- Emblematic of Kastellorizo, the Boukla is a domed shield-like gold- or silver-plated fibula. A series of six were used to close the front of the white shift worn by women under long silk or velvet coats.

- Hamaili are small protective amulets that were to be hung on children’s cribs. This triangular piece is decorated with copies in gold of Venetian ducats. Maker unknown. Date unknown

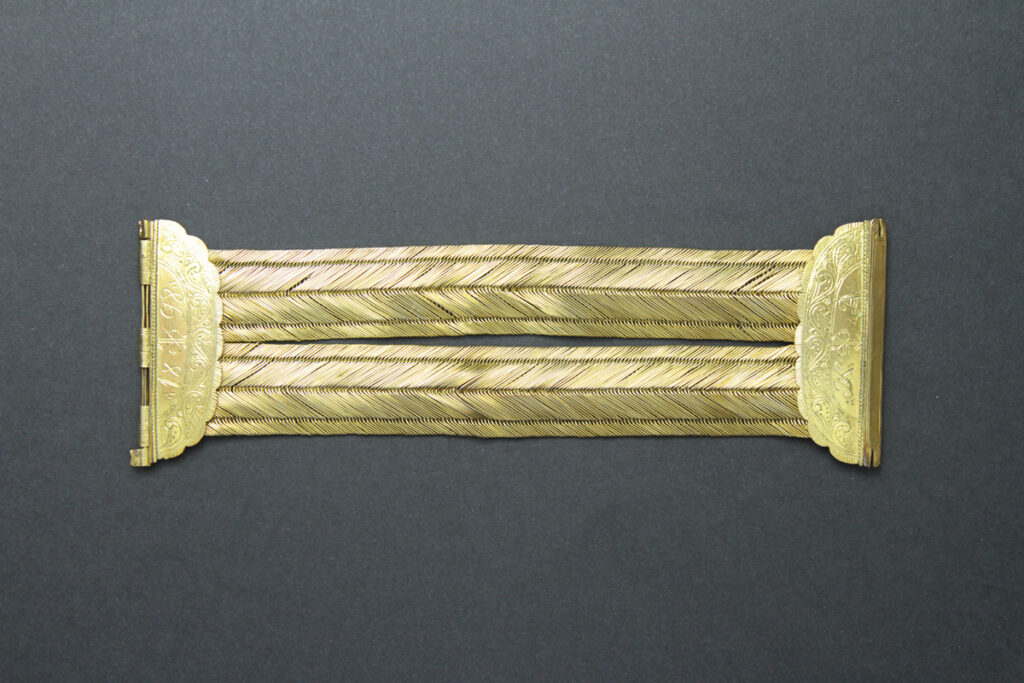

- A cuff bracelet fashioned in Tserkino, and with a shield like clasp. Tserkino is a particular herringbone design of plaited gold wire with the appearance of woven straps. Maker unknown. Dated 1898.

- An example of the richly coloured and gold embellished fabrics worn with by women along with the jewellery. This is a segment of a kavadi, a traditional Greek long outer garment. The Kastellorizian version

- This Stravoflouri is typical of the almond shaped, high quality gold pendants given to newborns, often by a godparent. Embellished with scenes of annunciation, birth and rebirth, they might also include

Kathryn N. Couttoupes reviews a book about jewellery from a small island whose craft heritage exceeds its size.

Nicholas C. Bogiatzis, Kastellorizian Jewellery: A Dispersed Archive of a Past Culture Published by Halstead Press, Australia, 2020

Kastellorizo is a very small island in the eastern Mediterranean, the easternmost populated land of modern Greece, just two kilometres from the south-west Anatolian coast of Turkey. Its merchants (and pirates) were active in the ancient world as well as during the middle ages and into the twentieth century. It was “for centuries… a Greek population within an Ottoman world”. Then, in the 35 years to 1948, it was under Ottoman, independent, French, Italian, British and finally Greek rule. Its peak of prosperity in the second half of the nineteenth century had much to do with both its geopolitical position equidistant from Smyrni, Beirut, Alexandria and Athens, and because of its deep harbour providing easy access to Ottoman ports, the Silk Roads, the Black Sea, and the Suez Canal. Its position within the Ottoman Empire and its consequent ability to exploit the resources of the Anatolian coast were key factors in its prosperity and demise. The disintegration of the Empire and the emergence of the Republic of Turkey ended this profitable relationship. From 1910 to 1946 the population shrank from 9,000 to 200. Tourism, especially by Australians of Kastellorizian-origin, has been the major source of income over the past thirty years. Today it is at the centre of contests about marine rights and fuel resources under the surrounding waters.

The Kastellorizian diaspora has spread to many parts of the globe since emigration began in earnest from the very late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the island was increasingly caught between the nationalist and colonialist aspirations of east and west. They went in search of new opportunities and to do business in more promising lands. Some emigres were lucky enough to be able to hang on to and take with them their treasured jewellery. And it is for this diaspora and for the jewellery itself that Nicholas Bogiatzis has written this slim and sumptuous volume. Intended as an accessible archive of the jewellery forms—their cultural and emotional meanings and their economic purposes—it is presented in an accessible style and richly beautiful, thoughtful format. He aims to preserve and share the results of his research, especially for the “custodians” of this cultural heritage.

