- pg 125 French ladies in fine muslin Wearing muslin became the rage in France and these two ladies are showing off their dresses. Courtesy of hand painting from the 19th century, Drik Collection.

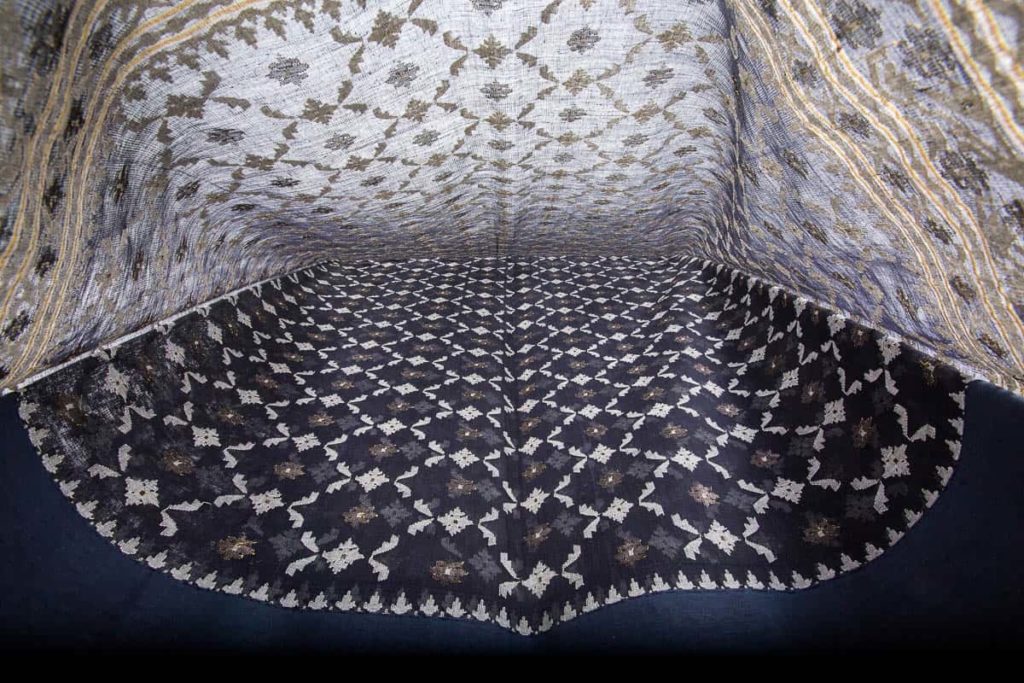

- pg 182 Jamdani sari by Haji Kafiluddin captures timeless motifs. A jamdani sari by master weaver Haji Kafiluddin billows out, reminding us of their unique centuries-old designs. Photo: Habibul Haque , Drik. Courtesy of Ruby Ghuznavi.

- Painting of Gossypium arboreum. Painting of Gossypium arboreum in Kolkata herbarium archives by unknown artist, commissioned by William Roxburgh (1751-1815), acknowledged to be ‘father of Indian botany.’ Photo: Shahidul Alam, Drik. Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden, Kolkatta, India.

- pg 97 Indian muslin weavers. Indian muslin weavers, outside their thatched houses, busy with final processing of the fabric. Reproduction from postcard, Photographer : Unknown

- 3. Fig. 66 – Turkish man wearing muslin turban (Title) Turkish man donning muslin turban. The fabric was favoured for turbans and worn in different styles by the Sultan and many Ottoman officials (Detail) Photograph of painting in Topkapi Museum, Istanbul, Turkey (taken by Saiful Islam)

- pg Al-Amin, weaving age-old motifs on the loom, Bangladesh (Title) Master weaver Al-Amin of Rupganj, Bangladesh weaving ‘new muslin’ sari using high count threads of today. (Detail) Shahidul Alam, Drik (Photo Credit)

- pg 209 A kandul catches the light on the loom A kandul lies on the loom, taking a break from its exertions Photo: Tapash Paul, Drik.

A review of Saiful Islam Muslin—Our Story (Drik Picture Library Ltd., 2016, 155 pages, full colour, ISBN 978-984-34-0013-0) see extract.

