Ngaroma Riley, “Te Moko-ika-a-hikuwaru Circa 1745”, wire, Organza, shell, sequins, 500 x 500 x 250mm

Te Moko-ika-a-hiku-waru was an eight-tailed fish lizard that accompanied the Tainui waka to Aotearoa. When the waka passed up the Wai-o-taiki (Tamaki river), some of the people disembarked and settled at Tamaki. The taniwha remained with them and made its home at the entrance to what is now referred to as the Panmure Basin. The lagoon was abundant with aua(herrings), tuna(eels) and patiki(flounder) and became the feeding ground for Te Moko-ika-hiku-waru. For this reason, the spot was named Te-kai-a-Hikuwaru (the food of Hikuwaru) and was off-limits to ordinary people, which ensured a balance in ecological stability.

Wanda Gillespie is inspired by the Māori carving of the Taniwha water spirit by Ngaroma Riley, Kereama Taepa and Steve Solomon.

I first met Ngaroma Riley in 2020 at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. One of the few female woodcarvers in Aotearoa, she had found my profile on Instagram and got in touch. At the time, Ngaroma had recently returned to Aotearoa New Zealand after spending twelve years in Japan, where she first began carving through introductory workshops on Buddhist bodhisattva carving, though she was largely self-taught. Back home, she was reconnecting with her roots, studying toi whakairo (the art of Māori wood carving) at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. Her curiosity about the materials I used in my own carving practice sparked our initial conversations. She had been carving Cypress in Japan, while I often worked with locally felled ash alongside native timbers like Tōtara, Mātai, and Rātā.

Later that year, she invited me to the Te Wānanga o Aotearoa end-of-year student exhibition and a visit to their carving room. At the time, I had recently received a Creative New Zealand grant to study carving at a school in Austria. Due to the pandemic, those plans were thwarted, but I redirected the funds to online carving classes with renowned British, Russian, and American woodcarvers. I’d always thought it inappropriate for me, as Pākehā, to learn whakairo, but Ngaroma encouraged me. She explained that there had been Pākehā students before. I now contemplated how being a contemporary artist working with woodcarving in Aotearoa, it was important for me to engage with and understand this traditional craft.

Her encouragement sparked a shift in my thinking. Growing up in New Zealand, the patterns and forms of whakairo had unconsciously influenced me. I began to wonder: wasn’t it a little absurd to travel across the world to study carving when such a rich tradition was alive and accessible in my own hometown?

…carving is not just about form but about the stories embedded in each cut and pattern.

In 2022, I began studying whakairo under the skilled and generous guidance of kaiako (teacher) Cory Boyd at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. It was a gateway into te ao Māori, offering insights into the spiritual and mythical aspects of this world, as well as the distinctive carving language of whakairo.

One of the final patterns I learned was the highly decorative whakarei (surface pattern) known as Pākati or niho taniwha—the teeth of the taniwha. Composed of three incised lines (haehae) with triangular notches between them, this pattern symbolizes the protective power of the taniwha, the serpentine guardians of water and land. The technique requires precision and care, with specific chisels (a long-handled V chisel, knife and flat chisel) used in a methodical order. As I practiced, I couldn’t help but think of the taniwha themselves—beings both protective and fearsome, woven deeply into Māori mythology and ecology.

Earlier depictions of taniwha highlight their enduring significance within Māori visual culture. The taniwha Ureia, carved in the marakihau style with its serpent-like body and hollow tongue, once guarded the waters of Tīkapa (Firth of Thames). Today, this striking carving is housed in the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Similarly, the Te Motunui Epa, intricately carved panels recovered from a swamp in Taranaki, depict the serpentine Marakihau and other taniwha forms. Preserved for over 150 years and repatriated after being sold overseas, these panels now reside in Puke Ariki Museum, standing as a testament to the spiritual and ecological roles taniwha play as guardians of sacred sites and protectors of natural balance.

Te Motunui Epa, after being preserved in a swamp in Taranaki for more than 150 years and then sold on the international market, it is now home in Aotearoa, housed in Puke Ariki Museum Taranaki.

