Ro Cook has been a Sydney textile artist for twenty years, following a long career working in film and television. Mark Stiles interviewed her as she was finishing work for her exhibition Absent Friends at the Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby, in June 2018.

Q : Your exhibition is based on two big themes, death and friendship, not normally treated together. What gave you the idea to do this?

A : I think we’re not very good at dealing with death in the West. They do this much better in other cultures, where they allow a longer time to grieve. We’ve homogenised the whole process so that we seem to have less and less time to respond to someone’s death. The exhibition is a celebration of twenty-four people I’ve known, some family, some friends, whose memory I cherish. The pieces are offerings to them sometimes long after the event in a way that I hope is much more positive than melancholy. They represent a continuing relationship, a friendship that is not over.

Q : There’s a strong emphasis on the handmade in the show.

A : Yes, the pieces are also a reaction to the increasing use of technology in our lives. Even in my career in film and television there was a growing use of things like special effects that seems to have taken over now. My work is not perfect and definitely not shiny. They are simple pieces with strong stories behind them, connected to real people, that allow audiences a more direct response to the work. I hope the pieces will prompt the audience to consider the relationship with their own absent friends.

Q : You’ve used handwoven hemp as the basis for each piece…

A : I’d been using hemp for a while as a fabric and really liked it, both as a material and because of my interest in sustainable fashion. I’d been sourcing it from a supplier in Western Australia and one day I thought I’d like to meet the people who made it. So I went to northern Thailand to visit village communities and the textile markets at Chiang Mai where weavers from the Hmong villages in the area bring their work to sell. The Hmong have a distinctive palette in their fabrics which is quite different to that of other ethnic groups I visited, like the Akha. The colours vary in a way that I like, but I was also attracted by the evidence of the personality of the weaver. All the cloth is made on backstrap looms, which is why it’s always made to the width of their shoulders, but some of it is quite coarse and some of it quite tightly woven. I liked the idea of the direct relationship with the weaver that using this material gave me.

