Lengths of rivercane shoot up like sparklers in the lap of legendary basket maker Eva Wolfe. Watching the process, one wonders how a weaver kept track of so many lengths of cane, each having its proper place in the pattern. Courtesy of Museum of the Cherokee Indian

Anna Fariello introduces a history of Cherokee fibre, featuring the remarkable doubleweave basket.

(“The old baskets are beautiful. The women were distinguished. The designs had meaning and a name. Each basket design had a name.” Spoken in Cherokee by Language Program Instructor Tom Belt.)

A preservationist at heart, I became interested in documenting Cherokee traditions when I noticed that so many tradition bearers and first language speakers were passing. I knew from my research that there was some documentation about their work and lives but, mostly, it remained buried in various archives. I hope that my writing and exhibitions are bringing their stories to light.

By the time the first Europeans landed on American shores, the Appalachian region was a deep forest. Cherokee people cultivated land along rich river bottoms, growing food for their families and hunting wild game. They gathered native plants for food, medicine, and for making things they needed. Their territory once extended to portions of eight modern US states. When the first European explorers ventured into Cherokee territory, they were amazed—and somewhat dismayed—to encounter impenetrable stands of tall willowy plants that lined the banks of the region’s rivers and streams. That plant was rivercane, used by indigenous people to weave baskets.

The Cherokee make two types of rivercane baskets: singleweave and doubleweave. The method of weaving either type begins in the same way. In a singleweave basket, the maker begins at the base and weaves upward to the rim. Like fabric weaving, the weave structure of a basket has a warp and a weft. In basketry, the warp is stationary and sometimes rigid. The weft splints—sometimes called weavers—are active and move over and under the warp. In beginning a basket, the base starts out as a square. As the weaving continues upward, the basket shape becomes round, terminating at a circular rim. A white oak or hickory hoop is added to the rim to serve as reinforcement, significantly strengthening the upper edge basket.

Doubleweave baskets (top and right) are actually two baskets in one. The singleweave basket (lower left) made by award winning Cherokee weaver Lucille Lossiah is finished off with a white oak or hickory hoop. The doubleweave (right) was made by master basket weaver Rowena Bradley. Courtesy of Mountain Heritage Center, Western Carolina University.

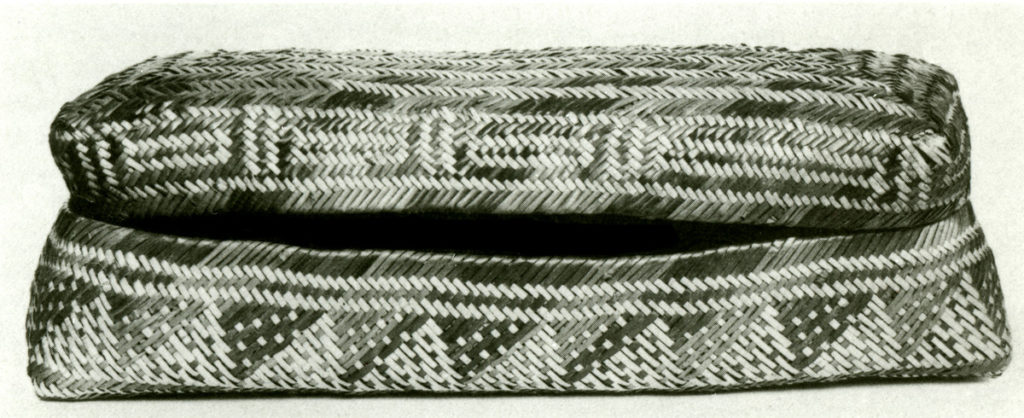

A doubleweave is actually two baskets, one woven inside the other. To make this distinctive item, a basket is begun at its base and woven upward to its rim. There, the cane is turned downward, and the basket weaver works on the outside of the basket, from rim to base. Woven in one continuous weave, the inside and outside surfaces are constructed independently of each other. The beauty and complexity of the process led the eighteenth-century English explorer John Adair to call them the “handsomest baskets I ever saw.” The inside and outside patterns of a doubleweave basket can be different, a trait that sometimes confounds the viewer. Cherokee students in the 1950s and 1960s attempted to learn the complex technique and remained amazed at its structure. One student wrote that the “unusual and intricate” weave required a person with “magic in their fingertips.”