Taniwha, Marakihau, fish-tailed Manaia, Hinemoana and Tangaroa—these water spirits are not mere myths; they are active forces within te ao Māori, guardians of rivers, lakes, and oceans, and carriers of ancestral knowledge. Their presence is reflected in stories, art, and the very landscapes they protect. For instance, the purākau (legend) of Ruatepupuke tells of the origins of whakairo, where carvings were retrieved from Tangaroa’s undersea wharenui (meeting house). This story highlights the sacredness of carving—its origins intricately tied to Tangaroa, the ultimate water spirit—where each form carries profound ancestral and spiritual significance.

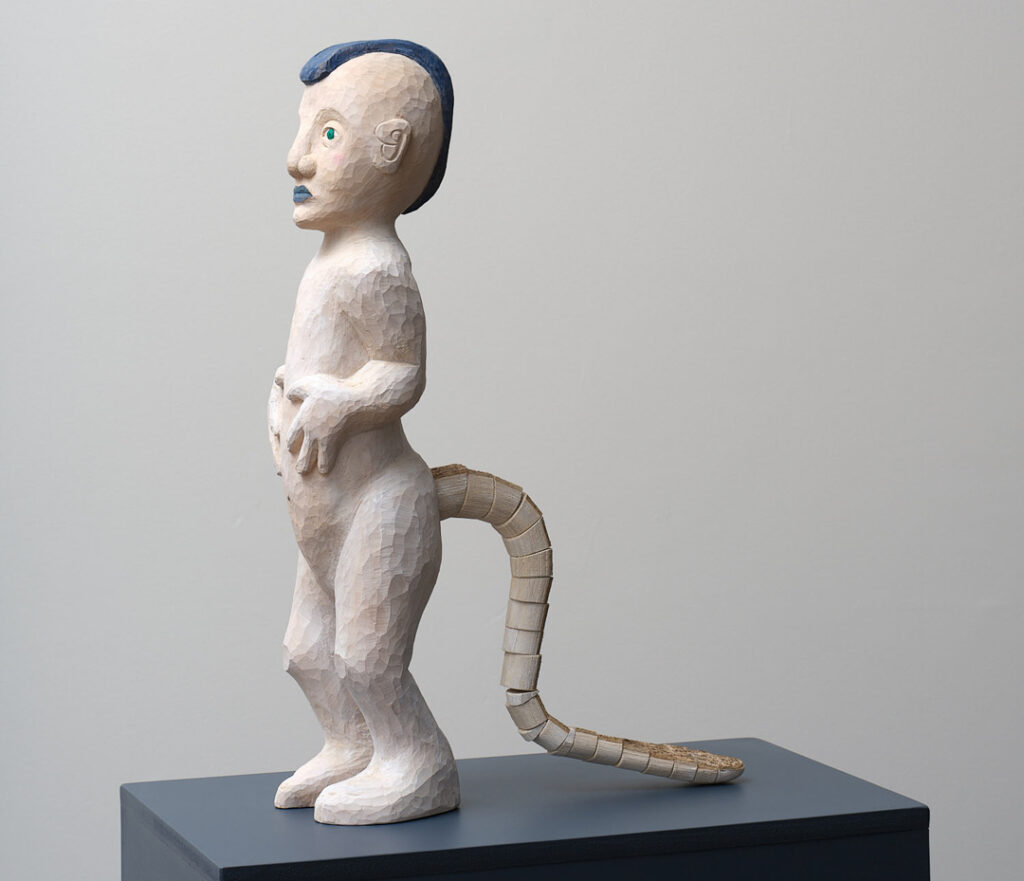

I was particularly drawn to contemporary artists who reinterpret these spiritual traditions, like Ngaroma Riley herself. Her green organza taniwha, Te Moko-ika-a-hiku-waru, references a guardian taniwha of the Panmure Basin, questioning the impact of urbanization on the environment. In another piece, she depicts Horotiu, a taniwha guardian of the Waihorotiu stream, now buried beneath Auckland’s Queen Street. Her work often intertwines spiritual, social, historical and ecological narratives. Another piece by Riley, exhibited in her recent solo exhibition at Seasons Aotearoa, reflects her whanau (family) and whakapapa (genealogy) to tūrehu, the fairy-like beings of Māori lore. The carving draws inspiration from her great-great-great-grandfather, Patana, who was said to have kept ngārara (giant lizards) the size of Komodo dragons. This sculpture, with its dragon-like tail and blue tones evoking pukepoto (blue clay), connects ancestral lore to contemporary artistry.

