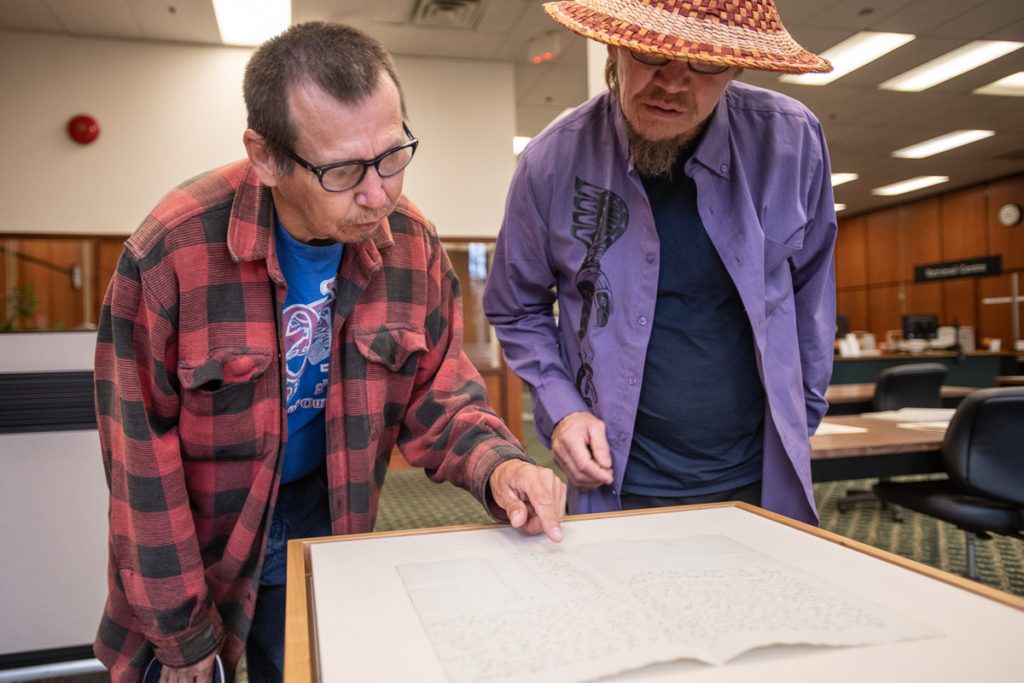

- Jacobson brothers viewing the treaty in the BC Archives reference room

- BC Archives

- BC Archives

- BC Archives

Rituals of thanksgiving have become an essential part of Genevieve Weber’s work as an archivist as she confronts its colonial legacy.

The BC Archives, part of the Royal BC Museum, is located on the territory of the Lekwungen people, known today as the Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations. As the official repository for the government of British Columbia, the collections contain myriad records depicting the Lekwungen, and other Indigenous peoples, during the early settler period. Hand-drawn maps portray traditional territories and use of the land, showing buildings, hunting and fishing grounds, and sacred burial sites; settler accounts describe local customs; and photographs illustrate public ceremonies being observed by the settler population. The job of the archivists is to process new acquisitions of records, describe them in order for researchers to understand our holdings, and to make them accessible in the reference room or online. As a settler working as an archivist in a colonial institution that controls, protects, and provides access to Indigenous expressions of knowledge, I am acutely aware of my position of power.

Traditional European archival practice is taught as a science: the archivist is removed from the material, expected to remain disengaged from its contents, and told to approach it in a clinical manner. Archivists are trained to be objective caretakers of the material, not to interpret or analyze contents. This approach results in the perpetuation of silenced populations and histories in the archives. In recent years there has been a shift in the archival community: the impossibility of neutrality, as well as the harm that attempting to remain dispassionate can cause, has been recognized by some archival theorists. Acknowledging this shift means that archivists must emphasize records that bring the previously silenced voices forward. Although still in a position of power, this shift makes the archivist more vulnerable and exposes them to records of trauma, abuse, neglect and pain.

The BC Archives holdings include government and non-government (private) records in all formats: textual, photographic, audio-visual, and cartographic. Although European notions of archival creatorship consider most of these records to be non-Indigenous—they are created by a government entity or private individual about Indigenous people —many of these records contain Indigenous traditional knowledge and histories. Indigenous concepts of ownership and creatorship are drastically different from Euro-Canadian views, meaning that the voices on a recording hold precedence over the sound disc on which a song is preserved, and the intrinsic knowledge of traditional hunting grounds is more significant than the linen trapline map on which a hunter’s trapping rights are recorded.

