- Tsuda Nobuko, scholar of Ainu heritage cloth, is the first female Ainu PhD recipient in history. Here Tsuda points out an anomaly in the stitching of this kimono. This entire back pattern of the pattern is called the “sermak” and serves to protect the body of the wearer (Tenri Sankokan Museum collection)

- Tsuda and Nakatani Tetsuji, Tenri Sankokan Museum Curator, focusing carefully on the robe; Tsuda pointing out the enlarged tsuno tokki and explaining her thesis about what these might mean – apotropaic qualities of the cloth itself…

- anne-elise lewallen and Tsuda Nobuko

- Tsuda pulling a stray piece of thread from the kimono and analyzing to determine the type of fiber. In this case, irakusa thread (nettle), based on the texture, pliancy, and characteristics of the fiber… Same robe. Tsuda working to analyze the fiber itself: (Tenri Sankokan Museum collection)

- Use of very large tsuno-tokki on this robe indicate a strong prayer to protect and even ward off the potential of attack by payoka kamuy (deity of smallpox) and by Wajin men, who were known for sexually colonizing Ainu women, i.e. sexual assault and then taking them as “genchi tsuma” or as Ezo wives (Tenri Sankokan Museum collection)

- Reproduction of an Ainu attus (woven elmbast fibre robe) from the Hokkaido University Museum collection, produced for the “Handprints of Our Ancestors exhibit” (2009). Replica woven and embroidered by artist Uetake Yasuko (quoted in the chapter excerpt).

- Reproduction of an Ainu ruunpe (cotton appliqued robe) from the Hokkaido University Museum collection, produced for the “Handprints of Our Ancestors exhibit” (2009). Replica woven and embroidered by artist Yamamoto Miiko (quoted in the chapter excerpt).

The book The Fabric of Indigeneity: Ainu Identity, Gender, and Settler Colonialism in Japan contains important description and analysis of textile crafts practised by the indigenous people of Japan. We present a selection from the chapter “Embodied Knowledge (The Fabric of Indigeneity)” which focuses on the cultural context of Ainu textiles.

The most enduring aspect of Ainu cloth is the way that it knits individual Ainu to one another through prayer and as a vessel of the artist’s affection. This prayer animates the cloth and conveys a spiritual force to the wearer or owner, as Hasegawa Osamu explains (all personal names are listed in the Ainu and Japanese order; surnames precede first names).

I believe that these ancestral robes are in fact kamuy . . . and we humans have an obligation to protect and honor them. Whenever I leave my house, whether I wear it or not, I always bring my kimono along as a traveling companion. My robe is my tsukigami (J: guardian spirit). It’s critical to keep good relations with the spiritual beings around us. For me this means traveling with my guardian spirit every time I leave home. (Hasegawa 2005)

Ainu women insert their feelings toward their intended recipients into the cloth itself, “Stitch by stitch as the embroidery is sewn, the heart of the seamstress is inserted into the cloth of the garment. When the wearer puts the garment on his or her body, the sentiments of the artisan are said to be transmuted, and the wearer is protected by this passion, woven into the cloth itself, through the protective motif embroidered on the coat” (Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture 2007, 5).

Through this gift, producer and recipient become linked through the sentiment concentrated in the garment with each stitch of the needle. Even though settler colonialism has had a devastating impact on Ainu cloth-making, cloth artists across Hokkaido continue to imbue cloth with spiritual force by inserting a prayer during production.

In Ainu society, cloth serves as a vehicle for social relations. Fibers are processed and woven, sewn and appliquéd, making them Ainu as they are fused into cloth. In this process, they accrue political and symbolic valences, which are further amplified through revival. Historically, cloth both sustained and helped constitute personhood in Ainu society. The healing and protective properties contained in cloth were imparted to the wearer or bearer. Newborn infants were swaddled in worn, tattered attus strips or pieces of cotton cloth. These aged pieces bestowed the durability of old age to newborns and guarded against infant mortality, but they also commuted the personhood of the ancestors into the bodies of young babies and thereby tied the infants in to ancestral lineages. Cloth was also fashioned into medicine. Sakhalin Ainu shamans sewed cloth strips together in crosshatch fashion, infused these assemblages with spiritual properties, and fastened them to limbs, heads, and other ailing body parts as healing aids (Ogihara 2005).