The author, himself an Australian of Kastellorizian descent, is not a specialist maker of jewellery nor a dealer but a well informed and keen collector of pieces that were once worn in Kastellorizo. Some were made there and on the Anatolian coast. Many have been acquired throughout the trade routes described above. He is passionately committed to sharing his knowledge with the inheritors of these artefacts, most of whom no longer live on the island. They are third, fourth, fifth and sixth generation diasporans, stretching from Brazil, the Horn of Africa and Mozambique, modern Greece, Russia, the US and Australia.

The book’s cover in rich dark browns and gold makes a promise that is well kept. It’s a good read. We are led into the story through a series of double-fold illustrations of individual jewellery pieces. The settings at each of these introductory openings alternate between dark and light, contexts which reveal the deep glow and glittery bling of the pieces. They hint at the cycles of prosperity, destitution and tragedy that is the island’s history, a history reflected in the extract from a George Seferis poem that is included at the front of the book.

The text is informative and illustrated with well-selected, beautifully reproduced photographs of the jewellery and of the clothing and fabrics it was intended to be worn with. This is part of the message of the book. The clothes and the jewellery are made for each other. The rich colours of the fabrics, embroidered in gold thread, contrast and background the sparkle of gold, silver and precious stones. He explains how these pieces constituted much of the stored wealth of the society and were worn, mostly but not always, by the women as an indication of family position in what was a highly socially stratified population. Thus they indicated availability of the wealth for mercantile and marriage contracts.

In describing the categories of jewellery—necklaces of gold coins, brooches, rings, crosses, boukles (a type of clasp), earrings, bracelets, chains, children’s teething devices and baptism whistles—he explains their functions: practical, social, economic, spiritual, superstitious. These functional aspects of the jewellery are more important than their role as fine art. It the significance of these aspects that he hopes to communicate to those inheriting what at first might seem random pieces of nostalgia. He gifts the recipients of this heritage the opportunity to share what he has learned and understood about the cultural meanings of the artefacts and hopes to encourage them to keep, wear, treasure and preserve them. He also hopes, perhaps, that they will find, identify and reinstate long lost or forgotten family artefacts that are in fact treasures.

He outlines why the jewellery forms are often repeated in size, shape and design and are not necessarily finely wrought, individually designed pieces. The designs and making—in the past and today—reflect both the conservative aspects of the culture as well as its openness to change. This jewellery is still being worn, some still made, remade, refashioned, repurposed and is an inspiration for new pieces based on old forms.

In a brief history of Kastellorizo, he establishes that the jewellery was made possible through the prosperity of the island’s trade and commercial ventures. He includes a brief and selective ethnography of the owners and wearers of the artefacts—the wealthy ship owners and merchant families. The writer explains how and to what purposes and effects—in addition to adornment—the specific types of jewellery were worn and used. They not only signify status but include talismans and crosses deeply imbued with wishes for blessings and the absence of evil in a very religious and superstitious society; exchanges of wealth within the marriage contract; thread holders in the making of fabrics; and children’s toys.

The section about the making of the jewellery is interesting but brief. Some of this was difficult to research, given that much was imported from far and wide and that marking of precious metals was not consistent in the Ottoman world. He reports on the use of filigree and granulation, wirework and casting, cannetille and real and “counterfeit” coinage.

Coins are extensively used in the jewellery, as they are across much of the east. They evidence the island’s long history within the Roman, Eastern Roman (Byzantine) and Ottoman Empires. They also document (in gold) the inhabitants’ travels and trade across Europe, the Mediterranean and the east. A chapter is devoted to coinage and the book includes a fascinating appendix about one special coin, the konstandinata, whose forms can be traced from Venice to Egypt and to Kerala in south India.

There is also a glossary of Kastellorizian jewellery terms. Some of this information is already covered in the previous chapters, but collected here in this alphabetically listed summary it makes for an easy review of the jewellery forms and the Greek and Kastellorizian dialect words, meanings and possible origins. As I read this section though, I wished that it included page numbers where I could refer back to an image of the item described.

Though obviously well researched, there is no bibliography, no footnotes or index. This fits with purpose: to tempt the current guardians of these artefacts to pick up and finish reading the book and thus connect with the meanings of the wearable objects; see what they meant to their ancestors and original makers and possessors, and understand more about the significance of their treasures. But obsessives like me do miss the possibility of further reading, checking out the “it is possible that”, “it is thought that” which crop up.

You can judge this book by its cover. It is indeed a beautiful and fascinating production. I look forward to any follow–up publications on newly found pieces of this jewellery; more on their making; and perhaps a volume on the fabulous “traditional” fabrics and garments worn by the women in times gone by.

Visualise the women in a multitude of richly coloured, luxurious fabrics sourced from the east and west, including furs. Add as much gold jewellery as possible. More importantly, add an attitude of confidence created by wealth and matrilineal property inheritance.

“The Kastellorizian Woman’s Costume”, Geoffrey Conaghan, Filia, Friends of Kastellorizo, Edition 43, Winter South/Summer North, 2019

The book can be purchased here kazzijewellery.wixsite.com/book