Over time, rituals and acknowledgements of thanksgiving have become an essential aspect of my work. When we as practitioners are grateful for the opportunity to work with sacred information, with traditional cultural knowledge, and with records documenting historical wrongs done to Indigenous peoples, we begin to loosen the power of the colonial record and thus begin the difficult task of decolonizing the archive. Gratitude allows me as an archivist the space to grieve the past and be thankful for the present; it allows me to recognize the equal—or greater—importance of Indigenous traditional knowledge in the archives, and it strengthens my role as an ally.

WHY gratitude

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s final report, published in 2015, included 94 Calls to Action. Calls 67–70 are directed specifically at Archives and cultural memory institutions, but there are many others that relate to the work that we do at the Royal BC Museum and Archives. Although other events in the past, such as the publication of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996, have led to discussions regarding Indigenous information and records in archival theory, no other policy has spurred the same level of change in Canadian archival practice as the TRC calls to action. 1.For examples see: Greg Bak, Tolly Bradford, Jessie Loyer, and Elizabeth Walker, “Four Views on Archival Decolonization Inspired by the TRC’s Calls to Action,” Fonds d’Archives 1 (2017); Steering Committee on Canada’s Archives: Response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Task Force, “Report on the Results from the Survey on Reconciliation Action & Awareness in Canadian Archives (2017),” Steering Committee on Canada’s Archives: Response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Task Force (May 2018); Genevieve Weber, “From Documents to People: Working Towards Indigenizing the BC Archives,” BC Studies no. 199 (Autumn 2018). Many archival professionals are looking to ways to rectify past injustices and to make Indigenous records more visible, accessible, and appropriately described. This work is essential. Some people are hesitant to start for fear of getting it wrong. As settlers grapple with both historical and contemporary Indigenous realities, fear often turns to guilt, or possibly to empathy which, however well-intentioned, is still colonial in nature. We are called by Indigenous colleagues to push these feelings aside and be bold, to listen, to welcome and learn.2.Jessie Loyer in Bak et. al. “Four Views on Archival Decolonization,” 17 Once we succeed in doing so, there are consequences of facing this monumental task. As archivists process, research, and provide access to records, they have no choice but to engage in the traumas described within. Archival professionals involved in document discovery projects for the TRC spent months, sometimes years, immersed in deeply traumatic records, a task that has had lasting negative effects on the people doing the work.3.For a personal reflection on the effects of working with records of trauma I recommend Melanie Delva’s account titled “Small, Cold Hands: The Dangers of Excising Self from Service” from her presentation made at the Association of Canadian Archivists annual conference, Montreal QC, 2016. The profession is only lately beginning to seriously discuss the ramifications of working with records of grief, pain, and trauma.4.An initial study looking into cases of secondary trauma has been published and further studies on Conceptualizing Recordkeeping as Grief Work is underway. For the study on secondary trauma, see: Katie Sloan, Jennifer Vanderfluit, and Jennifer Douglas, “Not ‘Just My Problem to Handle’: Emerging Themes on Secondary Trauma and Archivists,” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 6, Article 20 (2019).

In my own processes of decolonizing myself and doing my job well, I need to move away from the knee-jerk reactions of denial, guilt, shame, or even empathy. Gratitude and thanksgiving focus my reaction on the positive and allows me to move forward with my work in a way that is respectful and open without minimizing historical truths. Gratitude aids with coping strategies, increases humility and leads to better outcomes at work. Gratitude is often clustered with hope, which is crucial in this process. And so, I am boldly moving forward in my work with gratitude as my tool.

HOW gratitude

In order to guide my work with gratitude, I have to make the work people-centred. Processing records is not about words on paper, seals and signatures, photographs, sound recordings, and moving pictures. It is about the people whose lives are embedded in those records, and whose memories we honour when handling them. We are shifting the focus away from the notion of the archivist as a caretaker of the records towards that of a caregiver bound by relationship to the records creators, subjects, users, and communities. By adopting an archival practice based on radical empathy, we alter the power imbalance and honour people first.5.I rely heavily on the work of Marika Cifor and Michell Caswell in their paper “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives,” Archivaria 81 (Spring 2016): 23–43. For an examination of how we have applied these principles at the BC Archives, see Genevieve Weber, “From Documents to People: Working Towards Indigenizing the BC Archives,” BC Studies no. 199 (Autumn 2018

