, closed, quiet. I took photos, I made a friend, a kind, mature, toothless woman, clearly pleased to see a stranger wandering the streets of her town.

Former craft centre

As I made my way up the hill I came upon a traditional Japanese house. It seemed deserted, so I peeked through the gate, only to find a man inside a tiny ticket booth. I paid the 350 Yen fee, then proceeded to the entrance and removed my shoes. The air inside the house was cool and fresh, akin to the wet grass outside. I was alone, free to wander from room to room. I sat upstairs and took in the view. I sketched the interior.

I was reminded of my undergraduate degree when I studied architecture, in Queensland, Australia. At one time I’d been obsessed with the ken (間), a traditional Japanese unit of length based on the size of the tatami (畳) mat. Once, I’d laboured late into the night, bent over the drawing board, trying to achieve a harmonious plan. Here I was amidst harmony. As the sun began to shine over the landscape below, I heard voices downstairs of other tourists, in my town, in my spot. I found out later the house was the home of an artist, TANOMURA Chikuden (田能村竹田) (1777 – 1835), formerly known by the surname Kōken (孝憲). He was a painter in the Edo period, renowned for his depictions of nature. I had wondered if it was an artist’s home.

Statue on bridge

The rest of my afternoon was spent walking and taking photos. I travelled past samurai houses and saw a group of Western classical musicians departing from one, filing into a row of black town cars. I was starving. The only place I’d seen open was Osteria e Bar RecaD (オステリア エ バール リカド), a small Italian bar and restaurant. I burst through the door with my Western bravado – a failing that masks my own anxiety. It was empty but for two people sitting at a table, working on laptops. A woman and a man. She leapt to her feet and told me they were not open, but with kindness. She said it was his place, and again, that it wasn’t open.

Apologising, I turned to leave, then she asked me what I was doing there, so I told her about Beppu and the bamboo weavers and finding Taketa. All the time she was translating for him. He reached for a flyer and gave it to me. On the front was an image of pieces of bamboo, illuminated by an unseen candle. It was advertising a festival of light and bamboo, running from the 18-20 November. In my head I thought, I can’t, I’d have to change my field trip plan, I’d have to go to Tokyo and then come back down again in a day. I thanked them and headed home on the train, past the volcanic mountain ranges, by the river, through Oita, back to Beppu and chicken katsu (鶏カツ).

In the coming months Taketa kept calling to me, in dreams, in little moments, bound by smell, and light, and sound. I had to go back; I couldn’t resist it. On 19 November, I arrived with a friend, the bamboo weaver YONIZAWA Jiro (b. 1956), a renowned maker. After that first visit, I had changed all my plans and used the last two days of my Japan Rail Pass. It worked, in fact. In accepting change I’d opened doors and created new opportunities all over Japan, but that’s another story. I spent my day in Taketa visiting basketmakers and imbibing bamboo. Heavy intermittent rain affirmed my sense of belonging, validating my decision to return.

Hajimi

I met the man in the first photo I’d seen, in that out-of-date guide. His name is NAKATOMI Hajime (b. 1974). Originally, he completed a degree in Business at Waseda University (早稲田大学). Waseda is amongst the best universities in the world. I’ve heard it described as the Harvard of Japan. But this path was not for Hajimi, he is a maker, with an infinity for systems logic and organic form.

In his studio, a former science classroom in that abandoned school, Hajimi showed me his work in progress and his methods. He explained that he was working on a commission for a hotel in Miazaki (宮崎市) on the southern end of the Island. I shared my plans to weave in steam-bent timber. His eyes lit up and he told me the hotel already has works like this. A quick Google search revealed that these had been created by a friend in Cumbria, Charlie Whinney, a graduate of Falmouth University: the man who taught me how to steam bend. There was an instant affinity between Hajimi and me, borne of shared practice, shared connections, and the unspoken understanding that we are both a bit different from the norm. As we talked, Jiro worked effortlessly to point out details in each piece of work, to explain the tools and techniques involved.

