Boteh – gol badam – kerii – paisley

What should we call this pattern?

Ancient Persia called it boteh, which means a shrub with a cluster of leaves. Then later became known as buta almond or bud.

Paisley was the name of a town in southwestern Scotland. “Paisley” derives from the Celtic word passeleg which means ‘basilica’ indicating a major church.

French at one point called it “tadpole,” the Viennese, “little onion.” The United States term among quilt-makers was Persian pickles. The Welsh textile industry called it Welsh pears.

Here are the names we know: ambi – mango (Punjabi), boteh – flower (Ancient Persia), buta – almond (Ancient Azerbaijan), gol badam- flower (Afghanistan), kajoo phal – cashew fruit (India), kalka – mango (Bengali), kerii – mango (India/Hindu/Urdu), khajoor – date palm (India), koyari- mango seed (Marathi), mamidi pinde – young mango pattern (Telugu), mankolam – mango pattern (Tamil), motif cachemire – shawl/ tie/ pattern (France), paisley – basilica (Ancient Celtic), têtard – tadpole (France), türkishces Muster – patterned shirt (Germany).

What does it mean?

“It has many symbolic and cultural connotations which vary globally. The way in which symbols from different cultures appear in the development of the paisley pattern show how weavers translated artistic influences from imported ceramics, documents, fabrics into their own designs.” Patrick Moriarty

The original Persian droplet-like motif—the boteh or buta—is thought to have been a representation of a floral spray combined with a cypress tree, a symbol of life and eternity. The seed-like shape is also thought to represent fertility and has connections with Hinduism. It also bears a resemblance to the famous yin-yang symbol used in ancient Chinese medicine and philosophy.

For Middle Eastern customers, the curved geometric paisley shape as we know it today was widely used. This was partly due to the Islamic preference not to depict recognizable natural objects. The Buta shape is the national symbol of Azerbaijan to this day, it symbolizes fire and is most commonly seen on their bright intricate woven carpets and rugs.

In India, it represents many objects including a cashew fruit, a mango or a sprouting date palm, many of which are Indian symbols of fertility.

It is still a hugely popular motif in Iran and South and Central Asian countries and is used for weddings and other celebrations. “Throughout the decades, paisley has always been a popular print for men’s ties. I’ve always found it intriguing that a design that is purported to derive from Indian fertility symbols has always been prevalent on an item of clothing that, by its very nature, acts as an arrow pointing down the torso of its wearer to his groin.” Jeremy Langmead

Tracking its progression through time

The Paisley pattern can be traced back to Ancient Persia and Indo-European cultures, 2000 years ago. It also had roots in Celtic art but died out under Roman influence. The motif continued in India and flourished to different art forms, around the fifteenth and sixteenth century where the first use of this pattern on shawls was made in Kashmir. Many travellers, mostly European and from the East India Company who came to India returned to Europe with a paisley patterned shawl, around 1775, mid-eighteenth century.

From around 1790- 1870, these shawls became the fashion for rich and stylish women, but were short in supply and very expensive. It was then that Europe started creating their own weaving shops and productions. There was such a demand for it that a town in Scotland was named after it due to it being the epicentre for weaving these shawls. In the Victorian era, trade between Britain and India was quickly expanded thanks largely to a paisley-orientated collection, a “dialogue” between eastern and western cultures and “It was a cultural exchange, and also an industry.” (Dennie Nothdruft).

The fall in popularity of paisley in 1870 was due to the complete halt of exports from Kashmir and so people started imitating the print using cheaper materials in Europe. Once it became so inexpensive that anyone could wear it, the demand for it died out.

The cypress tree in Persian poetry

“He was like a tall cypress tree topped by the full moon, and the royal farr shone from him.” Ferdowsi, The Reign of Kayumars, Shahnameh (The First Kings), 977 CE.

In Daqiqi’s account, the spirit of Zoroaster is metaphorically connected with a great tree, bearing the immortal fruit of wisdom, with many branches spread far and wide:

- “Its leafage precepts and its fruitage wisdom. How shall the one die who has eaten such a fruit? A tree right fortunate and named Zoroaster, who cleansed the world from evil deeds”, – (S V:79–80)

- “He wrote on the tall cypress tree: “Goshtāsp has accepted the good religion.” He made the noble cypress witness that wisdom was disseminating justice”. (S V: 82)

- “Trust in the shadow of this cypress tree”, (S V:83–84)

Thanks to Aishah David for compiling this research.

✿

The cypress tree ✿ Where paisley began - The popular Western paisley pattern has evolved over many generations from its root in the cypress tree, a Persian symbol of eternal life.