Six pieces in the exhibition described

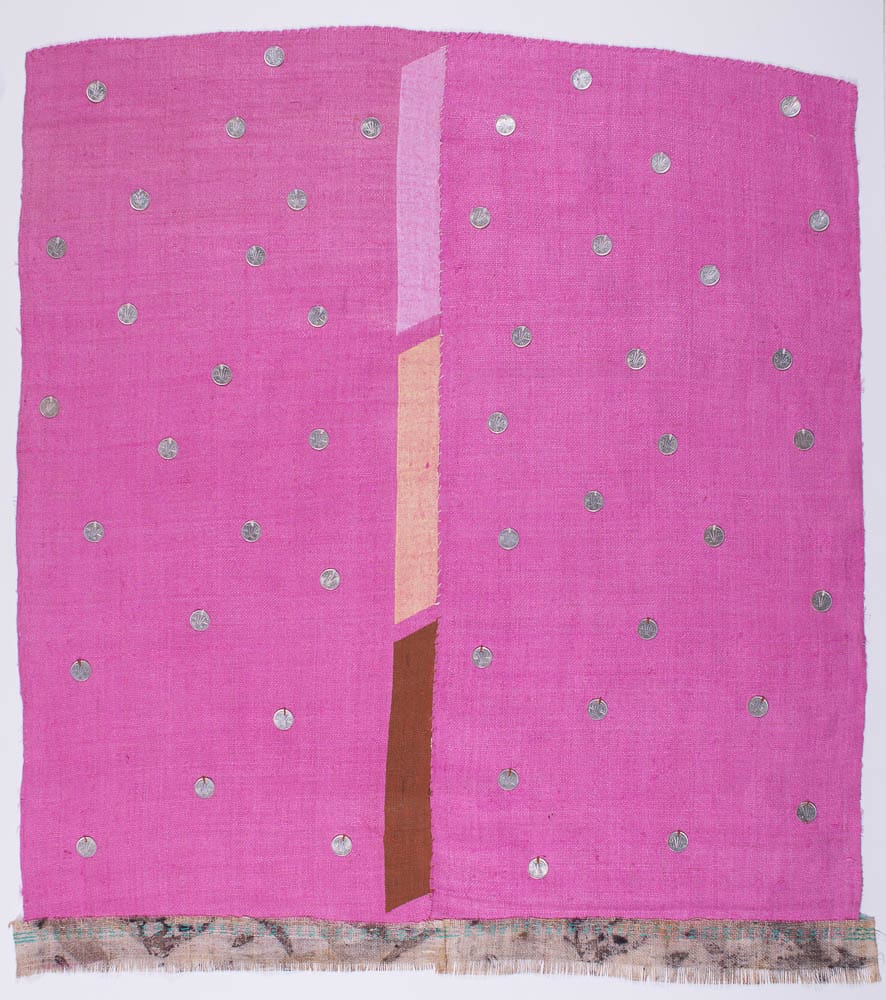

ANNE

Anne was my beloved spinster aunt who always made wonderful birthday cakes for her nieces and nephews. She was the reason I had a 21st. I didn’t want to, but Anne and her companion Alice had already bought the material to make their dresses with, so I had to go along with it. She inherited a big old rambling house in North Sydney full of old furniture. She was stuck with all this family stuff, which is why she liked new things of her own. I’ve tried to make something new for her in her favourite colours, pink and turquoise. It’s also made in layers like her birthday cakes used to be although without the threepenny surprises.

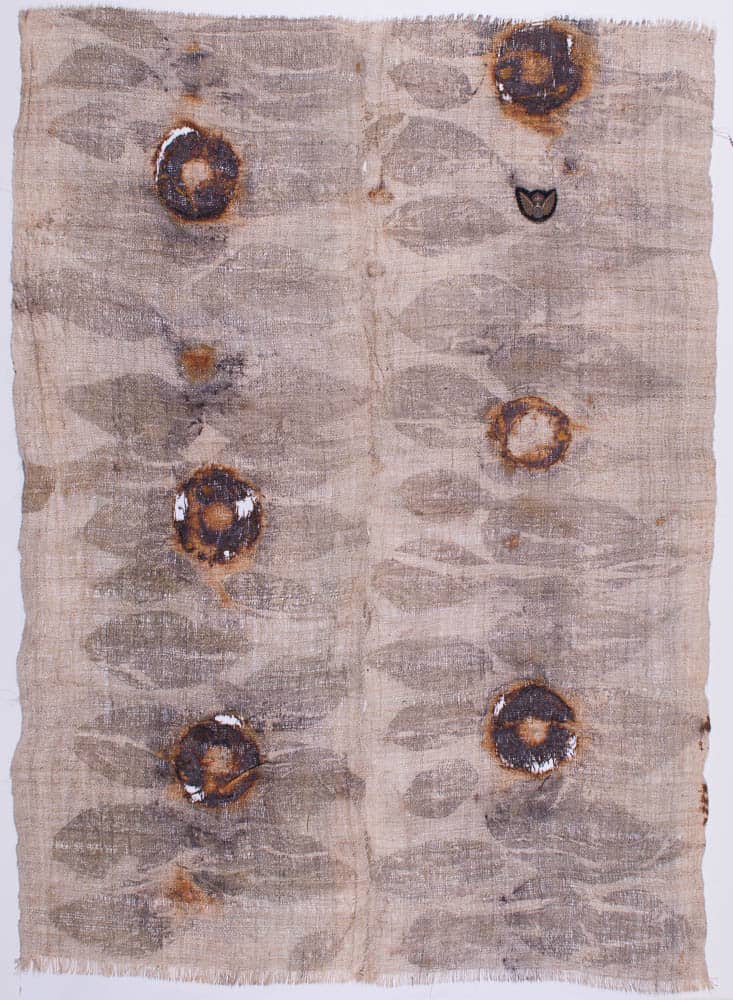

SHEENAGH AND DENNIS

Sheenagh and Dennis were my parents in law when I was married to Jeremy Cook. Dennis was a very English chap who served in the Fleet Air Arm during the war and Sheenagh came from a bohemian family in Sydney. Her dad was a well-known cartoonist and she had been a journalist herself before marrying Dennis. They loved nature and bushwalking, so I’ve used both natural and man-made things to make this piece. The corroded iron rings evoke portholes in sunken ships and something of the effect being a Navy wife had on Sheenagh.

