Ode to Waratah, hand-etched glass, steel, polypropylene, 45 x 45 x 52cm; Maker and production Luke Mills; Glass (table top) Scarlett and Brian Mellows / Aurora Glass; Photographer James Morgan; Designer Elliat Rich

Through a series of objects based on the waratah flower and its relationship to its pollinator, the honeyeater, Elliat Rich creates a mythology for understanding the poetic nature of creation.

I acknowledge that First People across the planet have and hold myths that express values of respect and reciprocity with other members of the living world and so inherently practice sustainable ways of living. As a member of the mythless, I do not claim that there is anything new in the ideas that follow, but more a way to move away from the injustices of Modernity and return, through a circuitous route, to a more Indigenous form of knowing and being. I live as a settler on the occupied Country of Arrernte people.

“Science is structured wonderment.” 1.I came across this statement somewhere in my reading, despite a lot of retracing and searching I can’t find the original author. My instinct is that it was from one of the early female scientists and came via brainpickings.com.

Throughout human history, myths have provided explanations as to how the world came to be: creation stories of gods warring to create oceans, giant animals dying, their bodies calcifying into mountains, islands that are the remnants of two ancient lovers, stories that explain the “how?” of the world. Creation stories that reaffirmed our connection to something other / more than us, mythologies that provided access to an understanding of divinity, that wove the world together, that offered moral guidance and wisdom. In the twenty-first century we, the mythless, have an explanation of the “how?” derived through scientific query to explain and (attempt to) understand the creation of the universe and the elements within it.

So, during the first second after the big bang there played out a perverse subatomic game of musical chairs, in which quarks were the players, anti-quarks were the chairs, and the winner was the one quark in a billion that couldn’t find an antiparticle chair – that left-over quark became the matter to construct our universe… 2.David Christian, Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History, 2011, University of California Press.

Using story to communicate makes scientific theory more accessible. As a broad community, we share an agreement on how the universe formed, how the Earth was made, different geological epochs, dinosaurs, dragonflies, sunsets, chlorophyll, viruses. Our scientific approach functions as our creation story—without the narrative. The difficulty is that the language, by necessity, is devoid of humanity. What we have learnt looking deep into telescopes and microscopes is explained as objectively as possible.3.I am paraphrasing wildly to say that true objectivity is impossible. Not a topic for this space, other than to say that many scientific endeavours exist within a Western-colonial worldview and reinforce that value system and as such is not immune to blind (or overt) biases. It is an eye-opening and challenging process to look back at some of our dominant scientific theories through a political / historically-present lens. For example “survival of the fittest” is not an accurate representation of functioning systems and the “competition” this theory preferences is not the primary means of survival. Collaboration is present at much, much higher rates in relationships between species. There is some stunning and deeply insightful research that addresses this, see thinking by Donna J. Haraway, Deborah Bird Rose and Lynn Margulis among many others. Scientific reasoning and language attempt to present “findings” through this lens, but this rational approach quarantines the relational and rich ambiguity that stories can hold, it removes the space to relate, interpret and derive meaning.

Designing Mythology proposes a complimentary “storying” of the science, a parallel communication method that reflects the quarks and the quantitative through narrative. That we turn a substantial and common body of knowledge, accessible and belonging to anyone, into a form that makes our cosmological framework more relatable and representative of a lifetime as a human on Earth.

The conventional scientific method separates causes from one another, it isolates each one and tests them individually in turn. Narrative, by contrast, carries multiple causes along together, it enacts connectivity. We need both methods.4.Tom Griffiths, The Humanities and an Environmentally Sustainable Australia, australianhumanitiesreview.org/2007