A legendary fabric, muslin, has legions of tales in its telling. This ultrafine cotton cloth from the phuti karpas and now extinct gosspypium arboreum plant, woven on the humble pit looms of Bengal, captivated the imagination of poets and fashionistas for millennia. Few fabrics in the world have acquired and retained such mystique. It inspired weavers in Europe to copy its elaborate processes leading to a mechanised version which spelled a death knell for indigenous craftsman who’d spun and shuttled a fabric, likened to “woven air” and “the skin of the moon”. Muslin pyjamas, teamed with costly pearls and rubies, emphasised the understated elegance and symbolic simplicity of Mughal emperors. A diaphanous fabric so fragile, it was reputed to last only one night of wear—Aurangzeb chided his daughter for appearing nude when she was actually draped in seven layers of it. Thumbs were said to have been cut off to prevent Bengal’s weavers and spinners from making the superfine fabric, giving England a monopoly in trade. And Napolean is said to have torn the dresses off Josephine and her daughters if suspecting that the muslin was made by his archenemy.

In an impassioned quest, Saiful Islam takes us along Bharmaputra’s watery bends to Mymensingh as “the orange orb sinks like a fire below the shimmering surface of Sitalakhya”. Travelling forty miles along the meandering river’s unique typography, geology and climatic character, he takes us into the homes of weavers and into grand Mughal palaces as he listens to ghazals and the whispers of conspiracy, envisioning the furrowed brow of hapless farmers when the taxmen knocked at their doors. The famine of Bengal with its “gnawing hunger in a starving child’s belly and crack of rifle”, fired by people serving colonial masters, become subplots in the uncovering of the story of muslin. It is the story of undivided Bengal and the “white gold” that became the fabric of intrigue, grisly politics and poetic fashion espoused by Jane Austen, Marie Antoinette and countless women across time.

The book begins with a search for the plant, continues with the evolution of cotton from agricultural crop to fashion garments, leading to the secret behind “Bengal’s Genius”—narrating details of the process involved in the making of muslin which spanned many stages, of which the most vital was spinning. In the Bardhaman District of West Bengal, India, Islam meets Jyotish Debnath, a legendary craftsman who spearheaded the national craft council’s project to revive the spinning of fine 300-500 count yarn to supply weavers of Jamdani. Discovering common family roots in the Naakhali district of Bangladesh, he persuades a reluctant Debnath to demonstrate. I read with untold anticipation as Saiful Islam, acutely aware that he has possibly met “the last in a venerable line of Bengali spinning masters”, described the time-worn technique.

A sub-chapter is devoted to “Crafting Muslin” which delineates all processes from Shuta Natan – winding and preparing the yarn, Tana Hotan—warping, Shana Bandha—applying warp to reed, Narod Bandha—applying warp to end of roll loom, Bu Bandha—preparing heddles, Kapor Bunon—weaving on the loom and Dhoper Kaj—steam washing. Also included are the auxiliary processes and people involved in this from the Nurdeeahs, who stretch cloth on the wooden frame and lightly brush with comb-like leaf to get yarns that were dislodged during washing into place; the Rafugers who repair the cloth damaged during bleaching; Dagh dhobees, the Koondegur who made the muslin smooth using conch shells or a small wooden hammer to even out crinkles, Istreewalas, the Puttoah or dyers, and the Bustabund who tied the bales.

Visiting museums across the world from the Victoria and Albert to the Louvre and Crafts Museum in Delhi in search of facts and stories, the author is candid in his disappointment with Glasgow and Paisley, where he finds no mention of Bengal in the history of muslin and one senses the urge to tell the story of Bengal emerging with greater conviction. He meets many people on his quest and we are not precluded from any part of this journey steeped in a silent grieving for irreparable loss, voiced through the lament of an elderly man from Kishoreganj in North Dhaka who said “I have heard that there was a time you couldn’t sleep because of the sound of looms and shuttles. But it is all over. We can’t even remember the last time somebody wove.”

Saiful Islam attempts to unravel the reason for its extinction, telling us how the plant that created a fabric whose trade fuelled riches, shaping the dreams of agents and sellers from Greek merchants to Arabs, Chinese, Persian, Armenian, Portuguese, Dutch, French traders and the East India Company, went into non-existence—not because it was unworthy of time, but because of greed and pursuit of power. In narrating the story of the fibre, its warp and weft unravels the history of crafting in the subcontinent, telling us that in Chandragupta Maurya’s reign [322-298BCE] craftsmen were given special protection by the king and craft guilds had their own courts for maintaining discipline and quality. The Mughals introduced the Karkhanas, a manufacturing system brought in from Persia. Although free trade of cloth was restricted, the governance of the Mughals had “humane and just laws”. This gave way to a coercion based system of production and procurement adopted by the East India Company, who passed legislatures that snared non-literate weavers into a costly, time-consuming web of litigation, perpetuated from generation to generation.

