Emma Cieslik documents Vginmary’s project to re-sacralise the vulva in Poland’s religious iconography.

In 2020, Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal ruled to remove one of the exceptions—fetal abnormalities—to Poland’s law prohibiting abortion, imposing a near-total ban on abortion. This went into effect in 2021, followed by conservative laws reinforcing orthodox Catholic principles and education aimed at promoting the image of a traditional family. Like many people who could become pregnant, Vginmary, an artist based in Wrocław, Poland, felt blindsided. In response and despite facing potential persecution for creating art with religious symbols in a conservative country, Vginmary joined a continent of artists bringing the familiar figure of Mary to the streets as their own visual champion.

Vginmary is no stranger to creating Marian art. In fact, with the help of her religious parents, she has been creating religious paintings featuring Mary and Jesus for commission for years. It wasn’t until high school that she first learned about street art from a partner. He was interested in stencil art, and Vginmary created her own and pasted stickers throughout the city. She left street art until 2020 when she funneled her anger and frustration into street art. She creates her art as part of the Holy Mart project, “created as a manifesto against the current religious and political situation in Poland.”

Her art explores “what it means to be a modern woman and what it means to be in a very religious society” she explained. Those two things clashed, and artists including herself reacted to not having a significant Goddess figure within the same patriarchal religious systems that contributed to the abortion ban. Her first work of art, depicting a lightning bolt inside of an outline of Mary, represented her anger. Painted in a cold spot away from the heart of the city, Vginmary made this painting to see herself in Mary, to visualize someone who was also angry.

“I felt if there was a goddess,” she explained, “if there was someone on our side, this deity would be angry, this deity would be furious with what happened.” She drew on Christian imagery, which she admits in turn largely co-opted prior religious imagery of gods like Zeus to depict the Christian God. Mary, she believed and depicted in her art, was at war with the patriarchial gods, and embodied divine rage through that bolt.

She recalled her own frustration when creating commissioned religious art, when buyers sought a specific image of Mary. “They are really thinking about what is attractive to them, what they are pleased to look at, and during those conversations with my clients, they were expecting a very specific face.” They were seeking a cultural ideal, a Mary within whom they could see themselves. It was an ideal that does not historically exist and one that does not reflect who she is. In the same way, she does not represent herself and other individuals with vulvas within religious systems.

Vginmary’s art, however, does reference a rich artistic history. Over wine with a friend, Vginmary came to the realization that the figure of Mary herself bore a close resemblance to a vulva. At the time, she liked this visual symmetry, specifically “this representation of feminine energy and the most beautiful organ that brings life” when Polish society was regulating this organ and was offended by its imagery. Vginmary’s psychedelic Marys sought to connect Mary–a highly regulated religious figure–to something that deeply upset modern Poles.

- Vginmary, Untitled, 2022, spray paint, photo: Vginmary.

- Vginmary, Untitled, 2022, spray paint, photo: Vginmary.

The symbolism of Mary as a vulva is best seen in Vginmary’s earlier pieces, shown above, which explored the use of negative space. Photo courtesy of Vginmary.

While at the time, she created art based on her own feelings, she now realizes that her work actually reflects a Medieval art tradition involving the vulvar symbol mandorla. The mandorla has an almond shape and is drawn, painted, or sculpted around Jesus, Mary, or other religious figures. Over time, the overwhelming presence of the mandorla shifted to Jesus–his side wounds were even visualized as a mandorla. However, traditionally the mandorla represented the holy portal through which Jesus entered the world and was associated with Jesus’s mother, Mary. Vginmary didn’t initially realize she was reviving a historic tradition.

But despite her art’s historical precedence, she had to be careful to remain anonymous. Only one year earlier, Polish LGBTQ activist Elżbieta Podleśna was arrested for placing stickers and posters around St. Dominic’s Church in Plockwith images of Our Lady of Czestochowa with a rainbow halo, symbolizing the LGBTQ+ community. Podleśna, along with Anna P. and Joanna G. were responding to the homophobic decor in St. Dominic’s Church in Plock, which equated the concepts of “betrayal,” “lies,” and “hatred” with the LGBTQ+ community. In March 2021, Podleśna and two others were acquitted of the charges but the ruling was appealed. In 2022 the court found them not guilty by final judgment.

That same year, the time was right for Vginmary: the COVID-19 pandemic had just begun and most people remained cloistered in their homes. Those who did venture out had to wear masks. In 2021, she even spoke about the persecution of artists in Poland at a conference in Tromso, Norway. She also shared a small exhibition of her work at the conference but remarked honestly that this exhibition or even this discussion would not have been possible in Poland. Even this article, she noted, would not be possible.