Ngaroma Riley, “Tūrehu”, 2024, Tōtara, whau, acrylic paint and pāua, on custom wood and acrylic plinth, 640 x 150 x 410mm (carving); 710 x 440 x 600mm (plinth); exhibited in her solo exhibition ‘Once Were Gardeners’ at Seasons Aotearoa; photo: Samuel Hartnett

Kereama Taepa, for example, uses digital technologies to reimagine traditional Māori motifs. Sea spirits with curvy serpentine forms, such as Taniwha and Manaia—spiritual messengers portrayed in profile, often with the heads of birds and the tail of a fish —appear in his tiki series, as seen in recent works at Jhana Millers Gallery.

In this series, Pākati or the niho taniwha pattern is reinterpreted with playful pop-culture references, blending ancient symbolism with modern storytelling. Instead of the traditional overlapping triangular notches symbolising the taniwha’s teeth, repeated elements like Space Invaders and Pac-Man are used, connecting the past and present. This innovative fusion breathes new life into traditional carving patterns, making them relevant and engaging for contemporary audiences.

- Kereama Taepa, “Pākitimario, Pākitipatene, Pākitilink, Pākitikari,” 2023, 3D printed nylon and pāua laminate, dimensions vary Taniwha tiki with a detail showing the space invader’s emblem used inside the lines rather than the traditional notches of the taniwha teeth. The Manaia (bird head with fishtail) seen here in green, is most often depicted as side-on in Māori carving, due to its role as a messenger between the realm of death and the living world. Manaia are not exclusively water spirits, they can be depicted as bird, serpent or human and are often used in carving to embellish and fill empty spaces around a figure.

- Kereama Taepa, “Pākitimario, Pākitipatene, Pākitilink, Pākitikari,” 2023, 3D printed nylon and pāua laminate, dimensions vary Taniwha tiki with a detail showing the space invader’s emblem used inside the lines rather than the traditional notches of the taniwha teeth. The Manaia (bird head with fishtail) seen here in green, is most often depicted as side-on in Māori carving, due to its role as a messenger between the realm of death and the living world. Manaia are not exclusively water spirits, they can be depicted as bird, serpent or human and are often used in carving to embellish and fill empty spaces around a figure.

- Kereama Taepa, “Pākitimario, Pākitipatene, Pākitilink, Pākitikari,” 2023, 3D printed nylon and pāua laminate, dimensions vary Taniwha tiki with a detail showing the space invader’s emblem used inside the lines rather than the traditional notches of the taniwha teeth. The Manaia (bird head with fishtail) seen here in green, is most often depicted as side-on in Māori carving, due to its role as a messenger between the realm of death and the living world. Manaia are not exclusively water spirits, they can be depicted as bird, serpent or human and are often used in carving to embellish and fill empty spaces around a figure.

- Kereama Taepa, “Pākitimario, Pākitipatene, Pākitilink, Pākitikari,” 2023, 3D printed nylon and pāua laminate, dimensions vary Taniwha tiki with a detail showing the space invader’s emblem used inside the lines rather than the traditional notches of the taniwha teeth. The Manaia (bird head with fishtail) seen here in green, is most often depicted as side-on in Māori carving, due to its role as a messenger between the realm of death and the living world. Manaia are not exclusively water spirits, they can be depicted as bird, serpent or human and are often used in carving to embellish and fill empty spaces around a figure.