Like all craft makers, the Cherokee depend on a reliable supply of materials in order to produce their work. But unlike the majority of today’s professional artisans, Cherokee artisans do not call on supply houses to order materials delivered—via UPS—to their doors; instead, they turn to their own environment as an essential material source. While the ancestral home of the Cherokee was once an unspoiled forested landscape, by the end of the eighteenth century, the natural habitat was diminishing. Stands of cane were cleared to make room for farming. In today’s western North Carolina mountains, vacation home construction continues to destroy native canebrakes along the rivers’ edge. A severe decline in the availability of rivercane means that basket makers must travel farther and farther to find a suitable source. As early as the mid-twentieth century, master basket weaver Eva Wolfe regularly drove 80 miles to gather cane—from her home on the Qualla Boundary to Hayesville, North Carolina.

Preparing the cane for a basket involves multiple steps—cutting, splitting, peeling/stripping, trimming, and dyeing. All of these steps must be completed before weaving can begin. The process of making a basket may be a matter of days or weeks, depending on the pace of the maker and the assistance that she may have. While family members help gather and prepare materials, the actual weaving of a basket is traditionally in the hands of women. The basket weaver trims the cane to produce long, thin, even strips used for weaving. The edges of these are razor sharp; trimming the cane is not an easy task. Eva Wolfe used a bush knife for cutting and prepping the cane and, to protect her hands, padded the knife handle with tape.

Before weaving a basket, its maker must first dye the weaving materials, unless of course she is making a basket without any added color. Harvesting and preparing native roots and bark is a separate process that requires an extensive knowledge of plants and their habitats. In the hands of Cherokee basket weavers, four plants—black walnut, bloodroot, yellowroot, and butternut—provide endless variation. They are used in different combinations and on different materials to form baskets of differing shapes and sizes. On a finished basket, this natural color palette is a characteristic that makes their baskets stand out as authentically Cherokee.

Unknown artist, likely 18th century Cherokee. This set of large baskets, in the collection of the British Museum, was brought from the Carolinas to London in 1725. It was the model for a 20th-century revitalization of the doubleweave technique. Courtesy of Frank H. McClung Museum, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

It was a lidded rivercane basket that played a major role in a twentieth-century revitalization of the doubleweave tradition on the Cherokee’s Qualla Boundary. A pair of rivercane baskets, brought from the Carolinas to London in 1725, was photographed as a single basket with lid and base, although the two pieces do not quite fit. Indeed, these are two baskets in the space of one. How convenient to use them as a single basket when a covered basket was needed, yet be able to take them apart when two baskets were required. Such nesting baskets indicate the basket weaver’s mastery of an economy of space. Many baskets could be stored together in the space of a single basket. Such variety allowed the basket’s user to choose a basket of just the right proportions for a particular purpose.

Eastern Band teacher Lottie Queen Stamper taught basketry for over 30 years, exposing hundreds of girls to their own Cherokee traditions. As part of her teaching, Stamper was asked to learn the doubleweave technique. She approached Rebecca Toineeta, a weaver and elder, to ask her help in making such a basket, but the relationship between the two women was short-lived. In 1940, Stamper came across a photograph of the doubleweave basket carried to London in 1725 mentioned above. Studying the photograph of these baskets, now in the collection of the British Museum, Stamper painstakingly worked out the design, taking a full two and a half days to establish the pattern. Using 500 splints, she wove her own replica of the baskets. “This, indeed, was the happiest day of my life,” she recalled. “Now it was my duty to teach it to my brightest students, and it was their happiest when they learned theirs.” Stamper’s “discovery” attracted attention and reinforced the doubleweave tradition among the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

An intimate knowledge of natural resources and an understanding of the suitability of each material characterize Cherokee basketry today, as always. But skill alone does not ensure its future. That will depend not only on the diligence of today’s artisans, but also on the availability of rivercane and dye plants. Each is necessary for the survival of this historic basketry form. Today, doubleweave basketry continues as a masterful tradition with younger artisans—and even high school students—excited to learn the technique. Cherokee doubleweave basketry, a truly authentic art form, promises a bright future in their hands.