The book is a labour of love that has been written, not by a textile historian, but a man who wanted to fully understand Bengal’s supreme craft and the “cloth-smith’s ultimate gift to a craving world.” He shows us how difficult it was to construct its history by taking us along a journey that reads as much as a personal travelogue as also a thoroughly research volume, worthy of any historian. Tracing muslin’s genealogy, he steps backward in time through fragile reminisces from contemporary weavers and unsubstantiated legends that have captivated the world’s imagination. Hoping to find someone who had seen the mosrin tula gaach (fine cotton plant), the author distributed images of the muslin plant in village homes, tea-shops and markets, listening patiently to “old whispers” and “half-stories” that “quickly unravelled as fragile memories tied by fraying threads of oral tradition.” His narration is captivating to read, for alongside facts and figures are stories within stories that place the “glossy, feather-light, transparent cotton” fabric, its wearers and makers within delicate folds, not unlike the fabric itself which was packed into snuff boxes when gifted to Madame de Pompadour.

In a complex web that spans millennia, Muslin—Our Story, reveals, uncovers and re-states the fragile nature of handcrafting in an industrialized world. Although “our story” is cited as the East Bengal, now Bangladesh, story of a cotton plant that was nurtured by the fertile plains of the Brahamaputra—a story that came to a close in the nineteenth century, I see it as the story of disempowerment within the ambit of mechanisation and a story equally relevant today, across frontiers, where work with the hand cannot compete with machines and digitized technologies. This story is a tale of innocence trampled by greed, excellence requisitioned by power and best summed up in a letter published in 1828 in a Bengali newspaper Samachar Darpan, where a spinner laments the decline of trade and income:

“I am a spinner. After having suffered a great deal I am writing this letter…the weavers used to visit our houses and buy the charkha yarn at three tolas per rupee.

“Now for 3 years we two women, mother-in-law and I, are in want of food. The weavers do not call at the house for buying yarn. Not only this, if the yarn is sent to market, it is not sold even at 1/4th the old prices…..They say that bilati yarn is being largely imported…I heard that its prices is Rs.3 or Rs 4 per seer, I beat my brow and said ‘Oh God, there are sisters more distressed even than I. I had thought that all the bilati were rich, but now I see that there are women there who are poorer than I…..they have sent the product of so much toil out here because they could not sell it there. But it has brought our ruin only. Men cannot use the cloth of this yarn for even two months; it rots away. I therefore entreat spinners over there….to judge whether it is fair to send yarn here or not.”

Saiful Islam is careful not to point fingers and notes that the decline of muslin was not the result of one fatal blow, from a single quarter, but “was the combination of an opportunistic extraction system that pre-dated the English—which was maximised, refined and institutionalised during their regime, compounded by famine and other calamities. Ultimately it was mechanisation that swept away this vast, weakened, fragile rural network of artisans and their support structures.”

It is a seminal volume that will not only grace the shelves of a discerning library, but is a must read for anyone who has ever loved Indian textiles, however brief the affair. Because, in the vast and glorious history of Indian textiles, there has never been fabric as translucent, as fragile, as skilfully woven as the plain, unembellished muslin, which Saiful Islam tells us, most emphatically, does not draw its origins or name from Mosul in Iraq, but has its roots deeply embedded in the history and psyche of the Bay of Bengal.

Author

For Gopika Nath, thread is a metaphor for living. A Fulbright Scholar and alumnus of Central St. Martins School of Art and Design [UK], Gopika Nath is also an art critic, blogger, poet and teacher who lives and works in Gurgaon, India. Passionate abPassionate about textiles, she is evolving a contemporary language of thread, through the art of embroidery. You can read her Quarterly Essay on phulkari here.

For Gopika Nath, thread is a metaphor for living. A Fulbright Scholar and alumnus of Central St. Martins School of Art and Design [UK], Gopika Nath is also an art critic, blogger, poet and teacher who lives and works in Gurgaon, India. Passionate abPassionate about textiles, she is evolving a contemporary language of thread, through the art of embroidery. You can read her Quarterly Essay on phulkari here.

Comments

NICE !

Loved it; cover to cover!

Love the feel!!!