I recently began processing an acquisition that includes records relating to Residential schools. The records were, for the most part, created by the administrators and staff of the schools. The students that attended the schools are often the subject of the records. The survivors and their families will likely be a primary user group. The records connect with many communities: those in which the schools were situated; those from which the students were taken; survivor-led support groups; and more. As I began to bring the boxes onsite and conduct an initial review, my supervisor asked me what could be done to support me as I embarked on the demanding task of processing these potentially traumatic records. Together we agreed to bring in two women to cleanse and bless the space. Marilyn from Tseycum and Linda from Cowichan arrived at the archives with cedar boughs. After a brief inspection by the conservator for insects, we went into the stacks where I have been working. Approximately one-third of the collection was on site on shelves. Staff were invited to join us, and a group of about a dozen people squeezed into the narrow workspace. The women spoke to us about the heavy atmosphere they felt when they entered the stacks. They spoke to us about the importance of our work, and about self-care. But mostly, they talked about the people.

The cedar boughs swept the air around the boxes of records, a gentle breeze forming in the normally still space. Marilyn and Linda’s voices murmured as they worked to cleanse the room and shift the atmosphere. After brushing the workspace they turned to each staff member. As the boughs swept over heads, shoulders, arms, backs, and chests, the women spoke to us individually, commenting on the importance of our work and reminding us to be kind to ourselves during this process. The records, they told us, are not only paper, cassettes, photographs. They are people. They are not recorded memories of people: they embody the spirits of the children, the parents, staff of the schools. When we touch a letter, we are holding a person and must treat it accordingly. This knowledge has come to shape the way I approach the project: each time I open a box, I keep the people present in my mind. Sometimes the records are mundane, describing the administration of a school, listing financial transactions. I remind myself of the children that were affected by each number on a page. A budget report with columns showing how food was distributed is a reminder of each child that ate a meal at the school. A receipt for a replacement boiler bears the memory of a cold child shivering in a bed far from home. The children are ever-present, even when their names are not written on the page. Their faces stare back from photographs.

The BC Archives has been involved in a series of dialogue sessions led by the Residential School Centre for History and Dialogue at the University of British Columbia. The centre arranged the dialogue sessions around the province to meet with Indigenous people, specifically residential school survivors, and members of the research and information communities. The purpose of the sessions was to consult and gather feedback regarding the use and sharing of residential school information. In the sessions, we heard from survivors that understanding the truth of what happened to Indigenous people in Canada is essential as it leads to healing. Centering the work on the people in the records and bearing witness to the truth is the first step: the next is meeting with survivors and family members. This is when I most profoundly experience gratitude. No matter what the nature of one’s work is, opportunities for employees to be in contact with the people who benefit from that work are a key way to foster episodic gratitude in an employee. Whether this takes place in the reference room or in a community hall, meeting with residential school survivors, Indigenous researchers, Elders groups, and community members are by far the most rewarding aspect of the job. A connection is made when a researcher hears his father’s voice speaking to him across the years through a headset, or when a survivor sees a photograph of themselves at school: these moments are invaluable. Connecting the intangible memories, emotions and suffering with a tangible item from the past brings validation and relief. These are the moments that bring meaning to the archival process. It is not my belief that my predecessors in the archives were indifferent to the users, but in the process of professionalization the information community relegated their importance in favour of the records. For me, the connection with the people is the entire purpose. Without considering the records creator, the subjects, the users, and the community, there is no reason for the work. When that connection is made, the pieces fall into place, and I am extremely grateful to be given the chance to do this work.

