Aram Han Sifuentes’ banners aren’t just about protest, the workshops for making them provide a rare opportunity for open dialogue between political differences.

(A message to the reader.)

Aram Han Sifuentes’s family migrated from South Korea to the USA, where her mother became a seamstress to earn a living. Aram took this childhood experience to her studies at UCLA Berkeley and the School of Art Institute in Chicago, where she developed a practice of socially engaged textiles. Sewing was the perfect medium for reflecting the lives of people like her parents.

Aram started making banners in 2015 for an exhibition about voting rights. “The project then was to speak about the millions of people who can’t legally vote in the United States, which is something that doesn’t get talked about very often.”

This quickly grew into a key part of her practice. After the Trump election in 2016, “Protests were happening everywhere.” Aram posted images of her banners on social media, which led to inquiries about how to make them. “I would just say, ‘I’m making them again tomorrow. Come to my house.’ And so people would start showing up at my house.”

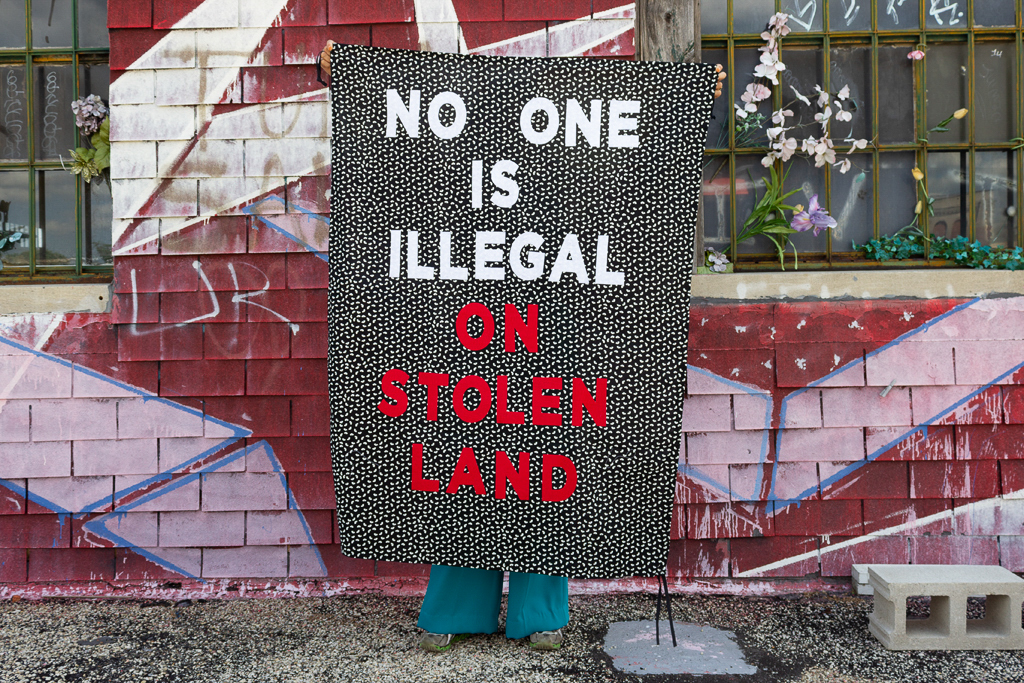

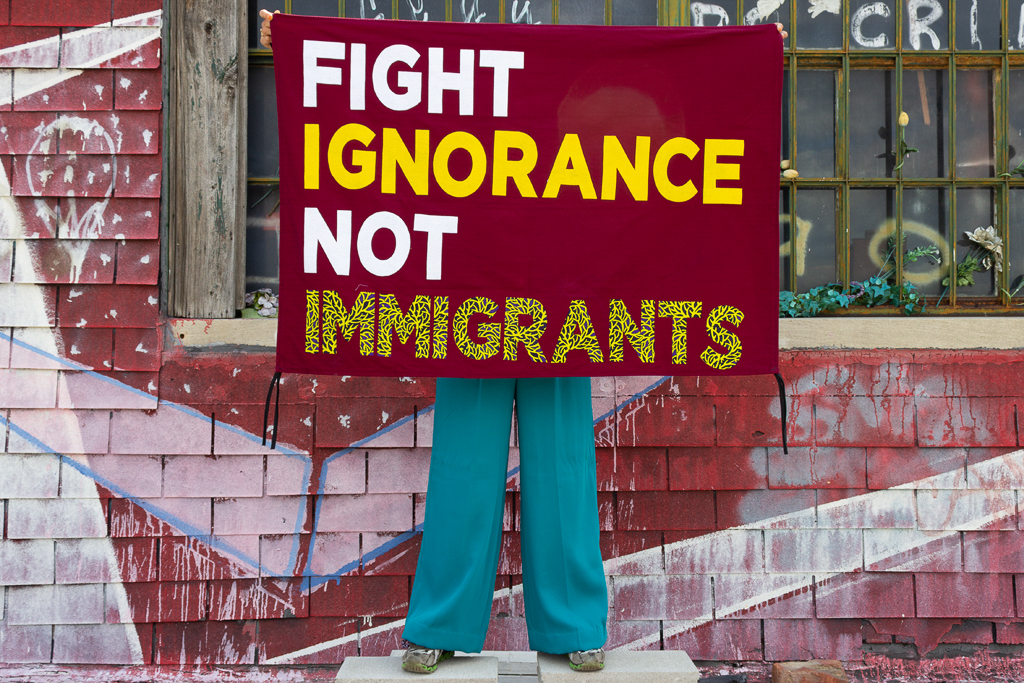

- Protest banner; photo: Bun Stout

- Protest banner; photo: Bun Stout

- Protest banner; photo: Bun Stout

- Protest banner; photo: Bun Stout

- Protest banner; photo: Bun Stout

Aram had a one-year-old child at the time who wasn’t a citizen, so she didn’t feel safe going out to protest herself, but she was more than happy to supply banners to others who could attend. “There were multiple banners that were being entrusted to me for me to check out for people to use and return to me. And so, I was like, ‘Oh, this is a lending library!'” She produced library cards with a checkout and return date, along with emails. There was also a space to share where they used the banners. “There’s no deposit. Nothing happens if you don’t return it and quite a few have never come back so maybe they’re still being used. That’s okay.”

It was self-financed at the beginning, but eventually paid workshops helped cover the costs. There have been around 3,000 banners made in the workshops. Of those, there were only around five that contained messages she didn’t agree with, like a few “All Lives Matter”. Rather than prevent them being made, Aram used the workshop is a space where differences of opinion can be safely discussed.

- Banner workshop; photo: Jessica Bingham

Aram recalls a woman who made an anti-abortion banner.

“I was helping her make the banner and I asked her, ‘Hey, what inspired this slogan? Where are you going to use it?’ And she told me how she had for years been volunteering at this organization that provides support and resources for teens who get pregnant on a low income. So she wanted to make this banner to put it in that center. And I was like, ‘That’s really kind and generous that you volunteered your time you support these.'”

The collective process of banner-making is as important as their use on the street. “That’s what I really love about the project, right? Because there are times where I am in the room with people who I don’t agree with, but we can have these conversations. And in a lot of times, it ends up being like, I can see your humanity.”

In terms of the craft, the Protest Banner Lending Library features very colourful and often comical fabrics. As not everyone has sewing skills, she uses a fusible web-like iron-on adhesive. “it’s like, ‘You just have to be able to cut and I can help you iron’, and they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, I could do that.'”

Currently, there are many protests about the invasion of Gaza. Unfortunately, opportunities for workshops have dried up because arts institutions don’t want to cause trouble. “It’s sad because many arts institutions right now would rather stay silent.”