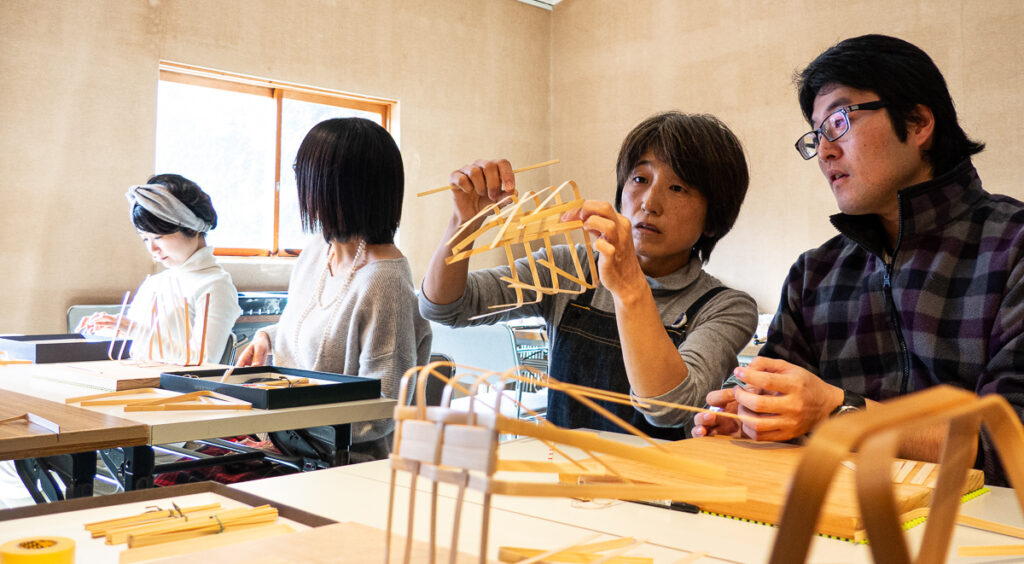

Box making workshop

From there, we took a short car journey back to town, where we fell upon a bamboo box making workshop. The technique reminded me of steam bending, as well as post and beam construction. We then went onto the Osteria e Bar RecaD (オステリア エ バール リカド). Jiro explained that it is a creative hub in the town, a place where artists, architects, and makers meet to discuss rural regeneration and regional identity. We stayed for a coffee and found ourselves amongst such a gathering: a talk on the establishment of the Art Hotel, a parallel cultural programme, a plan to bring people to this special place. I sat and listened, only able to understand snippets, but well aware that the conversation unfolding in front of me was one I’d heard before, in Penryn, Cornwall, on the forgotten South East coast of the UK. So many regional towns, passionate to encourage growth, to share their creative spirit, to retain their young. Jiro explained that he had to return home to Saiki (佐伯市) before dark. It was a long drive, through winding mountain roads. He encouraged me to stay and enjoy the bamboo festival that was about to unfold in the night.

- Before the light

- Illuminated path

The Taketa Chikuraku (たけた竹楽), the illumination event, is a festival of bamboo and light, established in 2000. Inspired by this, once a year Brisbane, Qld, hosts a sister festival, albeit smaller – a homage to this little town in the heart of Kyushu. Another serendipitous connection revealed. As dusk fell, I walked the streets as the locals began to light the town. They gestured to me, gave me a flame, and asked me to join them in lighting the town. Children approached me and ran away screaming with laughter; I was the only Westerner around. The pathways became more crowded, the darkness revealed the beauty of 20,000 bamboo lanterns, and I wandered as I had on that first day: up to Chikuden’s house, into the garden from which those musicians had emerged, where now an opera singer, dressed in red, filled the air with song.

I ran into Hajimi and his young family. I waved to strangers who excitedly waved at me. I stopped and looked at the details of large bamboo sculptures placed around town. Late that evening, I boarded the train back to Beppu and took one last glimpse at the little town that had changed my academic view in so many ways. Glistening in the night, it bid me farewell. One last gesture of repose.

For many, Taketa won’t stand out amongst the endless wonders of Japan, but for me, it will always be the site of my awakening. It is the place in which I stopped thinking with my head and instead followed my instincts. These were instincts that served me well throughout my international placement, which taught me to relinquish control, listen to the materials, and make from the heart. This was not a new message, but one I’d forgotten over time.

Now, in 2020, looking back, I wonder when I’ll visit Taketa again if I’ll see Mr Shimizu, Jin, Jiro, and Hajimi again. We had plans to make together, to return to Taketa, with architecture and basketry students, and a vision to work with bamboo, timber, and digital tools. Since I visited, KUMA Kengo (隈 研吾) has discovered the town and bamboo weaving. He’s even collaborated with Asics on a pair of bamboo-inspired trainers\I can see Hajimi’s influence in the work. In some ways, this ignites my fear of missing out, in others, I am bound to this place, and so I must keep working, here, in Queensland, in relative isolation, until we can all meet again.

References

Heslop, s 2011, “Basketry: Making Human Nature”, in Basketry: Making Human Nature, Heslop, S (ed), East Publishing, Norwich, UK, pp. 14-23.

Ingold, T 2013, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, Routledge, London: New York.

Oxman, N 2012, ‘Material Computation’, in Manufacturing the Bespoke: Making and Prototyping Architecture, Sheil, B (ed), John Wiley & Sons, London, pp.256-265.

Author

Jo McCallum is the Founder, The Fabricated Frame – Crafting Futures, a transdisciplinary studio exploring innovation through craft. She is a Digital Craft PhD Candidate, School of Architecture, University of Queensland (formerly AHRC 3D3 Studentship in Digital Craft, based at FoAM Kernow & the University of the Arts London). Maker, Academic, and Transdisciplinary Researcher, Jo McCallum is passionate about crafting futures. Her work is focused on elevating the perception of traditional craft via making, biotech, digital fabrication, and policy development. Jo is a STEAM Ambassador and an advocate for digital craft – the exploration of new technologies alongside existing tools and techniques.

Jo McCallum is the Founder, The Fabricated Frame – Crafting Futures, a transdisciplinary studio exploring innovation through craft. She is a Digital Craft PhD Candidate, School of Architecture, University of Queensland (formerly AHRC 3D3 Studentship in Digital Craft, based at FoAM Kernow & the University of the Arts London). Maker, Academic, and Transdisciplinary Researcher, Jo McCallum is passionate about crafting futures. Her work is focused on elevating the perception of traditional craft via making, biotech, digital fabrication, and policy development. Jo is a STEAM Ambassador and an advocate for digital craft – the exploration of new technologies alongside existing tools and techniques.