CASE STUDY: The Vancouver Island Treaties

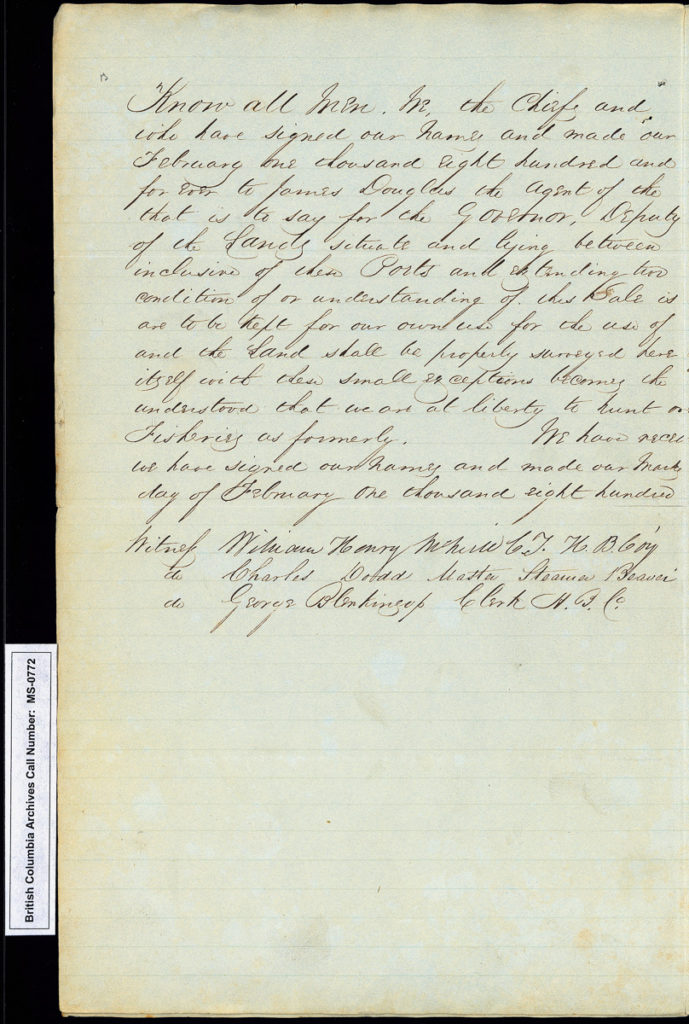

- Page one of Kwaguʼł treaty; photograph courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

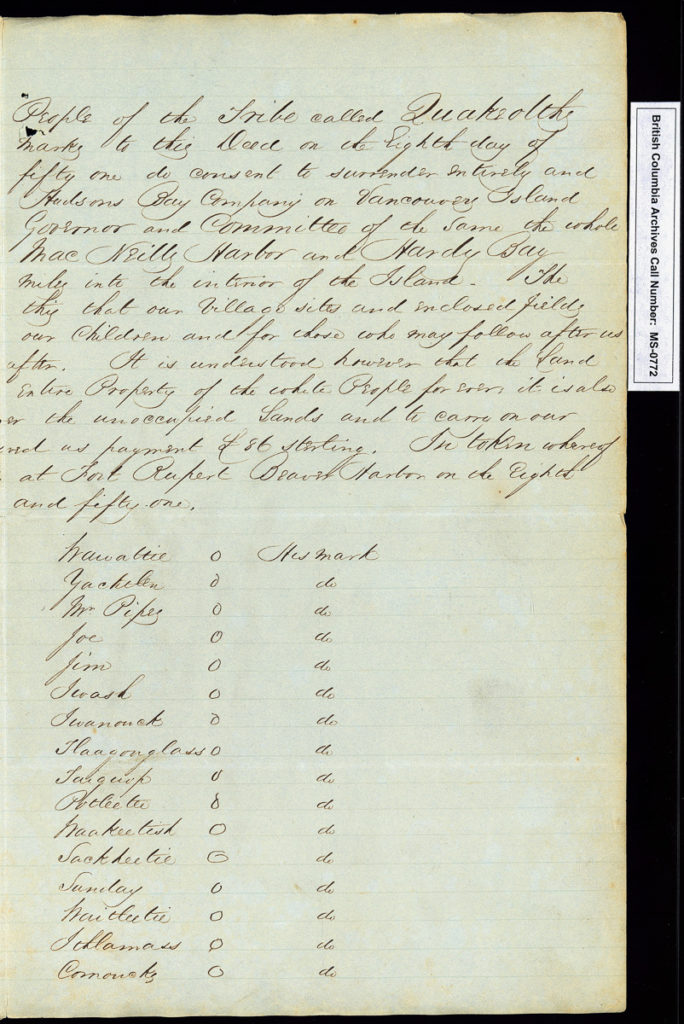

- Page two of Kwaguʼł treaty; photograph courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

It is early morning near the end of summer. I have come in before any of my colleagues to prepare for a visit that will take place in the reference room before it opens to the public. The Jacobson brothers, who have been participating in an Indigenous Artists program at the museum over the summer, have requested to see their community’s treaty. I am anxious: about having the extremely fragile and valuable treaties out; about correctly vocalizing the nuance around the treaty’s ability to simultaneously take away and protect Indigenous rights; about ensuring I don’t offend or make a cultural faux pas throughout the meeting.

