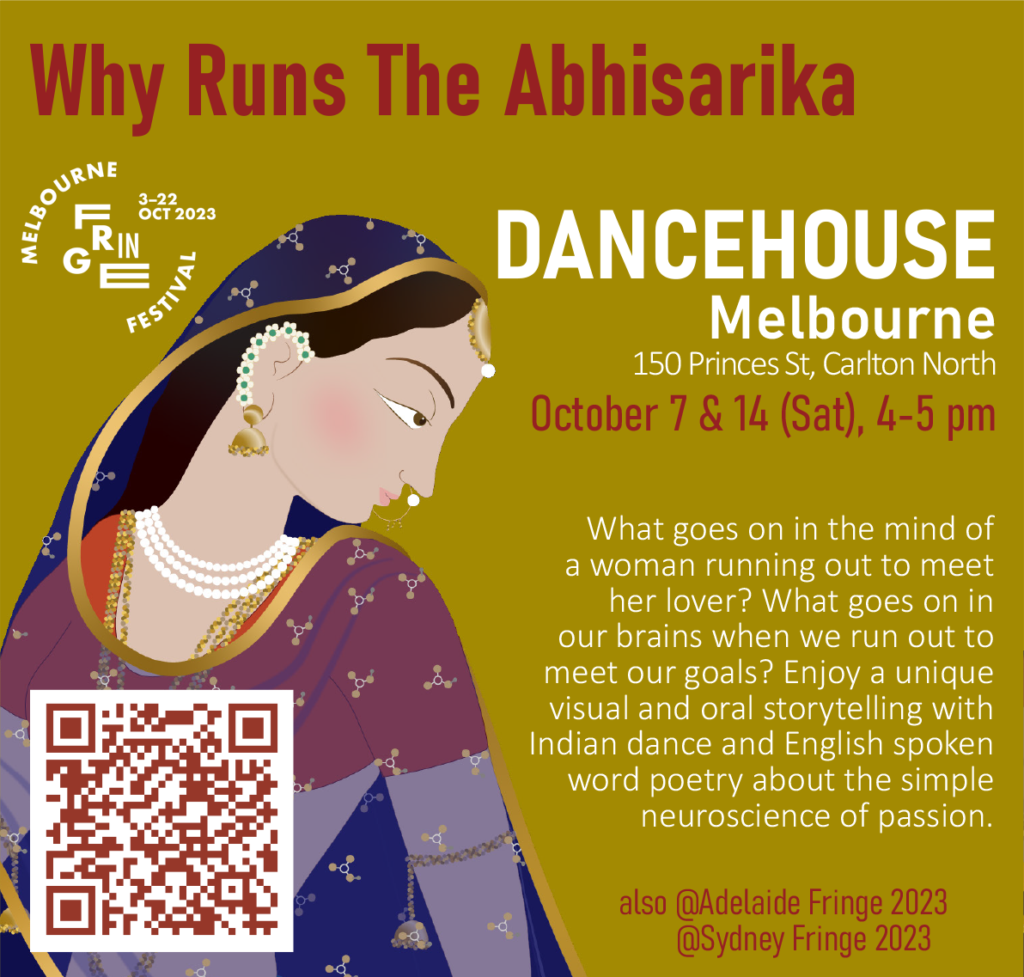

Priyanka Jain, Iconography of the Abhisarika adapted from Indian miniature paintings digital illustration, 400 x 174 cm

Priyanka Jain sings about microbes in medieval Indian miniature paintings of a love that is triggered by the smell of rain.

Petrichor is the scientific name of the smell of the earth we experience when it rains. A group of soil bacteria called Actinomycetes produce an oil called Geosmin which comes out with the air trapped in hot dry soil when cold raindrops hit the earth. This smell is alluring, drawing us out to our balconies and perhaps even drew lovers such as Abhisarika out of their homes.

In classical Indian literature, there is a detailed classification of the various phases of love and the Natyashastra (Treatise on Dramaturgy) composed in Sanskrit in the second century BCE lays out the cannons for enacting these phases of emotions. The Ashtanayika (eight heroines) personify the eight emotions expressed in the various stages of love – excitement (at the thought of meeting a lover), anxious anticipation, rage (due to the lover’s deception), jealousy, forgiveness, depression (when the lover in foreign lands), satisfaction (on being pampered by the lover’s presence) and proactively seeking out the lover instead of passively waiting for his arrival. This last emotion is assigned to the archetype heroine classified as the Abhisarika.