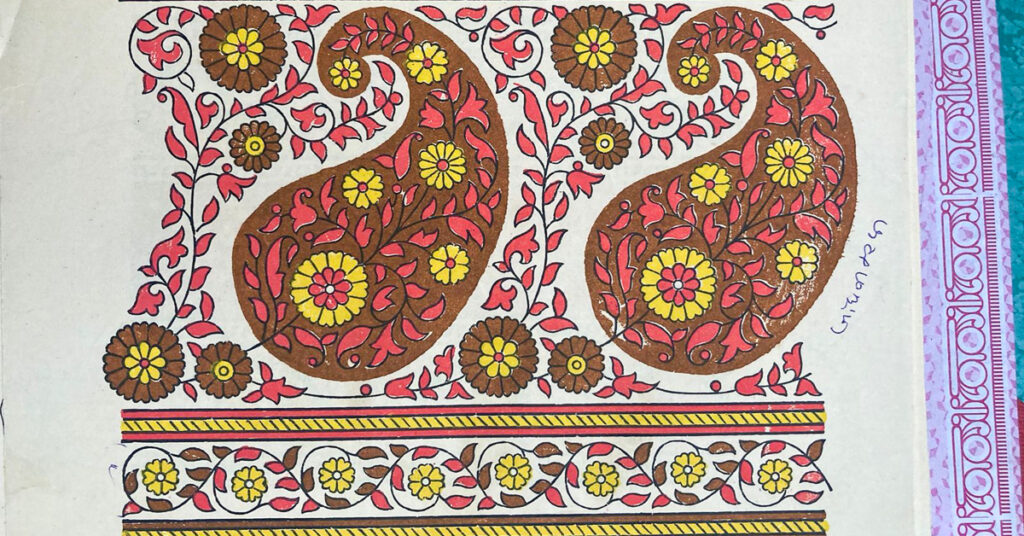

The cypress tree ✿ Where paisley began - The popular Western paisley pattern has evolved over many generations from its root in the cypress tree, a Persian symbol of eternal life. Govindbhai ✿ Keri classic - LOkesh Ghai presents a keri motif, a Western Indian version of paisley, by master block carver, Govindbhai.

Govindbhai ✿ Keri classic - LOkesh Ghai presents a keri motif, a Western Indian version of paisley, by master block carver, Govindbhai. Pashmina: A perennial luxury - Khushbu Mathur reflects on the enduring appeal of the Kashmiri shawls made from the wool of the Himalayan Ibex.

Pashmina: A perennial luxury - Khushbu Mathur reflects on the enduring appeal of the Kashmiri shawls made from the wool of the Himalayan Ibex. The time-honored Ashavali brocades of Gujarat - Vishu Arora finds a workshop in Gujarat India that is successfully continuing a textile tradition more than 500 years old, thanks to the magical waters of Lake Kankariya.

The time-honored Ashavali brocades of Gujarat - Vishu Arora finds a workshop in Gujarat India that is successfully continuing a textile tradition more than 500 years old, thanks to the magical waters of Lake Kankariya.  Spinning a Yarn Unparalleled - Gopika Nath reviews Saiful Islam's history of muslin. She finds it a compelling and epic account of the extraordinary skill involved in this lightest of textiles, as well as a tragic tale of the damage that came with British colonisation.

Spinning a Yarn Unparalleled - Gopika Nath reviews Saiful Islam's history of muslin. She finds it a compelling and epic account of the extraordinary skill involved in this lightest of textiles, as well as a tragic tale of the damage that came with British colonisation. Paisley stands tall again: Akhtar Ismailzadeh’s patteh embroidery - Ansie van der Walt writes about the patteh embroidery of Akhtar Ismailzadeh, an Iranian migrant living in South Australia. The paisley is sometimes inteprets as the cyprus tree which has been bent by the hardships of exile. Akhtar's work corrects this by straightening the paisley again.

Paisley stands tall again: Akhtar Ismailzadeh’s patteh embroidery - Ansie van der Walt writes about the patteh embroidery of Akhtar Ismailzadeh, an Iranian migrant living in South Australia. The paisley is sometimes inteprets as the cyprus tree which has been bent by the hardships of exile. Akhtar's work corrects this by straightening the paisley again. With the tip of a needle - Melinda Rackham looks into the Guildhouse Traditional Crafts program, and finds how some migrants to Australia are building new lives for themselves from the craft skills they brought with them.

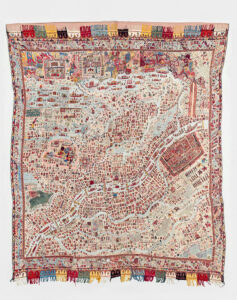

With the tip of a needle - Melinda Rackham looks into the Guildhouse Traditional Crafts program, and finds how some migrants to Australia are building new lives for themselves from the craft skills they brought with them. FRACTURE – show on textiles at the Devi Art Foundation - Between January and May 2015, The Devi Art Foundation in Gurgaon hosted an important exhibition of textiles FRACTURE, which featured some monumental works demonstrating the creative power of Indian craft and art. Co-curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul describes five of the works.

FRACTURE – show on textiles at the Devi Art Foundation - Between January and May 2015, The Devi Art Foundation in Gurgaon hosted an important exhibition of textiles FRACTURE, which featured some monumental works demonstrating the creative power of Indian craft and art. Co-curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul describes five of the works.