The Douglas Treaties, often referred to these days as the Vancouver Island Treaties, are colonial-era agreements made between the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) on behalf of the British Colony of Vancouver Island. HBC Chief Factor James Douglas met with Indigenous leaders to arrange purchases of land for the company. However, these are more than simple financial transactions: copying wording used in similar agreements made in New Zealand, the terms of the treaties promise that the Indigenous communities will retain existing village lands and fields for their use, and also will be allowed to hunt and fish on the surrendered lands. The treaties are controversial as it is almost certain that the Indigenous leaders had a different understanding than Douglas of the terms of the agreement, yet they are critical in ongoing disputes over land rights.

Of the fourteen agreements, eleven are inscribed in a bound volume, and three are on loose sheets of paper. The Jacobson brothers have come to see one of the separate pages, the treaty relating to their Kwaguʼł community, part of the modern-day Kwakiutl First Nation. The page is carefully propped up at a readable angle on a podium and locked under a plexiglass case. The podium has been put in direct view of security cameras, and we have a security guard nearby. I am uncomfortable with the heavy-handedness of the setup, but it is a necessary compromise to allow access to the documents. Next to the podium is a high-resolution reproduction of the document. Except for the texture of the paper, the reproduction and the original are identical. Concise, attractive cursive in faded ink articulates the agreement that has shaped the reality of the Kwaguʼł. My hope is that the brothers’ disappointment with the distance they are forced to remain from the original is tempered by being allowed to handle, turn, and read up close the copy. I assume that tactile experience is what they are looking for, as I know they have seen the digitized copy online.

In the reference room, I am acutely aware of the imbalance in power. The document is about the Jacobson’s family and community, yet they can only look at it through glass. I, a privileged employee of the government and a person that has never been to Fort Rupert and the surrounding area, can touch and hold the treaty. They need to make an appointment and travel many hours to the archives to view the treaty, whereas I can see it every day if I choose. They are treated with respect but ultimately a level of suspicion reserved for all non-employees (hence the security), whereas I am given keys, passes, and alarm codes providing me free access.

When Dave and Jonathan arrive, to my surprise, they pay no attention to the security, they brush off my bumbling attempts to guide them to the reproduction, and they head straight for the podium. It is as if they are drawn to it. The glass doesn’t seem to matter as a hush falls over the room. The only sound for the first minute or two is a quiet mumbling as the brothers peer through the glass at the faded 160-year-old page. They recite the traditional names listed as signatories, still recognizable despite their anglicized spellings. I keep my distance, answering questions or responding to comments as appropriate, but giving them space to do what they need to do. Then Dave beckons me to stand next to him.

Can you feel it, he asks? – The breath of our ancestors. Those that came before us stood by this document and breathed the air around it. You are lucky. You touch these documents regularly, and when you do, you breathe the breath of our ancestors.

I feel it then.

Gratitude.

It is about people. The documents are our connection to people: the people that touched them, that read them, that composed them, and that are described in them. The people that come to be with them today. I am honoured and so very grateful to experience this moment, and to connect with all the people in room, visible and invisible.