Knowledge Rooted in the Body

Ainu knowledge is embodied knowledge. According to Ainu value systems, ethnicity and knowledge are rooted in one’s flesh, bones, blood, and heart. Rote memorization and recitation will not help a person weave bast fiber or carve a libation wand for a ceremony. Knowledge of how to fashion amip (A: Ainu clothing; bastfiber and cotton robes), as well as skill at embroidery, weaving attus, twining saranip (A: basketry), weaving citarpe (A: mats woven from rush) and emusat are all skills contained in the hands and hearts of Ainu women and are now being passed down (Enonkay, interview, December 2005). As one revivalist explained, “That elder who taught me so much used to chide me, ‘Remember with your body—not with your head!’ In learning from her, I came to understand the beauty of Ainupuri and Ainu life. Over time, I began to feel confidence as an Ainu myself” (Topeni, interview, July 12, 2001).

Historically, Ainu women created motifs to protect their loved ones and their own bodies, and they ornamented these clothes they made not simply for aesthetic enjoyment, but to guard family members against potential harm.

What I learned was that, in general, these things themselves embody expressions of the cultural milieu of the era in which they were created. And what I was learning from the elders was not just the techniques of making these things, but instead I learned an Ainu way of thinking, and a spiritual philosophy, and a posture of the heart…These elders taught me not only the production techniques, but also the world that they made through making these things, and they helped me grasp the spiritual world of Ainu. (Tsuda 2000, 93)

As mentioned above, Ainu motifs imbued with apotropaic qualities conveyed an added security to the wearer and embedded layers of protection. Motifs such as kiraw are believed to have been stitched in fabric as decoys to deter malevolent kamuy from entering the motif and possessing the wearer. Later this logic was transposed into even longer thorned extensions, stitched as a resistance code to protect women’s bodies from Wajin men’s intrusions (Tsuda 2014b).

Self-craft through Replica-Making

Crafting reproductions or replicas of ancestral cloth is an act of Ainu self-craft, as artists seek to acquire and reembody this ancestral knowledge by incorporating it as somatic memory. Revivalists argue that such meticulous reproduction, or proper form, links them to ancestral values.

My mother taught me how a woman should live, as well as how a mother should live. That was it—I had to make a replica for my mother! . . . Realizing I would never make a replica of the original with the fabrics I had bought, this time I started with plant dyeing. . . . If my work has anything in common with the original, it would be that I created it wishing for the health and safety (and the warding off of evil spirits) of my loved ones and that I simply wanted my mother to be overjoyed. (Yamamoto Miiko, quoted in Yamasaki, Katō, and Amano 2009, 72)

Engaging these unseen elements—the spiritual, cultural, and sentimental dispositions of the ancestors—has become a major motivation among artists. Revivalists insist this spirit of Ainuness hinges upon access to Ainu forms, in particular traditional patterns and techniques. First, a clothwork artist must master the processes behind these forms by literally making them anew, cultivating an ancestral somatic memory by embodying the comportment of the ancestors while making cloth. Artists contend that heritage forms (textiles, embroidery and appliqué designs and techniques, and the types of garments) must be faithfully conveyed to transmit the spirit and intention of the original artist. These forms themselves represent a sacred text that must first be committed to somatic memory before a clothworker can aim for unfettered self-expression.

When I first saw this garment, it touched my heart because I was so pleased to have the chance to make a replica of such a wonderful work by our ancestors. . . . . When I make a replica, I consider what the producer of the original might have been feeling while creating it, and I try not to compromise that sentiment. That is, I try to avoid doing it my way or choosing the easy way. Above all, the important thing is remembering to appreciate the works of our ancestors. (Uetake Yasuko, quoted in Yamasaki, Katō, and Amano 2012, 50)

Today a sense of nostalgia and a fascination with the ingenuity of ancestors in creating these masterpieces colors revivalists’ sentiments. Ancestors produced the heritage materials today considered works of art with limited tools and materials, often crafting them by the flickering light emitted from a solitary shell oil lamp. Moreover, ancestral artists imbued these works with spiritual conviction in the agency of embroidered motifs to repel evil. The idea of imparting ramat (A, soul/spirit) into one’s robe may not resonate with all Ainu women today, but the idea of cloth weighted with affection and prayer does.

