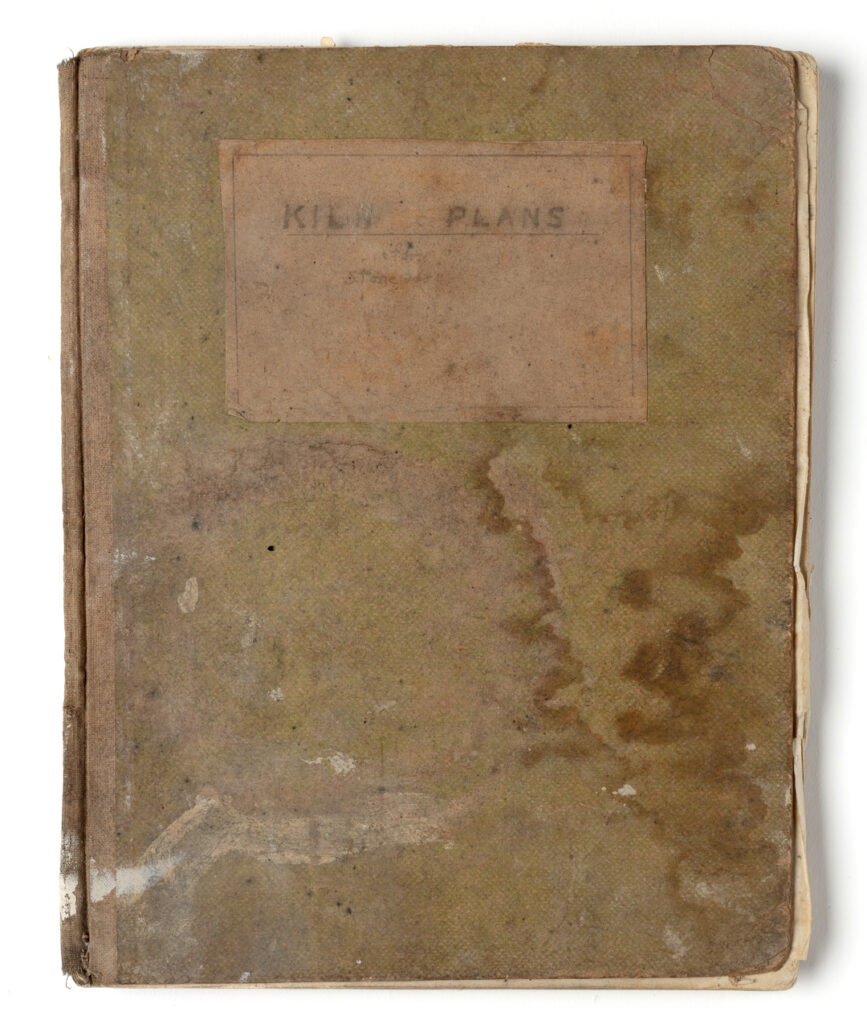

Barry Brickell, Booklet – Kiln Plans, card, paper, cloth. Barry Brickell Papers, 1965 – 1984. Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum. MS-2002-22

(A message to the reader.)

Nina Finigan celebrates the grit that accompanies the documentation of potter Barry Brickell.

The value of archival material is usually placed on its communicative abilities. Letters tell us: dates, names, places, events. Diaries reveal: observations, intimate details of people’s lives, perhaps gossip. Legers list: sales, prices, goods. We can do “serious” research with this information: this is the primary function of archives. They help us remember and place things in order: chronologies, themes, trends, changes. But what about the memory of archives themselves? Can stories be found within their physicality too?

Don’t get me wrong, of course I value the textual information that archives hold: the histories and lives that are revealed through symbols on a page. But what about their texture?

It is this|and.

Archives are witnesses. They have lives and they carry traces of those lives with them, even as they enter the stasis of a collecting repository. Indeed they hold onto those traces despite the restrictions and measures that a repository attempts to impose upon them. We are the ones who render certain aspects of an archive mute. We do this when we attempt to freeze or reverse the effects of time and activity, arresting their development and their agency. This is for good reason: we desperately want to preserve. But with this act, do we erase the lived experience of the archive?

Looking for memories within the thingness of archives requires reading them not against but through the grain. It requires listening to whispers that emerge from between cracks. One day, as I was looking through the inventory of potter, writer (or “wrerter” as he preferred), conservationist, and steam train enthusiast Barry Brickell’s archive at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum, I found myself drawn to a passage in the introduction:

“Many papers were dusty with deposits of clay on them. These have been gently brushed and dusted but when disturbed the collection continues to shed clay dust.”