Steve Solomon, a celebrated contemporary carver from Southland, is renowned for his precision in executing the Pākati or niho taniwha pattern. He brings the modern reinterpretation of traditional carving to public art, introducing water spirits like Manaia and Tangaroa into the public consciousness. In a recently commissioned series of pou (posts) representing the seven stars of Matariki, the Māori New Year constellation, Solomon’s work highlights his skill and innovation. One of his pou represents the star Waitā, associated with the ocean and the bounty of the sea, featuring images of whales, dolphins, penguins, and sea spirits such as Manaia and Tangaroa. These carvings symbolise the guardianship of the sea, merging traditional symbolism and decorative pattern work with contemporary public art.

- Images of work in progress from Solomons Facebook page. Niho taniwha whakarei (surface patterns) involves incised lines known as haehae with overlapping triangular notches symbolising the taniwha teeth. Steve Solomons work above is celebrated for his clean carving of this challenging pattern.

- Images of work in progress from Solomons Facebook page. Niho taniwha whakarei (surface patterns) involves incised lines known as haehae with overlapping triangular notches symbolising the taniwha teeth. Steve Solomons work above is celebrated for his clean carving of this challenging pattern.

- Steve Solomon, “Waitā”, 2024, stainless steel, laser cut

- Steve Solomon, “Waitā”, 2024, stainless steel, laser cut

As an artist who is drawn to illustrating the unseen—in the past carving spirits, subtle beings, and painting or marking wood with depictions of thought forms—studying whakairo and learning about these beings and te ao Māori has been extremely enriching. While I do not continue the exact patterns of whakairo in my own work, I have found profound inspiration and transferable aspects and techniques that have deepened my practice. Now, as I have returned to Naarm (Melbourne) to live and continue carving as an artist in residence at the Victorian Woodworkers Association workshop in North Melbourne, I reflect on what a unique privilege it was to study at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. As I carve, I think of these artists, the stories they tell, and the guardians they honour. The spiritual depth of whakairo continues to resonate, reminding me that carving is not just about form but about the stories embedded in each cut and pattern. Through my studies and practice, I’ve come to understand that the taniwha are still here, guarding and guiding us—their teeth etched into the surfaces of our art and lives. Each line and notch connect me to a tradition that is living, breathing, and evolving, much like the waters they protect.

Further reading

- Tārai Kōrero Toi : articulating a Māori design language, Witehira, Johnson Gordon Paul, 2013

- Māori Woodcarving of the Taranaki Region, Kelvin Day

- Ruatepupuke and the origin of carving

- Under the mountain

- Ureia

- Once Were Gardeners, Ngaroma Riley exhibition statement at Seasons Aotearoa

- Kereama Taepa

- Steve Solomon public sculpture Waitā

About Wanda Gillespie

Wanda Gillespie is a contemporary artist based in Naarm, specialising in wood sculpture, installation, and public art. She is currently completing a three-year artist-in-residence program at the Victorian Woodworkers Association. With a Master of Fine Arts from the Victorian College of the Arts, a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Elam School of Fine Arts, and training in Toi Whakairo from Te Wānanga o Aotearoa (Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland), Wanda’s work is deeply influenced by both traditional and modern carving techniques. Her practice, which explores themes of history, spirituality, and the intersection of value and the sacred, includes interactive abacus sculptures and figurative wood-carved works. Currently, she is preparing an exhibition at Craft Victoria, where her wood-carved and wood-turned pieces will explore prayer beads across different faiths, transforming her beads from utilitarian counters into powerful symbols of both spiritual devotion and tangible value. Follow www.wandagillespie.com

Wanda Gillespie is a contemporary artist based in Naarm, specialising in wood sculpture, installation, and public art. She is currently completing a three-year artist-in-residence program at the Victorian Woodworkers Association. With a Master of Fine Arts from the Victorian College of the Arts, a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Elam School of Fine Arts, and training in Toi Whakairo from Te Wānanga o Aotearoa (Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland), Wanda’s work is deeply influenced by both traditional and modern carving techniques. Her practice, which explores themes of history, spirituality, and the intersection of value and the sacred, includes interactive abacus sculptures and figurative wood-carved works. Currently, she is preparing an exhibition at Craft Victoria, where her wood-carved and wood-turned pieces will explore prayer beads across different faiths, transforming her beads from utilitarian counters into powerful symbols of both spiritual devotion and tangible value. Follow www.wandagillespie.com