CASE STUDY: Huu-ah-aht land purchase

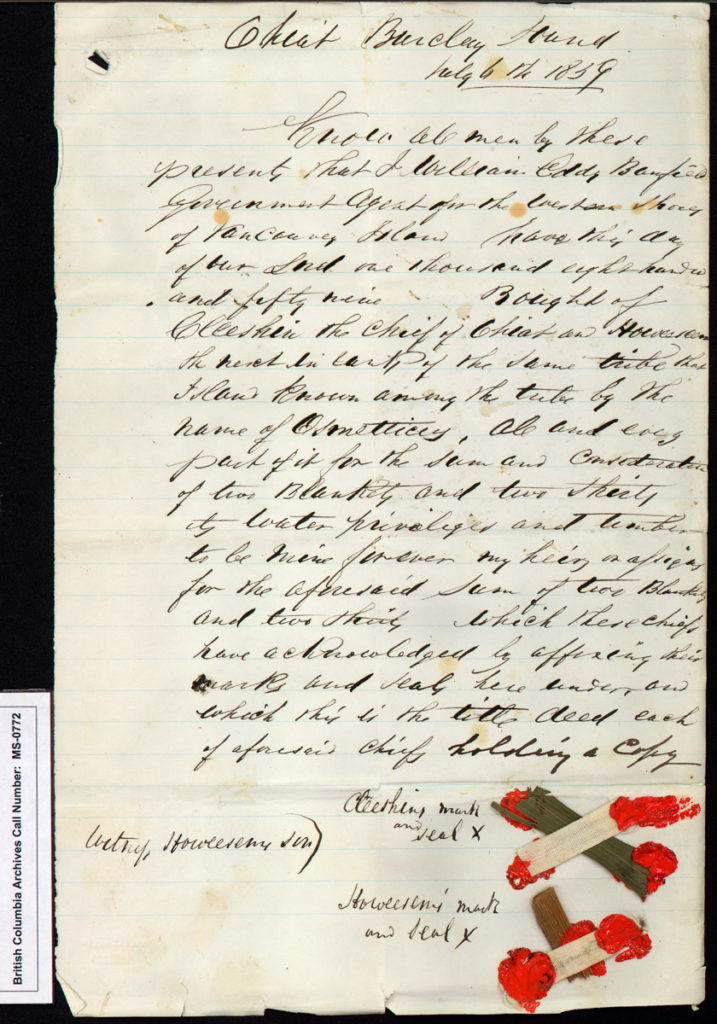

Banfield document with cedar bark/sailcloth signatures; photograph courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

Stored alongside the Vancouver Island Treaties is another paper documenting a land purchase. In 1859 William Eddy Banfield purchased Runce Island from the Huu-ay-aht, Nuu-chah-nulth people living on the west coast of Vancouver Island. This document is not a treaty as it does not enshrine any rights to land; it mirrors a European title deed. It is, without a doubt, a colonial document providing a glimpse into early transactions between the Indigenous population and non-Indigenous settlers, which had devastating consequences. It cannot be denied, however, that this document is starkly different to others from the same era. Firstly, it provides evidence that early settlers recognized Indigenous title to the land, and although they approached it with a paternalistic, colonial attitude, completely misunderstanding the complex local model of land stewardship (rather than private ownership), it does corroborate the Huu-ay-aht history of their traditional lands. But the most striking aspects are the signatures and seals.

James Douglas used a mix of Indigenous tradition and European to ratify the Vancouver Island treaties. The treaties were negotiated orally at the top of PKOLS (Mt Douglas in Saanich, BC). The signatories marked a blank page with an X (whether or not they actually made the mark is debated) and their names were added at a later date. Banfield, too, blended European and Indigenous traditions in formulating his land deed. The signatories to the Banfield land purchase are the Head Chief “Cleeshin” (likely Tl’iisin in modern spelling, a hereditary name) and the next in line, Howeesin. The agreement was likely made orally as well 6.Banfield to Colonial Secretary V.I., Ohiat, 4 March 1860, BC Archives: Colonial Correspondence GR-1372., but in the written version he included a special seal next to the names of the signatories. Next to the two names is an X made from a strip of cedar bark, crossed with a strip of sailcloth, sealed with wax.

The cedar-wax seals are a traditional symbol used by the Huu-ay-aht in negotiations. In 2016 when the terms of the Maa-nulth Treaty to return cultural treasures from the Royal BC Museum were met, the Huu-ay-aht Chiefs signed the agreement with the museum using a cedar-wax seal.7.There are many examples of agreements between the Huu-ay-aht Nation and companies, such as forestry companies, with the cedar-wax seals. To read more about the Royal BC Museum transfer of cultural treasures and to see video footage of the seal being added to the final documentation, go to the Royal BC Museum website.

I see the cedar seals as symbolic of the archives and our goals in regards to truth and reconciliation. The archives is a colonial, government agency: there is no denying this truth. Rather than whitewashing the past, we can strive to highlight the information of importance to Indigenous communities, and recognize Indigenous sovereignty over their information and knowledge. At first glance, the strips of cedar and sailcloth seem delicate, fragile, and they have certainly been treated that way in the past. The reality is that they are durable and represent the strength of the people involved in the transaction. The materials are tough and much more resilient than the paper on which they are written. The cedar has not crumbled.

In January 2016 the Huu-ay-aht bought back Rance Island. As Huu-ay-aht elected Chief Councillor Robert Dennis Sr.said, they paid much more to get it back than they did in 1859.8.Cindy E. Harnett, “Huu-ay-aht land deal gives new life to Bamfield,” Times Colonist, January 22, 2016, https://www.timescolonist.com/news/local/huu-ay-aht-land-deal-gives-new-life-to-bamfield-1.2156655 (accessed October 22, 2019). But like the cedar strip, the Huu-ay-aht are resilient.