The sentence is functional. It is an alert to users to exercise caution when handling the archive in this less-than-ideal state. To me, however, this sentence is not a caution but an invitation…

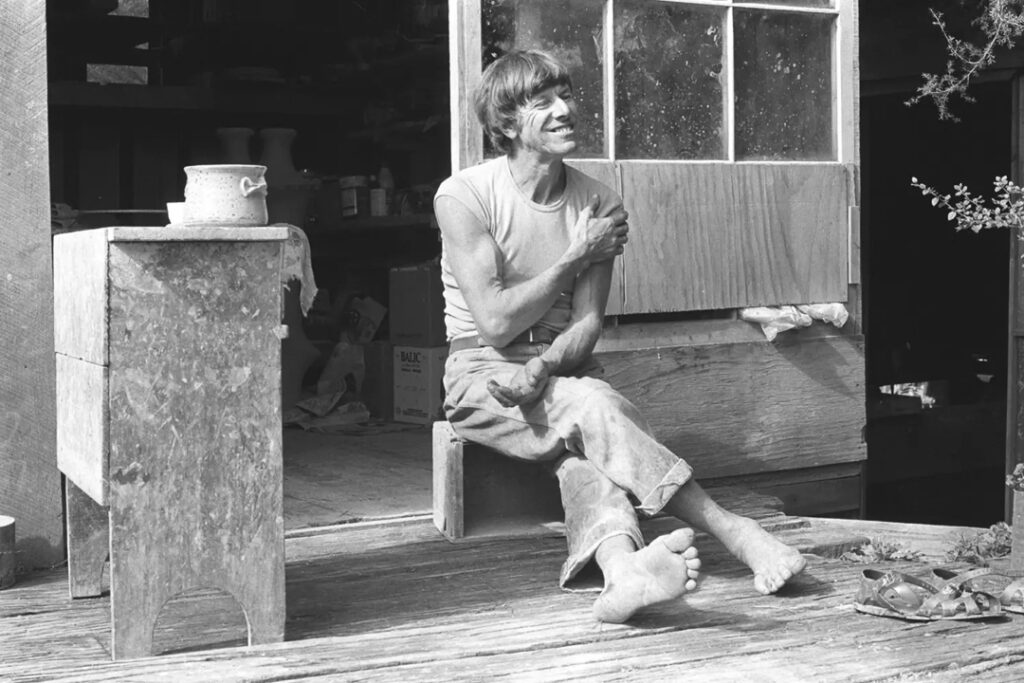

Gil Hanly, Barry Brickell, Driving Creek Railway, Coromandel, 1983, 35 mm negative, PH-2015-2-GH371-2A, Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum

Barry had a way of interacting with the world that could be described as elemental. From a young age, he was drawn to fire, smoke, fumes, and earth. The industrial spectre of Auckland’s gasworks loomed large in his boyhood. He once said, “The gas industry permeated my younger days. Every time I went to a town I headed to the gasworks” (Radio New Zealand, 2013). He would go to school smelling of fumes (Craig, 2013). Talking of school, he didn’t much like it but he did enjoy chemistry and geology. He liked earth and grimy things. He made volcanoes. “I wanted to savour the scent of smoke”, he said, “of things burning, the lick of flames – to me that was beautiful.” (Winder, no date)

The archive

Barry’s Archive arrives at the museum and we do our best to clean off its dirt. Before this, it was kept at Driving Creek, a place of clay-covered hands: of fire and soot. Where the outside was inside.

Donated to Auckland Museum in 1993, it chronicles facets of his life from the 1960s to the 1980s, and touches on his craft, his relationships with other makers, his passion for railway and steam, and the construction of his potting studio at Driving Creek, near Coromandel town.

It is arranged neatly in folders, which are stacked precisely into their boxes and ordered by type: letters with other letters, ephemera with other pieces of ephemera. The card that both the folders and the boxes are made from is archival, meaning that it is acid-free. The archive’s container will cause it no harm over the course of its life in the museum. This inertia keeps it safe. But the archive fights against the confines of this neutral pH7.0 environment. It remembers more restless places.

Klm

When disturbed the collection continues to shed clay dust.