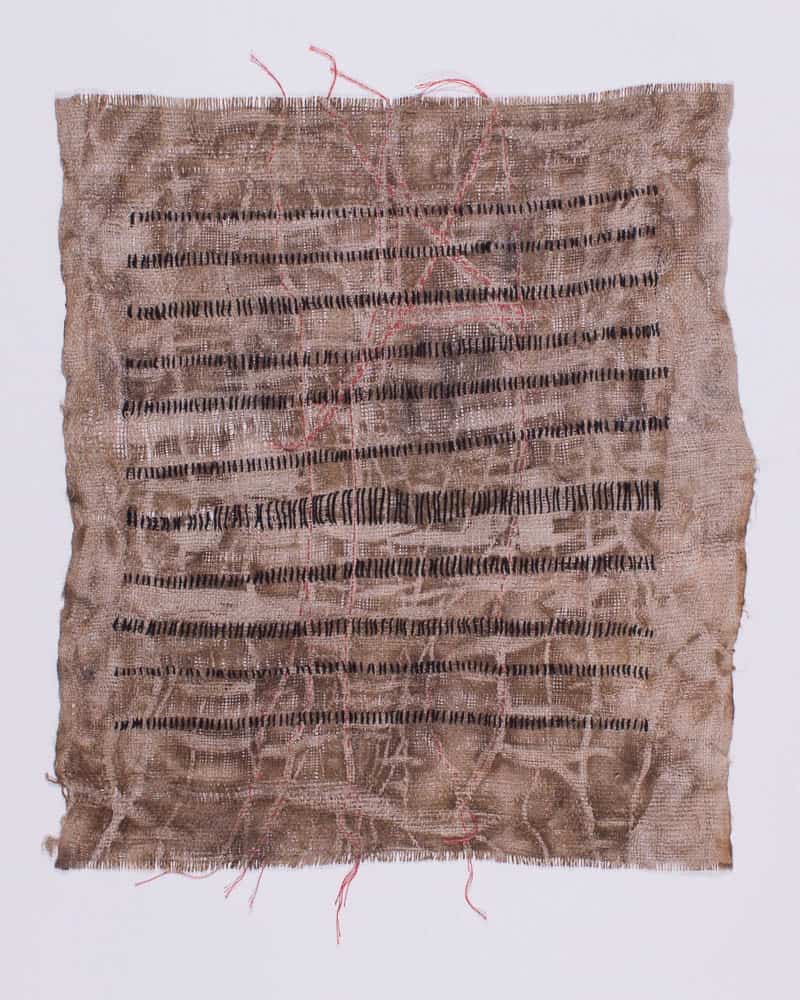

ADELE

Adele Horin was a well-known Sydney journalist who used to write for the National Times in its heyday. She was a friend I had in common with Frances McDonald who’s the subject of another piece in the exhibition. Adele was uncompromising, but she really loved company. Her piece is heavily stitched with rows and columns of black lines, rather like type on a page. The lines also refer to the way her writing made sense of chaos, and the unravelling and unpicking in the piece is a tribute to her work as an investigative journalist of social and political subjects. Adele was also a source for the exhibition as a whole because of her interest in end of life issues and the blog that she kept till the end.

MOLLIE

Mollie Bott was an honorary auntie of mine and one of the people who’ve been teachers to me. She was full of life and adored by her family and friends. Our relationship was much better than the one I had with my own grandmother. She loved doing crosswords and being the centre of things, which is why her piece is based a 3 x 3 grid with her in the middle. The mauve and purple were her favourite colours and when the fabric came out of the dye pot I immediately thought of her.