CASE STUDY: Christmas cards from LeJac

- Christmas cards from LeJac Residential School, photograph courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

- Christmas cards from LeJac Residential School, photograph courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

The archives hold records relating to residential and day schools. These records are part of various collections: the library collection, records of religious organizations, records of teachers and individuals that worked at schools. On a sunny day in July, I am processing newly acquired records. I open a box for the first time. In it is a file labelled “Lejac school, 1970s.” The folder is thick, filled with cardboard pages. On each page is a Christmas card. The cards depict Christmas scenes that are at once familiar and new, unusual. The silk-screened images are colourful and fuse Indigenous imagery with traditionally European Christmas scenes. (I use the term Indigenous broadly here, as with research I discover that the artists, cut off from their home communities and artistic practices, were encouraged to paint in whatever tradition they felt comfortable. This often meant Indigenous styles that they learned from textbooks, blending a multiplicity of regional forms.) In some cases a greeting in the artist’s language is included. In some cases, the greeting replaces an image. Each card includes a small square stamp, custom made for the artist, listing their name, grade, and their home community.

The cards were made by students of Lejac Residential School, located in northern BC near the town of Smithers. Made in the 70s, the students, if still alive, would now be in their 50s.

I instantly think of the children. I come back to admire the cards for their artistic qualities later, but first I imagine each of these children one by one: Vern age 13, Margie age 13, Donna age 13, Ida age 10, Patrick age 10 , Kenny age 13, and many more.9.I have not included the surnames of the students as I am in the process of contacting and consulting with the artists or their family members regarding the future of these records. Were they lonely? Hurt? Angry? Hungry? Did creating these images help them to feel connected to the families from which they had been separated, likely forcibly? Or did it enhance the pain of loneliness and in some cases abuse?

The fact that I have come to think of the records as their creators embodied indicates that I have taken in what Linda and Marilyn told me during the cedar brushing ceremony: I am working with people, not paper, not documents, not art. These items are parts of those people, and in handling them I am honouring those people. These records are particularly special as they were created by the students themselves (as opposed to records that are created about students by others), and incredibly we can identify most of the artists. The next step is to contact the artists or their family members to consult with them about the work.

With all the records relating to Residential Schools, the archives is committed to consultation with Indigenous stakeholders. In many cases, this means meeting with band councils, survivor support groups, and local Indigenous historical or cultural societies. This consultation can be painful but is crucial: we must ensure that the work we do going forward does not cause undue harm by providing access to sensitive material, or making information public before alerting the people connected to the records. This is the aspect of the work for which I am most grateful: the chance to connect with people. Seeing the impact of processing these records and bringing this truth forward is the most rewarding part of the job.

This journey of learning

I am privileged to work at a job that brings me in contact with items of beauty and importance, and the even greater privilege of getting to meet with people whose lives are touched by these items. I feel lucky to be working in this profession at a time of significant change in the way we approach Indigenous records, but I am aware that this is the beginning of a long transformation. I expect this journey of learning to last throughout my career and my lifetime. With that in mind, I ask myself: How can I ensure that I do not become complacent? How do I continue to put people first, and always remember that each record is intrinsically connected to a human? For now, I remain grateful to have the honour of doing this work, and that sense of thankfulness keeps me dedicated to listening, learning, and doing the work well.

References

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015).

Paulette Regan, Unsettling the Settler Within: Indian Residential Schools, Truth Telling, and Reconciliation in Canada, (UBC Press 2010), 12.

Further Reading

Allen, Summer. “The Science of Gratitude: A white paper prepared for the John Templeton Foundation.” The Greater Good Science Center: UC Berkeley, May 1018.

Bak, Greg, Tolly Bradford, Jessie Loyer, and Elizabeth Walker. “Four Views on Archival Decolonization Inspired by the TRC’s Calls to Action.” Fonds d’Archives 1 (2017): 1–21.

Baker, Martha. (2011) It’s Good to be Grateful: Gratitude Interventions at Work (Master’s thesis, East Carolina University, USA).

Caswell, Michelle and Marika Cifor. “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives.” Archivaria 81 (Spring 2016): 23–43.

Delva, Melanie. “Small, Cold Hands: The Dangers of Excising Self from Service.” Presentation made at the Association of Canadian Archivists annual conference, Montreal QC, 2016.

First Archivist Circle. Protocols for Native American Archival Materials. Flagstaff: University of Northern Arizona Libraries, 2007. www2.nau.edu/libnap-p.

Hughes-Watkins, Lae’l (2018) “Moving Toward a Reparative Archive: A Roadmap for a Holistic Approach to Disrupting Homogenous Histories in Academic Repositories and Creating Inclusive Spaces for Marginalized Voices,” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 5 , Article 6.