The Abhisarika is a determined personality. She ignores social conventions and instead of waiting at home, she moves out to seek her lover. In doing so she risks social ostracisation in the form of gossip and slander (when seen moving out during the day) and mortal fear of crossing dark snake-infested forests (when travelling at night). Many Indian miniature paintings from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century follow a fixed set of iconography to depict the Abhisarika travelling alone through a forest on a stormy, moonless night, with lightning cracking above her head, ghouls watching her and snakes coiling around tree branches. She is shown to be in such a hurry that she does not even pick up the ankle bell (a musical ornament worn on the feet) that has fallen off her feet, although she has turned her head backwards to look at it.

This iconography of the Abhisarika was rendered a new interpretation through neuroscientific lenses for a performance of storytelling titled Why Runs the Abhisarika in which the narrator plots the mental landscape of the Abhisarika as she travels in the forest. The various elements that are part of the Abhisarika’s iconography such as lightning, forest trees, snakes, ghouls, her ankle bell, etc. each offer their versions to answer why she is running in the form of songs.

To this lot of the conventional motifs as seen in Indian miniatures, I added the motif of Actinomycetes bacteria keeping in mind the recent pandemic and our newfound awareness of the powers of the invisible microscopic world around us, since the Actinomycetes would have been present in the soil two thousand years ago when the first Sanskrit poems about the Abhisarika were composed. I emphasise the vital role the smell of petrichor must have played on the Abhisarika’s mind in arousing a sudden desire to meet her lover.

Presented below is the Song of the Actinomycetes from the performance Why Runs The Abhisarika

Are you still wondering

why runs the Abhisarika out in the rain?

Well tell me then what other recourse

could actinomycetes like me choose,

not being the first to use a cloud messenger

to send news to my friends in the forest on the Abhisarika’s flesh

to come quick to picnic with me?

My letter is packed in the nitrogen of the air

whose seven electrons race across atomic space

like gracious chariot horses of the sun.

Five letters per trillion drops of rain

rise with the heat of the porous rocks

the moment a raindrop sizzles the wok

and as lovers perfume their letters with lavender

so too I smear my hand-crafted oils

of Geosmin and Tyrosine in the aerosols

that waft in the first draft of rain.

Knock knock on the olfactory nerves

Knock knock on the olfactory bulb

Knock knock in the olfactory cortex

The Abhisarika runs out to answer the door.

And when I can smell the sandalwood paste

of her breast, it is as special to me, as to you is petrichor

– the smell of mud in the first summer rain.

The rain that pours from the hemlines

of her dark cumulonimbus veils

infused with her toiletries,

and charged with electrons

from the silver sequins of her skirts

and the aurora of her ornaments

is more fertile.

The shock waves of her flying ankle bells

falling in thuds after continent-spanning strides

is more sonorous.

Flashes of her lotus feet

cutting across the dark blades of forest grass

is more brightening.

Her pearled braids snaking and rattling mid-air

with each twist of her waist

is more frightening.

I dash to greet, the corynebacterium of her feet

that can flower an Ashoka tree

I run and embrace the corynebacterium of her face

that glows like a turmeric dawn

I cuddle and squeeze the corynebacterium of

henna-stained fingertips

that can violin a lover’s waist.

Oh! What an elaborate atmospheric plot

to flavour the bland soup of the heavens with

herbs and condiments of her ointments.

For it is through me that

her frankincense will flow into the next jasmine bud.

It is through me that

her betel juice will colour the next damask rose.

It is through me that

her shellac becomes a new pomegranate seed.

For what else does nature do

but recycle and carry forward

her luggage of atoms in the vast sum of things.

Abhijit Pal, Still from performance during the Song of the Actinomycetes. (The Actinomycetes are depicted as a chain of colourful beads on the bottom left of the backdrop.)

Why Runs The Abhisarika is performed this year (2023) during the Sydney Fringe at Emerging Artist Sharehouse on September 19-23 at 7:30 pm and during the Melbourne Fringe at Dancehouse on October 7 and 14 at 4 pm. For more information visit here.

About Priyanka Jain

Priyanka Jain based in Melbourne revives Indian recitation and storytelling practices that also use a visual device in her practice-led PhD at RMIT University, Melbourne. She enjoys combining arts and sciences to create new narratives of cultural artefacts. Visit www.jainpriyanka.com, email priyankajain_85@yahoo.co.in, follow @visuoral_arts

Priyanka Jain based in Melbourne revives Indian recitation and storytelling practices that also use a visual device in her practice-led PhD at RMIT University, Melbourne. She enjoys combining arts and sciences to create new narratives of cultural artefacts. Visit www.jainpriyanka.com, email priyankajain_85@yahoo.co.in, follow @visuoral_arts