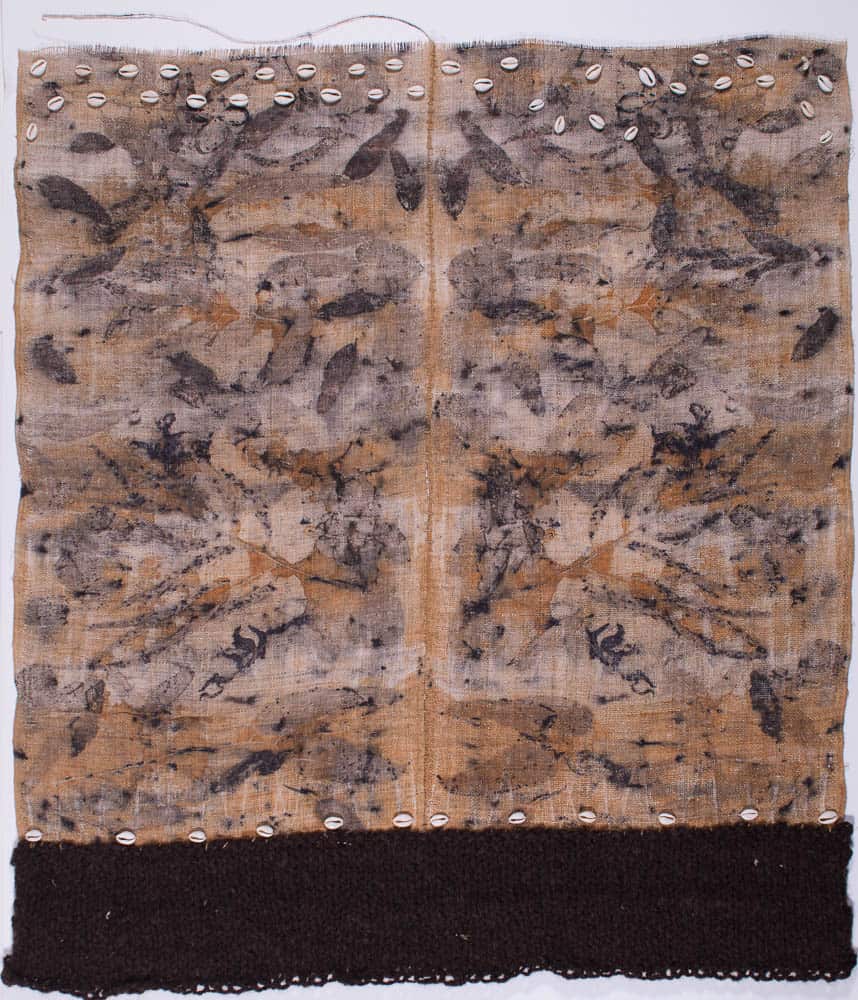

JOHNNO

Johnno was an early love of mine who got me interested in spinning your own textiles. We’d go for camping trips around Tasmania and the Northern Territory and always look for shells, cowrie shells in particular, which I reference in this piece. The colours are based on dyes made from eucalypts and grevilleas.

ABSENT FRIENDS

This is the first piece I made. It’s based on an idea rather than a person. It turned out so well I decided to follow it up. I was dyeing some material in which I’d wrapped natural elements like leaves from my own garden that made a kind of direct print that I liked. When I unwrapped the fabric after dyeing it spoke to me. Dyeing, printing, stitching and embellishing the fabric all came from this first experiment. They are very much contemplative pieces, each stitch making me think of the relationship I had with that person. Not a day goes by that I don’t think of one of my absent friends.

Author

Mark Stiles is currently a writer living in Sydney. Previously he had a short career in architecture and then a longer one in filmmaking, as a writer/director of documentaries. Recently he’s been teaching at various Sydney design schools. His interests lie in the history of Australian architecture and design. To this end he’s co-written a chapter in the anthology Sydney’s Martin Place (Allen & Unwin 2016) and is researching a proposed biography of the nineteenth-century colonial architect James Barnet. He also curated several group shows, including: 2011 Meditation Suite (Gallery East, Clovelly), 2013 Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin Centenary Tribute (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2015 Japan: Australian Perspectives (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2016 An Unbounded World (Gallery East, Clovelly)

Mark Stiles is currently a writer living in Sydney. Previously he had a short career in architecture and then a longer one in filmmaking, as a writer/director of documentaries. Recently he’s been teaching at various Sydney design schools. His interests lie in the history of Australian architecture and design. To this end he’s co-written a chapter in the anthology Sydney’s Martin Place (Allen & Unwin 2016) and is researching a proposed biography of the nineteenth-century colonial architect James Barnet. He also curated several group shows, including: 2011 Meditation Suite (Gallery East, Clovelly), 2013 Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin Centenary Tribute (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2015 Japan: Australian Perspectives (Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby), 2016 An Unbounded World (Gallery East, Clovelly)

Comments

I loved going through this interview. It has tremendous resonance with work that I’m engaged with, on a project called ‘Personal Threads’, where I collate the stories behind the artists work, inviting artists to write and share these.

In our contemporary world which stresses individuality, we have a plethora of stories – many untold and this diminishes our understanding of the unversality of the human condition. There is always a sense of feeling that in some way, our experience diminishes us because we don’t know what others feel in similar circumstances or that they even have encountered them. Therefore there is a growing insecurity, a lack in our capacities to love and forgive ourselves, therefore is less compassion, less patience and greater frustration. Owning our stories is a means to accept the experience, acknowledge the feelings and through the sharing, grow/transcend/change.

And, especially with textile practitioners, I think it could provide a crucial gateway towards a new patterning of textiles- an authentic expression of the millennial world. It’s not that I don’t cherish the old, I do, but our personal histories could augment this lexicon in ways that they can be carried forth, as have the traditional designs, which our individual offerings as art cannot. And most of what is being produced in the name of design is a cut-paste-regurgitation of the past, which doesn’t record the richness of lives lived in this fascinating age.