Jubelin, Narelle, Osmond Kantilla, Kay Lawrence, and John Pule. “Fabrics of Change: Trading Identities.” New South Wales: Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, April 2004.

McRanor, Shauna. “Maintaining the Reliability of Aboriginal Oral Records and Their Material Manifestations: Implications for Archival Practice.” Archivaria 43 (Spring 1997): 64–88.

Mills, Allison. “Learning to Listen: Archival Sound Recordings and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property.” Archivaria 83 (Spring 2017): 109–24.

Regan, Paulette. Unsettling the Settler Within: Indian Residential Schools, Truth Telling, and Reconciliation in Canada. UBC Press 2010.

Rossiter, David A. “Lessons in possession: colonial resource geographies in practice on Vancouver Island, 1859-1865.” Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007): 770-790.

Sloan, Katie; Vanderfluit, Jennifer; and Douglas, Jennifer (2019) “Not ‘Just My Problem to Handle’: Emerging Themes on Secondary Trauma and Archivists,” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 6, Article 20.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015.

Vallance, Neil. “Sharing the Land: The Formation of the Vancouver Island (or ‘Douglas’) Treaties of 1850-1854 in Historical, Legal and Comparative Context”. PhD diss. University of Victoria, 2015.

Author

Genevieve Weber is an archivist with the BC Archives. She lives and works on the traditional territories of the Lekwungen and W̱SÁNEĆ people. As the Indigenous liaison for the Archives, she has the privilege of working with people from all over the province, both in the reference room and in their communities. She is currently processing a new acquisition of records relating to Residential Schools in BC.

Genevieve Weber is an archivist with the BC Archives. She lives and works on the traditional territories of the Lekwungen and W̱SÁNEĆ people. As the Indigenous liaison for the Archives, she has the privilege of working with people from all over the province, both in the reference room and in their communities. She is currently processing a new acquisition of records relating to Residential Schools in BC.

References

| ↑1 | For examples see: Greg Bak, Tolly Bradford, Jessie Loyer, and Elizabeth Walker, “Four Views on Archival Decolonization Inspired by the TRC’s Calls to Action,” Fonds d’Archives 1 (2017); Steering Committee on Canada’s Archives: Response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Task Force, “Report on the Results from the Survey on Reconciliation Action & Awareness in Canadian Archives (2017),” Steering Committee on Canada’s Archives: Response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Task Force (May 2018); Genevieve Weber, “From Documents to People: Working Towards Indigenizing the BC Archives,” BC Studies no. 199 (Autumn 2018). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jessie Loyer in Bak et. al. “Four Views on Archival Decolonization,” 17 |

| ↑3 | For a personal reflection on the effects of working with records of trauma I recommend Melanie Delva’s account titled “Small, Cold Hands: The Dangers of Excising Self from Service” from her presentation made at the Association of Canadian Archivists annual conference, Montreal QC, 2016. |

| ↑4 | An initial study looking into cases of secondary trauma has been published and further studies on Conceptualizing Recordkeeping as Grief Work is underway. For the study on secondary trauma, see: Katie Sloan, Jennifer Vanderfluit, and Jennifer Douglas, “Not ‘Just My Problem to Handle’: Emerging Themes on Secondary Trauma and Archivists,” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 6, Article 20 (2019). |

| ↑5 | I rely heavily on the work of Marika Cifor and Michell Caswell in their paper “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives,” Archivaria 81 (Spring 2016): 23–43. For an examination of how we have applied these principles at the BC Archives, see Genevieve Weber, “From Documents to People: Working Towards Indigenizing the BC Archives,” BC Studies no. 199 (Autumn 2018 |

| ↑6 | Banfield to Colonial Secretary V.I., Ohiat, 4 March 1860, BC Archives: Colonial Correspondence GR-1372. |

| ↑7 | There are many examples of agreements between the Huu-ay-aht Nation and companies, such as forestry companies, with the cedar-wax seals. To read more about the Royal BC Museum transfer of cultural treasures and to see video footage of the seal being added to the final documentation, go to the Royal BC Museum website. |

| ↑8 | Cindy E. Harnett, “Huu-ay-aht land deal gives new life to Bamfield,” Times Colonist, January 22, 2016, https://www.timescolonist.com/news/local/huu-ay-aht-land-deal-gives-new-life-to-bamfield-1.2156655 (accessed October 22, 2019). |

| ↑9 | I have not included the surnames of the students as I am in the process of contacting and consulting with the artists or their family members regarding the future of these records. |