This article is adapted from Cherokee Basketry: From the Hands of our Elders.

Further reading

M. Anna Fariello, Cherokee Basketry: From the Hands of our Elders, (Charleston: The History Press, 2009).

Rodney L. Leftwich, Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee (Cherokee: Cherokee Publications, 1970).

From the Hands of our Elders: Cherokee Traditions Western Carolina University

Author

Curator of over 30 exhibitions, Anna Fariello is author of seven books, numerous book chapters, and articles; presenter of over 150 conference papers and invited lectures; and director of over 30 federal, state, and private grants. She is a former Smithsonian Fellow and Fulbright Scholar and former Associate Professor at three state universities. At Western Carolina University, she curated a half dozen digital collections and online exhibitions. Fariello has been honored with a 2010 Brown Hudson Award from the North Carolina Folklore Society, a 2013 Guardians of Culture award from the Association of Tribal Archives and Museums, a 2016 Preservation Excellence award from the North Carolina Preservation Consortium, and a 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Southern Highland Craft Guild. She holds a B.A. in art from Rutgers University; an M.A. in Museum Studies/Art History from Virginia Commonwealth U.; and an M.F.A. from James Madison University.

Curator of over 30 exhibitions, Anna Fariello is author of seven books, numerous book chapters, and articles; presenter of over 150 conference papers and invited lectures; and director of over 30 federal, state, and private grants. She is a former Smithsonian Fellow and Fulbright Scholar and former Associate Professor at three state universities. At Western Carolina University, she curated a half dozen digital collections and online exhibitions. Fariello has been honored with a 2010 Brown Hudson Award from the North Carolina Folklore Society, a 2013 Guardians of Culture award from the Association of Tribal Archives and Museums, a 2016 Preservation Excellence award from the North Carolina Preservation Consortium, and a 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Southern Highland Craft Guild. She holds a B.A. in art from Rutgers University; an M.A. in Museum Studies/Art History from Virginia Commonwealth U.; and an M.F.A. from James Madison University.

Gabe Crowe on sustainability

Cherokee basket-maker Gabe Crowe shares his concerns about the availability of river cane.

Talking about that double weave in particular, it took me a week and a half to make it, but the material prep is what took the longest. It took a month and a half to work up my river cane to be able to sit down and weave that from start to finish because that style of double weave is what we call the “piece in method” where we piece in the colors to get the designs in it

It’s getting harder and harder to find river cane. There is about 3-4% left in the world cuz of people cutting it down not knowing what it is, also with people wanting river side property so they will cut it down. And infrastructure as well plays a part. There is some here in Cherokee, but it’s not big enough yet for us to use for baskets. So we have to travel further and further out to gather river cane

There has been people that has been growing river cane for us to harvest but it takes anywhere from 10-30 years to get a big healthy patch.

You can get a good size one in 10-15 years but to have one you can gather from multiple times thru out the years you need it to be there for 20 years for sure.

I think something we could use out here is something like that funded by grants to start rivercane patches here. I think Cherokee could use about six patches here on the boundary that are huge if we had that it would almost secure that our basketry wouldn’t die off.

Comments

I have a very large double weave basket that I believe. To be Cherokee but I have no proof of that. Is there some way I could send a picture? And you could tell me for sure. Question mark

I have a beautiful aging basket from Cherokee in the 1940s or earlier. I would love to send a photo. It needs conserving, perhaps. It is likely a very utilitarian basket. Possibly made for the 1940s tourist trade. It was beautiful and maintains its calming spirit. Are there native museums who would be interested in such pieces? Or a way to preserve it for the future?

Sincerely,

Lucy David