While most existing creation stories developed before microscopes or modern science, it is not unlikely that they share this dual insight, reflecting ‘modern discoveries’ (should a scientific lens be applied), but gleaned through centuries of continuous observation and cultural embeddedness and relationship to the land. A succinct example of this is the story of the Three Sisters learnt, held and shared through Native American tribes. While the plots vary across tribes, the premise is that the three sisters come together to support one another, that one does not function without the others. Through a botanical lens, the three plants each provide “advantages” to the others. The corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb, the leaves of the corn and beans complement each other so as to not “steal” sunlight from each other. The beans have a bacteria that lives with their roots that pull and make nitrogen available to all the plants. And the squash shades the ground reducing moisture loss, and (traditionally) had spiky spines to deter animal eaters.5.This is one of the many brilliant stories shared in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass; Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants. While I came across references to this publication throughout the development of the project it is only more recently that I have read it. It describes the premise of balancing scientific insight with traditional (or myth-based knowledge) with so much more insight and weight than I am able to capture.

All the elements for the stories that we (and the living world we are within) need are already here. We need to find ways to listen to them, speak them into being and believe what we’ve known for most of human existence. This proposal for mything our way back into the world may not be as foreign to us as we might think. For 80,000 years humans have had and practised stories that included us—humans—in the cosmology of our world. In the same way, our reptilian or primate brain still functions (think “instinct” and “reflex”), our mythological consciousness or myth brain may be a part of our cellular make-up; a muscle present, but unused. Developing over the last hundred millennia as part of our neurological makeup as we learnt language and developed culture.

It will take more minds than mine to derive and apply morality to “the science”. But this too may be found from what we learn from living systems.6.A key thesis of Kimmerer’s thinking. If we are able to recognise that our shadow metaphors are in opposition to what scientific enquiry teaches us; e.g. that all species are interdependent as opposed to a hierarchical, then perhaps it is not too much of an extrapolation to value all species as (locally specific) community members. If we could apply the tenets of biomimicry to our social organising and values, rather than only extracting the learning for technological advancement and increased comfort (for some).

The living world desperately needs us to tell stories; old and new, stories that reconnect us to kin and to this planet. Thinking, making, mything our way into relationships that will sustain each other.

Warawana Mythology – a proposal of story and objects

The stories and artefacts within the Warawana Mythology are one offering of a mythic lens to reweave ourselves into the world. At their core, they work to simultaneously undermine our “shadow metaphors” and invite in a new way of enriched and integrated thinking. The Warawana Mythology is derived from the Big Bang theory, and then follows the cosmic creation of the planet, the evolution and diversity of landforms and species, the Chicxulub impactor (the one that killed the dinosaurs) and the subsequent “reseeding” of the living planet.

Everything that is, from plants to people to protozoa, has been formed from clouds of dust and gas. This started a long time ago, and everything that has been – and will be – formed is held within Waratah.

The process of forming and reforming is empowered by Weaver. Weaver is at one time vast, acting through gravity to pull dust into suns, and also minute, riding with the bee to pollinate the flower. Every pattern you know, every pattern that is is formed and reformed again and again by Weaver.

I am, we are pattern formed by Weaver, held always by Waratah.

The design objects are odes to and earthly representations of the characters and symbols within this re-storying of the science. As objects, they provide touch-stones to a mythically scaled narrative of which we can relate to and be a part. Objects solidify common stories and provide a tangible expression of concepts that often deal with the opposite. The strength of mything is held in the combination and relation between story and object.