Meanwhile, Aram has produced a series of Korean nonggi banners for an installation at Steppenwolf Theatre for a production, Sanctuary City. Through workshops, she collected stories from immigrant and BIPOC community members to tell their stories and their hopes and desires for the world.

As she writes in her Instagram post,

Nonggi have been traditionally used for diverse communal purposes and cultural activities such as festivals, gatherings and rituals. They follow the tenets of Korean shamanism to protect from evil, bring about worldly blessing and foster societal harmony. During Japanese occupation and protests fighting for Korean democracy, nonggi were used against oppression and for resistance.

The world certainly needs this kind of protection, and Aram’s humanism, more than ever.

About Aram Han Sifuentes

Aram Han Sifuentes is a fiber and social practice artist based in Chicago, who creates participatory projects that center immigrant and disenfranchised communities. Her work often revolves around skill sharing, specifically sewing techniques, to create multiethnic and intergenerational sewing circles, which become a place for empowerment, subversion, and protest. Solo exhibitions of her work have been presented at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, Chicago; Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago; Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago; Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St. Louis; moCa Cleveland, Cleveland; and Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles. She has received numerous awards including a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, 3Arts Award, 3Arts Next Level Award, Map Fund Grant, and Joyce Award. Her project Protest Banner Lending Library was a finalist for the Beazley Design Awards at the Design Museum (London, UK) in 2016. She earned her BA in Art and Latin American Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and her MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is currently a professor, adjunct, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a board member of the National Korean American Service & Education Consortium (NAKASEC) fighting for Citizenship for All 11 million undocumented immigrants and adoptees. Visit www.aramhansifuentes.com and follow @aramhansifuentes

Aram Han Sifuentes is a fiber and social practice artist based in Chicago, who creates participatory projects that center immigrant and disenfranchised communities. Her work often revolves around skill sharing, specifically sewing techniques, to create multiethnic and intergenerational sewing circles, which become a place for empowerment, subversion, and protest. Solo exhibitions of her work have been presented at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, Chicago; Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago; Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago; Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St. Louis; moCa Cleveland, Cleveland; and Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles. She has received numerous awards including a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, 3Arts Award, 3Arts Next Level Award, Map Fund Grant, and Joyce Award. Her project Protest Banner Lending Library was a finalist for the Beazley Design Awards at the Design Museum (London, UK) in 2016. She earned her BA in Art and Latin American Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and her MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is currently a professor, adjunct, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a board member of the National Korean American Service & Education Consortium (NAKASEC) fighting for Citizenship for All 11 million undocumented immigrants and adoptees. Visit www.aramhansifuentes.com and follow @aramhansifuentes