This is an edited selection from Chapter 5: Embodied Knowledge (The Fabric of Indigeneity, pages 155-177)

References

Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture 2007. Message from the Ainu 2007: From Now to the Future. Sapporo: Nakanishi Insatsu.

Hasegawa, Osamu. 2005. “Indigenous Movements of the Tokyo Ainu.” Presented at Indigenous Movements in Plural Societies: The Canadian Inuit and the Ainu of Japan, international symposium at the National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, Japan, January 13–15, 2005.

Tsuda Nobuko. 2000. “Ainu bunka no fukugen to denshō wo mezashite—Seikatsu yōhin o fukugen suru denshō no jissen o tōshite.” In Hokkaido no seikatsu bunka, 78–103. Sapporo: Kita no Seikatsu Bunka Kikaku Henshū Kaigi.

Yamasaki Kōji, Katō Masaru, and Amano Tetsuya, eds. 2009. Teetasinrit Tekrukoci: Sennin no teato, hokudai shozō Ainu shiryō = Uketsugu waza. Sapporo: Hokkaido University Museum.

Author

ann-elise lewallen is Associate Professor of East Asian Languages & Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Since 2000, lewallen has lived and worked with Japan’s Indigenous Ainu community as an engaged scholar and advocate. Her research draws from critical indigenous studies, art and activism, gender studies, and environmental justice in exploring indigenous peoples’ struggle for self-determination and resource justice in Japan and more recently in India. Her second major book, In Pursuit of Energy Justice: Embodied Solidarity in India and Japan, investigates how discourses of science and politics shape development policy and impact indigenous sovereignty in transnational relationships between India and Japan. In her free time, lewallen can be found trekking the mountains of Indigenous Chumash country in southern California, collecting acorns and learning about Chumash cultural plants. She is author of The Fabric of Indigeneity: Ainu Identity, Gender, and Settler Colonialism in Japan (U-New Mexico Press and School for Advanced Research Press, 2016) and co-editor of Beyond Ainu Studies: Changing Academic and Public Perspectives (U-Hawai’i Press, 2014).

ann-elise lewallen is Associate Professor of East Asian Languages & Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Since 2000, lewallen has lived and worked with Japan’s Indigenous Ainu community as an engaged scholar and advocate. Her research draws from critical indigenous studies, art and activism, gender studies, and environmental justice in exploring indigenous peoples’ struggle for self-determination and resource justice in Japan and more recently in India. Her second major book, In Pursuit of Energy Justice: Embodied Solidarity in India and Japan, investigates how discourses of science and politics shape development policy and impact indigenous sovereignty in transnational relationships between India and Japan. In her free time, lewallen can be found trekking the mountains of Indigenous Chumash country in southern California, collecting acorns and learning about Chumash cultural plants. She is author of The Fabric of Indigeneity: Ainu Identity, Gender, and Settler Colonialism in Japan (U-New Mexico Press and School for Advanced Research Press, 2016) and co-editor of Beyond Ainu Studies: Changing Academic and Public Perspectives (U-Hawai’i Press, 2014).