Inside a folder named “Series 2. Correspondence and sundry papers” sits a small, green notebook. It is marked and weathered from use and exposure to the elements. A stain, edged in a darker green, creeps up the cover. Water damage. The stain looks a bit like the North Island. The edges of paper that poke out from inside the notebook have also been warped by water: “cockled” is the term conservators use. And although fuzzy the text on the notebook is legible: “KILN PLANS”.

The kiln’s breath. A long, primordial exhale.

Inside it looks like a temple. An arched, brick roof. A place to worship earth and fire.

The story goes that Barry built his first kiln at age seven in his parent’s basement and that he almost set the house on fire. Barry himself dispelled this story as an exaggeration. It was a furnace made of tins, not a kiln. Still, the dye was cast. After that incident, his mother gave him a plot in the garden where Barry could indulge himself: “Where I could do what I liked with flames and fire.” (RNZ)

Barry designed and built kilns for the rest of his life. He built them for himself. He built them for other potters. He built them in Vanuatu and Arizona. His wood-fired kiln, which he built at Driving Creek in 1974 “with bricks from the local demolished Star and Garter Hotel’s chimney,”(Driving Creek) was the first in Aotearoa that could reach stoneware temperatures.

1300 degrees Celsius. The same temperature as a hot Jupiter.

The kiln plans have been folded in half to fit in the notebook. One of these plans, dated 3rd of March 1963, retains speckles of clay dust up its right-hand side. Where the page has been dog-eared for many years, three deposits cut across the paper like crystallised mineral veins in rock.

Barry Brickell, Kiln plan, 1983, paper, ballpoint pen, pencil, clay dust. Barry Brickell papers, 1965 – 1984. Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum. MS-200

This texture is a memory

gently brushed

The lines of the kiln plan are exact. A ruler has been used to measure out each brick. On top, the dust and the fingerprints. The well-thumbed page is a palimpsest, host to an eternal conversation between the maker and the made. Symmetry in order and disorder in equal measure. “I combine all these opposites,” Barry once said, “it’s what I find exciting about what I do” (The Dowse, 2013).

This texture is text.

dusty with deposits of clay

Without words, it tells us that this piece of paper lived among others in its extended family of earthy things. And although it assumes a different form, the dust speaks the same language as the symbols on the page. Regarding his work, Barry maintained, “It’s not confined to any thing: it’s not thing-bound.” (Brickell, 1977). Boundaryless then, the hand, the paper, the drawing, the clay, the kiln are a continuous thread from mind to materiality. Given this, is there any other way for the archive to present itself? To clean its dust is to erase its memory?

In a world that is increasingly mediated through the textureless haze of a screen, let’s revel in the physicality of our archives. Let’s notice their feel, their scent, their thingness. Let’s regard them from all angles, in all lights, and understand that the unintentional traces left on them by the world are as intrinsic to their story as the intentional. A fingerprint, a smudge, a speckle. A witness.

This texture is memory.

This texture is text.

I am glad for the clay dust.

References

Winder, Virginia (no date), Earth and Fire, New Zealand House and Garden magazine. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022.

Radio New Zealand (2013), Nine to Noon: Feature Guest – Barry Brickell .

Driving Creek (no date), Our History.

Brickell, Barry (1977), The hand is more important than the brain. Art New Zealand, Issue 7, August/September/October 1977.

The Dowse Art Museum (2013), Barry Brickell: A Form of Communication.

Hura, Nadine Anne (2018), Barry Brickell – A Wrerter’s Legacy, Pantograph Punch.

Craig, David and O’Brien, Gregory (2013), ‘More Ground and in my own way’: Barry Brickell’s life work’ in Under His Own Stream: The Work of Barry Brickell.

About Nina Finigan

Nina Finigan is a curator based at Tamaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum, in Aotearoa New Zealand. Among many things, she is interested in the “embodied archive”: framing archives as spaces where bodies interact, senses mingle and coalesce, and history is three-dimensional. She is currently working on creating an archive of recipes that tell stories of movement, migration, adaptation, and resilience.

Nina Finigan is a curator based at Tamaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum, in Aotearoa New Zealand. Among many things, she is interested in the “embodied archive”: framing archives as spaces where bodies interact, senses mingle and coalesce, and history is three-dimensional. She is currently working on creating an archive of recipes that tell stories of movement, migration, adaptation, and resilience.