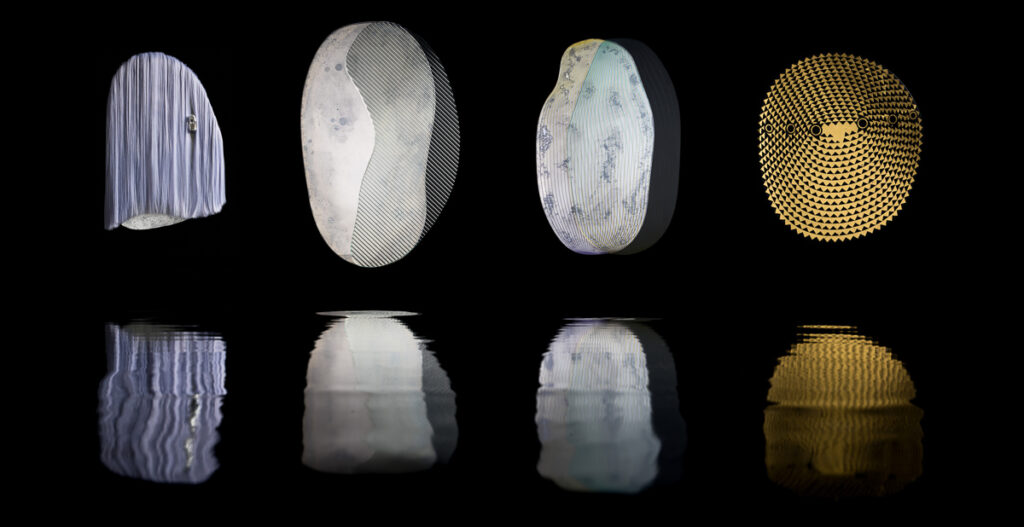

Transformation Of Weaver (artefact), Glass / silvering and production Luke Price / Outlines Architectural, Hair piece James Young, Photographer James Morgan, In-kind support The Macfarlen Fund, Designer Elliat Rich

The collection of objects includes the series of four mirrors, Transformation of Weaver; Weaver ethereal, Weaver becoming matter, Weaver patterning, Weaver earthly state/honeyeater and a side table, Ode to Waratah. The collection functions through both an industrial and mythical interpretation. Alongside the design and making of the objects a story, A basket of seeds, was commissioned (by Jennifer Mills) and an incantation written:

hoi, the waratah.

the weaver casts,

our bones warp, our breath the weft,

a pattern, the matter, our edges stretched.

I, am, we, are, held within the waratah.

Throughout the research and development of the project, there were attempts to find a way to integrate a ritual of a “living with” the objects. Contractual obligations to tell the story, annual events that recognised a time of significance, the establishment of a relationship with a local myth. The proposals were in recognition that for a myth to function it has to have a living element, something that is practised, that makes a space to remember and reflect. None of these proposals was enforced, and the project remains speculative and theoretical, although the experiment continues!7.Otherescope for Hybrid: Objects for Future Homes, MAAS and Grounding Sound (mything with kin) for Embodied Translations, Watch This Space.

Grounding Sound, a collective, synchronised, body-based, making ritual was made / practised at the end of 2020 as part of this enquiry, presented through Watch This Space

While this is an impossible project in its desire for entire living mythologies, the demand for other ways to interpret our relationship to place and each other (including more-than-humans) is imperative. Mythologies have and continue to exist and function as multi-layered mechanisms that answer the how and provide guidance and rules of engagement. Through their structure, diversity, imagination, belonging to and response to place they provide invaluable insight into other ways to structure and share knowledge and insight as humans. We, the mythless, have a common theory of creation, but our severance from humanity within this understanding leaves many of us without access to the cosmology and belonging this offers. Being a part of a cosmological narrative helps to make sense of the magnificence and mystery of our world, our fleeting moment of human consciousness.

This world was young, having just gathered itself together from dust and gas, and it was very hot and bright. Slowly, her eyes adjusted to the light. The first forms she saw were barely alive: tiny shapes, they set to work on the many small exchanges of sunlight and breath that gave air to the sky.8.Excerpt from the Warawana Mythology.

Ode to Waratah, hand-etched glass, steel, polypropylene, 45 x 45 x 52cm; Maker and production Luke Mills; Glass (table top) Scarlett and Brian Mellows / Aurora Glass; Photographer James Morgan; Designer Elliat Rich