Kaizawa Tamami

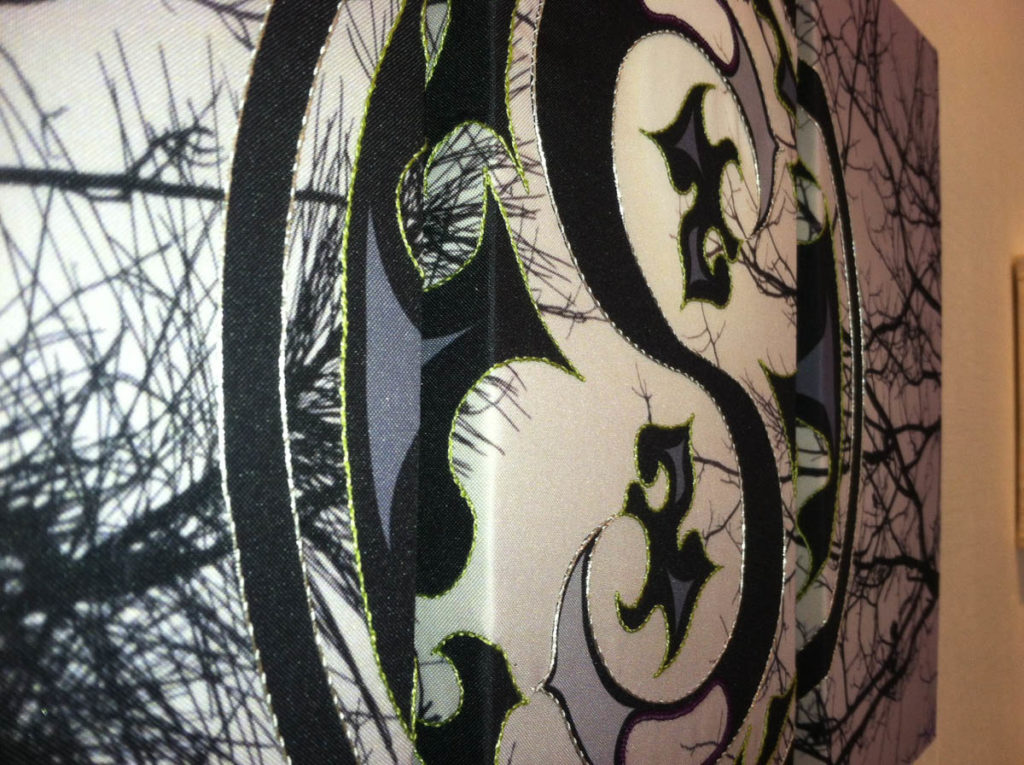

- Kaizawa Tamami , Four panel mixed media composition featuring Ainu heritage embroidery, reverse applique, embroidered into photographic image of Hokkaido sky printed on silk. Materials: Silk and cotton embroidery floss, cotton and silk cloth (Photo courtesy of the artist).

- Kaizawa Tamami, Triptych series. Heritage embroidery pattern rendered on enlarged dewdrops. Embroidery rendered on photographic image of wild garlic leaf (A, kitopiro) sprinkled with dewdrops. Materials: Silk and cotton embroidery floss, silk-imprinted with photograph. (Photo courtesy of the artist)

- Tryptych montage of Ainu artist Kaizawa Tamami’s three-dimensional embroidery. This piece is now a part of the permanent collection of the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, Japan. Materials: Silk and cotton embroidery floss, silk applique, silk-imprinted with photograph. (Photo by author.)

The book by anne-elise is a fantastic opportunity to spread understanding and interest in Ainu culture. In the past, father and grandparents faced painful discrimination because of their race. I remember as a little girl that parents of my schoolmates did not let me visit their home. It’s similar to other invaded peoples around the world.

Ainu strive to live hand in hand with nature. We walk with nature, as our ancestors have done, in a spirit of respect for the natural world. This is not unique to Ainu; as humans, all of us need to care deeply in this way. Ainu patterns express a deep sense of gratitude for nature. We have to eat to live. We not only take the lives of animals, but we also recognise that wild mountain vegetables that we collect for food are living beings. The bear, salmon and deer are ranked high in our spirit system.

The festival for welcoming the salmon, asir cep nomi, today involves a kamuynomi prayer for the new first salmon. We also perform a small ritual before we enter the forest in which leave a small offering and ask permission from the forest spirit-beings, promising to be modest in our needs and seek protection.

While our culture is no longer on the brink of erasure as it was a century ago, we are still striving to revive our traditions. My main focus is to recover Ainu designs and patterns. I draw particularly on the designs from my home village of Nibutani and Bitatori, using embroidery and applique techniques.

Our word for greeting is irankarapte, which means literally “let me touch your heart softly”. But I especially like the expression for gratitude, iyayraykere.

This statement was taken from a Skype conversation translated by ann-elise lewellan on 2 December 2018

Author

Kaizawa Tamami is a contemporary artist and Ainu designer who has recently been commissioned to produce public art for the new Ainu gallery in the tunnel under Sapporo station in Hokkaido. Her art contribution will feature Hokkaido’s four seasons rendered in three-dimensional Ainu forms. In addition to textiles, Tamami’s designs feature a broad range of products including lamps, wall hangings, clothes, graphic design and packaging materials.

Kaizawa Tamami is a contemporary artist and Ainu designer who has recently been commissioned to produce public art for the new Ainu gallery in the tunnel under Sapporo station in Hokkaido. Her art contribution will feature Hokkaido’s four seasons rendered in three-dimensional Ainu forms. In addition to textiles, Tamami’s designs feature a broad range of products including lamps, wall hangings, clothes, graphic design and packaging materials.