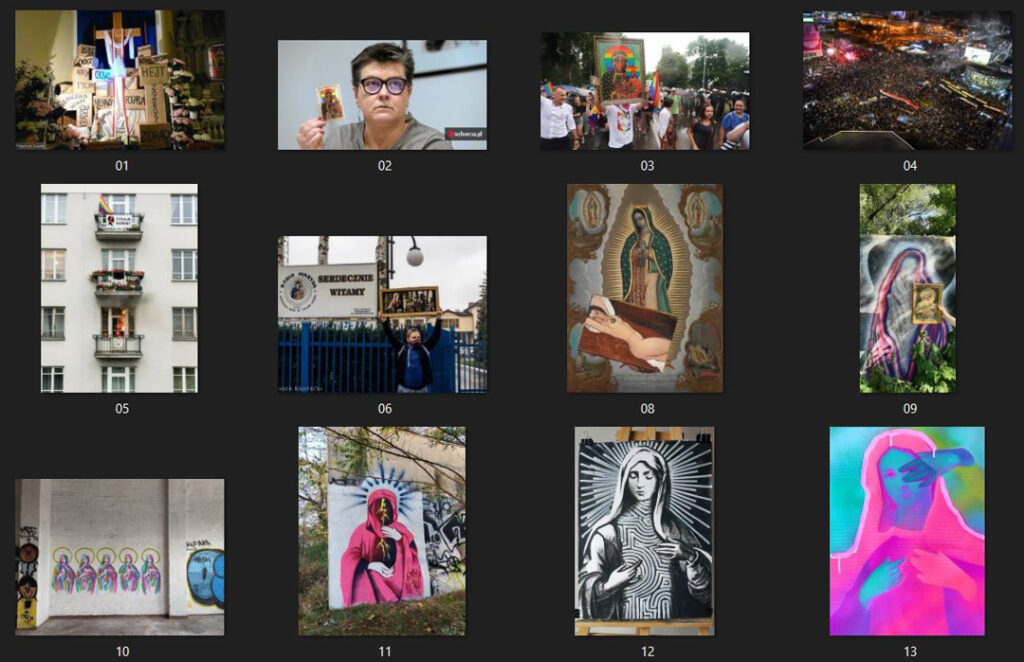

A slide from her presentation in Norway (left), and a view of four pieces she had on exhibit at the conference. Photo courtesy of Vginmary.

Even with this space and her activism, however, she still chose to largely avoid blatant political imagery or slogans. “Polish people,” she explained, “do not like to riot. Rather, they prefer guerilla methods. You’re not direct, you’re not in your face, but you’re there, and we had this during communist times with a lot of clever ways in art to portray different messages, to portray some ideas that were banned back then.” She aimed to create something that lived on the line, not over the line, so that people who are religious do not know what to do with the art, and do not see the message, but people who are facing this persecution, see it.

“I was hoping just to give a small nudge to people, like a wink maybe.” Even her religious grandmother bought and displayed one of her paintings in her home, believing it to be a traditional Marian icon.

Street art provided the freedom and accessibility to create art that walked this line. Unlike art in galleries or sanctioned murals, she did not have to submit extensive documents nor did she have to seek approval from a committee about her art’s content. She created her art on her own terms in public spaces, where people could see her art without paying an entrance fee, and where people could see the message even if there was a language barrier since all of her art involves symbolism that dates back to the Medieval Era–a time when symbols were also used to connect with faithful people who were illiterate and send messages.

In the time of the Ukranian-Russian War, she views her street art as even more significant, returning back to the Medieval tradition of pilgrims bringing vulva amulets for protection and carving vulva imagery in churches and homes to dispel evil. “I think it would be awesome to think about this imagery as a war amulet because I know that the symbol of the vagina, people thought it had this power to repel evil. If there was some disaster, like the crops were dead or there was war coming, people either showed imagery of the vagina or showed [actual] vaginas.”

- Vginmary, Untitled, 2021, spray paint, photo: Vginmary.

- Vginmary, Holy Mary of Spontaneity, 2023, spray paint, photo: Vginmary.

Two of Vginmary’s recent murals incorporate Mary into and on top of existing graffiti. The right mural was created while she worked with other graffiti artists. The silver paint was left over, which is why this piece is called Holy Mary of Spontaneity.

Her murals, painted tiles, and stickers, she believes, serve as amulets to protect against war in all forms, whether a war on reproductive rights or a war on Slavic soil. Her street art is thus an accessible, often covert form of sacred protection and rebellion in plain sight.

About Emma Cieslik

Emma Cieslik (she/her) is a queer writer and museum worker based in Washington, DC. She studies the intersection of gender, sexuality, religion, and material culture, with a focus on Marian devotions. She has been researching Marian statuettes, graffiti, and devotional art for the past year.

Emma Cieslik (she/her) is a queer writer and museum worker based in Washington, DC. She studies the intersection of gender, sexuality, religion, and material culture, with a focus on Marian devotions. She has been researching Marian statuettes, graffiti, and devotional art for the past year.

Note: The artist’s name is the same as the name of her project. Vginmary is spelled together as a type of code, where the name can be read as Virgin Mary or Vagina Mary. Like other street artists, Vginmary does not take dimensions of her work, outside of the length of arms outstretched. The nature of her work means that it does not always fit conventional artistic descriptors, including specific titles.