A matter of myth

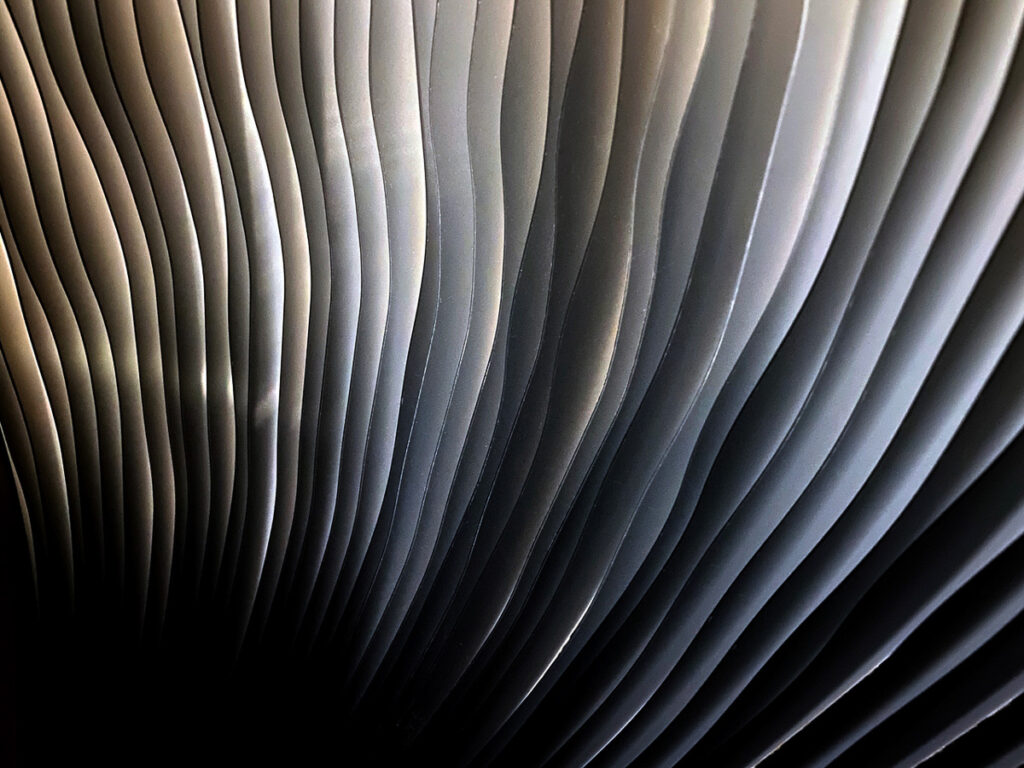

The Transformation of Weaver mirrors, made from hand-silvered glass express different states of Weaver. In Weaver becoming matter and Weaver patterning, double-layers of glass, one printed, another fluted, add movement to the object through the unpredictable refraction of light and moiré interplay of lines.

Weaver ethereal uses synthetic fibre and a glass “ear”. The sensation of tucking the “hair” behind the ear to reveal the mirror is an almost anthropomorphic experience. The looker engages through a gesture of care that imbues sentience into the otherwise static object. And Weaver earthly state/honeyeater presents the entity in a more literal form, as a bird, akin to the way we currently “see” them. As a honeyeater Weaver is a pollinator of the waratah flower, in this act they come to collect matter to weave the world as we know it. In the act of seeking self-reflection, the mirrors provide a space to remember more-than-self-connection.

Ode to waratah is a complex object that allows for layering of story and reading. The semi-translucency of the “ribs”, mushroom-like by design, play one against the other, gentle and rhythmic to run your hand along. A mesmerising pattern is hand-etched onto the glass top, illustrating the concept of the planet as a basket holding all matter. Without clear scale, only vaguely topological, the side table of glass, steel and plastic is perhaps a little on the heavy side to evoke a woven basket, but then the matter of the Earth is ancient and heavy enough to create its own gravity.

Waratah as a symbol of the basket of matter, a planetary sphere whose molecules came together in deep space to form an ever-changing almost impossible-awe-inspiring living planet.

The collection was first published through Sophie Gannon Gallery during Melbourne Design Week 2020.

Glossary

Mythless: those who live by and have an understanding of themselves as separate from the living systems of the planet. Those who continue to value conceptual ideas which are removed from the Earth as being superior to the Earth.

Shadow metaphors: unarticulated concepts that developed through, and sit at the core of the Western-colonial value system e.g.

- Scala Natura, the belief that men are of more value/closer to God than animal, plant or mineral.

- The binary, that there is a clear delineation between “opposites”; good and bad, man and woman.

- Nature as Machine, the belief that living systems can be broken down into their “parts” and understood and controlled. This denies the multiplicity of inter-relational dependency of all living systems.

- Possibly a combination of the above is the construct of linear time as well as the dismissal of ways of being that don’t follow the same value systems.

Warawana: Composite word derived from waratah, an endemic genus of five species native to the southeastern parts of Australia, and Gondwana, the ancient supercontinent.

Western-colonialism: a political-economic-cultural project, beginning in the sixteenth century, when various European nations explored, conquered, settled, and exploited large areas of the world for the benefit of themselves and/or their nation-state. Capitalism is the main mechanism for this ongoing phenomena.

World, Earth, planet: are used interchangeably to describe the ongoing exchange of matter and energy created through the sympoietic systems unique to this planet. NB: this is not limited to common categorisations of what is ‘alive’ or sentient (animals, plants, bacteria), and isn’t alive (weather systems, land formations, oceans, skies), but inclusive of all and that in between.

About Elliat Rich

For Elliat Rich the design process is a creative translation between materials and culture, alive to a broader context of power and social value, always calling on the possibilities of the imagination. Her designs function as periscopes peering around the edges of Modernity to get a better look at our almost-impossible-awe-inspiring planet. Elliat is based in Alice Springs, on Arrernte Country, mostly Mparntwe – Central Australia. She works across a broad spectrum of design for a diverse client base, remotely, locally and nationally. Her practice covers cross-cultural resources, exhibition design, public art and furniture, product development, one-off exhibition and editioned objects. All projects align with an ethical imperative to increase equality between people and across species, now and into the future. Visit gentlymythic.com and follow @elliatrich.

For Elliat Rich the design process is a creative translation between materials and culture, alive to a broader context of power and social value, always calling on the possibilities of the imagination. Her designs function as periscopes peering around the edges of Modernity to get a better look at our almost-impossible-awe-inspiring planet. Elliat is based in Alice Springs, on Arrernte Country, mostly Mparntwe – Central Australia. She works across a broad spectrum of design for a diverse client base, remotely, locally and nationally. Her practice covers cross-cultural resources, exhibition design, public art and furniture, product development, one-off exhibition and editioned objects. All projects align with an ethical imperative to increase equality between people and across species, now and into the future. Visit gentlymythic.com and follow @elliatrich.

Related stories

References

| ↑1 | I came across this statement somewhere in my reading, despite a lot of retracing and searching I can’t find the original author. My instinct is that it was from one of the early female scientists and came via brainpickings.com. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | David Christian, Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History, 2011, University of California Press. |

| ↑3 | I am paraphrasing wildly to say that true objectivity is impossible. Not a topic for this space, other than to say that many scientific endeavours exist within a Western-colonial worldview and reinforce that value system and as such is not immune to blind (or overt) biases. It is an eye-opening and challenging process to look back at some of our dominant scientific theories through a political / historically-present lens. For example “survival of the fittest” is not an accurate representation of functioning systems and the “competition” this theory preferences is not the primary means of survival. Collaboration is present at much, much higher rates in relationships between species. There is some stunning and deeply insightful research that addresses this, see thinking by Donna J. Haraway, Deborah Bird Rose and Lynn Margulis among many others. |

| ↑4 | Tom Griffiths, The Humanities and an Environmentally Sustainable Australia, australianhumanitiesreview.org/2007 |

| ↑5 | This is one of the many brilliant stories shared in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass; Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants. While I came across references to this publication throughout the development of the project it is only more recently that I have read it. It describes the premise of balancing scientific insight with traditional (or myth-based knowledge) with so much more insight and weight than I am able to capture. |

| ↑6 | A key thesis of Kimmerer’s thinking. |

| ↑7 | Otherescope for Hybrid: Objects for Future Homes, MAAS and Grounding Sound (mything with kin) for Embodied Translations, Watch This Space. |

| ↑8 | Excerpt from the Warawana Mythology. |

Comments

Loved reading your article Elliat….and “the mythless” stuck in my head.